PAKISTAN

Media Martial Law

A rally to mark International Women’s Day takes place in Karachi on March 8, 2022. Credit: Asif Hassan / AFP

Even though Pakistan in 2021 became the first country in Asia to legislate for guarantees of protections from harm for journalists and other media practitioners, and a court decriminalised defamation, turmoil and tension characterised the overall state of the media industry in the period under review. A toughening up of censorship regulations and continued intimidation of journalists amounted to a case of one step forward, two steps back in terms of the health of the media industry.

However, the change of regime in Pakistan will have significant impact on the media. The new government led by Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif sworn in on April 11, 2022, is more sympathetic to the media and has decided to do away with some of the media restrictions imposed by the out-voted Imran Khan government.

This will be no mean task, given the Imran Khan government’s legacy of browbeating the media and undermining its viability by starving it of public sector advertising, a move that saw nearly two-fifths of media jobs wiped out in the preceding year. In the summer of 2021, the government first tried to push for a merger of regulators for print, broadcast and internet media. The media and journalists’ rights bodies rallied together with opposition political parties, civil society and rights groups to thwart the proposal to establish the ‘Pakistan Media Development Authority’ (PMDA), terming it an attempt to create a new ‘headquarter of censorship.’ Among other things, the PMDA proposed banning criticism of government office holders, establishing a media trial court to punish defamation and penalise erring journalists with steep fines and jail terms.

Pakistan’s new Information Minister, Marriyum Aurangzeb, has ruled out the setting up the PMDA. She told media that there is no need for any other regulatory body in addition to the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (PEMRA). A joint action committee, formed in the backdrop of PMDA and comprising all the stakeholders, would now work out a solution acceptable to all stakeholders.

In early 2022, the government had amended and made more stringent the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act (PECA) by criminalising defamation of authorities. However, within weeks, in early April, in a welcome move, the Islamabad High Court in response to a petition filed by the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ) voided the amendment.

Measures to curb free expression by the previous government were taken in the backdrop of continued physical, online and legal intimidation of journalists with several murdered or physically assaulted and many more booked in legal cases, often by government functionaries, for alleged online defamation even if they were private opinions of journalists on social media rather than relating to their formal journalism work for their employers. A clear picture emerges – over the course of the period under review – where the state seems to have solidified its role as the largest threat actor against media practitioners and increasingly resorting to intimidate journalists procedurally through legal cases to entangle them in lengthy defence in quasi trials.

On top of this, a majority of journalists suffered a prolonged run of misery in the shape of pay cuts, lengthening salary arrears and overall deterioration in working conditions in most media houses. Journalists in the periphery have been particularly hard hit, with jobs either disappearing or downgraded. Women media workers have also been facing increasing online harassment with even senior government officials joining the intimidation by especially targeting some of the most prominent women journalists.

However, after the Imran Khan government lost power following a vote of no-confidence in the National Assembly, the incoming coalition government made a pledge to undo all the anti-media measures of Khan, some of which have already been rolled out.

