India

An Untraced Murder in Kashmir

06 May, 2015

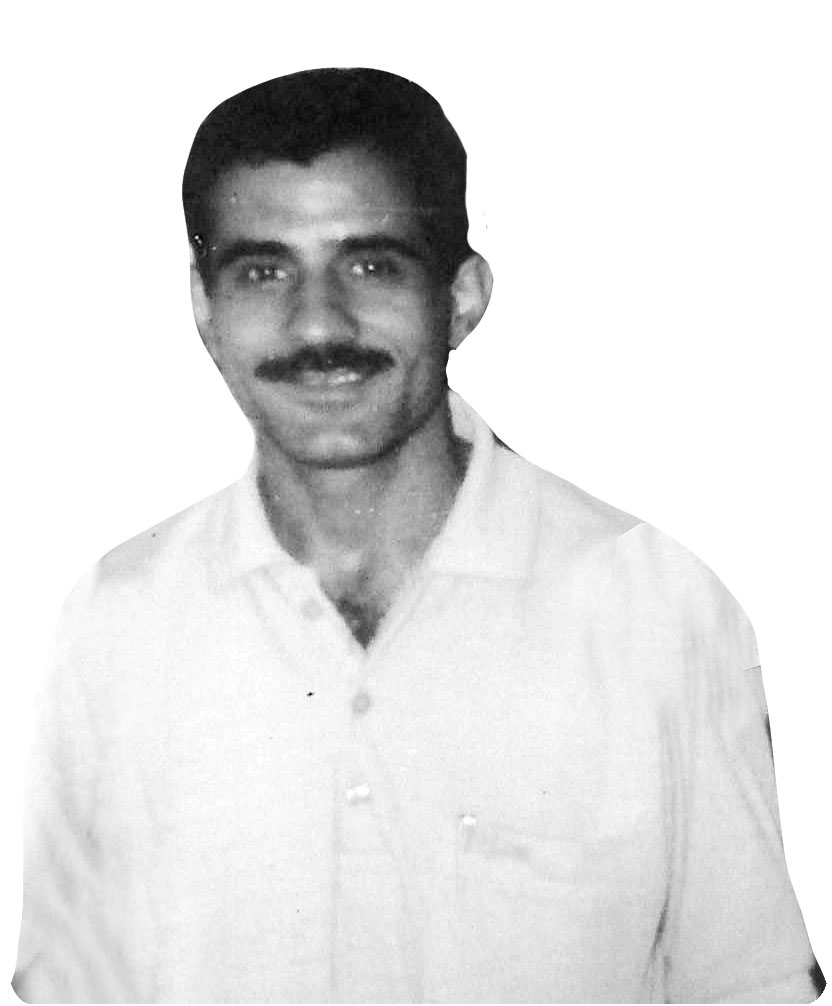

On a chilly evening Parvaz Mohammad Sultan was giving final touches to his daily bulletin when two unidentified gunmen entered his press enclave office and fired at him from point blank. Left in a pool of blood, the 40-year-old editor of local news gathering agency News and Feature Alliance (NAFA), was shifted to hospital but he lost the battle with his life on the way. Parvaz was not the first journalist killed during the conflict in Jammu and Kashmir, but he left a trail of misery behind him with a young wife and three small children.

Parvaz hailed from a remote village of Khiram in south Kashmir. A talented guy, he tried his hand in writing and soon carved a space for him in the vernacular press. He worked in Al Safa, and then a leading Urdu daily published from Srinagar and also wrote analytical pieces for Urdu weekly Chattan.

Parvaz had also a stint as a reporter with Congress mouthpiece Quami Awaz, published from Delhi. However, in 2000 he launched his own news service to give fillip to feature writing and received an encouraging response from the readers and news organisations. He also edited a local newspaper Wattan, though unofficially. It was owned by the infamous counter-insurgent turned legislator Javed Shah, who was also killed by militants in 2003.

The motive behind Parvaz’s killing continues to remain a mystery, as has been the case with hundreds of killings added to the accounts of “unidentified” gun men. This is true with the killing of 10 other journalists as well who fell to the bullets or blasts since the outbreak of armed rebellion in Kashmir in 1989. However, the grapevine is that Parvaz’s death was connected to the intergroup rivalry within a prominent militant organization. One version, not verified by independent sources, is that he “was used by one faction”, thus inviting trouble from the other. But his association with the newspaper owned by the counterinsurgent can also not be ruled out as a provocation for his murder.

Like many other cases, this was also a “blind” case for police, who hardly bothered to go deep into the conspiracy and identify the killers. While a case was registered in Police Station Kothibagh (Srinagar) on January 31, 2003, under FIR no 13/2003, the police investigation has failed to identify the attackers and has not been expanded to a desired limit.

According to officials, who wished not to be named, the case has been closed as “untraced” in 2003 itself. “Untraced means we could not identify the attackers and could not reach to them so the case was almost closed,” an official said. However, the police has mentioned that it was the handiwork of “militants”.

The then-Superintendent of Police Srinagar has also given a “clean chit” to Parvaz, saying “he had no connection with any militant or anti-national organization”.

With the militant link to the killing becoming apparent, the journalist fraternity in Srinagar also turned its back on the issue. There was no follow up to the case except the statements from the organizations such as International Federation of Journalists, Committee to Protect Journalists and Reporters Sans Frontiers who expressed their concern and demanded independent probe into the killing.

For the shattered family of Parvaz, survival was more important than following the case to get justice. His 29-year-old wife Shameema was a broken soul who mustered courage to get a government job as compensation to her husband’s death. She needed the job to grapple with the challenge of bringing up three small children and ensure their education. But there was more trouble in store for the hapless family. Severely affected by the shock of her husband’s death Shameema’s health deteriorated and she finally passed away just after doing the job for 18 months. This literally dismembered the family leaving the three children Sheema (11), Junaid (6) and Umar (3) at God’s mercy. There was nothing for them to fall back upon except an aging grandmother and an aunt (father’s sister) who was already married.

The arduous task to take care of three orphans was left to Parvaz’s mother Rehmati (75). She ran from pillar to post to see that the children do not die of hunger. From Deputy Commissioner’s office to Social Welfare Department, she managed to get a meagre amount in the name of being a widow and tried to feed the children who are now in their teens.

“This has been the biggest challenge God threw upon me,” Rehmati says with tears rolling down her wrinkled cheeks. “First Parvaz’s father passed away in young age and now I have to take care of these grandchildren. Can misery be worse than this?” she asks.

With the help of some journalists and philanthropists she is managing to bring them up and give them education. For her to pursue the case against the killers has no meaning. “What will I get even if they are hanged?” she says. “I only want safe future for these three young children” adds Rehmati.

Ironically there is no welfare scheme for journalists and their families in the state. And the way the fraternity has ignored the sufferings of such families; it is difficult to see a better future for the sufferers.

It is worth mentioning that Parvaz’s name figures among hundreds of journalists whose pictures are hanging as “heroes of freedom of press” at the Washington based Newseum. But will such honors get the family out of the trauma and secure them the justice? The question is indeed difficult to answer.

Shujaat Bukhari is a senior journalist based in Srinagar. He is editor of Rising Kashmir. Previously he worked as bureau chief of The Hindu for 15 years.

This is an edited version of a piece from Rising Kashmir on May 6, 2015

Written By

Comments

Resources

- IFJ South Asia Media Bulletin, February 2023 02/15/2023 Download

- IFJ South Asia Media Bulletin, January 2023 01/18/2023 Download

- Nepal Press Freedom report 2022 01/03/2023 Download