INDIA

A Damaged Fourth Estate

The Indian general elections of 2024 clearly demonstrated how social media is now countering traditional media narratives. Party supporters celebrate vote counting results for the election outside Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) headquarters in New Delhi on June 4, 2024. Credit: Money Sharma / AFP

A major pillar of democracy is undergoing unprecedented upheaval in India. The media, considered a major stakeholder in the world’s largest democracy, has been shackled and subjected to a systemic strategy to cripple it. Over the past twelve years, the print and electronic media have been tamed by interventions by the government and corporate owners. Manoeuvres have been afoot to regulate the digital space.

The Union government is not alone, as ruling dispensations across the Indian states are also following suit. Every authoritarian effort is being made to crush those who seek to hold power to account—crackdowns on media houses; surveillance, intimidation and harassment of journalists; filing of police cases; arbitrary detentions; and the unleashing of raids by the Income Tax Department, and the Enforcement Directorate that oversees financial crimes.

In addition, withholding government advertisements are routine avenues to harass media houses. This ongoing mauling of freedom of speech and expression is being done on grounds of national security, maintaining public order, or preventing misinformation and disinformation.

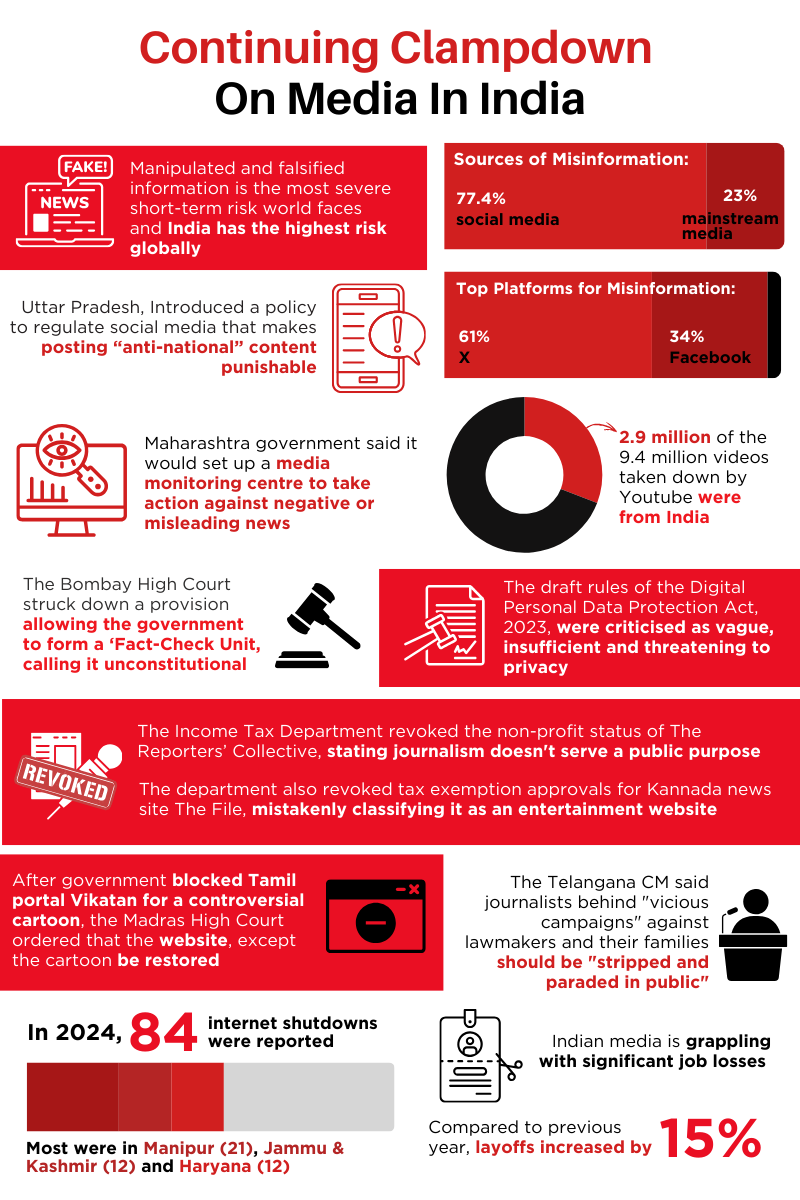

According to the Global Risks Report 2024, manipulated and falsified information is now the most severe short-term risk the world faces, and the report identifies India as having the highest risk of misinformation and disinformation globally.

The media workforce is still reeling under a shrunken job market as a result of technological advancements; growing use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) for content creation; closure of small regional media houses as well as big media houses shutting down their smaller editions during the pandemic and after; restructuring of corporate media houses because of mergers and acquisitions; decline in advertisement revenue; and new labour codes encouraging contractual work. Freelance journalism has become even more precarious.

