AFGHANISTAN

Hitting Rock Bottom

On the third anniversary of the fall of Kabul on August 14, 2024, Taliban security personnel ride motorbikes as they celebrate near the city’s Ahmad Shah Massoud square. Since its takeover of the country, many of the hard-won achievements in media development and independent journalism over the last two decades have largely erased. Credit: Wakil Kohsar / AFP

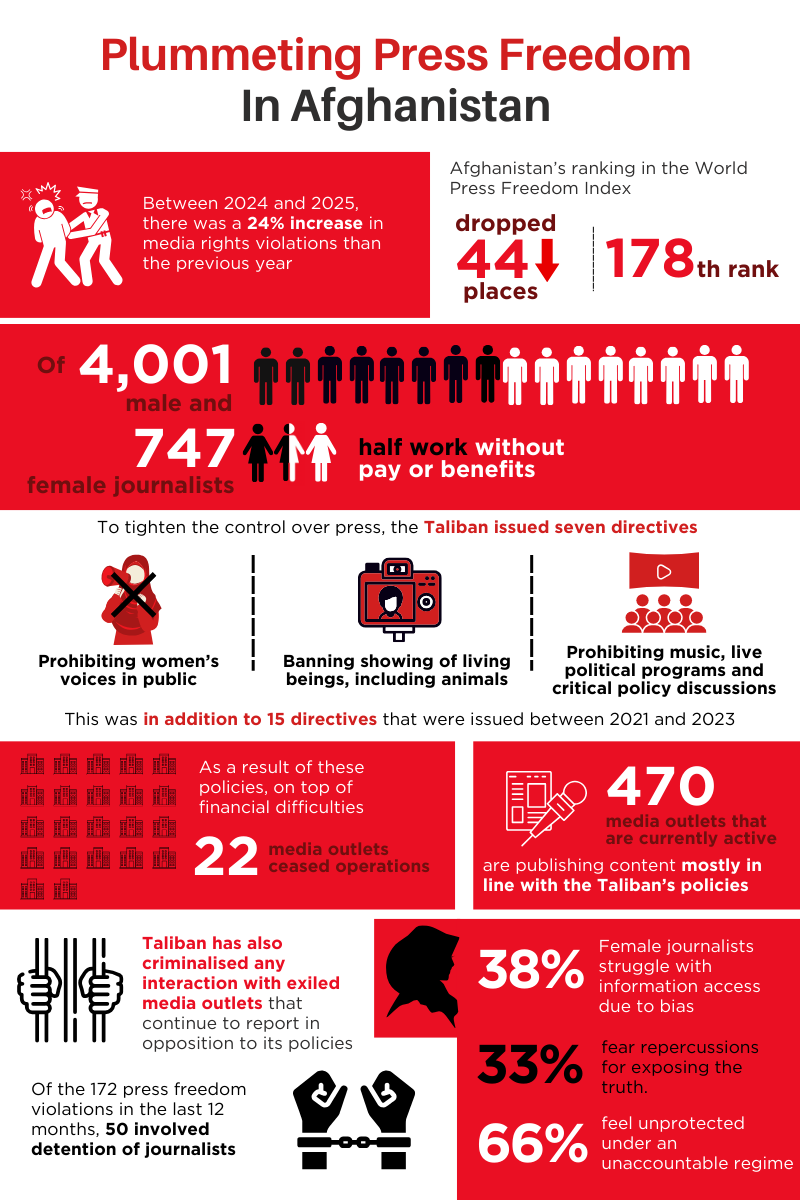

Afghanistan’s press freedom is currently at one of the lowest points in its modern history. The period between 2024 and early 2025 saw a further decline in media freedoms since the Taliban’s return to power on August 15, 2021. In the time since, the country’s independent media landscape has all but collapsed, while all the achievements in media development and independent journalism over the previous two decades have been largely erased. Media assessments from both inside and outside the country present a grim and alarming picture of the experience for media workers on the ground.

