The Road to Resilience: Impunity

THE QUEST FOR JUSTICE

Intimidation, violent attacks and killing of journalists are a grave violation journalists’ right to perform their duty as well as the public’s right to know. When these violations of freedom of expression and journalists’ rights occur with impunity, a climate of fear becomes the norm and lack of accountability permeates public discourse. In conflict zones in particular and also in conditions of deteriorating law and order, the media have an even more critical responsibility to inform the public. But it is precisely these conditions that breed impunity.

Recognizing the need to evolve multi-pronged approaches to tackle impunity at a global level, the UN Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists was endorsed in 2012 by governments, journalist associations, media houses, NGOs, INGOs and the UN system. It is no coincidence that South Asia is home to two of the four countries selected for the first phase: Nepal, Iraq, South Sudan and Pakistan.

The Plan of Action aims to create a free and safe environment for journalists and media workers with a view to strengthening peace, democracy and development worldwide. Its measures include the establishment of a coordinated inter-agency mechanism to handle issues related to the safety of journalists as well as assistance to countries to develop legislation and mechanisms favourable to freedom of expression and information and supporting their efforts to implement existing international rules and principles. The Plan recommends cooperation between governments, media houses, professional associations and NGOs and to conduct awareness raising campaigns on a wide range of issues such as existing international instruments and conventions; the growing dangers posed by emerging threats to media professionals; as well as various existing practical guides on the safety of journalists.

Indeed, one of the key characteristics of the UN Plan is the multi-stakeholder approach. This is based on the realization that the issue of journalists’ safety is much too complex to be able to be resolved by any single actor. By drawing on the varied strengths and resources of different stakeholders collectively, there is a better prospect for improving the safety of journalists and ending impunity.

Four years on, efforts to implement the UN Plan of Action have provided signi cant lessons learnt and the plan is increasingly seen as a framework to be applied in countries across the world, where media workers face hostile environments through a broad and concerted effort.

UNESCO states that the world over, only one in 12 cases of killed journalists has been resolved, and the situation in the South Asia is even worse. Indeed, because the region has an almost perfect record of impunity the murderers of journalists often walk free, and in most cases, even investigations prove elusive. For a long time, the South Asia region has been the worst in the world in terms of impunity for crimes against journalists. Despite all eight countries in the region – Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal, Maldives and Bhutan – being under democratic regimes for at least ve years, the persistence of impunity in these countries has remained a big challenge for governments and democracy.

Bangladesh police officials parade suspects in Dhaka on August 14, 2015, after their arrest in connection with the murder of secular blogger Niloy Chakrabarti. , known by the pen-name Niloy Neel. Bangladesh police said they arrested two suspected members of the banned Islamist group, Ansarullah Bangla Team, over the brutal killing of ‘atheist blogger’ , known by the pen-name Niloy Neel. Photo: MUNIR UZ ZAMAN / AFP

BANGLADESH: ARRESTS MADE

Bangladesh is among the five South Asian nations in the CPJ’s Impunity Index among the 14 countries with the worst records in punishing the killers of journalists. This lack of action, delay in investigation, and absence of convictions, may serve to embolden perpetrators, and is contributing to the culture of impunity for acts of violence. Since 1995, 47 journalists and seven bloggers have been murdered, yet there have been only a few convictions, and trials are yet to commence in many cases.

However, this year, there were some positive developments. On December 31, 2015, eight persons involved in the murder of blogger Rajib Haider were convicted and sentenced. Haidar, 35, a blogger and activist calling for the execution of Islamist leaders for crimes committed in the Liberation War of 1971, was hacked to death on February 15, 2013 near his house at Mirpur. The Dhaka Special Trial Tribunal sentenced to death Md Faisal Bin Nayem alias Dweep and absconding Redwanul Azad Rana. Rana was considered as the mastermind of the murder while Nayeem attacked Haider with a meat cleaver. Maksudul Hasan alias Anik was given a life term sentence, Md Ehsan Reza alias Rumman, Nayem Sikdar alias Iraj and Na s Imtiaz were given 10-year jail terms each, ve-year imprisonment were granted to chief of militant group ABT Mufti Jashimuddin Rahmani and SadmanYasir Mahmud was given three years in prison.