On the flip side, the media’s digital transition has presented opportunities—growing alternative media as a counterbalance to the stagnating legacy media. There are independent online news portals which offer dissenting opinion and critiques of government actions and policies; community radio; and podcasts, citizen journalism, social media and blogs providing alternative viewpoints and reports that question mainstream narratives, giving the much-needed voice to citizens’ concerns.

Surge in digital media

According to recent data, India ranks second after China in terms of internet users, with more than 806 million individuals having internet access. Social media user penetration stood at 33.7 per cent in January 2025, with Meta, X (formerly Twitter), Instagram, and WhatsApp being the most used.

The Indian general elections, held in phases from April to June 2024, and elections to state Assemblies running into 2025, are a testimony to the role social media is playing in countering traditional media as well as providing new avenues for political discourse, and often allowing voices critical of government to be heard.

At the same time, there has been an unprecedented surge in digital advertising spending, reflecting the growing importance of social media marketing. While the total election budget for political parties collectively reached INR 13,000 crore (approximately USD 1,510 million) across various media platforms, the spending on digital ads alone increased significantly.

With growing internet penetration and with the availability of affordable data as well as smartphones, political parties in India are now increasingly engaging YouTube and Instagram influencers to post hyperlocal content. Studies reveal that social media has intrinsically transformed the way political parties and voters engage in the electoral process.

Social media platforms, AI-driven strategies, and ‘influencers’ were actively used to reach out to the electorate. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has been the leading party in the online space, but other parties are catching up, investing in IT and social media units to build their digital presence.

In the run-up (April 2024) to the elections, AI content agencies reported a huge surge in demand, with political parties in India projected to spend over USD 50 million on AI-generated campaign material that year.

Reports reveal that social media platforms are the dominant source of misinformation, responsible for 77.4 per cent of cases compared to just 23 per cent originating from mainstream media. X (61 per cent) and Facebook (34 per cent) were identified as the leading platforms for spreading fake news.

The role of social media platforms in the dissemination and amplification of verified in-person hate speech during gatherings in India in 2024 was a matter of concern. A report ‘Social Media and Hate Speech in India’ by the Centre for the Study of Organised Hate Speech, says that social media platforms—Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, YouTube, Telegram, and X—were key instruments in enabling, amplifying, and mainstreaming hate speech and extremist ideologies in India, as was the case globally. In the Indian context, these platforms were extensively utilised by senior leaders to articulate and spread Hindu nationalist ideology and anti-minority rhetoric. Provocative hate speeches, including clear calls for violence, were first shared or livestreamed on social media platforms, mainly Facebook and YouTube.

Media Rights Violations

Killings

Arrests

In the run-up (April 2024) to the elections, AI content agencies reported a huge surge in demand, with political parties in India projected to spend over USD 50 million on AI-generated campaign material that year.

India’s digital transition presents opportunities for growing alternative media as a counterbalance to the stagnating legacy media. Independent online news portals offer dissenting opinion and critiques of government actions and policies, while community radio, podcasts, and blogs provide alternative reports that question mainstream narratives. Drones form the map of India at the Cyber Hackathon 1.0 at Rajasthan Police Academy in Jaipur, Rajasthan, India, on January 16, 2024. Credit: Vishal Bhatnagar/NurPhoto via AFP

Narrative control

Legacy media too was polarised, particularly during the elections. A BBC Monitoring Explainer published on May 1, 2024 found that major news websites in the country had larger volumes of content mentioning the incumbent prime minister and his party. During the same period, election-related editorials by top English and Hindi newspapers stressed that the BJP had stronger prospects in the elections than the Opposition. A forecast that ultimately rang true.

Research by academics Kiran Garimella and Abhilash Datta released on March 29, 2024, found that over 60 per cent of one of India’s most prominent and widely-watched TV news debate shows, ‘Arnab Goswami – The Debate’, featured content favouring the ruling party. Additionally, social media amplification and support for the show predominantly came from the BJP’s supporters.

With legacy media largely co-opted or cowed down, governments are increasingly wanting to control as well as shape the social media narrative through a policy of reward and punishment.

Taking the lead, the government of Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, launched a Digital Media Policy 2024 to regulate content on platforms like Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and X, wherein posting ‘anti-national’ content is punishable with jail terms from three years to life imprisonment, and obscene and defamatory content posted online could result in criminal defamation charges being brought by the government.

Secondly, the policy aims to regulate advertising and oversee the display of videos, tweets, posts and reels. More importantly, influencers will be paid for creating content, videos, tweets, posts, and reels that promote the government’s welfare schemes and achievements. Rates have been fixed, where influencers on X, Facebook and Instagram will be paid between INR 3-5 lakh (USD 3000- 5000) per month. YouTube influencers will have different payment caps depending on the type of content they produce.