Since the Taliban declared itself the “interim” or “caretaker government’ more than three years ago, Afghanistan’s economy has imploded with the nation beset by numerous crises, leaving a huge portion of the population struggling to survive or find access to essentials. Adding to this crisis of economic contraction is the ongoing impact of the abrupt departure of the international community after Kabul’s fall, which caused the country’s GDP to fall by 28 per cent in one year alone. Without the crucial media development support and funding that was its backbone for decades, the country’s media industry is struggling to recalibrate and find economic means to survive.

The Taliban’s stringent measures have also directly transformed Afghanistan into one of the most repressive environments for journalists. Women’s rights have plummeted with restrictions on education, paid employment, movement, and political participation. So too, freedom of expression, once cherished by the Afghan public, has been effectively silenced. The 2024 World Press Freedom Index ranked Afghanistan 178 out of the 180 countries surveyed, marking a fall of 44 places from the previous year, ranking the country worse than North Korea and Iran.

Journalists, particularly those who continue to work in the country’s independent media outlets, are facing unprecedented levels of censorship. Media workers have reported to IFJ that they no longer have freedom to cover news topics objectively and are only allowed to report content that aligns with Taliban propaganda. Any deviation from this results in severe consequences, including arrests, threats, or forced silence.

In the intervening period since 2021, many outlets have either drastically reduced their operations or shut down entirely. According to a March 2025 report of the Afghanistan Journalists Center (AFJC), an independent non-governmental organisation, 22 media outlets ceased operations in the past 12 months due to a combination of reasons: economic challenges, cuts in financial support, the lack of sustainable revenue sources and also because of restrictions imposed on them.

Media outlets that dare to question the Taliban have faced shutdowns or been forced to comply with the regime’s directives. For example, Arezo TV and Bigum Radio were shut down on charges of collaborating with Afghan media outlets in exile. However, after pledging they would not engage with these exiled media organisations, they were again granted permission to resume operations.

Similarly, in 2024, Lawang Radio, Zhaman Radio, and Gharghasht Radio in Khost province, as well as Nariman Radio in Badghis province, were forcibly closed by the Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice, an agency set up in 1992 by the government under Burhanuddin Rabbani. This Ministry continued under the first Islamic Emirate under the Taliban from 1996 to 2001 and was again revived in September 2021 after the fall of Kabul to the Taliban. The closures were justified by accusations such as allowing women to call in during live programs and playing background music. Stations were only allowed to resume broadcasting after providing written commitments to adhere to the Taliban’s so-called “red lines”.

Red lines

The Taliban refer to their autocratic government, as they have for decades, as the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, though no country globally has officially recognised the Taliban as Afghanistan’s government. The UN refers to the regime as the “de facto authorities”.

Despite the Taliban’s claims of ensuring press freedom, the ground reality is very different. The country’s media has been reduced to echoing the Taliban’s views and publishing only content that supports the regime’s policies.

Nasrin, a journalist who had worked in the northern provinces of Afghanistan, described the intense pressure that journalists face. All reports that she and her colleagues produce are closely monitored and often rejected by the Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice.

Women reporters say that topics such as women’s rights and social justice issues are considered sensitive and too dangerous to cover. With every piece of work having to align with the Taliban’s ideological perspective, this leaves journalists with no room for independent thought or expression or objective reporting. “The Taliban controls everything; the news you produce must reflect their narrative. If you don’t follow it, there are severe consequences,” said Nasrin*. Reporting on anything critical is impossible, she said, and choosing the wrong words could be dangerous.

As Ahmad, a journalist in Kabul, remarked, “Even if a media outlet survives, it is no longer free. It is just a mouthpiece for the government.”

Media Rights Violations

Killings

Arrests

Without the crucial media development support and funding that was its backbone for decades, the country’s media industry is struggling to recalibrate and find economic means to survive.

