Overview

A Turbulent Year

South Asia witnessed tremendous change over the past year – via transformation effected through electoral ballots, as well as feet on the ground. Student movements and everyday citizens were among those leading phenomenal pushbacks against entrenched authoritarian regimes, voting out incumbent governments and expressing unified dissatisfaction with misgovernance, corruption and overreach. Amid the upheaval, the media played a critical role in amplifying people’s aspirations and speaking truth to the powerful.

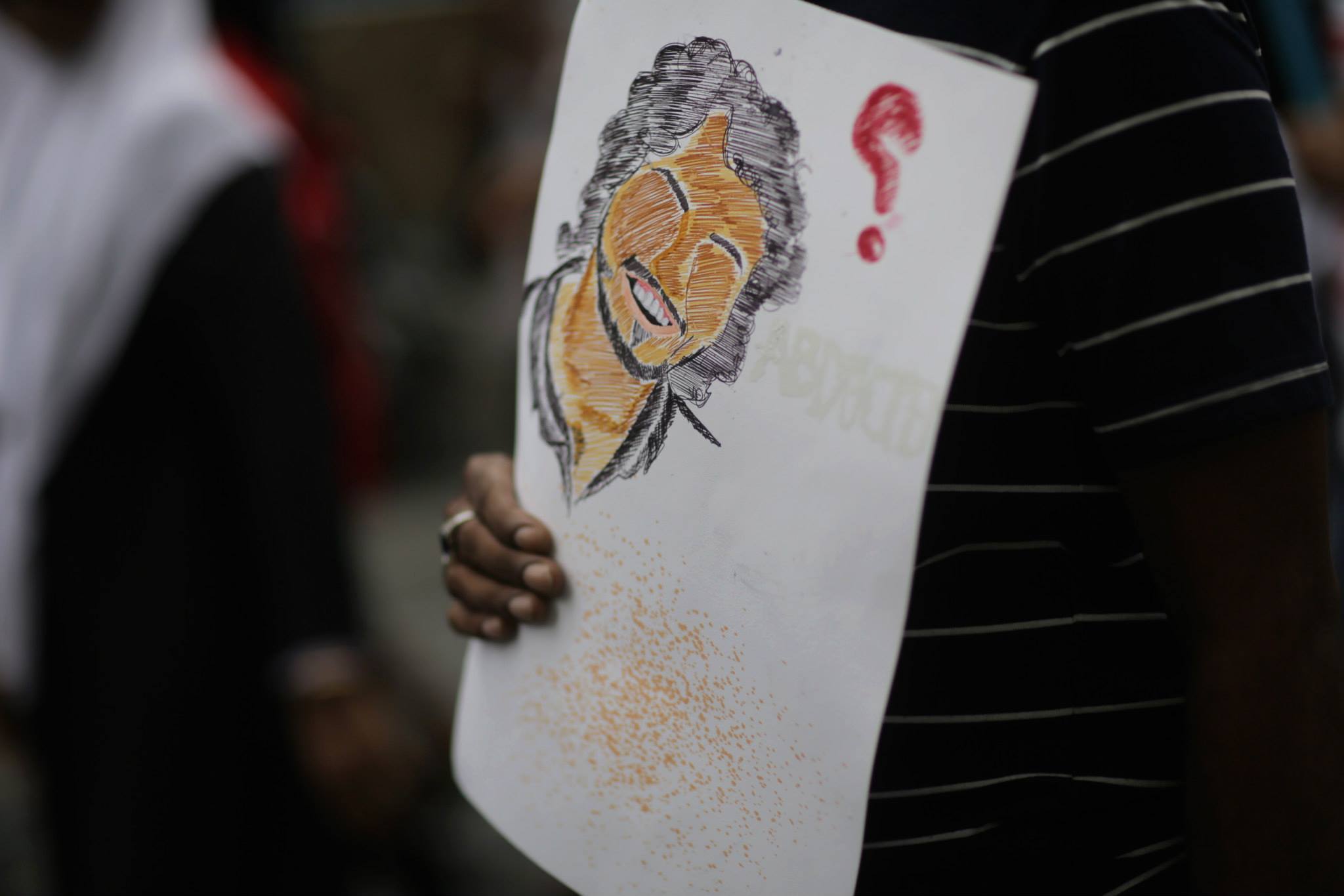

The most dramatic political landscape transformation was the ouster of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina of Bangladesh, when an immense student-led uprising brought to an end her increasingly iron fisted rule. Hopes are now pinned on the country’s new Chief Adviser Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus to help rebuild state institutions, revive the economy, restore human rights and press freedom and combat the deeply entrenched communal polarisation and a newly emboldened right-wing.

In Sri Lanka, the natural next step on from the people’s movement of 2022 came with a major political shift achieved through the ballot in the September 2024 presidential election. The victory of Anura Kumara Dissanayake, of the left of centre National People’s Power (NPP) or Jathika Jana Balawegaya, followed by the party’s definitive victory in November’s parliamentary elections signified a departure from the country’s deep-rooted dynastic rule under the Rajapaksa family, characterised by authoritarianism, corruption and economic chaos. The new president, known widely as AKD, has cast himself as a disruptor to the status quo for his anti-corruption platform and pro-poor policies in the wake of the country’s worst ever economic crisis, which is still having an impact on millions.

