Access to Information

RTI in Sri Lanka: It took 22 years, and journey continues

14 Jul, 2016

Sri Lanka’s Parliament debated the Right to Information (RTI) bill for two days (23 – 24 June 2016) before adopting it into law. No member opposed it, although some amendments were done during the debate.

If that sounds like an easy passage, it was preceded by over two decades of advocacy with various false starts and setbacks. A large number of Lankans and a few supportive foreigners share the credit for Sri Lanka becoming the 108th country in the world to have its own RTI (or freedom of information) law.

How we reached this point is a case study of campaigning for policy change and law reform in a developing country with an imperfect democracy. The journey deserves greater documentation and analysis, but here I want to look at the key strategies, promoters and enablers.

The story began with the change of government in Parliamentary elections of August 1994. The newly elected People’s Alliance (PA) government formulated a media policy that included a commitment to people’s right to know.

But the first clear articulation of RTI came in May 1996, from an expert committee appointed by the media minister to advise on reforming laws affecting media freedom and freedom of expression. The committee, headed by eminent lawyer R K W Goonesekere (and thus known as the Goonesekere Committee) recommended many reforms – including a constitutional guarantee of RTI.

Sadly, that government soon lost its zeal for reforms, but some ideas in that report caught on. Chief among them was RTI, which soon attracted the advocacy of some journalists, academics and lawyers. And even a few progressive politicians.

Different players approached the RTI advocacy challenge in their own ways — there was no single campaign or coordinated action. Some spread the idea through media and civil society networks, inspiring the ‘demand side’ of RTI. Others lobbied legislators and helped draft laws — hoping to trigger the ‘supply side’. A few public intellectuals helpfully cheered from the sidelines.

Typical policy development in Sri Lanka is neither consultative nor transparent. In such a setting, all that RTI promoters could do was to keep raising it at every available opportunity, so it slowly gathered momentum.

For example, the Colombo Declaration on Media Freedom and Social Responsibility – issued by the country’s leading media organisations in 1998 – made a clear and strong case for RTI. It said, “The Official Secrets Act which defines official secrets vaguely and broadly should be repealed and a Freedom of Information Act be enacted where disclosure of information will be the norm and secrecy the exception.”

That almost happened in 2002-3, when a collaboratively drafted RTI law received Cabinet approval. But an expedient President dissolved Parliament prematurely, and the pro-RTI government did not win the ensuing election.

RTI had no chance whatsoever during the authoritarian rule of Mahinda Rajapaksa from 2005 to 2014. Separate attempts to introduce RTI laws by a Minister of Justice and an opposition Parliamentarian (now Speaker of Parliament) were shot down. If anyone wanted information, the former President once told newspaper editors, they could just ask him…

His unexpected election defeat in January 2015 finally paved the way for RTI, which was an election pledge of the common opposition. Four months later, the new government added RTI to the Constitution’s fundamental rights. The new RTI Act now creates a mechanism for citizens to exercise that right.

Meanwhile, there is a convergence of related ideas like open government (Sri Lanka became first South Asian country to join Open Government Partnership in 2015) and open data – the proactive disclosure of public data in digital formats.

These new advocacy fronts can learn from how a few dozen public spirited individuals kept the RTI flames alive, sometimes through bleak periods. Some pioneers did not live to see their aspiration become reality.

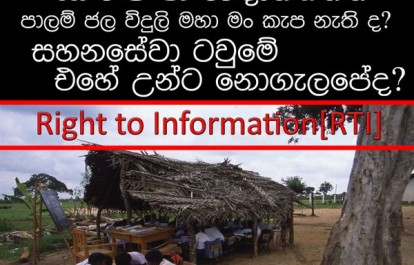

Our RTI challenges are far from over. We now face the daunting task of implementing the new law. RTI calls for a complete reorientation of government. Proper implementation requires political will, administrative support and sufficient funds. We also need vigilance by civil society and the media to guard against the whole process becoming mired in too much red tape.

RTI is a continuing journey. We have just passed a key milestone.

Science writer and columnist Nalaka Gunawardene has long chronicled Sri Lanka’s information society and media development issues. He tweets at @NalakaG.

Written By

Comments

Resources

- IFJ South Asia Media Bulletin, February 2023 02/15/2023 Download

- IFJ South Asia Media Bulletin, January 2023 01/18/2023 Download

- Nepal Press Freedom report 2022 01/03/2023 Download