SRI LANKA

Gargantuan Economic Crisis

A Buddhist monk takes part in a demonstration against the economic crisis at the entrance of the president’s office in Colombo on April 11, 2022. Sri Lanka’s Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa pleaded for “patience” as thousands continued to take to the streets to protest his family’s rule, with public anger at a fever pitch over the country’s crippling economic crisis. Credit: Ishara S. Kodikara / AFP

The severe economic crisis in Sri Lanka poses yet another challenge to a media barely recovering from the Covid-19 pandemic. The country’s economic crisis, due to indebtedness, deficit of foreign reserves and inflation has impacted every sphere of life in Sri Lanka.

The food inflation rate increased from 3 per cent in January 2021 to 12.8 per cent in October, 17.5 per cent in November, and 22.1 per cent in December. According to Sri Lanka Central Bank officials, it has printed 1.4 trillion Sri Lankan rupees (USD 3.962 billion) in 2021. In December, Fitch Ratings downgraded Sri Lanka’s sovereign rating to ‘CC’ from ‘CCC’, citing a growing risk of debt default in 2022.

A number of protests took place across the island, against daily power cuts and shortages of fuel and other essential items. On March 31, 2022, thousands of protestors gathered in front of the private residence of President Rajapakse located in the suburbs of Colombo demanding that the President to step down. The slogan #GotaGoHome rented the air. Police and military personnel blocked the roads leading to the president’s house and protestors were beaten and subjected to tear gas and 54 of them were arrested. Seven journalists who reported the incident were brutally assaulted by the security forces, including Sumedha Sanjeewa who was assaulted while in police custody.

The next day, the journalists who went to report from the protest site were intimidated and threatened by persons claiming to be from the President’s Security Division (PSD). On April 1, 2022, the President Rajapakse declared a state of emergency, arming the military with additional powers, leading to arbitrary arrests, detention and restrictions on fundamental rights. The next day, social media was blocked on the instructions of the Ministry of Defence (MoD), and curfew was declared in the Western Province where the country’s capital is located, to clamp down on the proposed nationwide protest. The curfew justified broad powers to arrest anyone on any public road or public area, without a warrant.

Despite the curfew, mass protests took place on the night of April 3, 2022, in multiple areas. Access to social media was restored on the same day, after media rights groups and others condemned the action and after the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka which investigated issued a statement pointing out that MoD does not have authority to block social media. On April 1, a young activist who was involved in the Facebook group ‘Go Home Gota’ that organised anti-government protests was allegedly abducted by the security forces and was later found to be in the detention of a Colombo Police station and released on bail on the next day after the incident. His arrest was based on the social media posts which police claimed to have caused “public unrest”.

Over the year, the Covid-19 pandemic and ensuing health regulations became a pretext for the authorities to restrict citizens’ rights, including that of freedom of expression. A series of arrests, interrogations and investigations into social media content was observed.

While the Covid-19 context contributed to an increase in the consumption and usage of social media and internet platforms, digital growth declined as compared with the previous year. In 2020, active social media users increased by 23.4 per cent, while there was only a 3.8 per cent increase in 2021. Internet users increased by 7.9 per cent in the year 2020, while this figure was only 4.9 per cent in 2021. The year also saw increasing reprisals, state surveillance and regulation of the digital media landscape.

At the same time, the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights were arbitrarily used to arrest and detain those who expressed dissent. Disciplinary codes for government officers were used to restrict them from expressing opinions in the media and social media. The Prevention of Terrorism (Temporary Provisions) (Amendment) Bill was published in the gazette on January 27, 2022, and passed by a majority vote in Parliament on March 22. The Human Rights Watch termed the amendments “a legal black hole”.

Plans are afoot to revive the defunct Press Council Act No 5 of 1973 despite strong opposition from media rights groups. Laws are being drafted in relation to Buddhist canonical texts to restrict their interpretations into a single official version. New restrictions were introduced about Islamic publications. The Voluntary Social Services Organizations, Registration and Supervision (VSSO) Act No 31 of 1980 is being amended with a view to strengthen national security and regulation of civil society. It is likely that the NGO secretariat that had long been functioning under the Ministry of Defence would be armed with more powers to supervise and regulate civil society organisations.

The Sri Lankan media industry has long been polarised in terms of political affiliations in media ownership. According to the Media Ownership Monitor Sri Lanka, 54.8 per cent television media outlets, 45.59 per cent radio channels, and 79.4 per cent newspapers are owned by politically-affiliated entities, including more than 30 per cent media entities that are directly owned by the state.

