PAKISTAN

Steady Erosion

The passage of the Prevention of Electronic Crimes (Amendment) Act in January 2025 sparked a bitter dispute between the state and media. While the federal government championed the legislation as a vital step in combating fake news, critics decried it as “draconian” and detrimental to free speech. A journalist protests the PECA amendments in Islamabad on January 28, 2025. Credit: Aamir Qureshi / AFP

Dwindling spaces for free expression and the rapid unravelling of the traditional model of the media economy have left Pakistan’s media sector battling for survival. In the period under review, apart from worsening conditions of safety and job security for journalists and shrinking margins for independent journalism, the media faces significant challenges in both professionalism and economic viability, reflecting the broader decline in democratic spaces and political freedoms.

In steep contrast to its well-documented press freedom woes, a digital communications revolution is also underway within the country’s vibrant and growing digital sector. While more outlets are rapidly emerging, these are largely unregulated, with many mainly serving personal business interests – bringing their own set of complications. Given the stagnation in legacy media, some of the country’s most renowned journalists have also moved toward creating their own online platforms. Whilst the country may have one among ten of the most digitalized societies in the world, it remains beset by restrictive policies on free speech and accessibility that – even in the digital space – stymie its potential to be an optimally flourishing digital media community, including the media, the telecom and internet sectors.

More broadly, the mainstream media in Pakistan is characterised by falling professional standards, inadequate diversity in media leadership, the absence of economic sustainability in terms of revenue diversification, and a dearth of skills and resources needed for media practitioners to navigate the rapid digital transformation of the industry. Without urgent and scaled-up strategic interventions, the ability of Pakistani media to serve as a pillar of democracy and accountability, particularly in the face of the state’s determination to expand restrictions on free speech, will continue to erode.

Policing cyberspace

In the period under review, Pakistan faced severe setbacks to freedom of expression and access to information online. Several measures taken against journalists and activists posed significant threats to free speech, public interest journalism, and safety of media organisations.

The passage of the Prevention of Electronic Crimes (Amendment) Act, 2025 in January sparked a bitter dispute between the state and media practitioners. While the federal government championed the legislation as a vital step in combating fake news, critics decried it as “draconian” and detrimental to free speech. With its vague definitions of false information, the legislation criminalised the dissemination of purportedly inaccurate information, with offenders facing possible jail time of up to three years. The law expanded the scope of what could be deemed unlawful, established the Social Media Protection and Regulatory Authority — a federal body empowered to levy fines up to PKR 2 million (USD 7,000) on online content — and introduced a new grievances redressal mechanism. Notably, the law mandates that appeals must be filed directly with the Supreme Court, bypassing High Courts. It also redefined provisions to allow third party legal entities to lodge complaints with the FIA, raising concerns that this could be used to suppress dissent and silence critics.

A joint statement by the IFJ and its affiliate, the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ), demanded the immediate repeal of the amendments, and held protests to protect freedom of expression. Pakistan’s Joint Action Committee said in a statement that the focus of the new bill “is not just social media but also electronic and print media’s digital platforms, with the aim of criminalising dissenting opinions” and accused the government of “breaching” its promise by passing the bill without consulting media stakeholders.

