Resources

Northern and Eastern Provinces, Sri Lanka: Legacy of Conflict

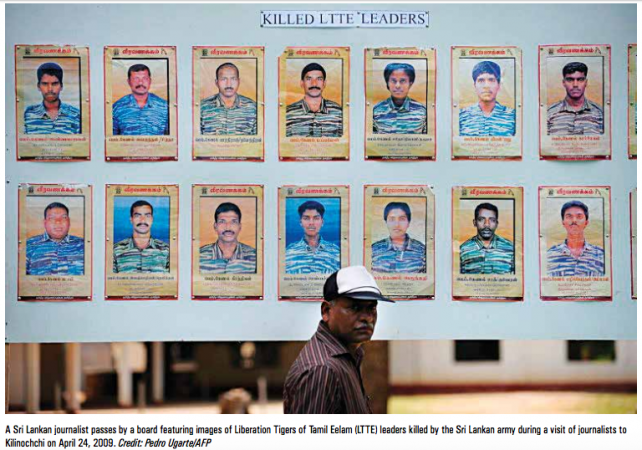

03 May, 2015 The Northern Province, one of the nine provinces of Sri Lanka, was temporarily merged with the Eastern Province between 1988 and 2006. The North Eastern province was a theatre of war between the Government of Sri Lanka and the rebel Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), which controlled large swathes of this territory. The province was recaptured by the army in 2009. Jaffna, the administrative headquarters of the province located on the eponymous peninsula, is a city still limping back to normalcy, attempting to recover from the ravages of three decades of war.

The Northern Province, one of the nine provinces of Sri Lanka, was temporarily merged with the Eastern Province between 1988 and 2006. The North Eastern province was a theatre of war between the Government of Sri Lanka and the rebel Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), which controlled large swathes of this territory. The province was recaptured by the army in 2009. Jaffna, the administrative headquarters of the province located on the eponymous peninsula, is a city still limping back to normalcy, attempting to recover from the ravages of three decades of war.

Valuable heritage

Jaffna has a rich tradition of critical newspaper journalism dating back to the nineteenth century. Morning Star, the first Tamil newspaper in the world was published in Jaffna way back in 1841 with Henry Martin as its editor. Other newspapers published in Jaffna in those days, were the Patriot, Jaffna Freeman and Literary Mirror. The Catholic Guardian and Hindu Organ were launched in 1876. Jaffna publications were also widely read by Tamil speakers outside Sri Lanka. Eelakesari a Tamil weekly published in Jaffna between 1931-1956 period had subscribers in India, Malaysia, South Africa, Fiji and Mauritius. Eelanadu, the first provincial daily was launched in Jaffna in 1956.

The Saturday Review, an English language weekly launched in 1982 was shut down by the government on July 1, 1983, around the time of the anti-Tamil pogrom in Sri Lanka. The recently passed Emergency (Miscellaneous Provisions and Powers) Regulations 1983 were used to seal the paper’s offices and the editor S. Sivanayagam had to flee to Tamil Nadu, India, soon after. The ban on the Saturday Review and another paper, the Suthanthiran, were lifted in January 1984 but the papers were subject to strict censorship by the government. Despite attempts to revive it around 1988, the paper was permanently shut down.

Uthayan (which means dawn) was launched in Jaffna in 1985 and is the only paper in the Northern Province that did not cease publication during the civil war. Over the years, its courageous journalism has been celebrated not only in Sri Lanka but overseas, with the newspaper winning coveted awards of excellence. Uthayan received the Sepala Gunasena Award for Defending Press Freedom in Sri Lanka in 2009, the year in which the island’s protracted war came to an end and journalism in Jaffna faced its toughest time.

Currently, four newspapers are published from Jaffna: One is a provincial newspaper and the other three being provincial (Jaffna) editions of the national papers. These four papers function with a staff of about 55-65 media workers and 40-60 area reporters. 20-25 journalists from Jaffna contribute to internet based media. Two television channels and one radio station operate from Jaffna. There are no journalists’ trade unions in Jaffna mainly due to the fact that media organisations are privately owned and trade unions are discouraged, in some cases, even restricted. Jaffna Press Club is the leading journalists’ association Jaffna while another association, North Sri Lanka Journalists Association which was once active, is now defunct. With the nationalist discourse being dominant, at present there is no discourse on rights of journalists among Jaffna journalists.