In some cases of murder, the Bangladesh Police made swift arrests and charged them. Although progress in investigation is mostly slow and incomplete, the arrests are a relief. On September 1, 2015, ve militants of the banned Ansarullah Bangla Team (ABT) were charged with the murder of Oyasiqur Rahman Babu in March 2015. The charge-sheet led at a Dhaka magistrates court listed Zikrullah alias Hasan, 19; Ariful Islam, 19; Saiful Islam alias Mansur, 23; Junayed alias Taher, 30; and Abdullah alias Akram Hossain, 26 in connection with the murder. Zikrullah and Ariful were caught by locals immediately following the murder and handed over to the police. However, Taher and Abdullah remain on the run and at large.

On August 29, Dhaka Police arrested Kausar Hossain Khan, 29, and Kamal Hossain Sardar, 29, for the murder of Niloy Neel, who was hacked to death in another ‘machete murder’ on August 7. The suspects are reported to be also members of the ABT. Two others, Saad-al-Nahin and Masud Rana, were arrested two weeks earlier for their suspected involvement in Niloy’s death. On August 18, Bangladeshi police arrested Bangladeshi-Britisher, 58-year-old Touhidur Rahman, and two other suspects Sadek Ali and Aminul Mollick, for the killing US- Bangladeshi blogger and author Avijit Roy. Most of them are currently awaiting trial in jail.

In November 2015, following the brutal killing of Zaman Mehsud, protests were held in in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa condemning the murder and calling on the government to arrest the culprits. Zaman Mehsud is one of 32 journalists and media workers killed in South Asia since May 2015. Photo: BANARAS KHAN / AFP

PAKISTAN: SIGNIFICANT VERDICT

March 16, 2016 marked a rare occasion for journalists in Pakistan to celebrate the third verdict convicting a murderer of journalist. A district court in Karak in northwestern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan convicted the killer of Ayub Khattak who was murdered in 2013.

The judge found the prosecution’s evidence “consistent and con dence inspiring and it could not be riddled with any sort of doubt concerning the main [accused] Amin Ullah and further said that “the prosecution has been successful to prove its case against him to bring to home charge and the court nds himguilty”.The judge ordered life imprisonment,of which 15 years will be rigorous, and also awarded a compensation amounting to PKR 500,000 (about USD 5,000) to the heirs of Ayub Khattak.

This court verdict comes after Pakistan suffered well over 100 fatalities of journalists since the country joined the US-led war on terror after the terrorist attacks on the United States in September 2001. Thus far, only two cases of journalists’ murders in Pakistan have been investigated and the accused prosecuted and convicted: the murders of American journalist Daniel Pearl and Geo News TV channel’s reporter Wali Khan Babar. All the three cases still await completion of legal process as the convicts’ appeals against convictions are pending in appeal courts.

The celebration did not last long. The Taliban – one of many predators of the free press in Pakistan – delivered yet another threat: “Everyone will get their turn in this war, especially the slave Pakistani media,” Ehsanullah Ehsan, spokesman for Jamaat-ur Ahrar, splinter group of the Taliban in Pakistan currently hiding in border areas of Afghanistan, tweeted. “We are just waiting for the appropriate time.”

The price of ghting impunity in Pakistan is very high. Some seven persons, including eyewitnesses, prosecutor, investigators and cops, were killed while tracking down the killers of Wali Khan Babar, his brother Murtaza Khan Babar told a UNESCO- organized national conference on Validation of Journalists Safety Indicators in October 2015. “You cannot imagine what price you will pay if you pursue the murder case of a journalist in Pakistan,” he told the Freedom Network, a media development organisation.

Before Pakistan was chosen as one of the pilot countries for the UN Plan of Action on the Journalists’ Safety and the Issue of Impunity in 2012, safety of journalists and media houses was at the lowest ebb with the country labelled as the “most dangerous” country for journalists in the world. No one was taking these attacks, killings, threats, harassments and intimidations of journalists seriously enough and perpetrators of horrific crimes were encouraged by deep-rooted impunity in the country. Disunity among media owners was adding fuel to the re. Then came the split in the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists with two contesting groups claiming victory in the elections held on October 26, 2013.