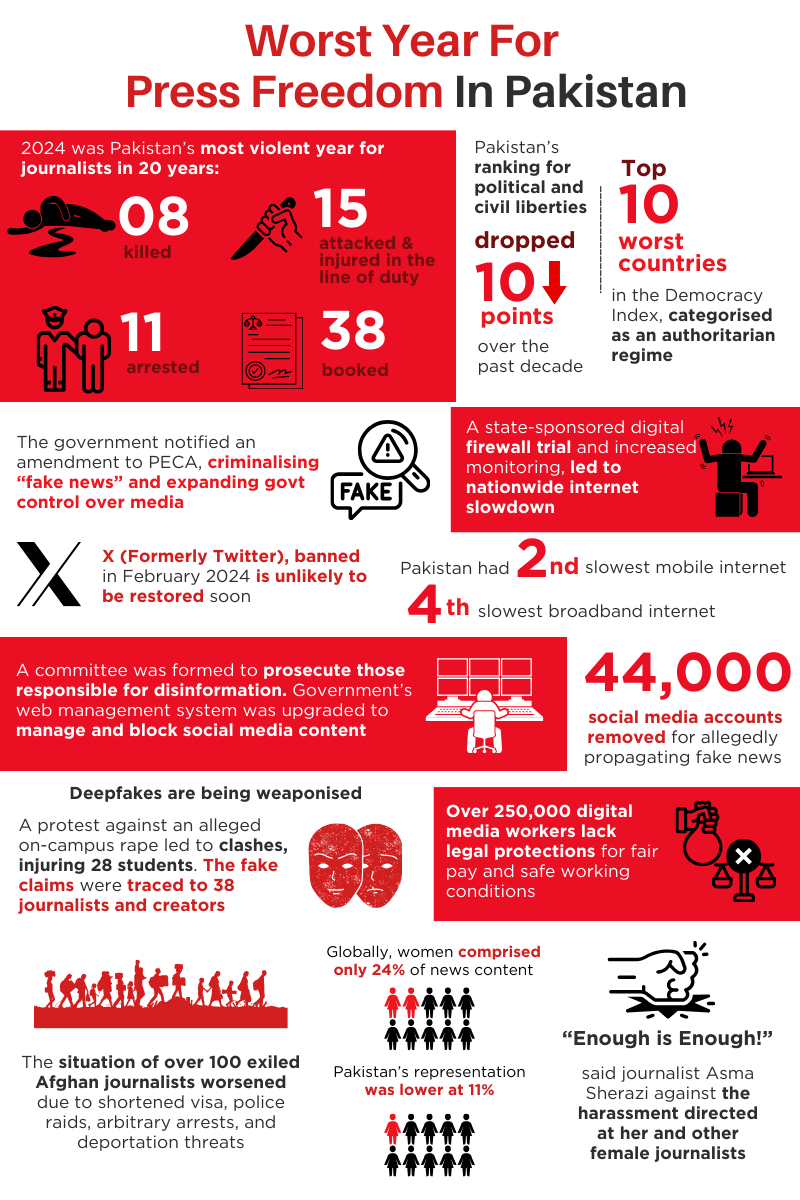

In 2024, Pakistan was ranked in the Speedtest Global Index as the second lowest globally for mobile internet, and at 148 out of 151 countries for broadband speeds. A state-sponsored digital firewall trial in July 2024, and increased government monitoring, led to nationwide slowdowns troubling the public and media. In August 2024, the Wireless and Internet Service Providers Association of Pakistan blamed the increased monitoring of internet traffic for a nationwide slowdown of online services. Telecom operators warned of potential financial losses. Internet and telecom regulator, the Pakistan Telecom Authority (PTA), blamed undersea cable faults. By November 2024, it announced the restoration of these cables, aiming to resolve the bandwidth issues.

In September 2024, a report in The News warned that intentional internet shutdowns and disruptions and widespread online surveillance were a threat to Pakistan’s digital landscape and democratic freedoms. Enlightened Offenders, Endangered Communities: Internet Shutdowns in 2024, a report by digital rights organisation Access Now, named Pakistan among the top three offenders in Internet shutdowns. Pakistan, with 21 shutdowns — the highest number ever for the country — ranked third after Myanmar and India. Describing the harms of internet shutdowns, the report said that behind each shutdown is the “story of people and communities cut off from the world and each other. Their stories make it clear: even one shutdown is one too many.”

Media Rights Violations

Killings

Arrests

Without urgent and scaled-up strategic interventions, the ability of Pakistani media to serve as a pillar of democracy and accountability, particularly in the face of the state’s determination to expand restrictions on free speech, will continue to erode.

Under the strong arm of military control and its dominance over the country’s political sphere, Pakistan is for all intents and purposes an authoritarian regime operating under the guise of democracy. A vendor sells Pakistan’s national flags ahead of the country’s Independence Day in Islamabad on August 12, 2024. Credit: Aamir Qureshi / AFP

Blocks and bans

February 2025 marked one year since a ban was imposed on social media platform X by the Pakistani government. Currently the platform is accessible only through use of a Virtual Private Network (VPN). While the government held that the platform was blocked for reasons of “national security”, the ban notably came into effect shortly after the polls in Pakistan’s February 2024 elections, as allegations of vote rigging erupted online. At the same time, opposition parties, political observers, the media and the public were also expressing doubts about the fairness of the electoral process. Soon after the results were out, one senior bureaucrat, acting as a whistle blower, publicly admitted his role in rigging the elections.