Caught in the crossfire

The media in Jaffna was a regular victim of hostilities during the armed conflict that lasted for 30 years. For instance, the Uthayan office faced aerial bomb attacks due to which the printing of the paper had to be temporarily halted. Media personnel were harassed by both the government forces and the LTTE and journalists were killed, threatened and abducted. Since the armed conflict in Sri Lanka ended in 2009, Jaffna media has been free of the risk of being caught in cross fire or bomb blasts.

However attacks against the media in Jaffna continue and journalists are being subjected to intimidation and harassment. During the last year there were several instances when the police interrogated and attempted to control Jaffna media: On July 28, 2014, Omanthai Police called several journalists who protested against military intimidation for questioning; senior journalist and media activist Thayaraparan Ratnam was interrogated by Criminal Investigation Division on October 3; and, recently, a freelance Tamil journalist from Jaffna was called in for an investigation regarding his coverage of the assault of a school girl by Sri Lankan police officers and later detained. On April 7, 2015, three Tamil journalists were harassed and threatened by police officers in Jaffna, as they were leaving a protest. The police officers who appeared to be intoxicated chased the journalists while brandishing knives.

The military was also a source of harassment of the Jaffna media during the last year. Military officers reportedly visited printing presses in Jaffna, harassed newspaper agents and instructed printer owners to alert the military before printing the papers.

Journalists in Jaffna also faced threats and attacks from unidentified groups. In September 2014, Sinnarasa Siventhiran, an area correspondent for Uthayan, escaped a murder attempt. Though the perpetrators introduced themselves as officers from the Criminal Investigation Division, they are still unidentified. On December 6, 2014, senior journalist and Jaffna Press Club Advisor, R. Dayabaran, was threatened over the telephone when he was travelling to Colombo to participate in a media protest against the suppression of media during the Rajapakse regime.

Censorship is another major obstacle to realising freedom of expression in Jaffna. There were instances when media was not allowed to cover certain incidents. In July 2014, journalists who went to report the pre-emptive surveying of private land by Sri Lankan Navy were threatened and journalists covering a case of rape, allegedly committed by Navy personnel, were forcibly removed from Jaffna Courthouse by persons in civilian clothing and were warned not to publish any news on the proceedings. Screening of a film was disrupted in Jaffna and in November 2014, intelligence personnel threatened Jaffna Press Club demanding that the Club should not provide space for an event being conducted by the political party Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP). Along with the censorship by the government and armed forces a culture of impunity has lead to self-censorship in the media.

Legal restrictions

While most restrictions on freedom of expression are extralegal, there are legal restrictions as well. Many laws in Sri Lanka ranging from constitutional provisions to penal laws restrict expression. Though Sri Lanka’s armed conflict has ended, the Prevention of Terrorism Act which violates human rights norms is still in force. The Act makes serious incursions in to freedom of expression and the media by requiring in certain circumstances governmental approval for printing, publishing and distributing publications and newspapers15.

Lack of safety

Among the other issues currently faced by journalists in Jaffna is job insecurity. Many media workers, especially provincial journalists work without a valid contract of employment. Lack of insurance cover and lack of safety training remain areas of concern. Though safety trainings were provided a few years ago by organisations such as INSI, Inter News and IFJ, there have been no follow ups due to lack of funding and restrictions on international organisations have been a barrier to conducting trainings in recent times.

Further, an environment hostile to media trainings seems to be emerging in the country. In July 2014, 11 journalists from Jaffna who were travelling to a media workshop in Colombo were stopped and interrogated by Government armed forces. Another workshop was cancelled in November 2014 due to threats and intimidation by armed forces. To address the need of safety training, first, an environment where journalists can freely attend media trainings needs to be created. Likewise, there is also a need to build professionalism. Another challenge in the way of pressing for safe journalism is the lack of unity among journalists. In Sri Lanka, journalists are divided on the lines of political ideologies and ethnicities, and there is a disconnect between journalists from the South and those from North.

