Activities

Chhattisgarh: War in India’s Heartland

03 May, 2016 The central Indian state of Chhattisgarh, carved out of the state of Madhya Pradesh in 2000, has witnessed left-wing guerrilla warfare for more than three decades now. To counter it, the administration has turned the mineral- and forest-rich state into one of the most militarized zones in the country. Over the past five years, the banned Communist Party of India (Maoist) has been contained in Bastar, the southern part of the state, which is a resource-rich zone. The government, in collaboration with corporate entities is trying to control the natural resources of the state which has one of the largest adivasi (indigenous people) populations in the country. The Maoists as well as the adivasis have expressed their opposition to indiscriminate mining and forest felling.

The central Indian state of Chhattisgarh, carved out of the state of Madhya Pradesh in 2000, has witnessed left-wing guerrilla warfare for more than three decades now. To counter it, the administration has turned the mineral- and forest-rich state into one of the most militarized zones in the country. Over the past five years, the banned Communist Party of India (Maoist) has been contained in Bastar, the southern part of the state, which is a resource-rich zone. The government, in collaboration with corporate entities is trying to control the natural resources of the state which has one of the largest adivasi (indigenous people) populations in the country. The Maoists as well as the adivasis have expressed their opposition to indiscriminate mining and forest felling.

While anti-Maoist operations have been ongoing for several decades, and have intensified over the past year, in December 2015, senior police officials announced that they were set to “wipe out Maoists from Bastar at any cost” in what they called ‘Mission 2016’. In order to conceal state excesses in their attempt to uproot the Maoists, the police has censored and intimidated human rights defenders and the media. The suppression of democratic political dissent and the media has been legally sanctioned by The Chhattisgarh Special Public Security (CSPS) Act, 2005, which, in the garb of security clamps down on a vaguely-defined range of offences by allowing for arbitrary arrests and prosecution.

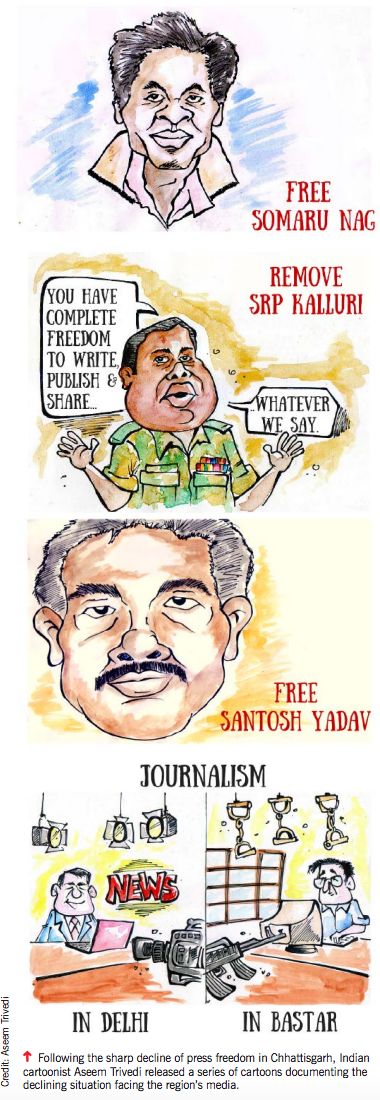

In the past one year alone, four journalists have been arrested under the CSPS and other laws, at least one was forced to leave Bastar and many others have been threatened.

The media in Chhattisgarh is extremely polarized and almost no independent reporting emerges from the region. Gathering news from the Maoist-dominated areas is challenging as they are far-flung and lack connectivity. Additionally, there is immense pressure from the police and administration on journalists who publish critical reports. Previously, journalists have been killed by the Maoists as well. On December 6, 2013, Sai Reddy, journalist for Hindi daily Deshbandhu, was beaten and stabbed by Maoists who believed he was a police informant. Ironically, in 2008, he had been charged under the CSPS Act and imprisoned for allegedly being close to the Maoists.