Critics of the X ban have approached the courts on the matter and are continuing calls for its restoration. In a positive development on March 20, 2025, the Lahore High Court gave the government a last chance to explain its stand on the ban. While the ban on X was in place, other social media platforms such as YouTube, Meta and WhatsApp continued to be spaces for public debate and dissent. Attempts to control these spaces were ongoing in the period under review.

The federal government, in July 2024, formed a five-member Joint Investigation Committee tasked with identifying and prosecuting those responsible for disinformation and “disruptive” social media campaigns. Digital rights advocates, however, criticised the investigative approach, warning that reliance on criminal rather than civil law amounted to a direct attack on free speech. They cautioned that this strategy would only deepen the rift between the state and its citizens, further eroding public trust.

In August 2024, the Pakistan Telecommunications Authority (PTA) confirmed that the government’s web management system was being upgraded to manage and block social media content. Amnesty International urged authorities to ensure greater transparency in the deployment of online surveillance technologies. In August, the Asia Internet Coalition warned that Pakistan’s proposed data localisation policies could negatively impact its digital economy.

In September, the PTA reported the removal of over 44,000 social media accounts, including those of some journalists, for allegedly propagating fake news, including 61 posts published by the official handles of political parties.

Government funding and economic impacts

The period under review was characterised by a continuing unravelling of the media economy, negatively impacting journalism jobs and revenue streams for media establishments and operations.

Government-issued advertisements continued to be a major revenue spinner for Pakistan’s media industry in 2024. In July 2024, the Senate was informed that the government had allocated PKR 16 billion (USD 58.2 million) in advertisements over the past five years. Of this, PKR 9 billion (USD 32 million) went to print media and PKR 6 billion (USD 21.8 million) to electronic media. Government advertisements have long been used as leverage to buy compliance, and critical media outlets have been denied this source of revenue. The Dawn Media Group, one of the oldest in the country, had been facing an apparent unofficial ban on advertisements in retaliation for its independent editorial line. Media watchdog Freedom Network on April 10, 2025, called for the setting up of an Independent Steering Committee to allot government advertisements to the media in an unbiased manner.

The media landscape continued to be marked by uncertainty, as journalists and media workers grappled with a lack of legal protections, and mounting threats to their livelihoods. In September 2024, according to a legal brief furnished in the Islamabad High Court by the Institute for Research, Advocacy, and Development (IRADA), with IFJ’s support, over 250,000 digital media workers lacked legal protections concerning fair pay and safe working conditions. The report bemoaned the government’s failure to reform labour laws in the realm of digital journalism, leaving workers without protections afforded to print media employees.

In October 2024, the Information Minister of Punjab province casually threatened journalists with job losses if they “disrupted” a press conference scheduled by current Chief Minister Punjab drawing condemnation from media professionals who accused her of stifling free speech by threatening job security.

In February 2025, pensioners of the state-owned Pakistan Television (PTV) protested across Pakistan, demanding long-delayed pension payments and the restoration of medical benefits on credit.

Some provincial government-backed initiatives provided crucial tangible support to Pakistan’s embattled journalism community during the reported period. In October 2024, Balochistan doubled the Working Journalists Welfare Fund to USD 1.8 million and allocated USD 725,000 for the Quetta Press Club. In January 2025, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa issued a USD 180,000 grant to the Peshawar Press Club and raised the provincial Journalists Welfare Endowment Fund to USD 725,000. In March 2025, Punjab doubled the endowment of its Journalist Support Fund to USD 360,000 and promised subsidised healthcare for journalists.

Rising taxation is also affecting Pakistan’s press sector, increasingly weighed down by dwindling sales and financial strain. The Federal Budget 2024-25, presented in June, sparked concern within the All Pakistan Newspapers Society (APNS), which decried escalating production costs — exacerbated by a depreciating rupee — that were pushing the sector to the brink. The imposition of a general sales tax on imported newsprint, coupled with a 25 per cent reduction in tax exemption on advertising expenses, was met with fierce opposition, with media owners warning that such measures could cripple the industry. This step was later reversed following protests.