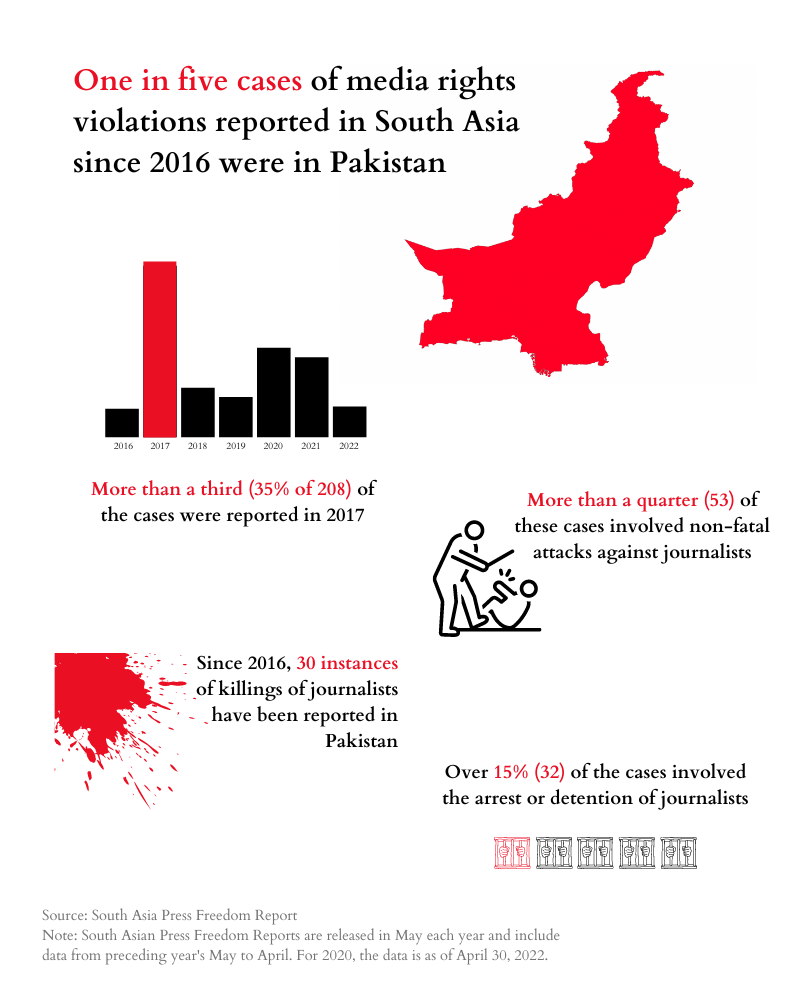

Media Rights Violations

Killings

Arrests

A resident stands beside a picture of Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan as he looks at the morning newspapers displayed for sale at a roadside stall in Islamabad on April 4, 2022, a day after Khan foiled an attempt to boot him from office by getting the president to dissolve the national assembly. Khan was later ousted from government on April 10, 2022. Credit: Aamir Qureshi / AFP

Annus horribilis

The period under review amounted to a terrible year for the state of health of the media industry, witnessing a consistent policy of curbing media’s ability to perform its duties professionally, increasing attacks on journalists and attempts to expand official coercion to online spaces. Significantly, the year was also characterised by fierce resistance from media and civil society.

The signature media obsession of the now-defunct Khan government was an attempt to legislate into existence the PMDA that proposed to dispense with all existing media-related laws and conduct centralised licensing of media and coercive regulation of content produced by all types of media: print, television, radio, digital and social media – and even cinema and publication of books. It proposed a ‘media court’ to try journalists and content producers for violations and impose jail terms and steep fines for those convicted.

The proposal was, however, successfully thwarted through concerted civic action after journalists and other media practitioners were joined in their resistance by civil society, rights groups and political parties from across the country. The opposition parties called PMDA “media martial law” and the PFUJ christened it the “new headquarters of censorship.” International media watchdogs also denounced PMDA saying it would severely undermine freedom of expression and independent journalism by serving as a ‘one window operation’ to control public interest narratives. Thanks to resistance spearheaded by PFUJ and its allies, both the standing committees of National Assembly and the Senate, managed to prevent the PMDA bill from being tabled and converted into a law.

In October 2021, the technology and telecom ministry issued the “Removal and Blocking of Unlawful Online Content” regulations giving authorities the right to control and censor any type of message posted on social media platforms. The regulations were promptly challenged, including by PFUJ, in the Islamabad High Court. The court, which had been seized with a case involving the highhandedness of authorities in filing cases against journalists for their critical online opinions, managed to thwart the process. In early 2022, the government had unilaterally amended the PECA law to criminalise dissent online and raising punishment of criticism of officials and government institutions to five years. A fierce challenge was mounted. The PFUJ challenged the amendment in the Islamabad High Court where it was declared unconstitutional and voided on April 8, 2022.

Not surprisingly, Prime Minister Imran Khan has been named one of the worst international leaders for censoring and intimidating journalists who dare not to toe the government’s line. Amnesty International had said Pakistani media was facing a “structural attack” by authorities including “applying pressure on independent media houses, their advertisers, their owners and individual journalists to toe the line and not hold power to account. Dissent is being consistently treated like a crime.”