The failed assassination attempt on the country’s renowned TV journalist Hamid Mir led to the setting up of a judicial commission on April 21, 2014, two days after the attack, to probe who attacked him and why. The Hamid Mir Judicial Commission, mandated to complete the probe within three weeks, submitted its report to the government only on December 15, 2015. The report has still not been made public, but a leaked report indicates that the commission was unable to determine the actual reasons or identify the culprits responsible for the attack. The Commission in its report notes that “there was complete failure on the part of all the law enforcing agencies in the performance of their duty to properly investigate the instant case.” The Commission also noted that the first information report (police FIR) was led four days after the incident, thus delaying proper investigations. It is indeed indicative of entrenched impunity that even in such a high-profile case, there has been a dismal failure of the law enforcement authorities to take action.

With so little hope for justice, and with intimidation and threats causing not just physical harm but also psychological breakdown, self-censorship emerged as a major tool to stay safe. Freedom Network’s 2016 report on State of Media Freedom in Pakistan 2015, points to reasons that journalists and media houses are censoring themselves to stay safe as attacks, threats, harassments and intimidations continue unabated from all sides, including state and non-state actors.

Using the unique platform of the Pakistan Coalition on Journalists Safety, where all media stakeholders, including owners, working journalists and the government, are well represented for the first time, the issue of journalists and media houses’ safety and impunity have become a national agenda. Professional editors also joined the efforts aiming at addressing the security concerns of the journalist community and media industry by launching the ‘Editors for Safety’ (EfS) initiative to immediately report harassment and attacks once such cases are brought to its notice.

A significant aspect of this initiative is that despite serious differences among big media houses and their owners, they decided to work together towards the basic issue of safety and security. The results are encouraging as journalists in distress are getting help through the EfS.

Another big leap was taken to institutionalize journalists’ safety issue with Pakistan becoming a member of a small group of countries where safety hubs were established in partnership with press clubs to document and monitor each and every attack on journalists and media houses. In addition, efforts are made to link journalists in distress to the available governmental and non- governmental support systems and processes at local, regional and federal levels to mitigate the risks they may face.

Supplementing this initiative, Pakistan Journalists Safety Fund (PJSF) was reactivated in December 2015, to assist journalists in distress in four different categories – evacuation, legal, medical and compensation to deceased families of killed journalists. Since its launch in 2010 and until March 2016 around 40 journalists were assisted through the fund.

Of late, the government also woke up to the alarming situation of journalists’ safety and took up a private member’s Bill about journalists’ protection. The Senate Standing Committee on Information and Broadcasting invited all stakeholders to join deliberations on a draft journalists’ protection bill. Journalists’ representatives and safety specialists have come forward to use the goodwill gesture of the government to enhance the security of journalists and media houses.

Advocacy through the PCOMS platform seems to be paying back dividends to ght impunity. Media houses are moving away from a conservative look at the issue of journalists’ safety to more responsive behaviour, since staffers of TV channels are more vulnerable and exposed to risks than print media journalists. Actions taken could include relocating journalists and their families in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa receiving threats from the Taliban, safer locations within the country. Similarly, another TV channel’s management took a stand and defended its journalist in Karachi who had received threatening calls from a sitting minister of the Sindh government. The management thanked the PJSF for approving a fund to engage a lawyer to challenge the minister in a court of law but declined to take the fund saying that the channel’s management would pay the bill for the legal case against the minister from its own resources. These small but important gestures by media houses must be encouraged in order to pressurize managements that are not as responsive.

Pakistan is facing a decisive moment to bat for the issue of safety and security. While both national and international allies of the Pakistani media have been doing a lot to help bring about an enabling environment for journalists and media organisations to work independently and professionally, final pushes must accompany renewed support – both technical and resources – to keep journalism going in Pakistan.