Pakistani media also faced the worst scenario for the industry with large scale retrenchments, closure of editions of print media of some of the leading media groups like Jang London’s edition, Karachi’s edition of Dunya and 92, while some of the country’s television channels have also shifted their main bureaus to one station leaving the workers of other stations also under threat to lose their jobs. Besides this, a number of television anchors of the mainstream media who were taken off air and prevented from hosting their shows, could not appear on other channels either. The latest in the list are ARY’s prominent anchor, Kashif Abbasi, SUNO TV anchors, Habib Akram and Paras Jehanzeb and recently, prominent journalist Imtiaz Gul claimed that he has been stopped from appearing on talk shows.

With the estimated 250,000 digital media employees in Pakistan lacking effective legal protections for their rights at work, including fair pay, a legal brief submitted to the Islamabad High Court in September 2024 highlighted gaps in the legal framework for media workers’ rights. Submitted by IRADA, in a case at the court triggered by a letter by IFJ, the brief recommends legal protections against at-will termination; obligatory employer contributions to welfare schemes’ compulsory provision of gratuity, provident fund, and insurance; and penalties for delayed or unpaid wages. A 2024 report by the Digital Media Alliance of Pakistan, found the sector to be unstable and informal, with many young workers facing volunteer, unpaid, or insecure labour conditions.

In September, the PTA reported the removal of over 44,000 social media accounts, including those of some journalists, for allegedly propagating fake news, including 61 posts published by the official handles of political parties.

With media literacy limited in Pakistan, deepfakes are regularly weaponised, damaging the reputations of particularly women politicians, often through sexually explicit fabrications. Azma Bukhari, Information Minister of Pakistan’s province of Punjab, speaks with media after attending her deepfake video case hearing in Lahore on November 20, 2024. Credit: Murtaz Ali / AFP

AI in the newsroom

Anecdotal evidence suggests that many newsrooms in Pakistan are starting to employ AI in their professional functions, but research or formal documentary evidence is scarce in terms of the nature and scale of this shift, as well as the impact on traditional job markets within the media industry. However, digital journalism practices by informal media, including social media operations and some media start-ups, are being seen as taking undue liberties in the use of AI.

In Pakistan, where media literacy remains limited, deepfakes — manipulated audio, images, and videos — are being weaponised, both intentionally and otherwise. These deepfakes have been used to damage the reputations of particularly women politicians, often through sexually explicit fabrications. This form of disinformation not only reinforces obstacles to women’s advancement in politics and public spheres but also puts a question mark on public perception of digital journalism. In July 2024, following the circulation of an offensive deepfake video targeting Punjab’s Information Minister, fellow female lawmakers vowed to take legal action against the perpetrators. The video was swiftly debunked by fact-checking platform iVerify.

In February 2025, the police filed three cases under the PECA law, accusing individuals of spreading AI-generated deepfakes of Punjab Chief Minister, propagating disinformation, and targeting women politicians. The Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) later claimed to have traced over 20 social media accounts at the core of the distribution network.

Disinformation without borders

The unchecked proliferation of disinformation in Pakistan continues to negatively affect public discourse, triggering consequences that sometimes extend beyond borders. In July 2024, a tragic incident unfolded in Southport, United Kingdom, where three young girls were killed in a brutal attack at a dance event, only for false claims to circulate on social media portraying the male suspect as an Islamist migrant. This disinformation ignited violent anti-Muslim and anti-migrant riots across the UK. In August 2024, authorities in Lahore arrested Farhan Asif, a Pakistani national accused of amplifying the narrative, which had even deceived major media outlets such as the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) into believing the fabricated news story was orchestrated by a coordinated team.

In the period under review, there also emerged some instances of online disinformation triggering social unrest. In October 2024, 28 students were injured during violent clashes with the police in Lahore, ignited by a protest against an alleged on-campus rape. But as the episode unfolded, authorities uncovered a web of disinformation leading to the registration of a fake news case. The FIA traced the origins of the alleged false claims to 38 journalists and digital media content creators who had reportedly amplified the fabricated narrative, stoking further unrest. In the same month, a seven-member inquiry committee submitted its findings to the Punjab government, affirming that no rape had occurred and that the protests had been fuelled entirely by misleading information propagated online. The episode not only adversely impacted genuine cases of harassment and assault but also underscored unchecked proliferation of unverified content across both digital and traditional media, driven either by a lack of rigorous fact-checking or reportedly by non-professional political, financial, or social agendas.

