India

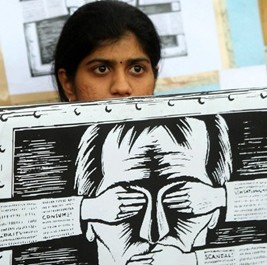

What Next For The Section 66A Cases?

26 Mar, 2015

The decision of India’s Supreme Court to uphold free speech and strike down draconian provisions of the amended Information Technology Act, 2000 is a victory for a concerted campaign by a cross-section of Internet users, civil liberties activists, internet freedom campaigners, lawyers and journalists. The campaign was conducted both online and offline, in courts and in seminars and discussions, commentary on social media networks and articles in the media.

It began in 2011, when the first rules under the amended IT act were notified and when a few lawyers and internet activists raised questions of the sweeping powers given by the act to police to arrest anyone who transmitted any electronic message that someone, somewhere could take offence to or claim to be annoyed or harassed by. Other pernicious provisions of the act included the 36 hours’ notice given to intermediaries to take down content that was reported to be offensive, widespread powers to monitor, intercept and block any communication that is seen to be against national security, stringent checks on cyber cafes and extremely invasive provisions on data security.

The amendment to the act itself comes in the wake of the heightened anxiety over terror attacks following the November 26, 2008 attacks in Mumbai. In a discussion in Parliament that barely lasted 15 minutes, the draconian provisions were pushed through, citing national security as a primary concern. But, as events that followed showed, the act allowed for a very wide net to be cast, compromising the security of ordinary citizens who used the Internet to comment on politicians, critique or satirise corruption, citizens who commented on inefficient traffic police and even students who spoke up against school authorities or politicians!

While the Supreme Court struck down today as unconstitutional the infamous Sec 66 A of the Information Technology Act, in a judgement of far-reaching implications, the question arises — what actually happens to all the cases lodged now? And the proceedings in various courts?

“What is the status of our case? Well, the matter is still being heard, all we get are adjournments after adjournments. We haven’t even got to the trial stage as yet!” – That was the response of KVJ Rao, the Air India officer who is one of the accused in a case under this law.

For all those accused for free speech violations under the draconian provisions of this section, which Justices J Chalameshwar and RF Nariman held were completely open-ended and undefined, the process had become a major part of the punishment for cases, lodged on specious charges of offensiveness, causing annoyance or harassment. But it was clear that the judgement would bring immense relief to those accused.

In 2008, sweeping amendments were made to the Information Technology Act, 2000, and the previous UPA government was strenuously criticised for a number of instances of the misuse of the act on free speech provisions. Interestingly, the NDA government was criticised for going soft on the issue when it came to power.

But the court categorically said that ‘an assurance from the present government that it would be administered in a reasonable manner’ cannot save the draconian section. “Governments may come and governments may go but Section 66A goes on forever. An assurance from the present government even if carried out faithfully would not bind any successor government,” the court said.

The court stated that it was ‘clear that not only are the expressions used in Section 66A expressions of inexactitude but they are also over broad and would fall foul of the repeated injunctions of this Court that restrictions on the freedom of speech must be couched in the narrowest possible terms’. The court also read down Sec 79 on intermediary liability to be effected only on a court order, upheld the blocking of content under Sec 69 of the Information Technology (IT) Act and struck down Sec 118 of the Kerala Police Act.

The judgment, which has examined three aspects of freedom of expression under Art 19 (1): discussion, advocacy and incitement, has held that the first two, however unpopular, are at the heart of Art 19 (1) and it is only in the third aspect of incitement, that the reasonable restrictions of Art 19 (2) will kick in. The judgement examines all the eight reasonable restrictions under this article and maintains that Sec 66 A is unconstitutional as these do not fall under the purview of any of the eight reasonable restrictions under Art 19 (2) of the Constitution.

The judgement, which held that Sec 69A and the Information Technology (Procedure & Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules 2009 was constitutionally valid, has read down Sec 79 to mean that due diligence of an intermediary would include a court order to remove or disable access to material that may attract reasonable restrictions under Art 19 (2).