NEPAL: LENGTHY TRANSITION

Impunity reigns high as the country is still under the political transition after the end of the armed Maoist con ict. The decade-long con ict ended in November 2006 after the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement betweenthe government and the Uni ed Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist). The agreement between political parties which was signed to bring a logical conclusion to the peace process, ironically increased impunity as some of the provisions agreed upon by the political parties weakened the rule of law, especially with regard to the con ict-era cases.

Since 2001, 35 journalists in Nepal have been murdered and four others disappeared. Yet, only five cases have been taken to the stage of prosecution while many are not even being investigated. Among six prosecuted cases, in the cases of Birendra Sah, Uma Singh, Dekendra Thapa and Yadav Paudel, the murderers have been convicted at least by one court and in the case of murder of media industrialist Jamin Shah, the case is still in the court.

A breakthrough achieved in 2016 is the arrest of mastermind of the murder of Arun Singhania. Singhania, owner and editor of Janakpur Today newspaper and Radio Today, was killed in broad daylight in March 2010. Police in April, 2016 claimed that their investigation pointed to suspended MP Sanjay Kumar Sah as the mastermind behind the murder. Sah was named in a news of a looting and Sah paid contract killers Chandra Deep Yadav and others to kill Singhania. The police arrested Yadav, a fugitive in other crimes as well, in March, 2016 leading to the conclusion of the case.

The Nepal International Media Partnership (NIMP), an alliance of 14 international organisations including the IFJ, SAMSN, UN agencies, global media associations, freedom of expression advocates and media development organisations, called on the Nepali government to take effective steps to resolve all serious cases of attacks and killings of journalists as well as introduce a journalist safety mechanism at the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC). A report published in March 2016 following a six-day mission to Nepal in April 2015, states that there is an ongoing need to address the issue of safety of journalists and other media workers in Nepal.

The two key objectives are: the provision of protection for journalists when the need arises and effective tools to combat impunity when attacks do occur or are threatened. The recommendations call for effective steps to resolve all serious cases of attacks on journalists; the implementation of the Working Journalists Act; the development of ethical guidelines and professional standards and protection measures for all media staff.

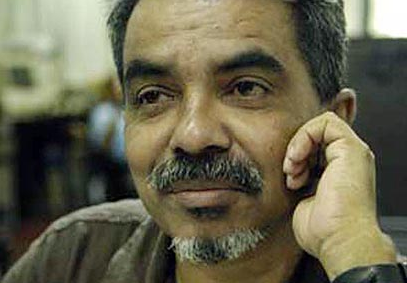

Sri Lankan journalist and cartoonist Prageeth Eknaligoda has been missing since January 2010. In the years since his wife, Sandhya, has led a massive campaign calling for justice. She talks to reporters outside a Colombo Court in March 2016 during the trial of those charged with his abduction. Photo: Sunanda Deshapriya

SRI LANKA: PLEDGES AND PROMISES

Ending impunity against the violations of freedom of expression in Sri Lanka has been an uphill task for media freedom organisations, locally and internationally. Leaders of the new government had pledged to ensure press freedom and investigate killings and adductions of journalists, and attacks against journalists and media once they come to power. On several occasions after coming to power the government promised to appoint a special unit to investigate them. No such commission has been appointed so far.

Out of dozens of killings and attacks only one case has been investigated and charges led in the courts: the case of the enforced disappearance of Prageeth Eknaligoda. There have been no official statements on any other incident being investigated, except occasional reporting of the investigation into the killing of the former editor of the Sunday Leader, Lasantha Wickrematunge.

On March 9, 2015 the President’s Of ce announced the appointment of a special committee to provide reparation for professional journalists who suffered injustices, faced disturbance and damage to their property during their work from January 2005 to January 2015. This period covered the two terms of former president Mahinda Rajapaksa. The Presidential Office informed the journalists who are survivors of injustice to submit all the data and information which can prove injustice and loss suffered, along with their professional identification to the Presidential Secretariat.