Sri Lanka, as a post war country with ever rising trends of ethnonationalism and intolerance towards religious, ethnic and sexual minorities along with patriarchal oppression, has long unresolved challenges that include discrimination and sexual harassment of female journalists.

While the state has not taken any steps to ensure the independence of the state media and growing number of violations and restrictions related to freedom of expression and other rights, the discourse of media ethics that was effectively brought forward by the government seemed to be a potential strategy to repress media freedom and dissent, rather than a genuine attempt to broaden the rights and freedoms in the media landscape.

Shaky media industry

During the Covid-19 pandemic, existing issues in the media industry such as poor wages and working conditions of media workers rapidly deteriorated. Facing safety concerns a more than a year after the pandemic, the Sri Lanka Working Journalists Association (SLWJA) in May 2021 wrote a letter to the Minister of Mass Media, requesting media workers to be provided with minimum hygiene equipment such as face masks and hand sanitisers, highlighting recent trends of pay cuts, loss of employment and other financial vulnerabilities especially faced by freelance journalists.

“Many media outlets have fired those who worked on a contract basis and as freelancers for their organizations, claiming that they were making a loss. The monthly income of many freelance journalists has fallen below the 15,000 LKR (around USD 75) limit due to reductions of allowances”, said the SLWJA. It further noted that many journalists faced difficulties in repaying the ‘Media Aruna’ loan given to journalists by the Ministry of Mass Media and Information.

The economic crisis has also affected functioning of the media. The Upali newspapers that publish The Island and Divaina English and Sinhala daily newspapers halted their Saturday publications in March 2022 due to the prevailing print material shortage. Both daily Divaina and Island newspapers reach a small percentage of the print media audience. Divaina daily has 1.3 per cent print audience concentration, while The Island has only 0.1 per cent print audience concentration.

Other national dailies have been forced to reduce pages after costs rose by more than a third in the past five months and because of difficulties securing supplies from abroad. Energy shortages have affected all sectors of the economy, the media included. The economic crisis is only adding to an already beleaguered media industry.