The Taliban issued seven new directives during the year, including a ban on filming and recording video interviews with local officials, first enforced in the province of Kandahar and later expanded to Takhar, Badghis, Helmand, and Nangarhar. Additionally, a ban on phone calls between women and media outlets was imposed in Khost. An Afghan butcher looks on as a live broadcast of the US presidential election plays at a restaurant in Kabul on November 6, 2024. Credit: Wakil Kohsar / AFP

More bans

The AFJC reported in December 2024 that the Taliban had issued seven new directives during that year, further tightening control over the press. These included a ban on filming and recording video interviews with local officials, first enforced in the province of Kandahar and later expanded to Takhar, Badghis, Helmand, and Nangarhar. Additionally, a ban on phone calls between women and media outlets was imposed in Khost.

In October 2024, the broadcasting of images of living beings, including animals, was prohibited under Article 17 of the Law on the Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice. The Taliban also banned live political programs, critical discussions on government policies, and hosting guests without prior approval. Media were further required to use the terms “martyr” and “martyrdom” when reporting Taliban casualties.

Between 2021 and 2023, the Taliban imposed 15 directives, including bans on women working in state media, covering protests, or broadcasting music; women acting in television dramas; interviews with opposition figures; international broadcasts; films, and television serials. Criticism of Taliban officials was strictly prohibited, and in Helmand, women’s voices were banned from media. Specifically, women are not employed in state-run media and are prohibited from working there. The ban on women’s voices in the province of Helmand applied to radio and television broadcasts but did not include print media.

According to a statement issued by the Afghanistan Journalists Support Organization (AJSO) on March 18, 2025, a new directive was announced by the Ministry of Information and Culture in Kandahar, imposing a complete ban on broadcasting women’s voices, including any audio messages from women, even in entertainment programs. In a statement, the AJSO said, “The complete ban on women’s voices from media broadcasting is a blatant discrimination against women and the elimination of half of Afghan society.”

Exiled media outlets, which operate outside of Afghanistan due to the political and security situation, continue to report in opposition to the Taliban’s policies. These outlets, such as Radio Azadi, Afghanistan International, Etilaatroz, Zan Times, and Hasht-e-Subh, are critical of the Taliban regime, and the Taliban has criminalised any interaction with these media organisations.

Meanwhile, Afghan journalists who fled to neighbouring countries such as Pakistan, continue to face legal uncertainties, financial struggles, and professional isolation. While they have escaped immediate threats, they find it increasingly difficult to sustain their journalistic work under restrictive conditions.

The Taliban also banned live political programs, critical discussions on government policies, and hosting guests without prior approval. Media were further required to use the terms “martyr” and “martyrdom” when reporting Taliban casualties.

In October 2024, the broadcasting of images of living beings, including animals, was prohibited under Article 17 of the Law on the Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice. Afghan boys in Herat selling balloons sit in a vehicle after being detained by Taliban security personnel on the grounds that the balloons had faces resembling living beings, on December 23, 2024. Credit: Wakil Kohsar / AFP

Stonewalling information

The country introduced its first Access to Information Law in 2014, which was later revised in 2018. In 2019, the global Right to Information Rating ranked Afghanistan number one among 130 countries in terms of access to information. . The 2024 rating of the Access Info Europe (AIE) and the Centre for Law and Democracy (CLD) also puts Afghanistan on top, with 139 points out of 150. The rating is based on the following seven indicators: right of access; scope; requesting procedure; exceptions and refusals; appeals; sanctions and protections, and promotional measures. Despite this high rating however, under the Taliban regime, the ground reality is different. Access to government-held information is severely restricted, and the rights guaranteed by the Access to Information Law are effectively nullified in practice.

Journalists across different regions of Afghanistan report facing serious challenges in obtaining even basic, non-sensitive government information. Sharif, a journalist based in the western region, stated, “Government offices in my city refuse to speak even on topics that have no conflict with Taliban policies. When they do respond, they often ask for several days to ‘gather information’, by which time the news loses its relevance and value.”