In Pakistan, political instability and intervention by the military apparatus in virtually every area of public space, was clearly evident during and following the national election in February 2024. Fraught with political repression and violence, the national elections were heavily tainted by allegations of rigging, voter suppression and technicalities that resulted in the deregistering of one major political party. When a post-election alliance brought to power two dynastic parties that had won fewer seats individually, the opposition Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) took to the streets in months-long, and often violent agitations that left many dead and injured. Ranked at 124, Pakistan’s democracy ranking fell by six spots in the year to be listed among the top 10 worst performers in the Democracy Index by the Economist Intelligence Unit released in February 2025. The Democratic Index now firmly terms Pakistan as no longer a democracy, but an authoritarian regime.

In Bhutan, a quiet but firm political upheaval resulted in the country decisively voting out the incumbent government and choosing to unequivocally place faith in one of the country’s oldest political parties, the 18-year-old People’s Democratic Party (PDP). The role of the media in voter literacy in a country where about half the population is under 25 years old, cannot be underestimated.

The atoll nation of the Maldives saw a peaceful transfer of power via the ballot, with the parliamentary elections of April 2024 again ushering in a government of the ruling People’s National Congress with a thumping majority. While the electorate’s message was in favour of stability, a weakened opposition has raised concerns about arming the new president, Mohamed Muizzu, with both executive and legislative control. Unchecked power has never boded well for freedom of the press, particularly in the case of the Maldives.

The Indian electorate returned the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to power with a reduced majority. But hopes that the diminished numbers would temper aggressive and non-consultative policies have not been upheld.

Instability and shifting coalition dynamics marked Nepal’s political scene in the past year. A fragmented parliament with no clear winners after the election in January 2024 ultimately led to KP Sharma Oli, forming a coalition government with the centrist Nepali Congress in July 2024. It marks his fourth tenure as the country’s prime minister. But fragile alliances and ongoing political instability in the country, including a resurgence of a pro-monarchy movement, have so far plagued attempts at legislative action, including long awaited amendments to policies and laws related to the media.

Amid the hope engendered by political change in its neighbourhood, Afghanistan’s media faced yet another year of plummeting press freedom with the country now sitting just two places from the bottom of 180 countries in the 2024 World Press Freedom Index. Hard fought achievements over recent decades on access to information, media funding and viability, as well as gender equity and plurality are now all but erased. Yet Afghan journalists continued to cling tenaciously to hope, endeavouring to operate within a media landscape of heightened restrictions, especially for women.

The most dramatic political landscape transformation was the ouster of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina of Bangladesh, when an immense student-led uprising brought to an end her increasingly iron fisted rule.

The ousting of iron-fisted Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina in Bangladesh had ripple effects across the region and strained ties with neighbouring India. Hindus make up almost ten per cent of Bangladesh’s 174 million people. After the embattled leader fled to India, the post-Hasina power vacuum also led to increased violence against members of the Hindu minority community. A vendor hangs a newspaper along a roadside in Hyderabad, India, on August 6, 2024. Credit: Noah Seelam / AFP

Unfree digiverse

Across the region, the digital space continued to offer immense opportunities to expose corruption and human rights violations and challenge mainstream and official narratives. Online editions of mainstream media, as well as individual journalists, bloggers, podcasters and YouTubers have now claimed and marked out a critical space online. The problem remains, however, with maintaining professional standards and editorial verification processes.

In Pakistan, the passage in January 2025 of the Prevention of Electronic Crimes (Amendment) Act (PECA) was met with vehement protests, hunger strikes and demonstrations across the country. Ostensibly created to combat ‘fake news’, the law has been termed “draconian” and an assault on free speech. Amended provisions to allow third-party legal entities to lodge complaints with the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA), raised concerns about suppression of dissent.

In February 2025, during her visit to Pakistan, IFJ president, Dominique Pradalie, joined union leaders in a protest march in Islamabad against the controversial amendments to the PECA Act, urging Pakistani authorities to uphold freedom of expression, and repeal the PECA Act.

India globally ranks second after China in terms of internet users, now estimated at more than 806 million individuals. With social media user penetration at 34 per cent, the elections to parliament and several state assemblies in 2024 presented an opportunity for social media to fill gaps that mainstream media seemed hesitant to cover. The massive surge in digital advertising spending testified to the role of social media marketing, with the total election budget for political parties collectively reaching INR 13,000 crore (approximately USD 1.5 billion) across various media platforms. The ruling BJP had the most prominent online presence, using social media and artificial intelligence (AI) driven tools, influencers and even paid trolls to target opponents, human rights activists and journalists. But other parties are fast catching up. These new avenues for dissent were also spaces that strongly peddled misinformation.