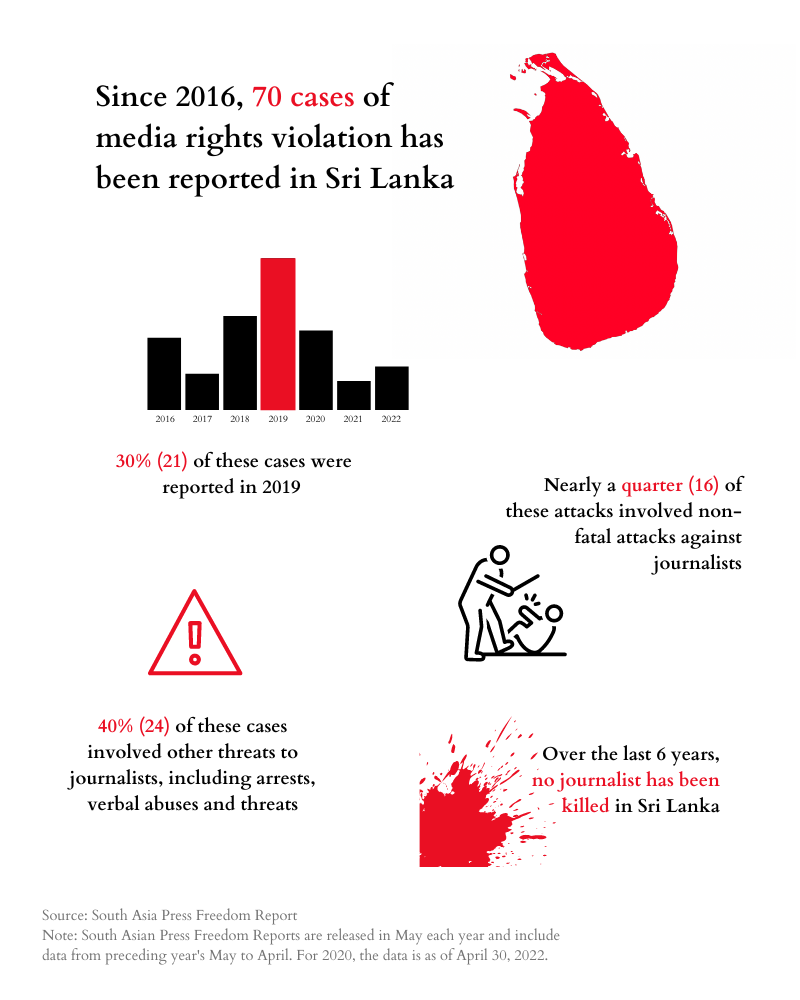

Media Rights Violations

Killings

Arrests

Sandya Eknaligoda, the wife of cartoonist Prageeth Eknaligoda, has her hair shaved near a Hindu temple in Colombo on January 25, 2022, to seek divine help to trace her husband, who was abducted in 2010. Credit: Ishara S. Kodikara / AFP

On March 30, 2022, thousands of protestors gathered in front of the private residence of President Rajapakse located in the suburbs of Colombo demanding that the President to step down.

Safety off and online

According to the data available at INFORM Documentation Centre in Colombo, at least five journalists were arrested in 2021, at least eight were physically assaulted, while another two journalists were tortured. Six out of eight journalists who were physically attacked were from the Northern and Eastern Provinces – the former war zones in Sri Lanka. Out of the five journalists arrested, two were from former war affected Jaffna district, while three were from Colombo district, the country’s capital.

In 2021, 13 journalists in 11 separate incidents were summoned and interrogated by the police in relation to their reporting. In September 2021, in another case relating to a trade scam expose, attempts were made to summon six journalists from multiple media institutions and to record statements from others.

In April 2021, in the case of journalist Malika Abeykoon, another freelance journalist arrested while covering a protest by health workers, was tortured in police detention and presented before the magistrate court in Maligakanda along with a false medical report that claimed he had no injuries. Upon Abeykoon proving otherwise, the magistrate ordered another medical examination. According to reported information, no action has been taken against the police for submitting a false medical report.

The attack on the residence of prominent television journalist Chamuditha Samarawickrema in Piliyandala by unidentified assailants on February 14, 202, was a blatant attack on a journalist critical of the government. The Federation of Media Employee’s Trade Unions (FMETU), the Free Media Movement (FMM), and the Sri Lanka Working Journalists Association (SLWJA), urged the authorities to expedite their investigation and bring justice to the perpetrators.

Digital security threats and state authorities confiscating and accessing digital equipment belonging to journalists was a consistent pattern in terms of number of arrests and interrogations. This was evident in the arrest of Keerthi Ratnayake who was arrested in August 2021 and detained until February 2022 by Sri Lankan Police under the draconian Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) after him warning the Indian embassy in Colombo about a possible terrorist attack. His laptop, mobile phone and several pen drives were confiscated. Another police team also visited Ratnayake’s house in Kandy without a warrant where they confiscated several mobile phones and pen drives, while another team also visited one of his friends’ house further searching for digital equipment. Ratnayake is former military officer and an investigative journalist who covers Defence and crime related news for the London based website Lankaenews run by an exiled journalist.

Batticaloa-based Tamil journalist Selvakumar Nilanthan who was interrogated by the Terrorism Investigation Division of the Sri Lanka Police was also asked to reveal passwords and give access to his email, Facebook and WhatsApp accounts, bank accounts and other personal details. In March 2021, an Opposition Parliamentarian Harin Fernando alleged that the government had begun to use Pegasus spyware that has been infamously known for surveillance of human rights activists and others. These trends indicate that digital security is becoming a vital aspect of the safety of journalists and media workers in Sri Lanka as never before.

The IFJ’s Union to Union Project that seeks to strengthen and unionise young journalists in Sri Lanka was successfully carried out by the Free Media Movement, culminating in the setting up of the Digital Media Movement and the drafting of a Code of Ethics for digital media in December 2021.

Not yet on par

While accurate statistics of gender representation in the media labour force are unavailable, female journalists at the entry level are almost equally represented in many media institutions.

However, too many female journalists leave their careers at an early stage as opportunities for career growth are limited. Women journalists routinely highlight issues related to sexual harassment, wage inequality, systemic sexism and discrimination. One senior female journalist currently working freelance said that the reason to quit her job was the recruitment of an inexperienced male journalist at a higher wage than hers, despite her experience and seniority in the organisation. This discriminatory culture also repeats in women’s inclusion in trade unions where their participation in the decision making is limited, and their presence is often included as tokenistic. There is almost no discussion on the concerns on diverse sexual orientations and gender identities and gender expressions in the media workforce. The lack of effective policies, structures or mechanisms that address gender discrimination, sexual harassment and other issues in the media became apparent during the #MeToo movement in Sri Lanka.