Journalist bodies, including the Indian Women’s Press Corps, Press Association, DigiPub News India Foundation, and the Software Freedom Law Centre, demanded immediate withdrawal of clause 7(2) from the Digital Media Policy-2024, stating that the provision gave sweeping powers to the State government to declare any content, including legitimate journalistic work posted on social media, as “anti-social” or “anti-national”.

In the state of Maharashtra too, a government resolution issued in March 2025 declared that it would set up a media monitoring centre to observe positive and negative news coverage related to the government in print, electronic, social and digital media, and take action against negative or misleading news. Journalists see this as another form of surveillance that could have a chilling effect.

The clampdown has led to independent and reputed journalists starting their own YouTube channels, with some having viewership running into millions. However, whether this approach can withstand the pressure is unclear.

India had the highest number of YouTube videos taken down globally over the last three months of 2024. Out of a global total of 9.4 million videos, over 2.9 million YouTube videos were removed by the Google-owned platform between October and December last year, for violating its community guidelines.

The ongoing tussle between platforms and governments over regulation is apparent in the case filed by Elon Musk against the government of India. In a hearing in the Karnataka High Court on March 29, 2025, the government denied the claim made by X that the SAHAYOG portal was a tool of censorship. However, X has refused to join the centralised portal the government claims is meant to facilitate coordination among law enforcement agencies, social media platforms, and telecom service providers.

An amendment to the Right to Information Act, which was introduced in the Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act, 2023, a law that is meant to uphold the right to privacy, represents a significant threat to access to information. Blocking access to anything termed as “personal information” even if it is public interest, is likely to impact attempts enhance institutional accountability.

Judicial breather

Notably, a judiciary that upholds constitutional rights is crucial to a floundering democracy and offers a ray of hope. On March 28, 2025, in a definite verdict on free speech, the Supreme Court of India quashed the First Information Report (FIR) against Member of Parliament Imran Prataphgarhi for sharing an allegedly “provocative poem” online. The apex court stated that “reasonable restrictions” on the right to free speech should not be unreasonable or used to trample on citizens’ rights, and that the effect of words could be judged on the basis of “the standards of people who always have a sense of insecurity or of those who always perceive criticism as a threat to their power or position”.

Likewise, on October 4, 2024, the Supreme Court barred the Uttar Pradesh police from taking coercive steps against a journalist for his post on X about a “casteist tilt” in the deployment of officers occupying key positions in the state administration. It said: “In democratic nations, freedom to express one’s views is respected. The rights of the journalists are protected under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution. Merely because writings of a journalist are perceived as criticism of the government, criminal cases should not be slapped against the writer.”

In yet another case, on March 6, 2025, the Madras High Court directed the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting to restore access to the website of Tamil media group Vikatan, except for the impugned cartoon. The website had been blocked without prior notice or an official order, on February 15 over a satirical cartoon related to deportation of Indian immigrants to the US. The Union government had claimed the cartoon threatened India’s sovereignty and “friendly relations” with foreign states.

On March 17, 2025, the Karnataka High Court quashed a hate speech case against CNN News18 consulting editor Rahul Shivshankar over his post on X about the state government’s allocation of funds for the welfare of religious minorities.

On May 15, 2024, the Supreme Court ordered the release of NewsClick founder and editor-in-chief, Prabir Purkayastha, from Delhi’s Tihar Jail after declaring that his arrest, under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act was “invalid”, as the grounds of arrest had not been supplied in writing to him or his counsel before his remand. Purkayastha had been in jail since November 2023.

With legacy media largely co-opted or cowed down, governments are increasingly wanting to control as well as shape the social media narrative through a policy of reward and punishment.

In a definite verdict on free speech, the Supreme Court of India quashed the First Information Report (FIR) against Member of Parliament Imran Prataphgarhi for sharing an allegedly “provocative poem” online.

Considered a major stakeholder in the world’s largest democracy, the media has been shackled and subjected to a systemic strategy to cripple it. DigiPub, a consortium of digital news portals said, “The government’s claim that journalism does not serve a public purpose is deeply disturbing and antithetical to the foundation of a democracy.” A women scatters flower petals on a poster of Mahatma Gandhi on the occasion of his 155th birth anniversary on October 2, 2024. Credit: Firdous Nazir/NurPhoto via AFP

Choking independent websites

The courts striking down arbitrary orders to safeguard freedom of speech did not seem to deter the government from flexing its muscles. Ominous signs of censoring independent news regularly appeared in the period under review. Continuing a pattern of using central agencies to harass the media, The Reporters’ Collective, which produces investigative journalism in multiple formats and languages, with some reports critical of the government, was dealt a blow by the Income Tax Department in January 2025. In a statement, the Collective said, “…tax authorities have cancelled our non-profit status, claiming journalism does not serve any public purpose and therefore cannot be carried out as a non-profit exercise in India…The order severely impairs our ability to do our work and worsens the conditions for independent public-purposed journalism in the country…”

In a statement on March 3, 2025, DigiPub, a consortium of digital news portals said, “The government’s claim that journalism does not serve a public purpose is deeply disturbing and antithetical to the foundation of a democracy.” Earlier, in December 2024, the Income Tax Department rescinded Kannada news website The File’s approvals for tax exemptions, wrongly claiming it was an entertainment website.