Omid, a journalist from the southern region, expressing frustration over the accuracy of the limited information provided by the Taliban, said, “We are unable to fact-check information given to journalists. There is no way to verify their claims.” Similarly, Mahmood, a journalist from the north-eastern region, said, “There is absolutely no access to government information because no one is willing to take responsibility or provide answers.”

While government offices have appointed spokespersons, their role is largely symbolic. Journalists frequently struggle to receive timely responses, and even when information is provided, it is often incomplete, delayed, or misleading. The Taliban have established a one-way flow of select information, allowing only reports that favour their administration while blocking critical or independent coverage.

The situation is especially dire for women journalists, who face more severe restrictions in accessing information. They are barred from attending public press conferences, and government officials outright refuse to speak with them. Arezo, a journalist from the western region, shared her experience: “Every time I call a government office for information, they tell me to send my male colleague instead.”

The lack of access to accurate, timely, and verifiable information undermines press freedom and severely limits journalists’ ability to report on critical issues. Despite minor improvements in some public relations departments, these have failed to address the fundamental problems journalists face under Taliban rule. As a result, Afghan media has become one-sided, and the public remains largely uninformed about key developments affecting their lives.

Ailing media industry

The media landscape in Afghanistan has undergone a profound transformation with an economic crisis compounding the impacts of Taliban controls and resulting in severe constraints on press freedom. The Taliban’s dictates over media outlets have led to a range of restrictive measures, including the ban on film and music broadcasting, limitations on news coverage, and the stifling of editorial independence. These restrictions have not only stripped media organisations of their independence but have also dealt a significant economic blow to the industry.

Imran, a media owner from the western region, stated that his media organisation was in financial straits, with no institution offering financial support. “If there is any organisation claiming to help, it’s only in words, not in action,” he said. Similarly, Shabnam, the owner of a news website in the northern region run entirely by women journalists, explained that their media outlet had been unable to pay staff salaries for the past few years. As a result, they had been forced to suspend operations for months at a time, which she saw as clear evidence of the decline of independent and women-led media in Afghanistan.

On August 5, 2024, the Telecommunications Regulatory Authority of the Ministry of Communications suspended the frequency licenses of 17 local media outlets in Nangarhar province due to unpaid debts. Nangarhar, categorised as a first-tier province, is required to pay an annual frequency renewal fee of 108,000 Afghanis (USD 1,500) plus an additional USD 25 in administrative costs. In second and third-tier provinces, this fee is lower, but many local media outlets are struggling with debts over periods ranging from one year to over 10 years. A local radio station manager in Takhar informed AFJC that, aside from frequency license fees, the costs of electricity and various taxes had also become a heavy financial burden. He also highlighted that commercial advertisements—especially those supported by international organisations for public awareness campaigns on health, drug prevention, and peace—had significantly declined, making it even more difficult for media outlets to sustain themselves.

The very survival of the media hinges on compliance with government rules and toeing the line. Hassan, a journalist from the northern region, said, “I had carried a report on the arrest of women by the Taliban in Kabul. As a result, the Taliban arrested me and my colleagues, deleted the report from our website, and threatened to revoke our media license if we continued covering such issues.”

According to the Afghan Independent Journalist Union (AIJU), a total of 4,001 male journalists and 747 women journalists are currently working in Afghan media. However, half of these journalists — especially those in the provinces — are working without salaries or employment benefits. Even in Afghanistan’s largest media outlets, job security is not guaranteed, putting journalists at serious risk both professionally and financially.

Radio Azad in Balkh has ceased broadcasting due to financial difficulties, and Shahr ba Shahr Radio in Parwan has temporarily suspended its operations. These cases highlight the intense economic pressure on local media outlets.