In June 2021, a number of women journalists spoke about their experiences of sexual harassment in newsrooms in a belated #MeToo movement. The disclosures began after journalist Sarah Kellapatha tweeted that a male colleague had threatened to rape her when she worked at an unnamed newspaper from 2010-17. She added, “It was almost impossible for any female to wear a dress to work, without having to endure salacious remarks from male colleagues about their legs and bodies in general, or they’d utter a loud “sexy”. It was always very uncomfortable.”

Former journalist Sahla Ilham said she “was sexually abused by a famous editor in a now defunct newspaper. It was to the point that he was controlling my family to stay quiet.” Several young female journalists tweeted that they had been sexually harassed and abused by senior male journalists. One said that a hidden camera was found in the female washroom of a Sinhala language newspaper office. The management merely removed the camera but did not conduct any inquiry into the incident. Such impunity and lack of action to penalise sexual harassment could be one of the major reasons that forces lot of female journalists drop their careers at an early stage.

Media Minister Rambukwella initially stated that the government would launch an investigation into the sexual harassment accusations, he later changed his stance to insist on formal complaints, not social media posts.

In June 2021, a number of women journalists spoke about their experiences of sexual harassment in newsrooms in a belated #MeToo movement.

Sri Lanka’s government ordered an investigation into sexual harassment in the media after a number of #MeToo allegations from female newsroom staff in June 2021.

Evolving media

According to the Digital 2022 Sri Lanka country report, only 36.6 per cent social media users are female. Increased online harassment and conventional patriarchal attitudes that discourage women from using social media could be possible reasons behind such a trend. It is important to note that 55 per cent of the total 10,890 complaints received to Sri Lanka Computer Emergency Readiness Team (Sri Lanka CERT) in the year 2020 are related to the abusive content and cyber harassment involving social media. Though no gender disaggregated data has been provided, it is apparent that women, girls and LGBTIQ persons often become targets of online abusive content.

There is also a gender and urban-rural gap in both digital literacy and computer literacy. In 2020, 47 per cent of females and 53 per cent males were digitally literate, while 66 per cent of the urban population, 48 per cent of rural population and 26 per cent of tea estate population were digitally literate. Lack of access to digital and computer equipment among the estate sector could be attributed to intergenerational poverty, social exclusion and discrimination faced by estate sector communities.

The poor digital infrastructure especially in terms of affordability and internet signal coverage in rural areas of Sri Lanka attracted national and international attention in the context of Covid-19 as schools shifted online. The disparities in education increased along with the Covid-19 pandemic. It was a common sight to see children climbing trees and rocks in search of internet signals.

Inequalities in access to digital resources curtails certain populations from the internet, social media, restricting their access to information. In a context where mass media ownership is hugely controlled by party political actors and corporate interests, such a curtailment of information also results in other problems including generational underdevelopment. Additionally, a fault in the international submarine cable SMW4 slowed down internet speed in Sri Lanka from January 2022, and regular daily power cuts caused by the fuel shortage in March 2022, further reduced internet access to many users.

Despite challenges, in the last few years the digital media landscape grew in Sri Lanka. Some YouTubers, including some individual journalists, media companies and many entertainers started reaching a wider audience. The platform TikTok started becoming more popular in recent years, with young users effectively including socio political economic issues in the largely entertainment focused platform. Conversely, TikTok was also a platform where women and LGBTIQ persons were subjected to many forms of online harassment, hate speech and other reprisals for their gender, gender identity, expression and sexuality. This was especially visible in case of local language content.

Legal noose

Arrests and detention of writers, journalists, whistle-blowers and activists under charges of ‘terrorism’ using repressive laws such as draconian Prevention of Terrorism Act occurred throughout the report period. The poet Ahnaf Jazeem who was arrested under Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) in May 2020, was granted bail only in December 2021, after almost 19 months of detention during which he was not allowed to meet his lawyer or family members. Authorities alleged that his work contained ‘extremist’ ideas, a claim refuted by independent literary experts. In September 2021, a petition was made on behalf of Ahnaf Jazeem to the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention.