Indeed, the rise of digital and social media has changed the dynamics of press freedom. In the past year, the government has continued to implement policies aimed at regulating digital platforms, such as the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules; the proposed Broadcast Services (Regulation) Bill, 2023; the Press and Registration of Periodicals Act, 2023; the Information Technology Amendment Rules, 2023; and the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023.

The Digital Personal Data Protection Rules, 2025 (“Draft Rules”) were published on January 3, 2025, for public consultation. The Internet Freedom Foundation found the Draft Rules to be “too little, too vague, and too late”, leaving room for discretionary interpretation by the government, and arming it with power to compel data sharing under vaguely defined circumstances, which could lead to surveillance and undermine privacy protections.

These regulations raise concerns about excessive state control over online content, and the potential for censorship, leading to fears of restricting the free flow of information. Media organisations, including the Press Club of India, Indian Journalists’ Union, Delhi Union of Journalists, DigiPub News India Foundation, Internet Freedom Foundation, Working News Cameramen’s Association, Indian Women’s Press Corps, Cogita Media Foundation, and press clubs of Mumbai, Kolkata, Thiruvananthapuram and Chandigarh, met on May 24, 2024 in Delhi and resolved to intensify the demands of the media and digital rights organisations. They urged the Union government to withdraw laws such as the proposed Broadcast Services (Regulation) Bill, 2023; the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023; the Press and Registration of Periodicals Act, 2023; and the Information Technology Amendment Rules, 2023, which they said would curb freedom of the press.

Sadly, the demand fell on deaf ears. March 2025 saw the arrest of Tushar Abaji Kharat, editor of Lay Bhari, a local YouTube channel in Maharashtra, and two women journalists, P Revathi and Thanvi Yadav of online news channel Pulse News in Telangana, both on grounds of defamation. The remarks of the chief minister of Telangana, that journalists who post “vicious campaigns” against public representatives and their family members “should be stripped and paraded in public” and that media organisations, media associations, information and PR departments, and authorised news agencies should “define and identify” legitimate journalists seemed like excessive control.

On the flip side, in a report of the Press Council of India’s sub-committee on Accreditation released on September 27, 2024, members expressed displeasure that in most of the states no proper representation was given to journalist bodies on Accreditation Committees. Some states have not formed the committees for the past over 20 years and journalists are at the mercy of government officials and politicians who want to control the media through accreditation.

Brazen targeting

The legal environment for the press has become increasingly hostile in recent years. The use of defamation laws, sedition charges, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) and Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), have raised concerns about media freedom. Journalists and media houses have faced legal challenges for publishing reports critical of the government, which has led to self-censorship within the industry, following a chilling effect. A case which hit national headlines is that of The Hindu’s Gujarat correspondent and senior journalist Mahesh Langa. He has been languishing in jail since October 25, 2024, with seven cases filed against him: five FIRs by Gujarat Police and two cases by the Enforcement Directorate for allegedly possessing ‘confidential files’ of Gujarat Maritime Board and for ‘money laundering’.

The arrest of Dilwar Hussain Mozumder, chief reporter of digital media portal, The Cross Current and assistant secretary of the Guwahati Press Club on March 25, 2025, following his coverage of a demonstration against alleged corruption within Assam Co-operative Apex Bank Ltd led to an uproar in the media community. The Guwahati Press Club, Indian Journalists Union (IJU), Editors Guild of India, Press Club of India, the Journalists Union of Assam and others protested, condemned the arrest of Mozumder, and expressed shock by the statement of Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma that journalists working in news portal are not recognised as journalists by the state government.

Journalists reporting from conflict zones, or those exposing corruption, and the politician-mafia nexus, have had to pay a heavy price with their lives. On May 13, 2024, journalist Ashutosh Srivastava was fatally shot by unknown persons in Jaunpur, Uttar Pradesh. On September 17, 2024, broadcast journalist Salman Ali Khan was fatally shot by unknown assailants in the western Rajgarh district of Madhya Pradesh. On January 3, 2025, the body of freelance journalist and contributor to NDTV Mukesh Chandrakar in Bijapur district of Chhattisgarh was found in a newly concreted septic tank on the property of a private contractor. Investigation revealed that he was killed for reporting irregularities in road construction work.

On March 8, 2025, a local journalist and RTI activist Raghavendra Bajpai was fatally shot in broad daylight in Uttar Pradesh’s Sitapur district. The Press Council of India took suo-motu cognisance of the killing. On June 25, 2024, digital journalist Shivshankar Jha, 48, sustained multiple wounds to his throat while returning to Maripur village, near Muzaffarpur, Bihar, after being stabbed by unidentified persons, allegedly linked to the illicit liquor mafia in the state.