A report released by the Council of Pakistan Newspaper Editors (CPNE) in February 2022 said the working conditions for journalists worsened in 2021. It expressed concern over increasing attempts to stifle the media and negate the right of access to information.

A survey conducted by Digital Rights Foundation (DRF) in November 2021 said 78 per cent journalists in Pakistan complained of facing harassment, personal attacks and threats of physical violence on online platforms and social media while fulfilling their professional duties.

UNESCO in November 2021 expressed concern at a public event in Islamabad at the growing incidents of attacks against the media in Pakistan, in particular the increasing intimidation of women media practitioners, including in online spaces. Officials at the event admitted the government had no mechanism in place to monitor attacks against the media and therefore no reliable data of its own to determine the scope of the problem.

A study conducted by the Centre for Excellence in Journalism at the Institute of Business Administration (IBA) Karachi found that over 50 per cent of working journalists in Pakistan’s largest city are suffering stress, anxiety, depression or other forms of mental health issues relating to their working conditions.

In a legal pushback, IFJ Secretary Anthony Bellanger and Secretary General PFUJ Rana Muhammad Azeem filed a petition before the Islamabad High Court raising issues of working conditions and safety. The IFJ had written a letter to the Chief Justice of Islamabad High Court highlighting problems and unlawful actions being faced by the media in Pakistan while Rana Azeem also wrote a letter to the Court to highlight problems like illegal terminations, irregular salaries, safety issues etc. The court has converted these letters into petitions. The Court has sought reports from FIA, Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (PEMRA) and the Information Ministry. The court has already given direction to appoint judge for the ITNE. The final hearing was scheduled for May.

New laws on safety

Pakistani media practitioners faced several safety related challenges in the period under review. These included a continuing spate of physical attacks that resulted in the murder of five journalists, including a citizen journalist; assault on and injuries sustained by at least six journalists; arrest or abduction of at least seven journalists; legal cases or notices faced by at least 15 journalists; attacks or intimidation of at least five media establishments; specific threats against journalists in at least four instances; and several instances of coordinated or violent online harassment and intimidation of journalists and other digital information practitioners, including women.

About the only bright spot for media in Pakistan in the period under review was the passage of two laws on safety of journalists, first by Sindh province in July 2021 and then by the federal government in December 2021. The two laws commit the state to combat impunity of crimes against journalists. The laws are significant because throughout this century Pakistan has found itself on global indices as one of the worst places on the planet to practice journalism. Over 140 journalists, including two women, have been killed in the line of duty since 2000, according to national media advocacy organisation Freedom Network. These two laws, however, still haven’t been operationalised in the period under review. But once operationalised they should theoretically reduce the endemic levels of violence against media practitioners.

There are two key shortcomings in the laws, though. The first is that the federal law seems to contradict its own mandate of protection for journalists through its Clause 6 that prequalifies beneficiaries only after proving that any threats they faced resulted from ‘good faith journalism.’ Inability to prove that will offer no protection under the law. This renders the law unhelpful and will have to be amended to make protection unconditional. In early 2022, the government appeared willing to amend the law to make protections unconditional. The second is that Pakistan’s other three provinces have been slow in developing their own versions of bills on safety of journalists. In December 2021, political parties in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa unanimously passed a resolution calling for special legislation on journalists’ for media practitioners of the province.

In January 2021, the PFUJ gave the government a three-month ultimatum to take effective steps for resolving the acute problems of journalists and media issues and reverse “the worst ever suppression of the right to free press and expression that has severely compromised the independence of media in the country.”

A man reads a newspaper featuring coverage of the Russian invasion of Ukraine at a stall in Karachi on February 25, 2022. Credit: Asif Hassan / AFP

Spotlight on impunity

In December 2021, a report by the Committee to Protect Journalists ranked Pakistan ninth out of 12 countries where journalists have been killed and the perpetrators are still at large.