Batticaloa-based journalist Murugupillai Kokulathasan working for Battinews who was arrested in November 2020 under the PTA is still under detention. He was arrested for allegedly promoting the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), the proscribed former rebel group in Sri Lanka through his Facebook posts. His arrest is based on the captioned photographs he had shared on Facebook showing Tamil civilians commemorating their loved ones killed during the civil war. Though the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka (HRCSL) called for an inquiry in 2021, no progress has been made.

In a few instances, journalists were not allowed or restricted from attending events of public interest such as court hearings, political events, and local council meetings due to Covid-19 related restrictions. In the North and East, journalists were either not allowed or delayed at military checkpoints despite confirming their identity as journalists. In September 2021, the Daily Mirror reported that journalists found it difficult to ask critical questions or follow up questions with government ministers and officials during press and cabinet briefings held online. The article further alleged that certain journalists are not even allowed to raise questions if their media institution is considered to be hostile to the government, and in some cases only pre-planned questions by politically aligned persons are answered.

In a number of cases, journalists and others who expressed dissenting opinions were subjected to surveillance, summoning and interrogation by police officers under the Terrorism Investigation Department (TID) and Criminal Investigation Department (CID). In September 2021, after reporting on the ‘Garlic scam’, a corruption case in purchasing garlic stocks in Lanka Sathosa – the government retail network, six senior journalists including several newspaper editors were summoned to the CID. In addition, CID officials visited the Lankadeepa newspaper head office expecting to interrogate the journalists who reported on the issue. After media rights groups and activists decried the move, interrogation of journalists was stopped with the intervention of Prime Minister Rajapakse.

Quest for justice

Toward the end of civil war in Sri Lanka in 2009 and the post-war period, the country witnessed a wave of killings of journalists and media workers. According to Journalists for Democracy in Sri Lanka, 43 journalists and media workers were killed between 2004 and 2010. In addition, assaults and disappearances and attacks on media houses regularly dotted the media landscape.

Thirteen long years have passed since the murder of senior journalist and editor Lasantha Wickrematunge. Several attempts to get justice both inside and out of the country have failed. In a step forward, the People’s Tribunal on the murders of journalists in Hague together with Center for Justice and Accountability (CJA) will hear the case of Lasantha Wickrematunge. The Government of Sri Lanka has been officially notified about the Prosecution’s indictment by the independent Permanent People’s Tribunal (PPT) and invited to exercise its right of defence during the hearing.

The report of the controversial Presidential Commission of Inquiry (PCoI) to Investigate Allegations of Political Victimization was tabled in Parliament in March 2021. The report recommended acquittal of the suspects in emblematic cases including at least three ongoing legal cases pertaining to crimes against journalists (i) the assassination of Sunday Leader newspaper editor Lasantha Wickrematunge in January 2009, (ii) the abduction and torture of Nation newspaper deputy editor Keith Noyahr in May 2008 and (iii) the abduction and disappearance of journalist Prageeth Eknaligoda in January 2010.

In January 2021, another Special PCoI was appointed to implement the recommendations made by the PCoI on Political Victimization. In July 2021, the Cabinet of Ministers presented a parliamentary motion to withdraw the cases against some of their supporters based on the recommendations made by the PCoI on Political Victimization. Significantly, the key investigator in these emblematic cases Inspector of Police Nishantha De Silva fled the country in the end of year 2019, while the Former Director of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) Shani Abeysekara who led investigations got arrested in year 2020, was granted bail in June 2021. These interventions in the justice mechanisms, intimidation of prosecutors, and witnesses in the emblematic human rights cases including crimes against journalists was a major pattern throughout the year 2021.

In a number of cases, journalists and others who expressed dissenting opinions were subjected to surveillance, summoning and interrogation by police officers under the Terrorism Investigation Department (TID) and Criminal Investigation Department (CID).

Journalists and well-wishers light candles on the grave of slain journalist Lasantha Wickrematunge in Colombo on January 8, 2021, on the twelfth anniversary of his death. Credit: Lakruwan Wanniarachchi / AFP

The legal environment

The draconian Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), Act No 48 of 1979 was used to interrogate, arbitrarily arrest and detain journalists, writers and to obtain involuntary confessions after torturing the detainees. The Act allows detention of suspects for unspecified “unlawful activities” for a period of three months, extendable up to a period of 18 months. The role of judiciary in the case of PTA is often limited to rubber stamping the detention order issued by the Minister of Defence. In March 2021, UN human rights experts including OHCHR issued a statement for an immediate moratorium on the use of Sri Lanka’s Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) and urged the Government of Sri Lanka to substantively review and revise the legislation to comply with international human rights law.