Most journalists are fearful of covert surveillance by the state. A few have found their private conversations being repeated in other contexts, confirming their suspicions that their phone lines are compromised.

The media is one of the most credible witnesses in a conflict-zone and, the most effective strategy of hiding state excesses is to eliminate the key evidence that can lead to national and international condemnation. In addition to using the law and direct state pressure, some vigilante groups close to the police and state administration, have taken it upon themselves to “discipline the media and other human rights defenders” in the region, by pamphleteering and sloganeering against specific individuals. Senior journalists, who have received physical threats, have confirmed that the newly emergent vigilante groups seem to be closely connected to the police. Indeed, the Samajik Ekta Manch, which has vowed to “fight Maoism till the end” bears an eerie resemblance to the state-sponsored counter-insurgency group Salwa Judum (Purification March), that had emerged in Bastar in 2005. On July 5, 2011, the Supreme Court of India declared this armed militia to be illegal and unconstitutional and had ordered that it be disbanded.

Arrests and intimidation

Somaru Nag, a stringer for the Hindi daily Patrika, was arrested on July 16, 2015 in Darbha town of Bastar district. His family was informed only three days later. He was accused of allegedly setting fire to equipment being used to build roads in Chote Kadma village and therefore furthering the Maoist agenda of blowing up roads to ensure that paramilitary forces do not enter the far-flung areas. Charges were brought under the Arms Act and sections of the law dealing with arson, banditry and criminal conspiracy. As a journalist from one of the region’s many indigenous communities, Nag is a relative rarity in Chhattisgarh. He has worked freelance for over three years with a special focus on human rights and rural welfare. It is believed that some of his reporting on the human rights consequences of security operations in Bastar could have earned him the enmity of the local police. Nag’s lawyers say the evidence against him doesn’t hold water.

Two months later, on September 29, 2015, Santosh Yadav a stringer for Dainik Navbharat, Patrika, and Dainik Chhattisgarh was arrested and charged for rioting, criminal conspiracy, and attempted murder. He was charged under the CSPS Act for “supporting banned terrorist groups” which in this case are the Maoists. Yadav had reported consistently on extra judicial killings and rapes said to have been committed by the security forces. He had a reputation for his reporting on human rights issues and in 2014 had one brush with the local authorities, when he was summoned to a police station, stripped and held for several hours. His most recent arrest on charges of participating in organized violence, followed soon after he accompanied a group of Bastar villagers to a police station to petition for the release of individuals held without any seeming basis. Both Yadav and Nag were considered to be journalists who wrote stories that made the administration uncomfortable.

These two arrests in quick succession rang warning bells amongst journalists. A delegation of journalists appealed to Raman Singh, the chief minister of Chhattisgarh in December, calling for the release of Nag and Yadav. In January, an international coalition of press freedom organizations and human rights groups, including the IFJ, addressed a letter to the chief minister, calling for charges to be dropped. Matters have if anything, have deteriorated.

Hounded out

There is a significant difference in the way the local and national media report on Maoist violence, resource extraction and state excesses. Most regional media in Chhattisgarh is unquestioning and open in its support to the government.

It is no surprise then that the authorities in Chhattisgarh feel that a large section of the national media is pro-Maoist, simply because it calls out the authorities on human rights violations or state excesses. The national media raises uncomfortable questions that the authorities would rather not answer.

The situation is made more complex by vigilante groups like the Samajik Ekta Manch, which can even turn violent. “We believe the only media is the media that co-operates with the police for the betterment of the region,” said Subba Rao of the Samajik Ekta Manch. The ‘enemy’ for these vigilante groups then becomes those who dare to expose the reality of Chhattisgarh today.