The social context which continues to be sharply polarised on ethnic and political lines, has an impact on the practice of ethical journalism. It is noteworthy that several media organisations in Jaffna have strong political affiliations; for example, both Uthayan and Thinamurusu dailies are owned by members of parliament.

While Jaffna journalists face many challenges, the culture of impunity is the worst enemy of freedom of expression in Sri Lanka. Uthayan has faced over thirty attacks during and after the war and to date no perpetrator has been brought to justice. No person has so far been convicted in the judicial proceedings on the assassination of journalist Mylvaganam Nimalrajan in Jaffna 15 years ago. No person has been convicted of the attempt to murder Sinnarasa Siventhiran, the progress of the investigation is unknown and those who threatened Dayabaran still roam free. There is no progress in the investigation in to the disappearance of journalist Subramaniam Ramachandran who went missing eight years ago after he was arrested by the Sri Lankan military.

Today, when Sri Lanka is moving towards constitutional and political reform, it is important to end the culture of impunity and take action against individuals and groups responsible for violations of media freedom. As part of the reform process, it is essential that full and open investigations are held into all these cases.

EASTERN PROVINCE, SRI LANKA: Significant Shift

The Eastern Province is one of the nine provinces of Sri Lanka, with its capital at Trincomalee. The province got legal status in 1987 following the 13th Amendment to the Constitution which established provincial councils. However, from 1988 until 2006, it was merged with the Northern Province to form the North Eastern Province. Large swathes of this province were under the control of the LTTE during the civil war, and the entire territory was captured by the Sri Lankan army in 2007.

During the prolonged ethnic conflict and war, the media in the Eastern Province was caught between the LTTE and the government authorities. Armed groups owing allegiance to the Sri Lankan army added to the volatile situation in which the media had to operate. Even though no major incidents threatening media freedom were reported from the province from May 2014-2015, the consensus is that there was a perceptible shift in the working environment for media personnel since the regime change in January 2015. Journalists recall that incidents of being followed by security forces and restrictions imposed by them in accessing information created an atmosphere of intimidation which has reduced to a great extent.

While most national-level publications enjoy circulation in the region, only one, Vaarauraikkal, in Tamil, is published specifically for that province. There are an estimated 200 media workers in the East, the majority concentrated in the Ampara District.

When contrasted with the period before the end of the war, when journalists were assailed by both the State and the LTTE, the situation is considered to have improved still further. However, while certain incidents of telephone threats by displeased regional politicians were reported, media associations acted in concert in those cases to express condemnation. The police is also said to have been responsive in recording the complaints of those affected, as well as advising the perpetrators against repetition. In these incidents, the victims did not seek to pursue action in court.

A significant demographic characteristic of the Province is its diverse population, even as the Tamil and Muslim communities make up the political majority, a fact reflected in the issues faced by media workers there. It is reported that in some instances, law enforcement officials were indifferent and showed a lack of interest in pursuing complaints made by media personnel, particularly if the complainants were Tamil or Muslim.

In 2014, before the regime change, some workshops organised for journalists were either threatened with disruption or were disrupted by the security forces. In this regard, a workshop organised by an NGO for Tamil journalists on the topic of effective implementation of the recommendations of the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) was disrupted by the security forces, who reportedly surrounded the workshop venue. Interestingly, the Sinhala phase of the workshop that preceded the Tamil event had concluded without difficulty, despite participants receiving information of it possibly being blocked by authorities.

Restricted access

The centralisation of access to government information resulted in a general administrative reluctance to part with information, as well as a significant amount of red tape, which in turn contributed to the indirect censoring of the media. For instance, provincial institutes, particularly during the previous regime, refused to divulge information of state affairs, persistently referring journalists to media spokespersons operating from the central government. However, their lack of awareness of and access to the relevant information outlets at the central government imposed unnecessary obstacles on journalists. That these outlets and spokespersons are based in Colombo also had its adverse impact on the news-gathering ability of East-based journalists.

Another significant issue reported to impact media freedom in the East is the covert affiliations of some journalists with politicians. These affiliations are said to affect the impartiality of the media in the East and, by extension, its credibility. This is further exacerbated by the reliance of journalists on political patronage to advance their careers, particularly within, though not limited to, the state media. The lack of a standardisation of recruitment criteria, coupled with the culture of political patronage, has contributed to the declining quality of journalistic output in the region. Furthermore, the media in the region is also adversely affected by the culture of divisiveness within the industry, which is contributed to by both political partisanship as well as commercial competitiveness.