In the line of fire

The period under review was the most violent for journalists in Pakistan in two decades. At least eight journalists were killed: Kamran Dawar, Khalil Jibran, Hasan Zaib, and Janan Hussain were killed in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province; Ashfaque Ahmed Sial, and Zafar Iqbal Naich) were killed in Punjab; and Nasrullah Gadani, and Bachal Ghunio were killed in Sindh. At least 15 journalists were attacked and injured in the line of duty, and 11 journalists were arrested. Multiple media establishments were attacked, including a press club and some offices of television channels. The abduction of Asif Karim Khehtran in Balochistan, and the brothers of exiled journalist Ahmad Noorani (possibly by intelligence personnel), was an ongoing form of intimidation.

Legal cases were instituted against at least 38 journalists. Farhan Mallick, who runs a YouTube channel Raftar, was arrested under the amended PECA Act on March 20, 2025, and handed over to the FIA, for allegedly airing “anti-state” content on his channel. He was released on bail on April 8.

Prominent women journalists, including Asma Shirazi, Munizae Jahangir, and Gharida Farooqi, faced intense harassment and threats in the period. In July 2024, the Network of Women Journalists for Digital Rights issued a statement, supported by over 60 media practitioners, denouncing derogatory and sexist remarks made by a social media influencer towards Farooqui in a viral video. It described the online vlog as “extremely triggering with the use of graphic language against women journalists in the country” and condemned the spread of inappropriate language targeting women across digital platforms.

The situation of over 100 exiled Afghan journalists in Pakistan further deteriorated during the period under review. Shortened visa durations and an increase in police raids exacerbated the harassment, arbitrary arrests, and deportation threats faced by these media professionals struggling to survive with the country.

A small but significant intervention to improve journalists’ safety took place in November 2024. The IFJ and PFUJ hosted training workshops in Punjab province in which over 200 rural and regional media workers from diverse backgrounds were trained on their “rights at work”. In a participatory learning environment, attendees shared recurring themes of inadequate wages, insecure work, lack of unionisation among digital and freelance journalists, and the need for improved and enforced workplace protections. The training provided key insights into legal remedies and rights for regional correspondents and freelance journalists.

Another positive development was the enforcement of the Protection of Journalists and Other Media Practitioners, Act 2021 in Sindh, where the Provincial Assembly took the lead not only in forming the Journalists Protection Commission, but in February 2025 set up its Secretariat, which was expected to be fully functional within a month. A key step forward is the decision of the Commission to issue letters to all the media employers to ensure life insurance and safety training under the Sindh Protection Journalists Act, 2021. Unfortunately, such Commissions have not been set up at the federal level or in other provinces, showing a lack of seriousness in its implementation. In fact, other than Sindh, no province has any legislation in place for journalists’ safety.

Deepfakes have been used to damage the reputations of particularly women politicians, often through sexually explicit fabrications.

The period under review was the most violent for journalists in Pakistan in two decades.

Pakistan faced severe setbacks to freedom of expression and access to information online. Several measures taken against journalists and activists posed significant threats to free speech, public interest journalism, and safety of media organisations. Members of the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ) march in Karachi on World Press Freedom Day on May 3, 2024. Credit: PFUJ

Breaking new ground

In terms of financial viability of digital media, some sections of Pakistani digital creators did well for themselves by substantially increasing both earnings and viewership. In 2024, the number of Pakistan-based YouTube creators earning over PKR 10 million (USD 36,000) annually surged by 25 per cent, while over 65 per cent of views of Pakistani content came from abroad. Google’s 2024 Year in Search list confirmed this shift, with slice-of-life content emerging as the most popular genre for audiences in the country.

Despite this growth, censorship persisted. In the period under review, removal of content by social media platforms intensified as part of efforts to enforce community guidelines. In 2024, TikTok removed over 50 million videos posted from Pakistan.

Pakistan’s 2024 national elections saw a significant shift towards digital campaigning and electoral administration. Political parties used social media and digital platforms extensively to connect with voters, complementing traditional rallies with virtual gatherings. However, the use of digital technology and social media for campaigning led to increased polarisation in political discourse.