On December 19, 2015, Jagdalpur-based journalist Malini Subramanium reported on fake ‘surrenders’ of alleged Maoists for the news website Scroll.in. She had written regularly through 2015 about the difficulties of being a journalist in Chhattisgarh and about large scale human rights violations by paramilitary forces in the region. She relentlessly reported on sexual violence on adivasi women by security forces. Members of the Samajik Ekta Manch, visited Subramanium’s house close to mid-night on January 10, 2016 and intimidated her.

Subramanium returned from a reporting trip to Mardum, a village 40 km from Jagdalpur where the paramilitary forces had allegedly committed an extra-judicial killing in early February.

On February 8, members of the Samajik Ekta Manch gathered outside Subramanium’s house, shouting slogans like ‘Naxali Samarthak Bastar Chodo. Malini Subramaniam Mordabad’ (Naxal [Maoist] supporter, leave Bastar. Death to Malini Subramaniam). The demonstrators even urged neighbours to throw stones at her home, alleging that she supplied arms to the Maoists. The same night stones were thrown at her car, shattering its windscreen. It took two days for Subramanium’s FIR to be registered, and when the FIR was filed it was against “unknown people”, even though she had recognized some of the men who had sloganeered outside her house, including local political leaders. After the police intimidated Subramanium’s domestic help and her landlord, and overnight, she was forced to leave her home of six years on February 18, 2016.

A similar stratagem was used against an all-women legal aid collective that had been helping journalists and other human rights defenders in Bastar. The Jagdalpur Legal Aid Group (Jaglag) which had taken up the cases of Nag and Yadav, among others, was forced to close its establishment and leave, again overnight, in February.

A journalist for the BBC, Alok Putul, drew the police’s ire for having reported on Subramanium’s exit from the area. The following week, when he was in the villages in Bastar district, he got a call from a friend asking him to leave the area immediately as the police were looking for him. He did.

He was trying to report on extra-judicial killings and wanted a response from the police. The Inspector General (I.G.) Shiv Ram Prasad Kalluri texted Putul saying, “Your reporting is highly prejudiced and biased. There is no point in wasting my time in journalists like you. I have a nationalist and patriotic section of media and press which staunchly supports me. I would rather spend time with them. Thanks.”

At a press conference in Raipur on February 20, the I.G. was quoted as saying: “We don’t care about the national media. You have a different way of looking at things. We work with the media in Bastar, that sits with us, eats with us, and comes in helicopters with us.”

Putul informed the BBC in Delhi who in turn called Kalluri to interview him. The BBC story released an audio recording of the interview where Kalluri shouts at the journalist on the other side of the phone and questions his credentials as a journalist.

After repeated threats and intimidating visits by unknown people to his office in Bilaspur, Putul has decided to move base to Raipur, the state capital.

Who is a journalist?

On March 21, Prabhat Singh, a journalist from Dantewada for the Hindi daily Patrika, was arrested by the police for allegedly posting obscene content on WhatsApp and other sundry cheating cases. When produced in court, he told his family that he was repeatedly beaten while in prison and was not given any food. Interestingly, the complaint against Prabhat was registered by another journalist from Dantewada. The “obscene language” used by Prabhat is not unusual talk between reporters. Strangely, others who had used such language in the same forum were not arrested. Singh had reported on state excesses for a few years now. Charges have been framed against him and he remains in the Jagdalpur jail.

On March 21, Prabhat Singh, a journalist from Dantewada for the Hindi daily Patrika, was arrested by the police for allegedly posting obscene content on WhatsApp and other sundry cheating cases. When produced in court, he told his family that he was repeatedly beaten while in prison and was not given any food. Interestingly, the complaint against Prabhat was registered by another journalist from Dantewada. The “obscene language” used by Prabhat is not unusual talk between reporters. Strangely, others who had used such language in the same forum were not arrested. Singh had reported on state excesses for a few years now. Charges have been framed against him and he remains in the Jagdalpur jail.