The precise numbers of media closures to date still remains a point of contention. The now collapsed Afghan National Journalist’s Union (ANJU), earlier documented to the IFJ that more than half of the 623 media houses that were active before the Taliban took control had stopped operations by 2022. Yet the Afghan Independent Journalist Union (AIJU), which remains in operation in the country, issued a statement in March 2025 reporting that 470 media outlets are still active in Afghanistan, including 84 television stations, 273 radio stations, 57 news agencies, and 52 print media outlets, mostly state-run, and with content aligned with the Taliban’s policies. It contends that the primary causes of media closures in the country were related to economic challenges, cuts in financial support, and the lack of sustainable income sources. Two closures of party-affiliated outlets belonging to Hezb-e-Islami and Jamiat-e-Islami were directly closed due to political/security issues, it said.

Amid the financial crunch, news media that are compliant with the Taliban’s restrictions are growing in number. According to a government source, 11 new radio stations were launched in the past year in Kandahar, Nangarhar, Khost, Helmand, Parun, and Kabul, and one news agency was launched in Kabul.

While some media outlets continue operating under severe restrictions and economic instability, the Taliban’s increasing control over content has placed Afghanistan’s independent press in a dire state. Without urgent financial support and intervention, seemingly unlikely amid international sanctions and the cutting of international aid, more media organisations are at risk of closure, which could lead to the complete collapse of independent journalism in Afghanistan.

While government offices have appointed spokespersons, their role is largely symbolic. Journalists frequently struggle to receive timely responses, and even when information is provided, it is often incomplete, delayed, or misleading.

Two television channels in northeastern Takhar province, Mah-e-Naw and Raihan, were forced to halt operations by the Taliban after it violated the nation-wide prohibition of broadcasting living beings. The Taliban flags flutter over a provincial branch building of National Radio Television of Takhar (RTA) in Taloqan, capital of Takhar province on October 15, 2024. Credit: AFP

Intimidated and silenced

The AFJC, in its annual media freedom report published on March 16, 2025, recorded at least 172 violations against journalists and media outlets over the past 12 months. These violations included 50 cases of journalist detentions and the closure of 22 media outlets due to newly imposed restrictions by the ruling authorities. Its report highlights a 24 per cent increase in media rights violations compared with the previous year. This rise reflects the worsening conditions for journalists and media organisations in Afghanistan as restrictions on press freedom continue to tighten.

In the period under review, the AIJU welcomed the setting up of a “Journalists’ Support Fund” by the Ministry of Information and Culture but it also cautioned that the fund must be managed transparently, equitably and fairly to ensure genuine support for journalists and media outlets.

The situation for women journalists in Afghanistan has worsened significantly under Taliban rule, due to the economic crunch and non-payment of salaries, severe restrictions, gender discrimination, and a lack of access to information. According to estimates by the AIJU, the number of women journalists decreased from 2,833 before the Taliban’s return, to 747 at present, a drop of about 74 per cent.

Monitoring of the situation confronting women in media has highlighted the extreme pressures that are driving women from the industry. Those that tenaciously continue to work, face daily harassment, threats, and systematic exclusion from workspaces. While women journalists in the capital, Kabul, still manage to work and travel without a mahram (male guardian) and appear on live TV, those in the provinces are more vulnerable.

Parisa, who works in the northern region, said: “I have been threatened by the Taliban’s Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice, as well as their intelligence agency, because of my reports on women’s issues. I was threatened with arrest and repeatedly received anonymous calls and warning messages. I have changed my phone number multiple times and even relocated to a different place to ensure my safety.” She recalls a terrifying experience while covering a report on Afghan migrants expelled from Pakistan last year. “When we entered the refugee camp, Taliban members reacted aggressively, saying, ‘Who allowed this shameless woman to enter the camp?’ Even now, I still feel the fear I experienced at that moment.”

Maryam, a journalist from the western region, described how she had been denied access to information despite having official permission. “When I went to a district near my city to cover a report, I had an official letter from the Directorate of Information and Culture, but the local officials refused to speak with me.”