In May 2021, The European Union issued a statement over the spate of violence against journalists in Pakistan expressing concerns about “widespread and systematic harassment online, especially of female journalists, through coordinated campaigns that include abusive language and threats of violence.”

In August 2021, over 100 Harvard-educated journalists from round the world issued a joint statement on behalf of the Neiman Foundation expressing concerns over a surge in attacks on journalists and media workers in Pakistan and urging the government to end impunity against such crimes.

In May 2021, the Freedom Network said its research of the preceding year documented a 40 per cent increase in cases of attacks and violations, the emergence of Islamabad as the most risky place in Pakistan to practice journalism, the three most frequent violations against journalists being legal cases, murder threats and arrests, with government officials being the biggest threat actor targeting journalists.

In January 2022, Human Rights Watch issued an annual report on Pakistan criticizing it for its crackdown against dissent, saying: “The authorities [have] expanded their use of draconian sedition and counterterrorism laws to stifle dissent, and strictly regulated civil society groups critical of government actions or policies.”

A report released by the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) in March 2022 noted with concern that journalists and editors in Pakistan were being compelled to work at even greater personal risk than before. It added that media remains hostage to repressive tactics and documents how women journalists especially are experiencing increased threats and harassment in the line of duty. It also accounts for the media landscape in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa provinces where threats to journalists and media blackouts have severely compromised the public’s access to information.

Women push back

Less than five per cent of journalists in Pakistan are women, as per estimates of the PFUJ. Even in the best of circumstances they continue facing not only physical and digital security threats but also additional intimidation. This includes online harassment, sexual innuendos and organised abuse.

Trolling of female journalists as a specific target of media intimidation began in 2020 by supporters of Imran Khan’s party, continued in 2021-22. The ongoing attacks resulted in over 100 women journalists writing an open letter to the prime minister seeking him to intervene and put a stop to it.

In late 2021 this was taken to a whole new level when federal ministers and special assistant of Khan’s cabinet joined hundreds of thousands of ruling Pakistan Tehrik Insaf (PTI) activists on Twitter to hound award-winning journalist Asma Shirazi for an article she wrote in BBC. “Asma, better you join (opposition party),” Commerce Minister Hammad Azhar tweeted. Special Assistant to PM Shahbaz Gill addressed a press conference slamming Shirazi for being “unethical” without spelling out how. Human Rights Minister Shireen Mazari while taking on the journalist in her tweet even referred to BBC Urdu as “Bharat (Indian) Broadcasting Corporation” and implying Shirazi was an Indian agent. In February 2022, television current affairs show host Gharida Farooqi was similarly the target of organised trolling by supporters of PTI for commenting her show guests made about a minister awarded as the best cabinet performer by Khan.

In August 2021, the Digital Media Alliance of Pakistan (DigiMAP) issued a statement to express solidarity with women journalists in the country being attacked online for their journalism and expression. “Despite a hearing of the National Assembly Standing Committee on Human Rights where women journalists provided testimony of the online attacks they faced, the digital abuse and trolling of women journalists has continued unabated,” said the statement.

In November 2021, IFJ conducted a training on gender equality and workplace safety for women members of the Karachi Press Club and all factions of Karachi Union of Journalists (KUJ). The training focused on breaking the glass ceiling, securing salary increases and promotions, ending workplace harassment and empowering unions and media organizations to include women in decision-making.

The government in Pakistan attempted to accelerate its long-running efforts to beef up internet controls with the intended consequence of expanding its policy of reduced tolerance for dissent in the online realm.

A supporter of the Pakistan Muslim League-N (PML-N) holds a party flag with images of Shehbaz Sharif and his elder brother and former prime minister Nawaz Sharif outside the parliament house building in Islamabad on April 11, 2022. Pakistan lawmakers elected Shehbaz Sharif as the country’s new prime minister following the ousting of Imran Khan. Credit: Aamir Qureshi / AFP

Transforming unions

Two principal challenges of defending rights of media practitioners defined the changing media environment in Pakistan in the period under review: (1) Diversity and inclusivity in representation: Journalists’ unions and media workers’ associations are struggling to reform representation concepts and practices, hampering functional transition for a new age of media and defending rights of its workers; and (2) Solidarity through modernisation: Resistance against increasing curbs on free speech and access to information without reforms and modernisation of organisational structures of media unions are resulting in poor solidarity, non-representative strategies, and inadequate results on protecting workers rights and working conditions.