The Global Risks Report 2024, released by the World Economic Forum, currently ranks misinformation and disinformation as the number one risk now facing the world. Distorted and manipulated information, which has become increasingly easier with AI enabled tools, will continue to have far reaching impacts, it warns.

Reflecting the global trend, alarmingly though not unexpectedly, social media platforms in India were also used to spew hate and polarise communities. A report ‘Social Media and Hate Speech in India’ of the Centre for the Study of Organised Hate (CSOH) identified Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, YouTube, Telegram, and X (formerly Twitter) as key drivers enabling, amplifying, and mainstreaming hate speech and extremist ideologies, spreading Hindu nationalist ideology and anti-minority rhetoric.

Government overreach and control was visible in the number of takedowns of YouTube – the highest globally over the last three months of 2024, for ostensibly violating “community guidelines”. ‘Sahayog’, a portal launched in March 2025 to facilitate co-ordinated action on cybercrime, has come in for criticism by some of the major platforms. Elon Musk, owner of social media platform X has termed it a tool of censorship and refused to join the portal.

In another small pushback, on September 20, 2024, the Bombay High Court struck down the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Amendment Rules, 2023, which allowed the Central Government to form a Fact-Check Unit to identify online content regarding government business as “fake, false, or misleading”.

Internet shutdowns continue to be another way of turning off the switch on information sharing that is unpalatable to governments. According to digital rights advocacy group Access Now, for the first time since 2018, India with a total of 84 internet shutdowns in 2024 was not ranked first in internet shutdown orders, following Myanmar this year with 85 shutdowns. Shutdowns were done on various pretexts: communal conflict, protests and instability, to prevent cheating in exams, and elections, with Manipur and Kashmir facing the highest number of shutdowns.

In Pakistan’s elections there was a significant shift toward social media for campaigning, alongside traditional rallies and meetings. But the proliferation and ease of dissemination came with attendant problems of extreme polarisation, trolling and abuse. Disinformation and deepfakes muddied the waters and invited typical government responses of bans and suspensions of platforms and slowing down internet services.

During the Sri Lankan parliamentary and presidential elections in 2024, digital platforms became vehicles for misinformation and online abuse, with the Election Commission as well as tech giants standing by helplessly. Women candidates were exposed to malicious social media attacks, undermining their right to public office.

Online editions of mainstream media, as well as individual journalists, bloggers, podcasters and YouTubers have now claimed and marked out a critical space online.

Amendments to Pakistan’s Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act (PECA) were met with nationwide protests by journalists and freedom of expression activists. The PECA law presents a clear battleground for the media with the amendments effectively criminalising online disinformation. Leaders and activists of the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists protest in Karachi on January 31, 2025. Credit: Rizwan Tabassum / AFP

Is AI the future?

The rapid entry of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in newsrooms in South Asia has forced a hasty appraisal of its possibilities and challenges. ‘Media Metamorphosis: AI and Bangladeshi Newsrooms 2024’, a study conducted by the Media Resources Development Initiative (MRDI) found that, while 51 per cent of journalists have utilised AI tools, only 20 per cent of news organisations have institutionalised its use. ChatGPT was the most popular tool, accounting for 78 per cent of all usage.

While the impact of AI in Indian newsrooms has yet to be studied systematically, there is no doubt that India saw a spike in demand for services from AI content agencies, with political parties estimated to have spent over USD 50 million on AI-generated campaign material in 2024.

AI may not have taken off yet in Sri Lankan newsrooms, but in May 2024, state broadcaster Sri Lanka Rupavahini Corporation (SLRC) made history by using two AI versions of Chaminda Gunarathne and Nishadi Bandaranayake, two of SLRC’s most popular news anchors, taking a significant step in the use of AI tech in Sinhala language newscasting.

Newsrooms in Pakistan are increasingly using AI to enhance professionalism, but the impact of this transition on jobs and the media economy has yet to be systematically studied. The first country in South Asia to introduce a policy and legal framework to promote ethical and responsible use of AI is Pakistan. The country’s Ministry of Information Technology and Telecommunications released a draft National AI Policy in May 2023, while the Senate introduced the “Regulation of Artificial Intelligence Act 2024,” to regulate AI, mitigate associated risks, and penalise violations.

But even as governments and other stakeholders in South Asia confront the challenges of AI, make policies and draw up legal guidelines, one thing is clear: any regulatory framework must be undergirded by the ethics and morality of social justice and be strongly informed by the media sector as a key stakeholder.

A deathly toll

Reporting on the people’s uprising in Bangladesh came with a heavy price. Security forces shot dead four journalists and one was hacked to death by anti-government protesters in the three weeks of mass uprising in July 2024.

Pakistan bore witness to the most violent year for journalists in the country in two decades with eight journalists killed in the period under review. Most were shot by unidentified assailants, and one was caught in sectarian crossfire while reporting. The rapid declines in journalist safety and the high death toll once again places Pakistan as the deadliest country in Asia-Pacific for media workers.