Ironically, Section 3 of International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) Act No 56 of 2007 that deals with “advocating national, racial, or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence” has been misused to arrest and detain writers and other, as an offence under the section 3 of ICCPR Act is “non-bailable”, except through a High Court. The case against the writer Shakthika Sathkumara, who was arrested in April 2019 continued until February 2021 when he was acquitted and released of all charges, related to his short story ‘Ardha’. The story was published in an anthology of short stories after his release. Subsequently, Sathkumara filed a case (pending in court) demanding compensation for the damages caused by his arbitrary arrest and detention.

In March 2022, Sri Lanka’s parliament passed the Personal Data Protection Bill, amid concerns about its impact on media reporting and severe restrictions on the right to information.

Transparency International Sri Lanka issued a statement saying that the Bill should address three concerns: (i) Severe impact on journalism, (ii) Data Protection Authority having wide powers and lacking independence, (iii) impact on right to information. The Press Institute and seven media rights groups and trade unions raised serious concerns regarding the Bill in relation to infringement and restrictions on media freedom and right to information. As pointed out by the media rights groups, restrictions on “special categories personal data” which include “financial data, personal data relating to offences, criminal proceedings and convictions” could severely limit the journalistic reporting especially on issues such as corruption. The bill also contains a section on ‘official secrecy’ that prohibits state officials from releasing said ‘personal information’ that may result in severe restrictions on the right to information.

The Act also empowers the minister to appoint any government institution as the Data Protection Authority (DPA), raising questions about the independence of the institution. The DPA also has the power to conduct inquiries against those who violate the Personal Information Act and order to pay financial penalties up to 10 million LKR. In a context where many independent newspapers run on a low budget, such a penalty could easily bankrupt them. Though the Sri Lanka Young Journalists Association (SLYJA) filed a Fundamental Rights (FR) Petition against the bill, it was unsuccessful due to the technical error of delayed submission. Following the unsuccessful FR petition, SLYJA wrote a letter to the UN High Commissioner on Human Rights Michelle Bachelet requesting her attention on the data protection bill that compromises rights of the journalists.

In April 2021, the Cabinet approved the proposal to enact a new bill to review and regulate Buddhist publications. The proposed law seeks to counter ‘distorting the pure Buddhism and Buddhist traditions’ through printed and digital publications and publications that contain material related to Buddhist teachings, the character of the Buddha, or which have any relevance to Buddhism are to be reviewed, regulated, and censored by a committee appointed by the government. The proposed law will bring severe challenges to writers, artists, academics and others who write about religion and run the risk of accusations of ‘defamation’ of Buddhism. Seen along with the March 2021 restrictions on the import of Islamic publications and books ostensibly to “prevent the import of extremist materials that are harmful to the reconciliation of the country’, spaces for free expression are clearly shrinking.

Media rights groups had opposed the government proposal to restructure the Press Council Act No 5 of 1973, a repressive law that has been detrimental to media freedom. The Free Media Movement in March 2021 issued a statement highlighting several issues with the Press Council, namely: (i) It is not an independent institution as the President has powers to appoint, remove, decide on salaries, and to reappoint its members; (ii) Minimal representation of the media sector in the Press Council; (iii) Certain offences under the Press Council Law restrict media freedom. Eg. reporting on cabinet proceedings without approval; (iv) Absence for provisions for appeal; (v) Powers to hear cases on contempt against the Press Council; (vi) Code of ethics prepared not in consultation with the media institutions; and (vii) Introducing offences that could result in imprisonment of journalists. In January 2022, cabinet approval was granted to appoint a committee to obtain public views to reform the Press Council as a Tribunal for journalists and media institutions covering print, electronic and new media and to do other relevant reforms. In February 2022, the Media Minister called for public opinions on the reform process, while it is not clear whether the said committee has been yet appointed.