In late 2021, the IFJ in partnership with Freedom Network produced a report titled Modernization and Reforms: Towards Representative Models of Journalists’ Unions, Associations and Press Clubs in Pakistan that outlined challenges and solutions of promoting labour rights, gender equality and freedom of association in Pakistan’s shifting media landscape. This baseline research was part of a rapid assessment of key factors preventing media unions in Pakistan accepting the growing number of young journalists, particularly digital and women practitioners, as members and defending their labour rights. Key findings of the report included the following:

- The current charters and constitutions of unions have become obsolete with an increasing number of journalists switching to digital journalism, freelancing and becoming younger with more women practicing digital journalism – but these new realities are not adequately reflected within the representative platforms.

- There is an absence of urgency or dialogue between legacy media (print and electronic media) and digital media (internet media) practitioners on addressing the issue.

- The criteria of membership of unions have become self-defeating by disenfranchising eligibility of current members and ineligibility of new members.

- There is a lack of affirmative action on encouraging diversity in representation among office bearers of journalists’ unions.

- There is an existing constituency of groups of young, women and digital journalists without effective advocacy and communications skills to lobby for their cause for better representation within unions and workers.

- Hurtful but preventable factionalism within unions is preventing consensus on reforming charters and policies, and strategies to upgrade the struggle for rights of working journalists and media workers across the entire spectrum of the evolving media landscape.

Tightening the legal noose

The legal environment decidedly worsened for media practitioners in Pakistan in the period under review. In February 2022, the government amended the cybercrimes law, PECA, criminalising defamation of authorities, including key government functionaries, the military and judiciary, making the offence non-bailable with five years in jail upon conviction. But in a welcome move, after the amendment was challenged in court the whole ordinance amending PECA was declared ultra vires of the constitution and annulled for being in contravention of the constitutional articles 19 (freedom of expression) and 19-A (right to information).

Additionally, Section 20 of the original PECA law of 2016, which dealt with criminalization of defamation, was also declared ultra vires of the constitution, and ordered amended. A key problem with the 2022 amendment was the mandate given to FIA to be the principal executor of the amended part of PECA. This was problematic because FIA can take cognisance of a case only when referred to it by federal authorities while the amendment allows it suo moto powers to become a referee to itself on defamation cases. This meant no complaint need be made against a journalist – a bureaucrat who is not even personally aggrieved would have been empowered to be both a complainant and investigator. This allowed FIA the powers of adjudication, thereby allowing it to be both jury and judge. This, however, not stands infructuous after the court verdict in April 2022.

Even before the amendment, the PECA law was increasingly being misused as a legal tool against journalists and critics. A report released by the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) in February 2022 said the stated aim of PECA stems from a security state narrative drawing cover from the National Action Plan whose purported agenda was first to curb terrorism and hate speech online and second to save women from harassment. It said it failed on both counts because PECA is “a political problem wedged in a criminal justice system.”

In September 2021, the FIA told the IHC nearly 150,000 complaints under PECA were registered with it between mid-2019 and mid-2021 of which less than 250 were decided. It admitted its gross incapacity to deal with the PECA workload, including, “inadequate staff, training and need for upgradation of the forensic labs…. The number of trained officials / investigators is not adequate to effectively deal with the huge spike of cyber-related offences.” In February 2022, the IHC intervened and stopped authorities from making any arrests under the amended law. The amendment was rejected by stakeholders, on the back of a Joint Action Committee (JAC) of media stakeholders, comprising representatives of media organisations PFUJ, All Pakistan Newspapers Society (APNS), Council of Pakistan Newspapers Editors (CPNE), Pakistan Broadcasters Association (PBA) and Association of Electronic Media Editors and News Directors (AEMEND).