Prabhat Singh’s arrest moreover, flies in the face of a ruling by India’s Supreme Court in March 2015, holding a vaguely worded clause of the Information Technology Act which allowed for arbitrary legal action as a violation of fundamental rights. The quashing of Section 66A of the Act – which allowed for three years imprisonment for posting “offensive, false or threatening information” was widely applauded as a significant blow in defence of free speech. But Prabhat Singh’s arrest seems to suggest that police and security agencies will continue to use the over-broad mandate of the impugned section to persecute journalists and private citizens, in the hiatus between executive action and judicial review.

Even as local journalists and civil rights groups got engaged in seeking his freedom, the Dantewada police arrested Deepak Jaiswal on March 26 on an eight-month old complaint of trespassing into the premises of a school and roughing up its staff. Both Prabhat Singh and Jaiswal have been regular contributors to local newspapers and were involved in a journalistic investigation into allegations that school staff in the district were conniving in large-scale cheating in examinations. In the absence of well instituted accreditation procedures, they have been mostly functioning without media credentials. Local authorities denied that Jaiswal was a journalist as he didn’t have a press card authorized by the government. However, Jaiswal has published close to ten front page stories on fake arrests by alleged Maoists in the past year.

Journalists in Bastar are forced to self-censor. Not doing so, can mean physical danger. “There are very few journalists left in Bastar who report objectively. And, obviously they fear for their safety,” said Bappi Rai, President, South Bastar Reporters Association. “As an association, we have decided to boycott any stories related to the police or the Maoists. If we can’t report objectively, we would rather not report. We will request our colleagues in the seven districts of Bastar region to join in this boycott,” he added.

Dwindling support, increasing fear

On October 10, 2015, about three hundred journalists from all over the state protested in the state capital, Raipur. They called for the release of journalists Yadav and Nag. But, the state government did not react. Instead, senior police officials of Bastar addressed the media and said they are serious about Mission 2016 – a year in which they claimed Bastar would be rid of Maoists and their sympathizers.

On December 18, 2015, more than three dozen journalists from across the state gathered on the main road of Jagdalpur, Bastar, to demand the release of Yadav and Nag. They were also demanding drafting of a law to ensure protection and independence of journalists to work in Bastar region of Chhattisgarh. Kamal Shukla, a freelance journalist, who organized both the protests noted the sharp reduction in the number of attendees in the second protest. “But, we consoled ourselves thinking Jagdalpur is not as accessible as Raipur,” he said.

However, even as the Chief Minister was assuring the leaders of this movement on the phone that their demands would be considered, journalists who had come from hundreds of miles away were told they would not be allowed to stay in hotels in Jagdalpur. Hotel owners requested the journalists to vacate the rooms immediately as they had informal orders from the police to not allow media personnel as guests. The situation remains the same even today; if a journalist checks-in to a hotel in Jagdalpur, the police come in to run a background check.

On March 5, journalists led by Kamal Shukla, demonstrated once again in the state capital, this time registering their protest against the ousting of Subramanium and Putul as well. Merely 15 journalists attend the demonstration and there was no representation from the Bastar region. An almost 70 percent drop in attendance from the previous demonstration in Jagdalpur was a stark reminder that the administration had stepped up efforts to silence independent voices emerging from Bastar.

Out on a limb

In small towns of India, the definition of a journalist is fluid. Neither regional and local news outlets nor the national ones have full-time correspondents in smaller towns. The norm is for a journalist to report for more than one news media. And since news gathering alone does not pay enough, about 90 percent of the journalists are forced to earn their livelihoods from other professions ranging from being contractors to owning small shops or driving taxis.

In such a situation, it is easy for the authorities to not recognise a journalist as one and it is even more easy to persecute him/her. “Prabhat [Singh] is not a journalist as per our records. How come a journalist can be involved in the task of making Unique Identification cards?” asked the Superintendent of Police, Dantewada immediately after the arrest. Prabhat Singh also had an office where he facilitated applications for ID cards.

