Right to Information

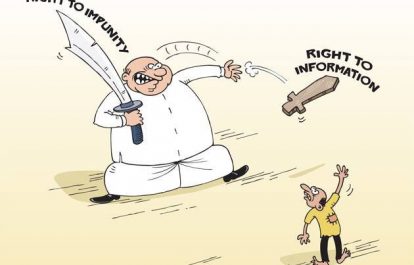

Sri Lanka’s RTI Law: Will the Government ‘Walk the Talk’?

03 Mar, 2017

Sri Lanka’s new Right to Information (RTI) Law, adopted through a rare Parliamentary consensus in June 2016, became fully operational on 3 February 2017.

From that day on, the island nation’s 21 million citizens could exercise their legal right to public information held by various layers and arms of government.

One month is too soon to know how this law is changing a society that has never been able to question its rulers – monarchs, colonials or elected governments – for 25 centuries. But early signs are encouraging.

Sri Lanka’s 22-year advocacy for RTI was led by journalists, lawyers, civil society activists and a few progressive Cartoon by Gihan de Chickera / Daily Mirror politicians. If it wasn’t a very grassroots campaign, ordinary citizens are beginning to seize the opportunity now.

RTI can be assessed from its ‘supply side’ as well as the ‘demand side’. States are primarily responsible for supplying it, i.e. ensuring that all public authorities are prepared and able to respond to information requests. The demand side is left for citizens, who may act as individuals or in groups.

In Sri Lanka, both these sides are getting into speed, but it still is a bumpy road.

In February, we noticed uneven levels of RTI preparedness across the 52 government ministries, 82 departments, 386 state corporations and hundreds of other ‘public authorities’ covered by the RTI Act. After a six-month preparatory phase, some institutions were ready to process citizen requests from Day 1. But many were still confused, and a few even turned away early applicants.

One such violator of the law was the Ministry of Health that refused to accept an RTI application for information on numbers affected by Chronic Kidney Disease and details about the treatment being given.

Such teething problems are not surprising – turning the big ship of government takes time and effort. We can only hope that all public authorities, across central, provincial and local government, will soon be ready to deal with citizen information requests efficiently and courteously.

Some, like the independent Election Commission, have already set a standard for this by processing an early request for audited financial reports of all registered political parties for the past five years.

On the demand side, citizens from all walks of life have shown considerable enthusiasm. By late February, according to Dr Ranga Kalansooriya, Director General of the Department of Information, more than 1,500 citizen RTI requests had been received. How many of these requests will ultimately succeed, we have to wait and see.

Reports in the media and social media indicate that the early RTI requests cover a wide range of matters linked to private grievances or public interest.

Citizens are turning to RTI law for answers that have eluded them for years. One request filed by a group of women in Batticaloa sought information on loved ones who disappeared during the 26-year-long civil war, a question shared by thousands of others. A youth group is helping people in the former conflict areas of the North to ask how much land is still being occupied by the military, and how much of it is state-owned and how much privately-owned. Everywhere, poor people want clarity on how to access various state subsidies.

Under the RTI law, public authorities can’t play hide and seek with citizens. They must provide written answers in 14 days, or seek an extension of another 21 days.

To improve their chances and avoid hassle, citizens should ask their questions as precisely as possible, and know the right public authority to lodge their requests. Civil society groups can train citizens on this, even as they file RTI requests of their own.

That too is happening, with trade unions, professional bodies and other NGOs making RTI requests in the public interest. Some of these ask inconvenient yet necessary questions, for example on key political leaders’ asset declarations, and an official assessment of the civil war’s human and property damage (done in 2013).

Politicians and officials are used to dodging such queries under various pretexts, but the right use of RTI law by determined citizens can press them to open up – or else.

President Maithripala Sirisena was irked that a civil society group wanted to see his asset declaration. His government’s willingness to obey its own law will be a litmus test for yahapalana (good governance) pledges he made to voters in 2015.

The Right to Information Commission will play a decisive role in ensuring the law’s proper implementation. “These are early days for the Commission which is still operating in an interim capacity with a skeletal staff from temporary premises,” it said in a media statement on February 10.

The real proof of RTI – also a fundamental right added to Constitution in 2015 – will be in how much citizens use it to hold government accountable and to solve their pressing problems. Watch this space.

Science writer and media researcher Nalaka Gunawardene is active on Twitter as @NalakaG. Views in this post are his own.

Cartoon by Gihan de Chickera / Daily Mirror.

Written By

Comments

Resources

- IFJ South Asia Media Bulletin, February 2023 02/15/2023 Download

- IFJ South Asia Media Bulletin, January 2023 01/18/2023 Download

- Nepal Press Freedom report 2022 01/03/2023 Download