Post-election, social media was rife with disinformation and hate speech, especially from parties rejecting the election results. The government responded with measures such as a ban on media platforms, suspension or degradation of internet services, and prosecution of political activists and journalists. The curbs on media and the crackdown on digital expression stifled free speech and dissent, impacting democratic principles, while legal battles and social unrest increased from perceived injustices and restrictions on digital freedoms.

Democratic deficit

In 2024, global freedom declined for the 19th consecutive year, with 60 countries experiencing deterioration in political rights and civil liberties, while only 34 countries saw improvements. Pakistan was ranked “partly free” by Freedom House in its annual report released in February 2025, declining three points from 2023 and 10 points over the past decade. Key factors contributing to the decline included violence and repression around elections, ongoing armed conflicts, and the spread of authoritarian practices, including restrictions on freedom of expression, and curbs on access to information.

Pakistan’s democracy ranking fell by six spots in 2024, with the country listed among the top 10 worst performers in the Democracy Index by the Economist Group’s Intelligence Unit. Pakistan was ranked 124th globally and categorised as an authoritarian regime. The report said that elections in Pakistan and other South Asian countries in 2024 had been marred by fraud and violence, with allegations of political repression and interference by authorities in Pakistan’s general election.

In 2024, the number of Pakistan-based YouTube creators earning over PKR 10 million (USD 36,000) annually surged by 25 per cent.

In the period under review, there were various instances of online disinformation triggering social unrest. In October 2024, 28 students were injured in clashes with police during a Lahore protest over an alleged campus rape. Authorities later uncovered a disinformation campaign and filed a fake news case against 38 journalists and digital creators for spreading the false narrative. Female police personnel stand guard beside a wall handprinted by the rape protesters. Credit: Arif Ali / AFP

‘Enough is enough’

Women journalists continued to face persistent harassment in 2024, often at the hands of political figures and the country’s vast network of social media users. The targeted abuse ranged from verbal assaults to coordinated digital campaigns, fuelled by women journalists’ professional critiques and positions on sensitive issues. In September 2024, anchor Gharida Farooqui initiated legal proceedings against the Chief Minister of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa for making baseless accusations against her during a speech at a public rally.

In January 2025, journalist Asma Sherazi denounced a campaign of harassment directed at her and other female journalists, declaring “enough is enough”. Media rallied behind a petition from the Digital Rights Foundation calling for an end to the systematic harassment orchestrated against media professionals by political factions and their supporters. In February 2025, there was condemnation of a hate campaign targeting journalist Munizae Jehangir across various social media platforms.

Despite existing laws and societal condemnation, misogyny continued to thrive across social media, current affairs talk shows, podcasts, and national television in the period under review. In its October 2024 report to the UNHRC regarding human rights concerns and Pakistan’s commitments under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Amnesty International recommended “the effective implementation of laws aimed at tackling technology-facilitated gender-based violence through gender sensitive reforms in the judicial system”.

Gender representation in media continued to be skewed, as evidenced by a study by the Uks Research Center, unveiled in October 2024. Analysing the 2024 election coverage cycle, the study found a greater prevalence of female anchors over reporters in electronic media, alongside a noticeable scarcity of women reporters in both English and Urdu print outlets. Other concerns included the dominance of personality-driven narratives focused exclusively on prominent women politicians, while issues impacting women and women candidates were largely neglected.

Supported by IFJ, a major gender mapping project across five regions of Pakistan by the Women’s Media Forum Pakistan in early 2025 assessed 15 media companies across Islamabad, Punjab, Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan. The results highlighted stark disparities, revealing that fewer than ten journalists were employed in Balochistan. However women journalists constituted up to 35 per cent of union members in larger urban centres, including Karachi and Lahore. Geo News, while promoting a gender positive message, employed only 10 per cent of women journalists in Peshawar, and only 10 of 125 of its employees in Islamabad. Aaj News Peshawar’s mapping found only 3 per cent of overall staff were women, while ARY News employed just nine women out of a workforce of 150 in Sindh, with minimal representation of women in decision-making roles. Lahore’s Neo News had just 67 women among 853 employees, and Samaa News employed 91 women out of 1,197. The Karachi-based Jang Group had employed 16 women, compared to 105 men.

In February 2025, at a conference organised by the Centre for Peace and Development Initiatives in collaboration with National Commission on the Status of Women and the European Union (EU), data revealed that globally women comprised only 24 per cent of news content. Pakistan’s representation was even lower at 11 per cent. Participants advocated for reforms, including equitable inclusion and a broader movement for gender parity within Pakistani media.