The horrific murder of Mukesh Chandrakar in Bastar in Central India illustrated the hazards of reporting from conflict zones and exposing corruption. Abducted, murdered and buried in a septic tank, his body was discovered on January 2, 2025.

In Nepal, cameraperson Suresh Rajak of Avenues Television was burnt to death on March 28, 2025, while reporting atop a building in Kathmandu set alight by protestors during a violent pro-monarchy demonstration. The case once more underlined the real and present dangers for media workers on the frontline of political protests and civil unrest.

There is no doubt that India saw a spike in demand for services from AI content agencies, with political parties estimated to have spent over USD 50 million on AI-generated campaign material in 2024.

Repeated investigative failures continue to deny justice for Maldivian blogger and journalist Ahmed Rilwan Abdulla, who was forcibly disappeared by extremists on August 8, 2014. On the tenth anniversary of his abduction and murder, the Maldives Journalist Association (MJA) called for justice and a public enquiry. Impunity for the crime has prompted continued self- censorship in the media. Credit: MJA

Righting wrongs

The mighty task of tackling ever increasing levels of impunity for crimes against journalists and media workers has so far eluded most governments of South Asia. Even in the stronger democracies, a failure to bring such perpetrators to justice is a blight that continues to plague the region.

The interim government in Bangladesh is now confronted by the expansive debris of human rights violations left by Sheikh Hasina’s government. A 2025 report by the UN Human Rights Office estimates the number of deaths during the uprising at around 1,400 – around 13 per cent of them children – and thousands more injured between July 15 and August 5, 2024. A significant majority was shot by security forces. The report pointed to a media blackout enforced by the intelligence and security agencies through fear and intimidation to supress news of the brutalities on the ground. “There are reasonable grounds to believe hundreds of extrajudicial killings, extensive arbitrary arrests and detentions, and torture, were carried out with the knowledge, coordination and direction of the political leadership and senior security officials as part of a strategy to suppress the protests,” it said.

In August 2024, on the tenth anniversary of the enforced disappearance of blogger Ahmed Rilwan, human rights and press freedom groups called on the Maldives’ new government to publicly disclose the long-demanded findings of a deaths and disappearances commission set up in 2019. The tardy prosecution in this pivotal case of key national interest has undoubtedly prompted continued self-censorship in the media regarding any matters that might be termed as anti-Islamic.

Small steps were taken to tackle impunity in Nepal with the passage in August 2024 of an amendment to the Enforced Disappearance Enquiry, Truth and Reconciliation Commission Act. Nepal saw the killings of 23 journalists during its decade-long insurgency (1996-2006), and proper investigation and action against perpetrators is still awaited. However, the amendment is unlikely to provide adequate justice to the families of the killed journalists due to loopholes and inconsistency with international law. The global civil society alliance CIVICUS has currently rated the civic space in Nepal as ‘obstructed’ on account of continuing violations of civil rights including arbitrary arrests, excessive use of force and the targeting of journalists.

The struggle for justice for Sri Lankan cartoonist and journalist Prageeth Ekneligoda who was abducted and forcibly disappeared in 2010 continues. Likewise, 16 years on from his murder, justice continues to elude Lasantha Wickrematunge, the slain editor of The Sunday Leader. Following public protests, Sri Lanka’s Attorney General revoked his own recommendation to release three suspects linked to the journalist’s murder. Among other long-running cases of killings and attacks documented during the war, criminal investigators finally arrested two ex-army intelligence personnel in connection with the abduction and torture of senior journalist Keith Noyahr in May 2008.

In March 2025, the Sri Lankan government tabled the long-suppressed Batalanda Commission Report in Parliament, addressing alleged state-sponsored human rights violations, including illegal detentions and torture, during the 1988–1990 period of civil unrest. While the timing of the tabling of the report has been questioned, it allows hope that accountability for decades-old crimes may be fixed. The wheels of justice indeed turn slowly.

The civil war in Sri Lanka ended in 2009, but its repercussions continue to be felt. Tamil journalists are still singled out for harassment by both state and non-state actors. Evidencing this, journalists from the North of the country presented a memo in June 2024 to the UNHCR in Jaffna calling for a UN-led process to monitor violence against journalists in the country. Responding to government edicts prohibiting memorials to Tamil journalists and human rights defenders, in May 2024, Amnesty International issued a statement calling for justice for war victims and the right to mourn and to memorialisation. In northern Sri Lanka, the Mullaitivu Media Forum marked the 24th anniversary of the killing of senior Jaffna-based journalist Mylvaganam Nimalrajan, calling for an international investigation into crimes against journalists. It emphasised that the lack of closure perpetuated impunity and enabled perpetrators to continue without any fear of reprisals.

Attacking the messenger

Sheikh Hasina’s dramatic exit from Bangladesh further emboldened opposition-supported miscreants to target journalists, particularly in areas outside the capital, Dhaka. As many as 99 journalists were injured in 51 separate incidents through to March 2025, with 47 attacks outside of Dhaka, mostly by members of the Bangladesh National Party and the Jamaat-i-Islami.