AFGHANISTAN: NO ACCOUNTABILITY

Impunity reigns high in Afghanistan where very few perpetrators have been held responsible in the targeted killings of journalists. Statistics by the Afghanistan Journalists Centre (AFJC) show that nine out of ten cases of murders of journalists have not been prosecuted. There had been prosecutions in the murder cases of state-run National TV reporter Sayed Hamid Noori (killed in November 5, 2010), and editor-in-chief of Andkhoi magazine Rahman Qul (murdered in February 17, 2007) and a primary court had issued verdicts against the murderers of Associated Press photographer Anja Niedringhaus (killed on April 4, 2014) and former ISAF reporter Palwasha Tukhi (murdered on September 17, 2014). However, assailants of other journalists continue to enjoy complete impunity.

Although the current national unity government has reiterated its commitment to press freedom and vowed to end impunity, journalists are still publicly threatened and targeted in acts of violence, and the country is yet to see the commitment turned into reality. President Ashraf Ghani, the first vice-president Abdul Rachid Dostom and the Chief Executive Officer Dr Abdullah Abdullah had vowed to put an end to impunity for crimes against journalists and media workers time and again.

INDIA: DISMAL RECORD

India is the largest democracy in the world and free from major armed confiict. Yet, its record on punishing the murderers of journalists is poor. With 31 murders of journalists since 2010 and 80 since 1990, most with none of the alleged perpetrators brought to justice, impunity is rife in India.

The Press Council of India (PCI) in its 2015 special report noted that among 80 cases of journalist murders since 1990, justice has been delivered in only one case – that of the gang rape of a female journalist in Mumbai in 2013 as it was tried under the newly amended anti-rape laws in a fast-track court. It said that in most instances, either the cases are pending in court or the police are yet to file charges. Journalist associations have been demanding a separate law for the protection of journalists and speedy prosecution in cases of murders.

The PCI report on safety of journalists states that ‘most of the journalists felt that whenever a journalist was killed, the state government concerned, including the Chief Minister and political leaders react and promise stringent action… after the din and noise died down, nothing happens.’ It further added: ‘in most cases, the police take years to file the charge sheets and arrest the culprits, who usually had support of the political and official establishment.’ There is a record of even the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) dismissing some cases for ‘lack of evidence’.

MALDIVES: POOR PROGRESS

Impunity has many faces – and one of them is journalist Ahmed Rilwan of Maldives. In April, 2016, more than 600 days after Rilwan had gone missing, the Maldives police said that he was abducted on August 8, 2014. It was the rst time that the police had admitted it was an abduction despite evidence having surfaced much earlier pointing to such a possibility. Members of the Kuda Henveiru gang had followed Rilwan for over two hours on the night in question and abducted him at knifepoint outside his apartment. The police said Rilwan’s abduction was planned well in advance.

The Minivan News journalist went missing after he was last seen boarding a ferry travelling to Hulhumale Island from the capital Male. Despite massive search efforts, journalist community’s demonstrations and campaigns, police were unable to provide any information about his whereabouts. Three suspects were arrested within a month of his disappearance but were released without charge.

In January, 2016 Maldivian President Abdulla Yameen broke his silence on Rilwan’s disappearance and requested the home minister to ‘do everything the government can’ to nd him. Although recent police statements raise hopes for justice, it could still be a long wait as many suspect the involvement of in uential political gures in the abduction. One of the suspects who followed Rilwan before the disappearance has since left the country.

Case Studies

PRAGEETH EKNALIGODA: VANISHING JUSTICE?

Investigation into the enforced disappearance of journalist and cartoonist Prageeth Eknaligoda was revived in 2015 and charges were led against a number of members of the security forces. The investigation and the court case of the enforced disappearance of Eknaligoda provide a classic scenario of zig zags and difficulties in ending impunity and ensuring accountability in a post-war transitional society.

Investigation into the enforced disappearance of journalist and cartoonist Prageeth Eknaligoda was revived in 2015 and charges were led against a number of members of the security forces. The investigation and the court case of the enforced disappearance of Eknaligoda provide a classic scenario of zig zags and difficulties in ending impunity and ensuring accountability in a post-war transitional society.

Eknaligoda was abducted on 24 January 2010, just two days before the presidential election after the war’s end. He openly supported the joint opposition candidate against the incumbent “war victory” president Mahinda Rajapaksa. For five years until the regime change took place there was no proper investigation into his disappearance. Instead, stories were fabricated by ruling party members and higher of cials that he was living in Europe.