In September 2021, the Digital Media Alliance of Pakistan (DigiMAP) and Freedom Network produced a briefing paper on the likely impact of the proposed PMDA bill, warning that the proposed single centralised media regulator would adversely impact digital media, socio-political narratives and public interest journalism in Pakistan. It pointed out that one of the most affected sub-sectors is expected to be the digital public interest news media posing “a serious threat to the emerging ecosystem of independent public interest digital journalism.”

PECA pressure

The chilling pattern that emerged in the preceding year in the use of the criminal defamation section of Pakistan’s PECA law, being used frequently to charge journalists and information practitioners in connection with their digital journalism and online expression, continued. There has been a corresponding increase in the efforts to control online expression, either legally or through coordinated digital campaigns against journalists, continued. A report titled Criminalizing Online Dissent through Legal Victimization: Impunity against Journalists Prosecuted under PECA, issued in November 2021 by Freedom Network, supplies evidence that PECA has emerged as the primary legal instrument to intimidate and silence Pakistani journalists in recent years because it criminalises online expression. It revealed that cases were registered against 56 per cent of the two dozen Pakistani journalists and information practitioners who had a brush with PECA between 2019 and 2021. Of those formally charged, around 70 per cent were arrested while over half of those arrested were tortured in custody.

Another key finding was that two-thirds of the complainants invoking the PECA law against journalists are private citizens with the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) officials the second highest initiator of complaints; Opinions or criticism of the military and the intelligence agencies is the most frequent complaint against journalists; Staff journalists and freelancers are equally likely to be targeted under PECA; over a third of the freelancers targeted under PECA operate their own YouTube channels; Over half of the journalists targeted under PECA work for digital media platforms; Section 20, which criminalises online defamation and carries a three-year jail term and up to one million rupees (approx. USD 5000) in fines, is the most frequently invoked section against journalists; Only a third of the complaints registered against journalists resulted in inquiries completed in due time; Criminal cases were registered against nearly two-thirds of all journalists pursued under PECA; For nearly all journalists charged, clauses and sections from additional laws were also invoked against them. After the original PECA law was ordered amended by the Islamabad High Court in April 2022, it is expected that the worst abuses by the bureaucracy against journalists might come to an end in subsequent months.

Pakistan is on a steep and slippery slope on the media landscape with the Imran Khan government want only eroding freedom of expression through coercive internet regulations, cutting off lifeline public advertising for media that has resulted in thousands of job losses and criminalising dissent.

Colleagues of Pakistani journalist Matiullah Jan protest his forced disappearance in May 2021, after the journalist was kidnapped outside a school in Islamabad. Credit: Aamir Qureshi / AFP

International obligations

Media safety laws: With over 140 journalists, including two women, killed in the line of duty since 2000, impunity levels are so high that not a single killer has been convicted and punished conclusively after exhausting the entire judicial process. This is despite the fact that Pakistan was one of the five pilot countries for implementation of the UN Plan of Action on Safety of Journalists and Issues of Impunity that, among other things, urges legal state mechanisms to combat impunity. In the period under review, Pakistan made a major stride in implementation of the UN Plan of Action in July 2021 when the Sindh province passed a landmark local law aimed at keeping journalists in its jurisdiction safe. Under Pakistani constitution, the country’s four provinces can legislate their own laws on most state subjects. This was followed by another milestone national law on safety of media practitioners by the federal government that also seeks to combat impunity of crimes against journalists.

The laws are significant because they acknowledge at the duty bearers’ level (the state) that professional journalism in Pakistan needs safety guarantees for right holders (media practitioners). They both make references to the UN Plan of Action as best practice guides on how to combat impunity. They also make special provisions for additional safety guarantees against harassment of women media workers and make progressive interpretation of who as journalists can benefit from the law.