According to estimates by the Bangladesh Federal Union of Journalists (BFUJ), almost 300 journalists and media workers were injured in 2024, many of them shot, amid the country’s rising wave of protests. Anger over news coverage led mobs to go on a rampage against individual journalists. Press clubs, newspaper offices and television studios were also attacked, equipment destroyed, broadcasts halted, and staff intimidated. The full number of these attacks is not known.

In Afghanistan, the AFJC recorded at least 172 violations against journalists and media outlets for the year up to March 2025. Its reporting highlights a 24 per cent increase in media rights violations compared to the previous year and reflects the worsening conditions for journalists and media organisations, as restrictions on press freedom continue to tighten. Meanwhile, Afghan journalists who have fled to neighbouring countries, such as Pakistan, continue to face legal uncertainties, financial struggles, persecution, legal harassment and professional isolation.

The Federation of Nepali Journalists’ (FNJ) monitoring mechanism recorded a total of 47 incidents of press freedom violations, including attacks, threats and harassment, both online and offline, by a range of perpetrators including government functionaries. The arrest of Kailash Sirohiya, chairperson and owner of two prominent national dailies, Kantipur and Kathmandu Post, and a radio and television station over issues related to his citizenship seemed a clear case of intimidation and retribution by the then-deputy prime minister, Rabi Lamichhane, who was unhappy over reporting about him.

According to estimates by the Bangladesh Federal Union of Journalists (BFUJ), almost 300 journalists and media workers were injured in 2024, many of them shot, amid the country’s rising wave of protests

Bangladesh’s journalists faced harassment, arrests, and heavy restrictions while covering national anti-government demonstrations in 2024. Students protesting near Dhaka University in Bangladesh’s capital on August 12, 2024, demanded accountability and a trial for Bangladesh’s ousted Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. Credit: Luis Tato / AFP

Narrative control

Across the region, governments attempted to shape public discourse through their hold and influence on the media and its owners.

In Sri Lanka, the media was called out for supporting alleged divisive stands and openly promoting select candidates and amplifying these messages on social media. This invited a slate of take down notices from the Election Commission.

The false promises of ensuring press freedom made by the Taliban when they took on the reins of power in Afghanistan in 2021 were quickly belied. News media in the country are, for the most part, forced to exist as a propaganda wing of the government, with independent journalism being all but crushed. Reports are closely monitored and rejected for non-compliance with the rules of the Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice, an agency set up in 1992 by the government under Burhanuddin Rabbani and now revived by the Taliban. Taboo subjects include women’s rights, social justice and human rights.

A growing list of Taliban ‘directives’, with seven more issued in the past year, now strongly dictate and control the content and format of Afghanistan’s newscasts. Bans include: criticism of Taliban officials, women’s voices, filming and recording video interviews with local officials, broadcasting of images of living beings, including animals. Additionally, terminology such as ‘martyr’ is required to be used when reporting Taliban casualties.

India’s mainstream media continued to be reined in by repression or financial harassment via the foisting of legal cases or removing the non-profit status of some of its feistier media outlets. Control was also exercised through co-option and a system of rewards and incentives through advertisements. Analysis by the BBC found that major news websites in the country published larger volumes of content mentioning the incumbent prime minister and his party, with editorials predicting his win. Attempting to legitimise sycophancy, the government of Uttar Pradesh, the most populous state in India, released the Digital Media Policy 2024 to not only regulate platforms with vague definitions of “anti-national” content, but also to develop a retinue of paid influencers. The move was vehemently opposed by journalist bodies.

International correspondents in India faced ramped up efforts to control their reporting. Work permits of several foreign correspondents were cancelled on flimsy grounds, a move that was particularly suspect during election year.

A report, Unveiling Public Trust in the Maldivian Media’ released in May 2024 found that 87 per cent of respondents held the media accountable for political divisions in the country with television and internet news websites perceived to have the highest levels of sensational or biased coverage. This was a clear wake-up call for the media to regain public trust in the atoll nation.

Information is power

Access to information, one of the lodestones of credible journalism, has been steadily declining in various parts of the region.

Afghanistan, once ranked number one of 130 countries in terms of access to information, has rapidly plummeted under the Taliban. With stringent controls over information, blocking requests, especially by women journalists, the rights once guaranteed by the Access to Information Law have atrophied. A 2024 report by the Afghanistan Journalists Support Organization (AJSO) highlights that 38 per cent of women journalists cite gender discrimination as a major barrier to accessing information, while 33 per cent fear repercussions for exposing the truth. Furthermore, 58 per cent of women journalists have no legal recourse when their requests for information are denied, underscoring the failure of Afghanistan’s current media system to uphold transparency.

In Bhutan, despite a government guideline issued in April 2024 to increase transparency and accountability, journalists reported that media spokespersons were variously unavailable or lacked the necessary information to handle media requests.

Upon assuming power in the Maldives, President Muizzu promised such high transparency in governance that the need to seek information would be redundant. However, this declaration has been belied, with the Attorney General’s office challenging orders from the Information Commissioner to comply with right to information requests. Access to events and information was linked with proximity to the government, with critical news outlets like Adhadhu refused on coverage.