Journalists across the country were subjected to attacks and intimidation. On May 13, 2024, Raghav Trivedi was hospitalised after an assault by political activists, allegedly linked to the BJP, at a demonstration in Raebareli district in Uttar Pradesh. On May 31, 2024, Vinay Pande, an independent journalist in Nagpur, Maharashtra registered a police complaint after receiving death threats on Instagram, including a message threatening to behead him. On June 1, 2024, freelance journalist Bunty Mukherjee was severely injured during violent clashes reportedly between political activists on last day of voting in a town east of Kolkata, West Bengal. On May 23, 2024, journalist Ankur Jaiswal was allegedly assaulted by local politician Satish Bhau and others at a private event in the Banganga area of Indore, Madhya Pradesh. In Agartala, capital of the northeastern state of Tripura, on September 8, 2024, four journalists were assaulted by armed men near Chandrapur Inter-State Bus Terminus past midnight.

On January 21, 2025, Abdul Majan, a journalist working with a news portal in Assam, was arrested by the police for ‘falsely’ reporting about a hit-and-run case allegedly involving the son of an influential politician. He was granted bail after being presented in court.

On December 18, 2024, the police used tear gas against journalists in Guwahati while covering a protest rally.

On August 1, 2024, broadcast journalist M Rameshchandra, was brutally assaulted by a policeman while covering a rally in Manipur’s Imphal East District. Uttarakhand journalist Pramod Dalakoti’s was assaulted and robbed while reporting on a clash between two student groups at a private college on September 28, 2024. On July 16, 2024, Khoirom Loyalakpa, the editor of Naharolgi Thoudang, was attacked by unknown assailants at his residence in Imphal East District, in Manipur. In most cases, the perpetrators of crimes against journalists go unpunished which encourages further attacks.

A report ‘Arrests, wrongful detention and intimidation of media personnel’ by member Gurbir Singh, adopted by the Press Council of India on August 2, 2024, read: “Every year the Press Council receives hundreds of complaints in respect of violation of press freedom and suppression of free speech. Complaints by journalists and news media organizations against the Union or state governments, against specific ministers or government functionaries, and often against law enforcement agencies for misusing their executive powers to curb the freedom of reporting by threats, arrests, physical violence and in some cases even death and disappearances…” Further to this the report added: “Law enforcement persons, acting on the orders of superiors, instead of protecting press persons become handmaidens of vested interests and criminal elements, and play an active part in threatening or attacking journalists and ensuring their voices are muzzled.” The PCI Chairperson Justice Ranjana Prakash Desai dissented with what she called a “one sided report”.

In the backdrop of increasing threats on safety and security of journalists, there have been demands for a Journalist Protection Act in India to provide safeguards for journalists and ensure accountability. In May, a draft of the Media Transparency (And Accountability) Bill, 2024 was prepared by a team of lawyers and shared with media organisations and journalists trade unions in Delhi. The draft bill is to curb three challenges: Lack of transparency of ownership with the emergence of media monopolies; Financial coercion through the misuse of the power to allocate government advertisements; Coercive actions against journalists by State and non-State actors. It was proposed that it be presented as a private member’s bill in Parliament.

The use of defamation laws, sedition charges, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) and Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), have raised concerns about media freedom.

During the Indian general elections in 2024, there was an unprecedented surge in digital advertising spending, reflecting the growing importance of social media marketing. The total election budget for political parties collectively reached INR 13,000 crore (approximately USD 1,510 million) across various media platforms. A giant screen displays a photo of Prime Minister Narendra Modi ahead of the Lok Sabha election in Mumbai, India, on April 17, 2024. Credit: Indranil Aditya/NurPhoto via AFP

Clampdown on international media

The government is increasingly intolerant of adverse reportage and several foreign correspondents are finding it difficult to obtain visas, or renew work visas or permits allowing them to work in India.

Raphael Satter, a Washington-based cyber security journalist, reporting for Reuters took the government to court in March 2025, following cancellation of his Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) status on grounds that his work ‘maliciously’ tarnished the country’s reputation. Satter was accused of “maliciously creating adverse and biased opinion against Indian institutions in the international arena”. Revocation of Satter’s OCI followed his report on the Indian cybersecurity company Appin and its co-founder Rajat Khare.

OCI status is given to foreign citizens of Indian origin, or those married to Indian nationals, and allows for visa-free travel, residency and employment in India. Satter received his OCI through marriage. In recent years, the ruling party has been accused of revoking OCI privileges for those it has deemed critical, part of what Human Rights Watch has called a campaign of “politically motivated repression”. Journalists, academics and activists have been a particular target. Several high-profile journalists have been forced to leave the country after their OCI cards were revoked.

