SAMSN Blog

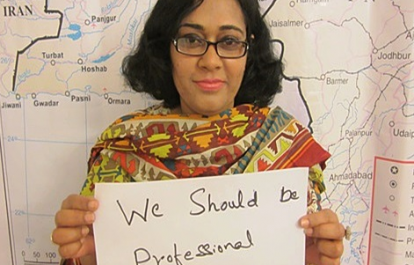

The challenges of a female reporter in Pakistan

24 Jul, 2014

The horrible morning of Sunday, November 22, 2013, the Christian community of Peshawar was targeted by two consecutive suicide blasts at the All Saints Church Kohati, Peshawar.

I arrived there within 10 minutes of the incident. The scene in the church was very horrible. The walls and floor were coloured with human blood. Body pieces of victims were scattered within the church premises – men, women, elders and children were among them. Being a mother, I almost fainted when I saw the body pieces of little angels.

There was no space on the floor without blood to take a step. I was lined up to broadcast live by my TV channel and the beeps started. I was talking with the wounded, the families of victims, officials and community representatives, all live from the blast scene. This live transmission at the scene continued for almost six hours. It was difficult for me, with the victims’ families so upset as I walked around on the blood of their loved ones. Some became very rude and challenged me angrily. The next morning I went back to cover follow-up stories, and the situation was almost the same.

This is the story of just one terrorist attack in Peshawar, the frontline city in the war against terror. We report on two or three bomb blasts every single day. The terror attacks have been going on for as long as 12 years, when America invaded Afghanistan and kicked the Taliban government out. In the terrorised FATA [Federally Administered Tribal Areas] region and Khyber Pakhtoonkha, media reporting is no game, even for the male reporters. Often when we rush to the blast scene, a second blast takes dozens or even hundreds of lives and many journalists are martyred.

For a female TV journalist, it is like being in a battlefield with enemies coming from all sides. In our society, and in the field of journalism, women may seem to be respected outwardly, but when we sit and discuss a report with a male colleague, they try to discourage us and cause problems. It is because of this that women are hesitant about coming into this field and why some women leave. But nowadays the main problem is that we are worried about our safety – our lives.

However it is encouraging that in a male-dominated society like Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where there is a cultural barrier that prevents women from working, 30 per cent of journalists are women. Of those, 10 per cent work for TV channels, 7 per cent in newspapers and 13 per cent in local and international radio.

The fierce competition between media organisations puts journalists at even higher risk. In the case of a blast or any emergency, I have to break the news. This pressure usually makes me tense, but being a professional I have to prove that our channel is the best at breaking news.

But that’s hard. If I break the news of a blast, the channel I work for will demand that I find more casualties and a higher death toll, to compete with other organisations. The producer and director back at head office don’t understand how critical the situation is on the spot. They do not understand the problems of a reporter.

I always try to tell the real story, but obviously I am a human being and often my emotions as a mother, sister and wife overcome me. In Pakistan, our organisations prefer women journalists to cover these types of stories because we can bring a human touch. When I report on blast victims’ families, I try to make it real and show the problems they must face after the sudden death of a loved family member.

Training and education are very important for reporters. Media organisations need to arrange more and more training.

Another reality for women journalists in my province is that people here do not accept that we need to work in offices and go outdoors. In their opinion, women are not supposed to go outside and they are still not willing to accept our work identity.

During my 17 years’ experience as a journalist, I have had many male colleagues who have been narrow-minded [about working with women]. They will always criticise – “Oh, you did well but you did not mention this issue in your beeper” or “Oh, your story is not balanced”.

But I always dig out many breaking news stories and act professionally, for example, when visiting Peshawar Central Jail to do stories about Dr Shakil Afridi [the Pakistani physician who helped the CIA locate Osama bin Laden]. Because I am a woman, often they don’t take me seriously and offer me a cup of tea – but I am confident about being a professional woman and doing this.

It also pains me that nowadays our organisations try to cash in on female journalists, using them to cover issues where the officials and authorities like having women journalists interview them.

In the current situation, the security risks and social pressures are the main problems for me as a female journalist. There is no doubt that males as well as females face many of these challenges in the field of journalism, but they do not hold them back. Each day I am not even sure that I will get home safely, but as a professional, no hurdle is too great.

—

Nadia Sabohi is an investigative reporter for Geo TV news in Pakistan, and their correspondent in Peshawar and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

Written By

Comments

Resources

- IFJ South Asia Media Bulletin, February 2023 02/15/2023 Download

- IFJ South Asia Media Bulletin, January 2023 01/18/2023 Download

- Nepal Press Freedom report 2022 01/03/2023 Download