A growing list of Taliban ‘directives’, with seven more issued in the past year, now strongly dictate and control the content and format of Afghanistan’s newscasts.

Women’s faces are concealed at a women’s clothing shop in Kabul, Afghanistan, after an order by the Taliban’s ‘Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice’. The de-facto government took further action to exclude women in Afghanistan society, including banning women from speaking in public, acting in television programs, or having their voices heard on radio. Credit: Wakil Kohsar / AFP

Media Closures

Job insecurity was a running theme across the region. The period under review saw ever more journalists and media workers lose their livelihoods with media closures due to government interference, revenue losses and industry job shedding.

A March 2025 report by the independent non-profit Afghanistan Journalists Center (AFJC) reported that 22 outlets closed in the past twelve months. Several radio stations were allegedly shut down by the Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice because they played background music, or allowed women to call in during live programs, thereby crossing the Taliban’s so-called “red lines.” The economic downturn also resulted in the suspension of licenses of 17 media outlets in Nangarhar due to unpaid debts. Many local media outlets are struggling to renew their licenses and even pay electricity bills and taxes. Journalists’ unions in the country estimate that almost half of Afghanistan’s 4,001 male and 747 female remaining journalists are working without salaries or employment benefits.

The major political realignments of the past year had a direct impact on the media in Bangladesh. Political retribution and perceived proximity to the ousted regime also led to mass sackings and forced resignations of senior editors, news chiefs and reporters.

India’s media saw an almost 15 per cent rise in industry layoffs in 2024-2025. Almost 200 to 400 media professionals lost jobs across print, television, and digital newsrooms in the first six months of 2024, a trend that is likely to continue. Several prominent small and medium print outlets were also forced to close down due to the high cost of printing, diminishing circulation and decline in advertisement revenue. Media closures inevitably led to an erosion in standards of decent work for media workers.

In India, a significant threat to access to information emerged in the shape of an amendment to the Right to Information Act, which was introduced in the Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act, 2023, a law that is meant to uphold the right to privacy. However, blocking access to anything termed as “personal information” even if it is public interest, is likely to impact attempts enhance institutional accountability.

Decent work challenged

The lack of decent and timely wages for journalists was highlighted in the tragic case of Nepali journalist Shyam Sundar Pudasaini, 33. The young investigative journalist collapsed upon return from work, prompting inquiries over working conditions and non-payment of wages. He is not the first journalist to die on the job waiting for rightful wages to be paid. Unsurprisingly, , the long-awaited amendments to the Working Journalists Act and fixation of minimum wages once again came to the fore in media industry and union advocacy.

A submission to the Islamabad High Court in September 2024 by the Institute for Research, Advocacy, and Development (IRADA), revealed that over 250,000 Pakistani digital media workers lacked legal protections concerning fair pay and safe working conditions. With labour laws in dire reform to include the digital sphere, a whole section of media workers remains out in the cold, with no protections.

Unpaid salaries and wage theft in Pakistan is the most critical industry issues affecting the media sector in terms of the widespread and deeply entrenched nature of the problem dating back many years. The IFJ and the PFUJ continue to lobby on the issue, demanding solutions and holding media owners accountable. A hopeful breakthrough came in November 2024, when the Standing Committee on Information and Broadcasting of Pakistan’s National Assembly finally addressed the issue of unpaid salaries for media workers and recommended stronger measures to safeguard their rights.

Restructuring measures aimed at streamlining state broadcasters in Sri Lanka are set to see a merger of Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation, Sri Lanka Rupavahini Corporation and Independent Television Network. The move, aimed at getting the broadcasters out of massive debts, will also inevitably lead to more job losses in the beleaguered media sector which is yet to recover from post-pandemic downsizing.

A submission to the Islamabad High Court in September 2024 by the Institute for Research, Advocacy, and Development (IRADA), revealed that over 250,000 Pakistani digital media workers lacked legal protections concerning fair pay and safe working conditions.

A demonstrator holds a placard protesting the new Social Media Bill tabled in Nepal’s federal parliament on February 12, 2025. The controversial bill allows authorities to ban media platforms and remove content in violation of government conditions. Unions and media stakeholders say the provisions are a government attempt to impose censorship and curtail basic human rights. Credit: Subaas Shrestha / NurPhoto / AFP

Legalised harassment

In Bangladesh, the replacement of the draconian Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Act of 2006 with the Digital Security Act (DSA) in 2018, and then the Cyber Security Act 2023 (CSA), has not led to any substantial change on the ground. Journalist bodies continued to face repression under vaguely formulated provisions. Around 5,818 cases filed under the CSA and the previous two laws currently remain pending in the country’s eight cyber tribunals.

The interim government, responding to demands for repealing or amending repressive legislation, in December 2024 released a draft Cyber Protection Ordinance. Disappointingly, it seems very similar to the CSA, for example by penalising “hurting religious sentiment” with a jail term and fine. Terming the draft as “conflicting to basic human rights,” 100 distinguished citizens issued a joint statement in January 2025 demanding it also be scrapped.