On June 20, 2024, Sébastien Farcis, a French journalist working for Radio France Internationale, Libération and the Swiss and Belgian public radios, announced on social media the government’s refusal to renew his work permit with no explanation. He is among two other foreign journalists who were forced to leave the country in 2024 as their journalist work permits were not renewed.

In April last, Avani Dias, who worked as ABC News South Asia bureau chief, said that the Indian government denied her a visa extension after she published a report on the killing of a Sikh separatist. Her story is still blocked on YouTube in India. She received a visa extension to cover the 2024 elections just a day before she was scheduled to leave the country. By then, she said, it was too late.

About 30 foreign correspondents based in India – reporting for the Financial Times, the Washington Post, France 24, The Guardian, the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal and others – signed an open letter protesting the treatment meted out to Dias.

A journalist permit was denied to French journalist, Vanessa Dougnac, based in Delhi, and married to an Indian national. She had been working as the regional correspondent for French, Swiss, and Belgian newspapers for more than two decades. The Indian government said she had violated “rules and regulations.” She was forced to leave India in February 2024. More than a year later, on March 27, 2025, she was issued a one-year work permit to resume her work as foreign correspondent based in New Delhi.

Internet shutdowns

Internet shutdowns have become a rule rather than an exception. For the first time since 2018, India in 2024 did not lead the world in internet shutdown orders in a year. According to non-profit digital rights advocacy group Access Now, Myanmar ordered the highest number of shutdowns at 85, edging out India that enforced 84 similar orders the previous year. Internet services were shut down in India due to conflict, protests and instability, communal violence, to prevent cheating in exams, and elections.

At least 41 internet shutdowns were related to protests and 23 to communal violence. Sixteen state and union territories were affected by internet shutdowns in 2024 with Manipur (21), Jammu and Kashmir (12) and Haryana (12) leading the list. Since May 2023, the northeastern state of Manipur has been on the boil, with armed ethnic conflict and deeply polarised communities vulnerable to misinformation online. However, internet shutdowns also adversely affected the ability of independent journalists to verify rumours and publish credible news.

Bots in the newsroom

Like in other parts of the world, the emergence of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has raised apprehensions in India. Discussions are going on about the convergence of AI and journalism. It is clear that while AI may present many opportunities, it also poses significant challenges, such as the integrity of editorial content, job security within the industry, copyright infringement and the authenticity of information disseminated to the public.

While the adoption of AI is enhancing efficiency and productivity in journalistic work, this approach may not necessarily prioritise the welfare of journalism or the needs of audiences. Not every problem the media faces can be addressed with the help of technological solutions, as it is not human judgement and does not adhere to the rigour of professional journalism. AI algorithms can perpetuate existing biases, leading to skewed or misleading information. Over dependence on AI-generated content may result in loss of diversity and unique perspectives.

The government is increasingly intolerant of adverse reportage and several foreign correspondents are finding it difficult to obtain visas, or renew work visas or permits allowing them to work in India.

Legacy media was also polarised during the Indian national elections. Election-related editorials by top English and Hindi newspapers stressed that the ruling BJP party had stronger prospects in the elections than the Opposition. A forecast that ultimately rang true. A vendor arranges newspapers with front pages of India’s general election results, in New Delhi on June 5, 2024. Credit: Arun Sankar / AFP

Advertisement crunch

Concern over government using its advertisement budget to muzzle critical media outlets has been increasing. The government’s selective allocation of advertisements to ‘friendly’ media outlets, while withholding them from independent ones, puts a question mark on the authenticity of news and its coverage in media, which is increasingly showing signs of bias

Not only at the Centre, but in the states of Assam, Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh for example, among others there are serious concerns about the discriminatory distribution of government advertisements to friendly media outlets, while withholding them from critical or the independent ones. The discrimination in allocation of advertisement revenue is being adjudicated in the Gauhati High Court in Assam.

Likewise, the Bombay High Court on October 28, 2024 noted that in the Common Cause Case, one of the concerns addressed was the misuse of publicly funded advertising campaigns through print and electronic media by the government. The Supreme Court issued directions based on the recommendations of a High-Power Committee.

A report by the Press Council of India’s sub-committee on ‘Advertisements for Print Media” in September 2024 stated: “The print media has been facing significant challenges in recent years, including Covid, declining advertisement revenues, competition from digital media…There is an urgent need for fair distribution of advertisements. Enhancing the budget for the print media and treating it as a separate entity from other forms of media could help it face the challenges.” The sub-committee recommended that allocation be made proportional to their circulation and other qualitative parameters.

Unequal and exclusive

India’s ranking in the World Economic Forum’s 2024 Global Gender Gap Report is alarming, slipping two places to 129th out of 146 countries. The country has only managed to close 64.1 per cent of its gender gap, placing it fifth in South Asia after Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Bhutan. This ranking is a reflection of the persistent gender inequality issues in India. Women’s representation in the media is one such area of concern.

