SAMSN Blog

Blocking media access and rights in Northern Sri Lanka

18 Aug, 2021

The people of the remote island of Iranaitheevu in Northern Sri Lanka have an important story to tell the world. But journalists are being denied access, writes Ruki Fernando.

Article 14 (1) (a) of the Sri Lankan constitution guarantees freedom of speech and expression, including publication, and article 14 (1) (h) guarantees freedom of movement. While Article 15 specifies that these can be restricted for limited number of specified reasons on the condition that such restrictions are prescribed by law.

As a writer to newspapers and websites, as well as being an educator and speaker at forums related to rights and reconciliation, the necessity of access and travel for my work is a critical feature of my work. However, I have encountered arbitrary restrictions on movement several times in the past, mostly in the former war affected Northern and Eastern provinces. Such restrictions negatively impact my freedom of speech, expression and publication of critical information.

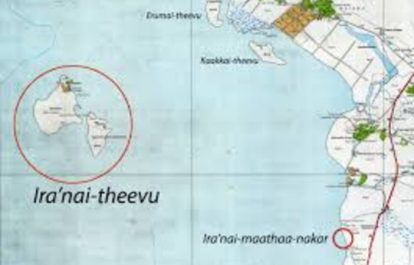

This year, I encountered fresh restrictions while trying to travel to Iranaitheevu, a remote island in the Kilinochchi district in Northern Sri Lanka. For about 25 years, during Sri Lanka’s war and even for nine years after the end of the conflict, its inhabitants were prohibited from residing there by the Sri Lankan Navy. It began when a 1992 navy offensive during the war forced all 650 of Iranaitheevu’s residents to flee by boat across the Palk Strait to Iranaimaatha Nagar on Sri Lanka’s mainland. This prohibition violated article 14 (1) (h) of the constitution which permits any person to reside in a place of their choice.

Despite continuous protests, discussions and communication with government officials and politicians over the years, Kilinochchi’s inhabitants were not allowed to return to their island, which remained occupied by the navy. Finally in April 2018, Iranaitheevu’s people re-claimed their homeland through a daring landing on the island.

Since then and despite various difficulties, people have resided there, engaging in fishing, religious services in their church and other activities related to civilian life. Iranaitheevu island comes under the Poonekary Divisional Secretariat and Kilinochchi District Secretariat, and government officials from these offices and others have been visiting the island, indicating the island is part of Sri Lanka, served by government officials and subject to the highest law in the country, the constitution.

I visited Iranaitheevu people during their displacement, I joined them when they re-claimed their island home and I have visited them ever since that time.

Earlier this year, the residents started to protest peacefully against the government announcement that Covid-19 dead from rest of country would be buried in Iranaitheevu. To learn more and write about this, two journalists from two national newspapers and I travelled overnight from Colombo and arrived in Iranaimathanagar, in Mulankavil around 9am on March 5 to travel to the Iranaitheevu island. Yet when we arrived, Navy personnel at a small camp checkpoint on the beach prevented us from boarding a boat to the island and informed us they had been instructed by their superiors that only residents were allowed to travel to the island and showed us a list of names given by a government official. All others, including journalists, were not allowed.

Straight away, I informed the Jaffna branch and head office of the Human Rights Commission and the District Secretary (Government Agent) of Kilinochchi about the unexpected restriction to our movements. The (HRCSL) promised to look into this, but the District Secretary said there was nothing she could do if we were stopped by the navy. She also said no travel restrictions to Iranaitheevu had been imposed by her or anyone working under her. I informed the Free Media Movement (FMM), which contacted the Minister of Mass Media and the Director General of the Government Information Department. Both said they didn’t know of any restrictions on journalists. By 4pm that day, we finally gave up and left. The villagers and Parish Priest of Iranaitheevu church, who were waiting for us to visit, were obviously disappointed and several villagers said that this undermined their protest as media could not cover it. I came to know that on the same day, as well as in previous days, the navy had stopped other journalists and activists from also visiting Iranaitheevu.

It’s not the first time that media and others have been blocked from visiting Iranaitheevu. On January 9, 2019, a media team from BBC and I were stopped by the navy at the same camp check point and prevented from boarding our boat. But that day, the HRCSL intervened swiftly and told us that the Area Commander for the Navy based in Thalaimannar assured there were no restrictions to travel to Iranaitheveu, and we were able to commence travel to the island within about an hour.

Even during Covid-19 related lockdowns and curfews, journalists have been allowed to visit public places all over the country and inform the public in Sri Lanka about the situation on the ground. But more than two months after the incident, my complaint to the HRCSL is still pending.

The HRCSL sought responses from the District Secretary and the Navy, and within days, forwarded me a written submission by the District Secretary confirming that there were no restrictions from her office. I’m not aware if the Navy has responded to the HRCSL. But the day we were waiting to travel to the island earlier this year, a navy spokesperson Captain Indika De Silva had confirmed to us that travel restriction to both Sinhala and English media. However on March 16, he told media that the navy had commenced an inquiry to investigate the matter seriously. We are yet to hear any outcome.

Freedom of movement is critical to exercising freedom of expression. These rights become even more important during times of crisis.

Ruki Fernando is a Sri Lankan writer, educator and rights activist. He is an executive committee member of IFJ affiliate, the Free Media Movement of Sri Lanka.

Comments

Resources

- IFJ South Asia Media Bulletin, February 2023 02/15/2023 Download

- IFJ South Asia Media Bulletin, January 2023 01/18/2023 Download

- Nepal Press Freedom report 2022 01/03/2023 Download