Concerns remained over Sri Lanka’s overly broad and vague Online Safety Act and its ability to severely curtail free expression. But even in the face of vehement opposition, an amendment bill was rushed through in August 2024, just ahead of the parliamentary election. In the run up to the presidential elections, a collective of 41 trade unions urged President Ranil Wickremesinghe to urgently repeal the OSA and other laws they say undermine democracy in Sri Lanka. Over 50 lawsuits are challenging the draft bill.

In India, the overuse of counter terror laws such as the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) as well as finance-related laws like the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA) against media persons has tended to promote self-censorship. Kashmiri journalists have also borne the brunt of state repression with many battling long drawn-out cases, with some serving jail terms for their reporting. Others are routinely summoned to police stations for verification, coerced into revealing sources, placed on no-fly lists, have their passports revoked or their homes raided.

Regulatory laws in India such as the Broadcasting Services (Regulation) Bill 2023 aimed at overhauling digital media regulations, continue to raise concerns about government overreach and potential censorship of OTT platforms and individual content creators. After backlash from independent media, the government withdrew a revised 2024 draft but reinstated the original 2023 version, keeping uncertainties alive over future regulatory controls.

After securing the parliamentary supermajority in the Maldives, the government proposed an amendment to the 2023 Evidence Act, which, among other concerns, allows courts to compel journalists to disclose anonymous sources in cases related to terrorism or national security. While the provision has not been enforced, the law still remains unchanged.

In Nepal, a heavy-handed approach to social media regulation saw the introduction in January 2025, of the Social Media Operation, Use and Regulation Bill. Critics argue that the bill, which criminalises online expression with harsh fines and jail terms, has potential to undermine freedom of expression and press freedom. The UNESCO review of the bill states that provisions of the bill contradict international standards and are not in line with constitutional mandates of transparency, accountability and a multi-stakeholder strategy of digital governance. The Media Council Bill, passed on February 10, 2025, though a moderate version of the earlier draft, still contains problematic provisions such as the government’s appointments of most of the council members, undermining its independence.

Pakistan’s Punjab Defamation Act 2024, with its vague and over broad definitions, makes violations punishable with massive fines, and tribunals can compel deemed offenders to issue an “unconditional apology” and direct regulatory bodies to block their social media accounts. Journalists’ bodies termed the law “draconian” and vigorously protested its enactment.

Some judicial pronouncements in India provide hope. Guaranteeing the right to free speech, on March 28, 2025, the Supreme Court of India stated that “reasonable restrictions” on the right to free speech should not be unreasonable or used to trample on citizens’ rights.

Towards equity

Despite strides made in gender equity over the decades, India’s ranking in the World Economic Forum’s 2024 Global Gender Gap Report slipped another two places to 129 out of 146 countries, and is now the third-lowest in South Asia. Its media also reflects this imbalance. Women still occupy less than a quarter of decision-making positions in India’s media and the underrepresentation of women in union leadership positions is an ongoing and pressing concern. A survey released in August 2024, revealed that over 60 per cent of women journalists were discriminated against at work based on their gender identity.

Likewise, India’s diverse ethnic and linguistic landscape is still not adequately reflected in its media, and regional languages are often overlooked in favour of Hindi and English, further limiting access to information. The representation of marginalised communities in the newsroom remains abysmal.

Women journalists in the Maldives faced harassment on the job, most of it online. At an Internet Governance Forum in October 2024, journalists spoke about harassment reaching their families and some said they were avoiding investigative journalism as a result. The response by social media platforms is less than ideal, pointing to a need to localise interventions, for example, teaming up with Meta and X to improve hate speech detection in the national language, Dhivehi, to enable journalists to push back against online harassment.

The Federation of Nepali Journalists (FNJ) made history by electing a woman journalist, Nirmala Sharma, as its chairperson for the first time in its seven-decade-long existence. With nearly 30 years of experience in the print and electronic media in Nepal, Sharma’s election comes after consistent capacity building and leadership training interventions by the women’s councils of the FNJ.

A major gender mapping project across five regions of Pakistan by the Women’s Media Forum Pakistan (WMFP) and supported by the IFJ in early 2025 revealed stark disparities, with representation as low as 3 per cent and stressed the need for intervention to increase gender equity. Globally women comprise only 24 per cent of news content, with Pakistan’s representation even lower at 11 per cent. Participants advocated for reforms including equitable inclusion and a broader movement for gender parity within the Pakistani media.

The representation of women journalists’ unions and press clubs in Pakistan’s ten largest cities was abysmally low, according to a study conducted by the Women Journalists Association and Freedom Network in early 2025. Only two press clubs (Lahore and Islamabad) reported slightly more than ten per cent share of women in their member rolls. The inclusion of women in the federal union however saw some improvement, with four women leaders elected to the new Federal Executive Council of the PFUJ.