In the meanwhile, a campaign led by his wife Sandya Eknaligoda and supported by local and international actors gathered momentum. By the second presidential election in January 2015, the issue of Eknaligoda’s disappearance had become of national and international concern.

The civil society groups that played a decisive role at the 2015 January election were able to highlight media suppression and violence unleashed against journalists and media under the Rajapaksa regime. Accountability for human rights violations in Sri Lanka was long overdue by that time and Eknaligoda’s enforced disappearance had become a much- highlighted issue.

Once the investigations began, obstacles started to appear one after the other. The clue to the investigation was a mobile phone number that had been used for the abduction of Eknaligoda. First it was the mobile phone operator, Dialogue, refusing to provide relevant phone conversations on technical grounds. Soon it was found that the Sri Lankan Army had a hand in the abduction. Two former cadre of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) who had become informers for the military were arrested, once information regarding phone calls was discovered. Following the information given by them, eight army personnel were arrested.

At this stage, the military refused to release relevant documents or allow access to military instalments. The Magistrate had to intervene several times to make military commanders cooperate. At the second stage of the investigation it was revealed that Eknaligoda was taken to an army camp in the East, and interrogated on some presidential campaign material he had produced. Even after the Magistrate’s repeated requests to the army commander to release the required information, up until March 14, 2016, police investigators did not receive it. When the case was taken up on March 14, 2016 the State Council Deleepa Pieris requested the Magistrate to order the army commander to release the necessary information.

It was reported that attempts were made to replace the state prosecutor who had been doing an exemplary job in pursuing the truth and pressuring military to provide necessary information. In fact he was removed from the case but the Attorney General had to retract his order due to media and civil society pressure.

As the suspected military intelligence personnel were arrested and remanded, former president Rajapaksa, whose political platform had come to be based on extreme Sinhala nationalism, visited them in the prison to show his solidarity with the ‘war heroes’ who saved the country. Newspaper articles appeared defending them and branding the journalist Eknaligoda as an LTTE supporter. A kind of political defence was being built, weaving a narrative that the ‘war heroes’ were doing their duty by arresting an LTTE informer. The extreme Sinhala nationalists led by the violent Bodu Bala Sena group launched a campaign defending the suspected army personnel.

January 25, 2016 was the rst day of the court hearings against the nine Army Intelligence officers who had been serving at the Giritale army camp, namely Lieutenant Colonel Shammi Arjuna Kumararatne, Lieutenant Prabodha Siriwardena, Lieutenant Priyantha Kumara, Rajapaksha Wadugedera Vinnie Priyantha, Ravindra Rupasena, Chaminda Kumara Abeyratne, Kanishka Gunaratne, Aiyyasami Balasubramaniam alias Ravi and Tharanga Prasad Gamage. On that day, an unruly gang of Buddhist monks and civilians literally invaded the court and made a statement saying that Eknaligoda was an LTTE informer and that the ‘war hero’ military personal should not be charged. The leader of the unruly gang, Ven. Galabodaatthe Gnanasara, threatened Sandya Eknaligoda while leaving the court after making his defamatory statement.

Soon after Ven. Gnanasara and other members of the gang were arrested and remanded for contempt of court. Immediately after this, mayhem occurred at the court, posters appeared against Sandya Eknaligoda and the lawyer who represent her interests. On February 9, 2016 the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) of cials informed the Homagama Magistrate that they had received evidence that Eknaligoda who had been detained at Giritale army camp, was blind-folded and taken to a location in Akkaraipattu [in the East] where he was killed.

The case continues.

WHERE IS RAMACHANDRAN?

Subramanium Ramachandran, a Jaffna-based freelance Tamil journalist, disappeared on February 15, 2007 in Jaffna.

According to reports, accompanied by a friend, he left the [private tuition] school he ran in Karaveddy at around 6 pm. on February 15. When they arrived at the Kalikai Junction military camp, soldiers ordered them to stop for questioning. Ramachandran was taken into the camp while his friend was asked to leave.