This also makes it easier for the news organisations to abdicate responsibility towards their news gatherers on the ground. For instance, Patrika has not taken responsibility for Santosh Yadav, Prabhat Singh or Somaru Nag or come forward to help in their legal defence.

There are some journalists who are on the pay rolls of national dailies and television channels, but these are few and far between. Even those journalists cannot report independently as they have commercial and corporate pressures, given the interests of mining and industrial corporations in Chhattisgarh.

Most of the coverage of the villages in Chhattisgarh happens from large cities like Raipur and Bilaspur. “Journalists rarely go out in to the field,” says a Kanker based editor, Sushil Sharma. “If reportage has to be done over phone, calling from Raipur is the same as calling from Delhi,” he adds. The result is that news trickles out of the villages in very small bursts. There is almost no way to break into this information black hole that the authorities are successfully creating.

Sounding the alarm

In March, a fact-finding team of the Editors’ Guild of India, after a tour of Chhattisgarh state and consultations with media practitioners and officials, sounded the alarm about the dire threats to journalism. The team recorded that it had been unable, to “find a single journalist who could claim with confidence that he/she was working without fear or pressure”. The team summed up its findings in the following words: “The media in Chhattisgarh is working under tremendous pressure… There is pressure from the state administration, especially the police, on journalists to write what they want or not to publish reports that the administration sees as hostile. There is pressure from Maoists as well on the journalists working in the area. There is a general perception that every single journalist is under the government scanner and all their activities are under surveillance. They hesitate to discuss anything over the phone because, as they say, ‘the police is listening to every word we speak’.”

The “with us or against us” syndrome which calls for a suspension of journalistic autonomy and a submission to the diktat of the authorities, has spread wide and deep. In observations before the Editors’ Guild, Lalit Surjan, editor of Deshbandhu who works out of Chhattisgarh’s capital of Raipur, described the dilemmas of journalism in this fashion: “If you want to analyse anything independently, you cannot do it, because they can question your intentions and ask bluntly, ‘Are you with the government or for the Maoists’”.

Such polarization of viewpoints and the disseminators of information is but to be expected in a low-intensity conflict zone. However, it is that much more of a challenge to sustain objective and credible journalism.

Journalists arrested/killed in Chhattisgarh since 2011

| No | Date | Name | Organisation | Details |

| 1 | September 2011 | Lingaram Kodapi | Freelance Journalist | Arrested on charges of acting as a Maoist conduit |

| 2 | February 2013 | Nemichand Jain | Reporter for Hari Bhoomi, Nayi Duniya, and Dainik Bhaskar. | Stabbed to death by Maoists for allegedly being a police informer. |

| 3 | December 2013 | Sai Reddy | Reporter for Deshbandhu | Killed by Maoists for allegedly being a police informer. |

| 4 | July 2015 | Somaru Nag | Freelance reporter | Charged with burning down equipment to be used for constructing roads |

| 5 | September 2015 | Santosh Yadav | Reporter for Patrika | Arrested for being a Maoist sympathizer |

| 6 | February 2016 | Malini Subramanium | Reporter for Scroll.in | Intimidated by vigilante groups; forced to leave Bastar for her reports on sexual violence and extrajudicial violence by the security forces |

| 7 | February 2016 | Alok Putul | Reporter for the BBC | Intimidated by vigilante groups; forced to leave Bastar |

| 8 | March 2016 | Prabhat Singh | Reporter for Patrika | Arrested on charges of ‘obscenity’ and in a case of cheating |

| 9 | March 2016 | Deepak Jaiswal | Reporter for Dainik Dainadini | Arrested in a case of cheating |

(This is a part of the capsule report for the South Asia Press Freedom Report 2016 which is available to download in resource section.)

Supported by ![]()

Comments

Resources

- IFJ South Asia Media Bulletin, February 2023 02/15/2023 Download

- IFJ South Asia Media Bulletin, January 2023 01/18/2023 Download

- Nepal Press Freedom report 2022 01/03/2023 Download