Meeting international obligations

At the 49th session of the Human Rights Council held between 28 February–1 April 2022, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights presented a follow up report on the human rights situation in Sri Lanka. It mentioned that “OHCHR continues to receive allegations of intimidation, monitoring and surveillance by security services against… journalists” and others, while the government has stressed that all such complaints should be submitted to the national mechanisms. Referring to prolonged arrest of the journalist Murugupillai Kokulathasan who has been detained over 15 months in relation to the alleged photos of LTTE leader appearing in his social media, report mentioned that the government has shared with OHCHR a directive issued by the Inspector General of Police dated October 23, 2021, providing guidance on restricting the use of the PTA and exercising greater discretion in evaluating cases such as, possession of pictures. The cases against those who were previously arrested continues, and interrogation and harassment of individuals based on such accusations are still reported, while the number of such new arrests have reduced since October 2021.

While the government attempted to reform the Prevention of Terrorism (Temporary Provisions) Act No. 48 of 1979 (PTA), the changes that were brought were inadequate. In January 2022, the government gazetted amendments to the PTA). In February 2022, the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) stated that “the Sri Lankan Government must repeal the draconian Prevention of Terrorism Act, as a new set of proposed reforms are woefully inadequate and overlook the most egregious provisions of the legislation.” In March 2022, UN human rights experts also called for an immediate end to the PTA and urged the Sri Lankan government to substantively review and revise a counter terrorism legislation to comply with international human rights law.

Activists aligned with ‘Journalists for Rights’ hold a candlelight vigil in Colombo on January 31, 2022 to pay tribute to the journalists allegedly killed while on assignment. Credit: Ishara S. Kodikara / AFP

Solidarity in tough times

The Black January campaign demanding justice on attacks and killings of journalists under the theme ‘Ensure justice to journalists murdered, enforced disappearance, assaulted and threatened’ was conducted online in January 2022 due to the Covid-19 situation.

The FMM organised an event to discuss the impact of the ICCPR Act and the PTA Act on media freedom; safety and security of Tamil journalists and surveillance of and reprisals on investigative journalists. A group of media organisations also held a protest in Colombo demanding justice and an end to impunity for crimes against journalists. Alongside, Journalists for Rights and Young Journalists Association also organised another protest event commemorating Black January in Colombo under the theme ‘Let’s not forget’ demanding justice for the crimes against journalists. The Sri Lanka Working Journalists Association (SLWJA) with the Jaffna Press Club commemorated Black January by displaying protest boards in front of the Jaffna Main Bus Stand.

Sandya Ekneligoda, wife of journalist Prageeth Ekneligoda who disappeared after being abducted in January 2010 organised a religious event at Modara Goddess Kali temple demanding justice from god in the absence of any justice from the legal system. She shaved her head asking for divine intervention to punish the perpetrators. In 2017, Sandya Ekneligoda was awarded International Woman of Courage by the US State Department.

Attempts to mobilise continued through the year. In the wake of Sri Lanka’s belated #Metoo movement, female journalists discussed about sexual harassment they have experienced while working in the media industry. Initial discussions took place on the media ethics and rights in relation to LGBTIQ community both in mass media and social media. The discussions were organised by several NGOs, media rights activists with the participation of journalists.

In September 2021, a local politician was removed from his position based on the information obtained through the Right to Information Act which proved that the politician had bribed the voters Moneragala District during the election. This landmark verdict obtained against an elected local councillor is a step towards pressing for public accountability.

Survival and solidarity

In the context of Covid-19 and the economic crisis, media freedom in Sri Lanka faced many challenges during the year. The economic crisis mainly caused mainly by indebtedness and foreign currency deficit has also impacted the media industry, causing joblessness, and loss of income mainly among the freelance journalists and contractual employees. The rising cost of living and power cuts has also impacted working conditions of media workers, and equity in digital media access. Despite local and international pressure, the government has failed to make adequate progress on the human rights situation in Sri Lanka including on press freedom.

A number of interventions that address both structural and attitude changes are required to ensure press freedom. Government accountability and ensuring justice in relation to crimes against journalists, ensuring press freedom and safety and protection of journalists. This includes ensuring their employment security and labour rights standards and the independence of both public and private sector media. All are vital to improve the media freedom in Sri Lanka, in the absence any willingness or commitment from the government or other responsible parties.

In contrast, the state authorities seemed more focussed on repression and regulation of media freedom with their keen interest in purchasing surveillance software, and confiscation of digital equipment belonging to journalists, and other forms systematic surveillance, and the use of repressive laws and policies to arrest, detain and prosecute journalists and others who raise their dissenting voices. Despite these challenges, journalists’ rights advocates made their presence felt, in street and online protests as well as petitioning government and courts, in a display of solidarity in these challenging times.