Media labour laws: In July 2021, the IFJ in partnership with the Institute for Research Advocacy and Development (IRADA), released a special report, Decent Work in Pakistani Media: An Assessment of Labor Laws and the Impacts for Media Workers in the wake of the continuing crisis of non-payment of wages, coupled with massive job losses and widespread job insecurity within the once-thriving Pakistan media industry. The landmark assessment of Pakistan’s existing and applicable labour, industrial and worker laws sought to better understanding of the status, facts, qualities, shortcomings, and deficiencies in the legal framework relating to labour rights in Pakistan.

The report found that despite the existence of a long-established and extensive constitutional and legal framework, Pakistan’s media workers face a redundant and ineffective labour law system that is failing to protect essential worker rights and impresses a dire need to review and overhaul the legal framework governing the rights of media workers in Pakistan where it is chronically failing them. The report highlighted as problematic the non-inclusive legal framework for women and other marginalised segments such as religious minorities; Non-recognition of electronic and online/digital media platforms and the dire need to reform labour laws to align them to international best practice; Non-recognition of informal workplaces and freelance media workers, which are a fundamental part of the labour market in the media sector; A frail collective bargaining system that impacts media workers’ rights; Poor awareness of media law and its application among media workers; Inadequate measures to ensure safety of media workers and journalists; Redundant and ineffective media institutions, including wage boards and the Implementation Tribunal for Newspapers Employees (ITNE).

Collaborative pushback

A media-led coalition of civil society actors thwarted a draconian media law. After the Pakistan government proposed the enactment of a new regressive media law in 2021, several media and civil society stakeholders actively came together in an organic media-led advocacy campaign to resist the proposed law. They signed a joint statement to reject the law in August 2021.

The campaign also took out joint advertisements in print and on TV that brought together various national and international media representative association in greater solidarity. Several groups participated in a protest demonstration outside the parliament in Islamabad against the proposed law organized by PFUJ. The advocacy campaign received support from human rights CSOs and associations of lawyers as well as international groups and press freedom organisations.

The joint campaign also elicited support from opposition political parties, which promised to block the legislation in the Parliament. As a result of the sustained joint resistance, the government abandoned the proposed media law. A concerted effort by media and civil society also resulted in the abolition of the amendment to the PECA law of 2016 criminalising dissent as well as a new amendment ordered to defang Section 20 of it to decriminalise dissent.

Rebuilding trust and credibility

Public trust in media has been plummeting in Pakistan for several years now as it gets manipulated and coerced by the authorities. Through various measures including often violent intimidation of journalists, economic squeeze, coercive censorship policies and an overall closing of spaces for free speech, the media has been coerced into peddling mostly narrow state interests and compromise heavily on its mandate to be the guardian of public interest.

This trajectory must be reversed by improving upon the growing solidarity between media representative association and civil society. Considering the cross-cutting linkages between safety of journalists and an enabling environment that supports freedom of expression, which was instrumental in the passage of two journalists’ safety laws in 2021, better results on safety of media practitioners and a more conducive environment for media can be achieved by supporting calls for establishment of a broad-based civil liberties alliance.

This alliance can focus on free speech protections bringing together a broad array of stakeholders from media groups to human and digital rights campaigners, from legal community to women’s and minorities groups, from statutory and non-statutory commissions to political parties. Together they can better defend free speech and lobby for reform to laws that constrict press freedom.

In the face of increasingly precarious and deteriorating work conditions for journalists, the need to protect, uphold and advocate for the rights of all journalists is critical. Collaborative efforts need to be made to promote solidarity through strengthening the capacity, confidence and strategic networking of journalists’ representative organizations and press clubs, as well as representatives from mainstream, freelance and entrepreneurial independent digital media to devise an integrated approach to a decent work agenda to promote labour rights, gender equality and freedom of association in Pakistan’s shifting media landscape.

Pakistan is on a steep and slippery slope on the media landscape with the Imran Khan government want only eroding freedom of expression through coercive internet regulations, cutting off lifeline public advertising for media that has resulted in thousands of job losses and criminalising dissent.

PFUJ Secretary General Rana Muhammad Azeem joins a protest of senior journalists from Daily Nation & Daily Nawa-i-Waqt against non-payments of workers’ salaries and arrears at Lahore on February 6, 2022. Credit: PFUJ