Asking the question: Where is journalist Subramanium Ramachandran? human rights defender Ruki Fernando wrote as recently as February 2016 that “according to an eye witness, on the day of the incident, Ramachandran was coming home after work. It was routine at that time to have a curfew imposed in Jaffna after 6 pm. On his way he was stopped at the Army camp at Kalikai junction, not far from his home in Jaffna. The eyewitness had seen some soldiers having surrounded him for questioning.”

Despite eyewitness accounts and information about the time and place of his disappearance, no investigation has been initiated even under the new government. The same fate has befallen the cases of a number of other killings of journalists. Sri Lanka still has a long way to go to end impunity, a goal which needs focused and continued advocacy.

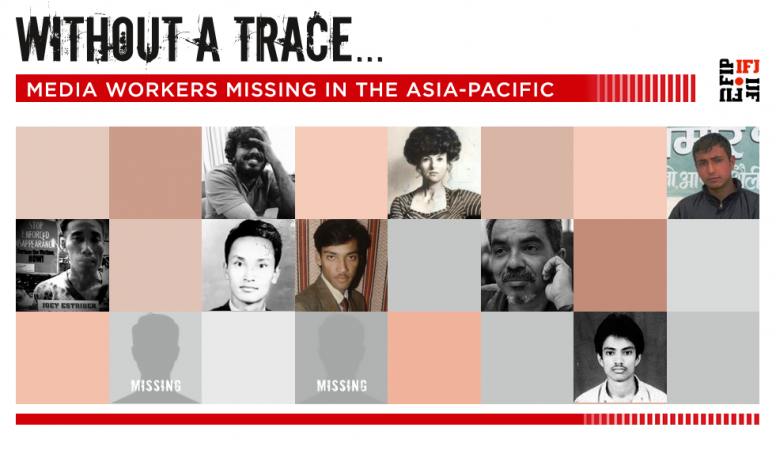

‘WITHOUT A TRACE’ CAMPAIGN FOR MISSING JOURNALISTS

Every time a journalist is abducted or disappears without a trace, the impact on press freedom can be devastating. There is no doubt that the insecurity and fear created by a disappearance ripples through the entire media community, which too often is the strategy of the perpetrators. Compounded with the failure of states to adequately prosecute and nd those responsible, it also supports and creates a climate of impunity for such atrocities. As such, the impunity on disappearances impacts more on freedom of media and there is a pressing need of strong advocacy and pressure on states to hold them accountable.

With this dismal backdrop, on November 16, 2015, the IFJ Asia- Paci c launched ‘Without A Trace: Media workers missing in the Asia-Paci c’, an online record highlighting the stories of 10 media workers who disappeared and currently remain missing in the region. Seven of those missing journalists are from South Asia – four from Nepal, three from Sri Lanka and one from Maldives. They are Minivan News journalist Ahmed Rilwan Abdulla (missing since August 8, 2014, Maldives), editor and publisher of Aaajko Samachar daily Prakash Singh Thakuri (missing since July 5, 2007, Nepal), Chitra Narayan Shrestha (missing since May 30, 2000, Nepal), managing editor of Janadesh weekly Milan Nepali (missing since May 21, 1999, Nepal), radio media staff Madan Paudel (missing since September 16, 2012, Nepal), and cartoonist Prageeth Eknaligoda (missing since January 24, 2010, Sri Lanka), Subramaniam Ramachandran (missing since February 15, 2007, Sri Lanka) and proof-reader Vadivel Nimalarajah of Uthayan newspaper (missing since November 17, 2007, Sri Lanka). Their cases are unsolved and investigation by authorities is far from satisfactory. The ‘Without A Trace’ campaign is a part of the ‘End Impunity’ campaign and the website, which has details of all missing cases and actions that people can take in order to urge the concerned government, can be accessed at ifj.org/missing

Resources

- IFJ South Asia Media Bulletin, February 2023 02/15/2023 Download

- IFJ South Asia Media Bulletin, January 2023 01/18/2023 Download

- Nepal Press Freedom report 2022 01/03/2023 Download