Somiya, another journalist, highlighted the deep-rooted gender discrimination in the media sector. “During programmes and press conferences, men are always given priority over women. There is no equality in rights between male and women journalists—women’s salaries are significantly lower than those of their male colleagues, despite having the same working conditions,” she said.

A report published by the AJSO on December 31, 2024, further highlighted the challenges faced by women journalists in Afghanistan, particularly in accessing information. The report stated that security institutions under the Taliban’s rule, particularly the Taliban Prime Minister’s Office, systematically refuse to provide information to women journalists, while on the other hand, independent analysts and healthcare workers received information with relative ease.

The report highlights that 38 per cent of female journalists cite gender discrimination as a major barrier to accessing information, while 33 per cent fear repercussions for exposing the truth. Furthermore, 58 per cent of women journalists have no legal recourse when their requests for information are denied, underscoring the failure of Afghanistan’s current media system to uphold transparency. Two-thirds of respondents pointed to the absence of legal guarantees, stating that they feel unprotected under an unaccountable regime.

The need to support and defend freedom of expression in Afghanistan, particularly for women journalists, has never been more urgent. Without intervention, Afghan women in journalism face the risk of complete exclusion from the media landscape, further silencing their voices and restricting access to independent reporting.

According to estimates by the AIJU, the number of women journalists decreased from 2,833 before the Taliban’s return, to 747 at present, a drop of about 74 per cent.

News media that are compliant with the Taliban’s restrictions are growing in number. According to a government source, 11 new radio stations were launched in the past year in Kandahar, Nangarhar, Khost, Helmand, Parun, and Kabul, and one news agency was launched in Kabul. The Taliban’s Minister of Borders and Tribal Affairs, Noorullah Noori, centre, speaks to media while visiting the site of air strikes by Pakistan in Paktika province on December 26, 2024, which killed 46 civilians. Credit: Ahmad Sahel Arman / AFP

Emerging platforms

As media restrictions and censorship have intensified, messaging platforms like WhatsApp are perceived as less secure, and apps like Telegram and Signal are increasingly being adopted by Afghan journalists operating under Taliban rule.

Telegram is emerging as a crucial platform for independent journalism, enabling news agencies and individual reporters to bypass Taliban censorship and distribute content directly to subscribers. However, this has also made journalists targets of persecution.

On August 13, 2024, Mohammad Asif Faizyar was arrested for publishing crime reports on Telegram without prior approval from the Herat Police Headquarters. He was released on August 18, 2024, but his news agency was forced to shut down. On February 27, 2025, Faizyar was detained again by the Herat Police Command, reportedly for operating a Telegram channel as a news distribution platform. He was released the next day due to AIJU’s mediation, but his agency suspended operations again.

Journalists, activists, and civil society members often turn to Signal for secure communication due to its end-to-end encryption. However, both the Taliban and the underground groups also use these platforms, creating a dangerous landscape where simply using Signal can raise suspicion and put journalists at risk.

Global ripples

Even as the crisis in Afghanistan has been upstaged by other crises in Ukraine and West Asia, some organisations are attempting to retrain the spotlight on this beleaguered country.

On March 10, 2025, the Fahim Dashty Foundation, in collaboration with Afghanistan’s Permanent Mission to the United Nations, hosted a meeting during the 69th Session of the Commission on the Status of Women in New York. Journalists, diplomats, and human rights advocates called for an end to the Taliban’s suppression of independent media and urged support for women-led media outlets, and for tackling the vexatious issue of exiled Afghan journalists.

In addition to support to media outlets in exile, interventions by the international community to those operating within Afghanistan would enhance professional capacity of in-country media. Media worker unions such as AIJU say that more effective financial and technical assistance would help ensure the continuity of independent and responsible journalism inside the country. This is particularly important in view of changing international donor priorities in the US.