In January 2025, journalist Asma Sherazi fought back against the harassment directed at her and other women journalists, declaring “enough is enough”. A petition from the Digital Rights Foundation, calling for an end to the systematic harassment of orchestrated attacks against media professionals by political factions and their supporters was met with widespread support among the media.

Women still occupy less than a quarter of decision-making positions in India’s media and the underrepresentation of women in union leadership positions is an ongoing and pressing concern.

Journalists in the Kashmir Valley continued to be subjected to interrogation, harassment and unlawful detention by intelligence agencies. A Kashmiri journalist films as Omar Abdullah, Chief Minister of the union territory of Jammu and Kashmir, speaks during a press conference in Srinagar on January 2, 2025. Credit: Firdous Nazir / NurPhoto / AFP

Who owns the media?

A free press is critically linked to media ownership, and every government attempts to institutionalise its support of its cronies, in return for a media that follows the official narrative.

In Bangladesh, industrialists and politicians who were bestowed media licenses by the previous government still remain loyal to Sheikh Hasina’s regime. This proximity of business interests of media owners with the government has long been a barrier to independent journalism. However, a new Media Reform Policy of 2025 drafted by the country’s interim government is finally set to address this issue. Just how impactful the policy can be remains to be seen in a country where media freedom has been stymied for so long.

The draft Media Transparency (And Accountability) Bill, 2024 in India is aimed at increasing transparency in ownership with the emergence of media monopolies; financial coercion through the misuse of the power to allocate government advertisements; and coercive actions against journalists by State and non-State actors. The bill is likely to be presented as a private member’s bill in Parliament. A report by the Press Council of India’s sub-committee on “Advertisements for print media” in September 2024 recommended that allocation be made proportional to their circulation and other qualitative parameters.

The 42 news outlets are unable to sustain themselves through private sector advertisements alone, leading to a worrying dependence on politicians, businessmen and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) that is fraught with favouritism and lacks transparency. Moreover, financial dependence on SOEs has gone hand in hand with manipulation and leverage, shaping news reportage in unhealthy ways. In February 2025, Moosa Rasheed, a senior journalist at Mihaaru, the leading local newspaper, resigned in protest over alleged government influence.

In Pakistan, government-issued advertisements continue to be a major revenue source for the media. The government reportedly allocated PKR 16 billion (USD 58.2m) in advertisements over the past five years.

The decisions by the newly-elected Trump administration to dismantle the US Agency for Global Media (USAGM) has had serious consequences for media in Afghanistan, leading to reduced funding for organisations such as Voice of America (VOA) and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL). These outlets have long provided independent news coverage to Afghanistan, and their funding cuts could weaken access to reliable information in the country.

In Bhutan, a proposal is on the anvil to put down a clear and fair advertisement policy based on market principles and explore strategies for supporting independent journalism, as well as digital media. The Social and Cultural Affairs Committee is also tasked with reviewing media legislation and policies, assessing the impact of government interventions, and evaluating public perceptions of freedom and transparency. Its report is expected by May 3, 2025.

In Bhutan, a proposal is on the anvil to put down a clear and fair advertisement policy based on market principles and explore strategies for supporting independent journalism, as well as digital media.

Aligning with the country’s shifting media landscape, the Journalists Association of Bhutan held workshops on how to pitch stories related to climate change in Thimphu on March 24, 2025. Credit: JAB

Standing together

Despite the clampdowns within borders, innovative occupation of the airwaves ensures that a few critical voices are making themselves heard. Afghan journalists in exiled media outlets such as Radio Azadi, Afghanistan International, Etilaatroz, Zan Times, and Hasht-e-Subh, remain critical of the Taliban regime.

Bangladeshi media in exile such as the Sweden-based Netra News, and Zulkarnain Saer Khan, a London-based investigative journalist in exile, have managed to expose abuse of power, rights violations and corruptions by leaders of Hasina’s party and civil and military officials associated with her government through his social media platforms.

In November 2024, journalist bodies in the Maldives mobilised around concerns related to media regulation, opposing the move to merge the media council and broadcasting commission through Maldives Media and Broadcasting Commission Bill or grounds that the would erode the self-regulatory aspect. The proposed legislation was dubbed the ‘Media Control Bill’ and a campaign, an exhibition of people’s power, with the slogan ‘Hatharehge Hagguugai’ asserting citizen power. Political will, not laws alone can enable the media to evolve with professionalism and independence.

In Nepal, the merger of the state-owned Nepal Television and Radio Nepal into the National Public Service Broadcasting Agency was welcomed, since this reform has been a decades-long demand. Former FNJ president Mahendra Bista was appointed as the first chairperson of the new entity.

Policy changes backed by financial investment proved to be of immense support to Pakistan’s media community working in some of the most challenging environments in the region. The provincial governments of Balochistan, Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa put down enhanced amounts to journalists’ welfare funds and to develop press clubs in the province – crucial hubs for the media community.

These concrete steps towards enhancing journalists’ rights stand as an example of multi-stakeholder action and vigorous solidarity in the journalist community.