Women still occupy less than a quarter of decision-making positions in media outlets and face issues of online trolling and gender pay gap. The underrepresentation of women in union leadership positions is a pressing concern. The report of a Statistica survey released in August 2024, revealed that over 60 percent of women journalists had been discriminated against at work based on their gender identity. In comparison, 80 percent of male journalists had never faced gender-based discrimination in their workplace.

Likewise, India’s diverse ethnic and linguistic landscape is still not adequately reflected in its media. The contentious point is that regional languages are often overlooked in favour of Hindi and English, limiting access to information and representation for marginalised communities. Given the poor representation of Dalits in the media, some Dalit-led news portals such as Mooknayak and Dalit Voice are attempting to fill this void.

Trust deficit

A growing concern is a trust deficit in media outlets. According to another survey conducted in India in 2024 by Statista about 67 percent of respondents trusted the media. But there was an increasing concern about the spread of fake news, misinformation, and propaganda, especially during election periods. While the government has blamed certain media outlets and social media platforms for spreading fake news, critics argue that the government’s attempts to regulate these platforms are a means of controlling the narrative.

In a small pushback to the government’s unrelenting attempt to control the media, on September 20, 2024, the Bombay High Court struck down the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Amendment Rules, 2023, which allowed the Central Government to form a Fact-Check Unit to identify online content regarding government business as “fake, false, or misleading”. It said these were unconstitutional and did not satisfy the “test of proportionality”.

The government’s selective allocation of advertisements to ‘friendly’ media outlets, while withholding them from independent ones, puts a question mark on the authenticity of news and its coverage in media, which is increasingly showing signs of bias.

The use of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA) and sedition charges have raised concerns about media freedom. Journalists and media houses have faced legal challenges for publishing reports critical of the government, which has led to self-censorship within the industry. Media working on results day of India’s 2024 general election at the Indian National Congress headquarters. Credit: InOldNews

Challenges in the Valley

The situation in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) continues to be challenging for journalists. In October 2024, the first elections after Article 370, which granted special status to Jammu and Kashmir was abrogated, and the state was downgraded to a union territory, brought a regional party to power, albeit with clipped wings under what remains for all intents a centrally administered territory. On the eve of the elections in Jammu and Kashmir, Amnesty International called upon the authorities to “stop using restrictive travel bans and arbitrary detentions under the country’s stringent anti-terror laws to intimidate critical dissenting voices from speaking out on Jammu and Kashmir”.

A September 2024 report by the Newslaundry, investigated conditions on the ground for journalists and found media workers were still regularly subjected to interrogation by one or the other many central intelligence agencies active in the state while others are continuing to languish in jails under the Public Safety Act or anti-terror laws. These cases are being closely followed by the IFJ and others in the press freedom community.

A ‘New Media Policy’ is on the anvil, with the validity of the Media Policy 2020, opposed by media bodies and political parties, ending this year. The Omar Abdullah government said in March 2024 that the policy would “encompass emerging platforms including social media platforms, new web portals and websites”. However, it steered clear of issues like free speech and press freedom, wherein the legal environment for journalists was increasingly repressive.

A big question mark hangs on whether the pervasive climate of fear among journalists will change. On the one hand, the answer could be a big no. The DigiPub News India Foundation has raised serious concerns over a recent threat of legal action by the administration against The Chenab Times, a digital news outlet based in Doda district, which published a report covering the detention of a local activist from Doda under the Public Safety Act (PSA) and posted a video on its Facebook page. In a letter dated November 12, 2024, the Department of Information and Public Relations referred to it as an “irrelevant post” and alleged the video content “prejudiced the due process of law,” created “rumours” and portrayed the district’s administrative procedures in a “bad light,” claiming it risked public order. The district information officer warned of legal action. The foundation condemned what it described as an attempt to stifle press freedom.

On the other hand, the courts may raise hope. On January 2, 2025, the Jammu and Kashmir High Court quashed the preventive detention order passed against Tarun Behl, who owns two newspapers in Jammu, calling it “malice-inducing and unlawful.” Behl was arrested in three criminal cases and served one preventive detention order in two months. The preventive detention order was passed on the same day he was granted bail in the third case in September 2024. Said Justice Rahul Bharti that the petitioner’s ultimate arrest and detention in September was “a pointer to the fact that the petitioner was somehow being eyed upon to be a witch-hunt by the authorities and that is exhibited from the aforesaid sequence.”

On February 19, 2025, the Jammu and Kashmir High Court quashed the preventive detention order against journalist Majid Hyderi, who worked with a local digital news platform. The court ruled: a government critic cannot be put under preventive detention in the absence of a “live and proximate link” to a law-and-order problem. The 23-page judgement noted the “vague and ambiguous” grounds cited in the PSA dossier of Hyderi had “invaded (his) constitutional rights” which “violates fundamental right to life and personal liberty of the detenu under Article 21 of the constitution”.