Yet, women in the media are continuing to make their mark despite the obstacles. A 2025 IRADA report, ‘Beyond the Bylines’, chronicled the life stories of nine women journalists working in regions across Pakistan plagued with deep-rooted gender inequality. Despite enduring professional harassment and societal constraints, these women were amplifying marginalised voices and challenging patriarchal norms within media. The report called for the creation of a more inclusive media landscape, one where women media practitioners are free from the threat of censorship and bias.

In January 2025, journalist Asma Sherazi denounced a campaign of harassment directed at her and other female journalists, declaring “enough is enough”.

Prominent women journalists, including Asma Shirazi, Munizae Jahangir, and Gharida Farooqi, faced intense harassment and threats in the period. In July 2024, the Network of Women Journalists for Digital Rights issued a statement, supported by over 60 media practitioners, denouncing derogatory and sexist remarks made by a social media influencer towards Farooqui in a viral video. Credit: Instagram

Legal knots

In May 2024, the Punjab Assembly enacted the new Punjab Defamation Act, 2024. It vaguely defined defamation, allowing it to be adjudicated “without proof of actual damage or loss”, and making it punishable by fines of up to PKR 3 million (USD 10,000). The law creates special tribunals, with adjudicators appointed after consulting with the Chief Justice of the Lahore High Court. These tribunals can compel offenders to issue an “unconditional apology”, and direct regulatory bodies to block their social media accounts and other platforms used to disseminate defamatory content.

Following its enactment, the Joint Action Committee, comprised of various media bodies, decried its regulatory nature, describing it as “draconian in its current form, threatening the fundamental right to freedom of expression”. Opposition parties echoed this sentiment, with Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) distancing itself from the legislation and the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf’s National Assembly opposition leader, denouncing it as “oppressive and tyrannical”. In September, the PFUJ challenged the law’s constitutionality, prompting the court to instruct provincial authorities to respond.

As outlined, the passing of the PECA amendments in January 2025 was met with widespread condemnation from media, civil society, stakeholders and rights groups to this development which was viewed as undeclared censorship. The government’s apparent intention for the law was to push forward a new Social Media Protection and Regulatory Authority empowered to order blocking of “unlawful or offensive online content” targeting the judiciary, the armed forces, parliament, provincial assemblies, or material that promotes and encourages terrorism and other forms of violence against the state or its institutions. But opponents said the law would criminalise ‘fake news’, restrict online freedom of expression, and expand government control over social media platforms and conventional media.

In February 2025, a wave of protests erupted as media rights groups rallied against the legislation. During her visit to Pakistan, IFJ President Dominique Pradalie backed media opposition to recent amendments to the national cybercrime law that curbs freedom of expression. Pradalie led a PFUJ protest march in Islamabad and addressed a seminar, attended by opposition political parties, against the controversial amendments to the PECA law, urging Pakistani authorities to uphold freedom of expression, repeal PECA, and provide urgent support for the media community. The IFJ has declared PECA as a “black law”, resolved to launch a global campaign, and to appeal to the UN if it was not withdrawn.

The PFUJ also spearheaded hunger strikes and protests across the country, with journalists rallying against the amendments and denouncing the changes as tantamount to “martial law for media”. These protests culminated in a united call for a “joint struggle” against the amendments, with journalist organizations, the legal community, and human rights advocates joining forces. In response to the backlash, a parliamentary panel set up a sub-committee to liaise with both journalists and the federal government to address grievances. The PECA Act also faced a wave of legal challenges in the country’s highest courts, with petitions filed in the Supreme Court and four of the five High Courts – Islamabad, Balochistan, Lahore, and Sindh.

In May 2024, the Punjab Assembly enacted the new Punjab Defamation Act, 2024. It vaguely defined defamation, allowing it to be adjudicated “without proof of actual damage or loss”.