In terms of women in journalism, all estimates indicate drastically low participation, the most generous one counting less than ten women in the Eastern Province engaged in journalism. The general atmosphere is one adverse to women working in the media, both in terms of cultural factors and security factors, although the two tend, sometimes, to feed off each other. The need for male escorts particularly at night, especially where there is limited access or transport to certain areas imposes further restrictions on the mobility of women journalists.

Media workers in the Eastern Province are organised, and several bodies are active. Some, such as the Coastal Area Media Organisation, are divided along ethnic lines, comprising Tamils and Muslims only, while other organisations are multi-ethnic. In all, there are six organisations reported to be in operation in the province: Coastal Area Media Organisation; Trincomalee Journalists’ Association; Kathankudy Media Forum; Ampara District Media Association; Trincomalee District Media Association and Batticaloa District Media Association. The Digamadulla Media Association is reportedly no longer in operation. With the new regime, there is hope that these organisations can work towards making the environment safe for the practice of ethical journalism.

Media Workers from the North-eastern Province Killed since 1989

| No | Date | Name | Organisation | Details |

| 1 | November 6, 1989 | I. Shanmugalingam | Staff Reporter, Eelanaadu & Eelamurasu | Kidnapped and executed in Jaffna by the LTTE |

| 2 | 1997 | Thiagarajah Selvanithy | Founder editor, Tholi | Abducted and later killed by the LTTE |

| 3 | October 19, 2000 | Mylvaganam Nimalarajan | Reporter, BBC | Reportedly shot by the Eelam People’s Democratic Party (EPDP), a pro-government paramilitary organisation |

| 4 | May 31, 2004 | Aiyathurai Nadesan | Reporter, Virakesari | Shot in Batticaloa, reportedly by the Tamil Makkal Viduthalai Pulikal (TMVP) or ‘Karuna Group’ |

| 5 | August 16, 2004 | Balanadarajah Iyer | Founder and editor, Thinamurasu newspaper | Shot by the LTTE in Colombo |

| 6 | April 28, 2005 | Dharmeratnam Sivaram ‘Taraki’ | Editor, Tamilnet | Kidnapped by four unidentified men in a white van in Colombo. His body was found the next day, beaten and shot in the head. |

| 7 | January 26, 2006 | Subramaniyam Sugirdharajan | Correspondent, Sudar Oli | Shot by unknown gunmen in Trincomalee |

| 8 | May 2, 2006 | Ranjith Kumar | Journalist, Uthayan | Shot in the Jaffna office of Uthayan reportedly by the EPDP |

| 9 | May 2, 2006 | Suresh Kumar | Journalist, Uthayan | Shot in the Jaffna office of Uthayan reportedly by the EPDP |

| 10 | April 16, 2007 | Chandrabose Suthaharan | Editor, Nilam magazine | Shot in Vavuniya District by unidentified gunmen |

| 11 | April 29, 2007 | Selvarajah Rajivarnam | Reporter, Uthayan | Shot in Jaffna by unidentified gunmen |

| 12 | August 1, 2007 | Sahathevan Nilakshan | Journalist, Chaalaram | Shot in Jaffna by unidentified gunmen |

| 13 | May 28, 2008 | P. Devakumaran | Journalist, Shakthi TV | Hacked to death reportedly by the EPDP |

(This is a part of the capsule report from the conflict zones for the South Asia Press Freedom Report 2015 which is available to download in resource section.)

Supported by ![]()

Written By

IFJ Asia-Pacific

IFJ Asia-Pacific

The IFJ represents more than 600,000 journalists in 140 countries.

For further information contact IFJ Asia-Pacific on +61 2 9333 0946

Find the IFJ on Twitter: @ifjasiapacific

Find the IFJ on Facebook: www.facebook.com/IFJAsiaPacific

Comments

Resources

- IFJ South Asia Media Bulletin, February 2023 02/15/2023 Download

- IFJ South Asia Media Bulletin, January 2023 01/18/2023 Download

- Nepal Press Freedom report 2022 01/03/2023 Download