Recent policy decisions by the newly elected Trump administration in the US have severely affected Afghan media. President Trump’s executive order to dismantle the US Agency for Global Media has led to a reduction in funding for media organisations such as Voice of America and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. These outlets have long provided independent news coverage to Afghanistan, and their funding cuts could weaken access to reliable information in the country. Further, new US travel restrictions will effectively close the door to thousands of Afghan journalists and media workers who were at risk from the Taliban from asylum or resettlement in the US. Many of these individuals had worked with Western media organisations and now face serious threats without a safe pathway out of Afghanistan.

These developments highlight the increasing restrictions on Afghan media, the struggles of exiled journalists, and the shrinking international support for independent reporting on Afghanistan.

[*Note: The names of all journalists quoted have been changed for their security.]

Journalists, activists, and civil society members often turn to Signal for secure communication due to its end-to-end encryption. However, both the Taliban and the underground groups also use these platforms, creating a dangerous landscape where simply using Signal can raise suspicion and put journalists at risk.

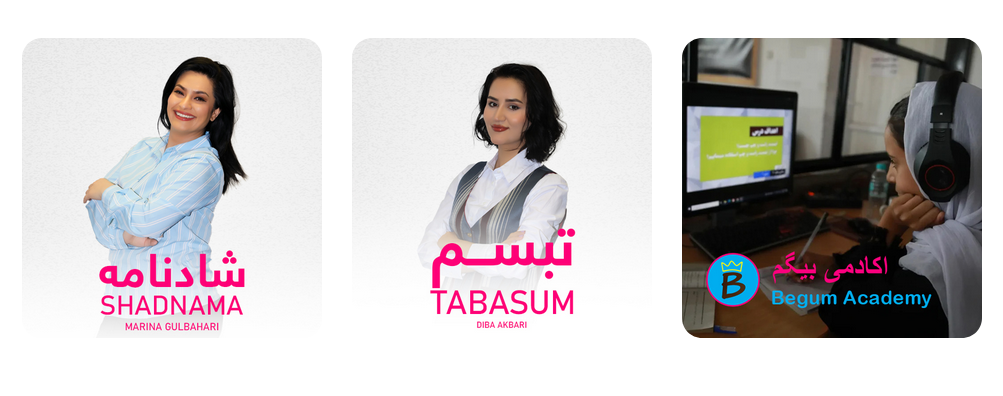

Begum TV, a Paris-based television channel broadcasting through satellite and digital platforms has emerged as a vital platform for Afghan women. The channel, launched in 2024, offers programming focused on women’s rights, education, and health — topics largely censored under the Taliban’s restrictions. Credit: Begum Organization for Women (BOW)

Begum TV: A Voice for Afghan Women in Exile

Begum TV, a Paris-based television channel, has emerged as a vital platform for Afghan women, providing education, information and hope to millions in Afghanistan. Launched on March 8, 2024, by Afghan refugee journalists in Europe, the channel offers programming focused on women’s rights, education, and health—topics largely censored under the Taliban’s restrictions.

Broadcasting in Dari and Pashto, Begum TV reaches Afghan audiences through satellite and digital platforms, circumventing local media suppression. The initiative is led by exiled Afghan women journalists who have found refuge in France and other European countries, enabling them to continue reporting despite severe restrictions at home.

Since its launch, the station with a staff of about 12, most of them women, has provided critical access to educational programmes for women and girls, many of whom have been barred from attending school. According to UN Women, the channel represents a rare lifeline for Afghan women, giving them a platform to discuss issues affecting their lives. France24 and The Guardian have highlighted the station’s role in preserving independent Afghan journalism in exile and keeping the voices of Afghan women alive.

Despite, or perhaps because of its success, Begum TV faces challenges such as financial sustainability and security threats to its contributors. However, its very existence underscores the resilience of Afghan women journalists and the enduring demand for independent reporting on Afghanistan.