Legal cases were instituted against at least 38 journalists. Farhan Mallick, who runs a YouTube channel Raftar, was arrested under the amended PECA Act on March 20, 2025, for allegedly airing “anti-state” content on his channel. Mallick hugs a friend after getting released on bail at his home in Karachi on April 7, 2025. Credit: Asif HASSAN / AFP

Towards diversity

Pakistan’s media industry has a workforce that faces exploitation and hazardous conditions due to a lack of effective or enforced labour rights legislation. New research to be unveiled in May 2025, conducted by IRADA in collaboration with FES Pakistan and IFJ, stresses the need for strengthened labour movements and their efficacy. The report, ‘Modernising Journalists’ Trade Unions in Pakistan in the Digital Age’, was developed after consultations in Islamabad, Karachi, Lahore, Quetta and Peshawar with union leaders from all factions of PFUJ and regional unions discussed issues such as exclusion, undemocratic practices, financial instability, aggressive union-busting tactics by media houses, corporate interference, and the shrinking space for independent journalism.

Recommendations included: more inclusive unions that actively welcome women, young members, and journalists from the freelance and digital sectors – which are also the highest areas of media growth in the country; modernised structures in their unions, stronger financial management and transparency; and improved legal registration of actual media unions to strengthen their legislative impact.

A study mapping representation of women in journalists’ unions and press clubs in Pakistan’s ten largest cities, conducted by Women Journalists Association (WJA) and Freedom Network with International Media Support (IMS) in early 2025 revealed grim results. The data showed that the participation of women journalists in press clubs remained limited, with only two press clubs (Lahore and Islamabad) reporting slightly more than 10 per cent share of women in their member rolls. Lahore Press Club leads all the other press clubs in terms of absolute number of women members, with 300 women journalists among its 2,970 members followed by National Press Club Islamabad (3,346 total, 250 women). Among large press clubs, the Gujranwala Press Club has no women members.

A welcome change was seen in the inclusion of more women in the PFUJ. Among unions, Punjab Union of Journalists leads with the highest absolute number of women union members (300) followed by Karachi Union of Journalists with 125 women union members out of a total of 1,800. These unions, and the Rawalpindi-Islamabad Union of Journalists were the only journalist trade union in the sample that reported inclusion of women in their elected cabinets. Moreover, for the first time, ten women leaders were elected across the new Federal Executive Council of the PFUJ.

Collaboration and solidarity

In November 2024, the Standing Committee on Information and Broadcasting of Pakistan’s National Assembly formed a sub-committee to address the issue of unpaid salaries for media workers. The committee is charged with evaluating the status of salary payments and outstanding dues and recommend measures to safeguard the rights of media workers.

At the outset, the committee expressed serious concern over the financial practices of certain media houses and directed the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (PEMRA) and the Implementation Tribunal for Newspaper Employees to ensure the timely disbursement of salaries, and adherence to contractual obligations. It also proposed stricter regulations to protect media workers’ rights.

As well as the nationwide protest to the cybercrime law PECA in early 2025, there were other noted solidarity actions in Pakistan around perceived threat to press freedom. A coalition was formed to protect freedom of expression, including organisations such as the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), PFUJ, the Supreme Court Bar Association, and the Digital Media Alliance for Pakistan. The decision came at a consultation held by the HRCP, which criticised the amendments for stifling freedom of expression for both the press and ordinary social media users.

In February 2025, a national consultative meeting of lawyers and journalists, convened by the Supreme Court Bar Association and attended by journalists’ bodies, political parties and civil society organisations, adopted a joint resolution calling for the immediate repeal of the PECA amendments, citing violations of Article 19 of the Constitution of Pakistan guaranteeing freedom of expression and international covenants.

As with the overall democratic space and political freedoms in the period under review, the Pakistani media landscape also recorded slides in the margins for its professionalisms and viability this year.

The need for better organised and scaled-up efforts to support solidarity within media, and with stakeholders invested in freedom of expression and public interest journalism, is greater than ever. Of particular importance are continued efforts to strengthen media professionalism, solidarity among journalists, diversity in media leadership, diversification of media economy, and support for media practitioners to ably navigate and benefit from the rapid digitalisation of the media sector.

PFUJ and regional unions discussed issues such as exclusion, undemocratic practices, financial instability, aggressive union-busting tactics by media houses, corporate interference, and the shrinking space for independent journalism.

In November 2024, the Standing Committee on Information and Broadcasting of Pakistan’s National Assembly formed a sub-committee to address the issue of unpaid salaries for media workers.

Feminist activists take part in the ‘Aurat March’ or women’s march to mark Pakistan’s National Women’s Day, in Lahore on February 12, 2025. Credit: Arif Ali / AFP