Likewise, a victim of the revolving door of continuous arrest, on May 10, 2024, journalist Aasif Sultan was finally granted bail by a court in Srinagar. Released on February 27, 2024, after nearly six years of incarceration, Aasif Sultan was re-arrested merely two days later. He was accused of multiple offenses including those under the UAPA. While granting him bail, the court stated that merely invoking the UAPA is not enough to warrant rejection of bail applications.

The September 27, 2024, report of the sub-committee of the Press Council of India to evolve guidelines for the media, police and security forces on reporting in conflict situation particularly in North-Eastern States, Naxal affected areas and J&K noted that after the abrogation in 2019 of Article 370 granting Jammu and Kashmir special status, “The pressure of separatist-terrorist groups and organizations on journalists and journalism declined while the government pressure increased. In most of the cases, the media has to work with the help of government information and press releases. If a journalist disagrees with the government and tries to do fact-based journalism, then the advertisements to his newspaper are stopped, such journalist-editors are arrested under critical sections in old cases by declaring them anti-national. Many journalists have also been arrested on the charge of terror funding. The Kashmir Press Club, which gave a platform to the voices of dissent against the government, was closed on the pretext of factionalism.”

The report noted that there was a difference of opinion about press freedom between local journalists and those reporting for the national media. The former claimed there was freedom of press after revocation of Article 370, whereas the latter said that journalists were being arrested under serious sections by making them accused in old cases.

What is clear, is that while much critical journalism has been seriously silenced in the region, Indian and global independent media are continuing to shine a light.

Eroding labour rights

Into its third term, the Centre is setting the stage for the possible implementation of the four Labour Codes, passed five years ago by Parliament. Almost all the States have framed the draft rules, but the Centre is yet to notify these. Central Trade Unions (CTUs) had opposed the implementation of the codes citing these will curtail trade union’s rights and social security measures for workers.

Journalists’ bodies had decried the new labour laws criticising that the new labour laws will further deteriorate the working conditions of journalists and their social security. The rights of working journalists embodied in the Working Journalists and other Newspaper Employees (Conditions of Service) and Miscellaneous Provisions Act, 1955 (WJA Act), which is repealed by the Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code, 2020 [‘the OSH Code’]. The OSH Code is one of four Labour Codes being sought to be brought in by the Central Government in the interest of ‘ease of doing business’, which collectively repeal 44 existing enactments.

These Codes are far from benign; they remove significant protections of workers across the board in the name of streamlining. Journalists’ organisations condemned the Labour Codes and demanded restoration of the Working Journalists’ Act (WJA), bringing digital media under the ambit of the Act and reiterating the long standing demand to set up an independent Media Commission to address journalists’ welfare and harassment.

Journalists’ bodies had decried the new labour laws criticising that the new labour laws will further deteriorate the working conditions of journalists and their social security.

Since May 2023, the northeastern state of Manipur has suffered armed ethnic conflict, and internet shutdowns have adversely affected the ability of independent journalists to verify rumours and publish credible news. ‘Meira Paibis’,or women activists, hold torches during a protest rally in Imphal demanding justice for a missing man from the Meitei community and restoration of peace in Manipur on December 5, 2024. Credit: AFP

Seismic shift

The Indian media industry is undergoing a seismic shift, and the road ahead will be challenging. The decline of legacy media outlets and the rise of digital media are marking a shift in the job market. Indian media is grappling with significant job losses and a rise in layoffs in 2024-2025. According to reports it amounts to 15 per cent rise in layoffs compared to the preceding year. Data from industry sources reveal that almost 200 to 400 media professionals have lost their jobs across print, TV, and digital newsrooms in just six months. This trend is expected to continue, with experts predicting ongoing restructuring and cost-cutting in the Indian media industry. There are apprehensions that layoffs in India may persist in 2025, though at a slower pace than in 2024.

Many legacy media, particularly small and medium print outlets have been forced to close publication. The high cost of printing, diminishing circulation and decline in advertisement revenue are the main reasons for such closures. Some of the influential regional newspapers published for many years have had to down their shutters. For example, Nagaland Page, an English daily published from Dimapur of Nagaland state which was founded in 1999 ceased publication in 2024. Sadin and Asam Bani, two influential weeklies published from the two largest media houses of Assam were made supplements of their main daily publications. Closure of a newspaper entailed retrenchment and the difficulty of finding a job within the same regional media market.

Way forward

As news consumption shifts online and automation increases, the media landscape is undergoing significant transformation. It is important for journalists and audiences alike to consider the changing contours of human-produced news including the impact of precarious employment and working conditions and the implications of these changes on public life and the democratic ethos. The media must strengthen its capacity to approach the judiciary to uphold its watchdog role. At this crucial juncture, the media community must stand united to defend press freedom and form critical alliances with civil society and lawyers ready to defend its rights as a pillar of democracy.