The petition in the case decided today was filed by law student Shreya Singhal. It arose with the arrest of Shaheen Dhada and Renu Srinivasan, which had sparked nation-wide outrage and brought attention to the sweeping and arbitrary provisions of Sec 66A. While the two students had disabled their Facebook accounts as a result of the arrests, they did speak out against the arrests and came out strongly against any curbs on their freedom to speak. In a meeting organized by The Hoot’s Free Speech Hub in Mumbai University in 2013, Shaheen spoke to other students of her experience and urged them to continue to exercise their freedom of speech!

(The case against the two students was withdrawn after the Maharashtra government decided to drop charges. Shaheen Dhada graduated a couple of years ago and is now married. Her father, who was very supportive of his daughter, told The Hoot that he was very happy at the judgment and that the court had taken the right decision to uphold freedom of speech).

Since 2011, when the first cases under Sec 66 A began to be lodged, there have been a string of them. From the arrest of a professor of Jadhavpur University Ambikesh Mohapatra, for sharing a cartoon that poked fun at Trinamool Congress leader Mamata Banerjee, to a case against cartoonist Aseem Trivedi for his cartoons on corruption, and the case against two students in Palghar — Shaheen Dhada and Renu Srinivasan, for their Facebook posts on the city-wide shutdown following the death of Shiv Sena leader Bal Thackeray. There was the case against a young woman in Chandigarh who protested the Chandgarh Traffic police’s delay in following up on a complaint on her stolen SUV, the 20 days in jail that KVJ Rao and his colleague Mayank Sharma underwent after a union rival in Air India lodged a case under Sec 66 A against them for a Facebook post; and then there was the arrest of a businessman for tweeting about the son of then Union minister P V Chidambaram. In addition, students of schools in Lucknow and Baroda have been suspended and charged for writing facebook posts against their teachers and school authorities.

The list seems endless.

And yet, the process of justice in each of these cases, however absurd and baseless the charge of annoyance or harassment or offensiveness may be, has been a long and arduous one. Recently, the National Human Rights Commission has said that the West Bengal government must compensate Prof Mohapatra for jailing him and for the harassment he faced. But the West Bengal government has, till date, refused to acknowledge the harassment.

Of course, let’s not forget that in most of the cases, charges on the basis of other provisions of the Indian Penal Code and other laws are pressed on the accused. Indeed, in the recent judgement of the Bombay High Court on cartoonist Aseem Trivedi, the charge of sedition was set aside but other charges under the insult to national emblems act and the now ubiquitous Sec 66 A, are still prevalent.

For a law that was just barely four years old, it was an extraordinary unleashing of police powers against a range of ordinary users of the Internet of social media networks and websites who were just beginning to explore the powers of free expression online. Doubtless, the law enforcing machinery, which tried hard to cope with this, began to double its efforts to train police in cyber-crime. In Maharashtra, the Mumbai police launched a social media lab with much fanfare, announcing its plans to monitor all content on YouTube and other social media networks.

While, on the one hand, those accused under Sec 66 (A) were arrested and their acts criminalized, they were not the only ones who were criminalized. The worst aspect of this section was that it makes potential criminals of all users of electronic media. And that is what the judgment, so hearteningly acknowledges:

“Section 66A is cast so widely that virtually any opinion on any subject would be covered by it, as any serious opinion dissenting with the mores of the day would be caught within its net. Such is the reach of the Section and if it is to withstand the test of constitutionality, the chilling effect on free speech would be total.

Geeta Seshu is a Mumbai-based journalist, a member of the Brihanmumbai Union of Journalists and also the Consulting Editor of the mediawatch website The Hoot

Photo Credit: STRDEL / AFP

This article was originally published in The Hoot and can be found Here

Written By

Comments

Resources

- IFJ South Asia Media Bulletin, February 2023 02/15/2023 Download

- IFJ South Asia Media Bulletin, January 2023 01/18/2023 Download

- Nepal Press Freedom report 2022 01/03/2023 Download