INDIA

A Climate of Fear

India’s Congress party workers are detained by security personnel in New Delhi on July 20, 2021, as they take part in a demonstration the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s alleged surveillance operation using the Pegasus spyware. Credit: Prakash Singh / AFP

The year 2021, like the past seven, continued to test the media in India like never before, with government pressure on journalists at its highest levels since India’s tryst with the 21-month Emergency of 1975-77. Some media and journalists stood tall, but many succumbed to the pressure.

A fear psychosis gradually grew with the ‘taming’ of the media through a lethal cocktail of the use and misuse of laws: the Disaster Management Act during the pandemic; Section 124A (sedition) and Section 153A (promotion of communal hatred) of the Indian Penal Code or the draconian Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA); the National Security Act; the defamation law, and the Information Technology (Guidelines for Intermediary and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021. Additionally, raids by the Enforcement Directorate and Income Tax departments on media houses and journalists were designed to intimidate. And if these were not enough, surveillance of journalists is the latest in the government’s tool bag to intimidate critics, and clampdown on free speech and independent journalism.

India is alleged to be among 50 countries that used Pegasus, the Israeli spyware to snoop on over 50,000 people. The data analysed by The Wire, part of the international collaborative investigation titled “Pegasus Project”, shows that most were targeted between 2018 and 2019, in the run-up to the general elections. Forensic tests confirmed that a number of individuals had indeed been spied upon via the Pegasus software. At least 40 journalists are said to be among 300 others, including a Supreme Court judge, opposition leaders, ministers, constitutional authorities, activists, and former election commissioners, who were under the government’s watchful gaze. Amidst denials by the government, Israeli sources revealed that the software is sold solely to law enforcement and intelligence agencies of “vetted governments”. In July 2021, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of India, NV Ramana, in response to petitions challenging illegal surveillance said, “allegations are serious if the reports are correct…The truth has to come out”. It set up an independent three-member expert committee, reasoning: the State cannot get “a free pass every time the spectre of ‘national security’ is raised”.

With the state aggressively intruding upon constitutionally guaranteed rights, the highest court of the land made significant interventions through the year, giving hope that the judiciary might uphold the sacrosanct right to freedom of speech and expression and freedom of the press.

Defining limits

The apex court has also taken up arguments against the archaic sedition law that makes criticism of the government an act ‘against the nation’. The cases tie up journalists and others in a legal nightmare and allow prolonged detention without trial, an easy way to intimidate and harass critics. Final hearings regarding the constitutional validity of the sedition law are expected to be taken up on May 5, 2022.

In October 2021, former Supreme Court judge Rohinton Nariman exhorted the apex court to let citizens “breathe more freely” by repealing the sedition law and the offensive provisions of the UAPA. “There is a chilling effect on free speech. If you are booking persons, including journalists, under these laws which come with large sentences and no anticipatory bail, people would not speak their mind.”

Two cases of sedition against the media shone a much-needed spotlight on the issue. Battling for over a year since such a charge was levelled by the Himachal Pradesh police against him for one of his YouTube shows, senior journalist the late Vinod Dua finally got a reprieve. The top court quashed the charges on June 2, 2021. Equally significant was what it said: “Every journalist will be entitled to protection under the Kedar Nath Singh judgment on sedition.” According to the 1962 landmark verdict, “mere strong words used to express disapprobation of the measures of the government with a view to their improvement or alteration by lawful means” does not amount to sedition.

In the second case, the apex court stayed the sedition charges against two Telugu news television channels TV 5 and ABN Andhrajyoti on May 31, 2021. Noting that the cases appeared to be an attempt to “muzzle media freedom,” the court said, “It is time we define the limits of sedition…particularly in the context of the right of the electronic and print media to communicate news, information and the rights, even those that may be critical of the prevailing regime in any part of the nation.”

Over the period under review, the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) ruling at the centre and some states used the lens of Hindu nationalism to paint critics of the government as “anti-national” or anti the Hindu majority. Many media houses with business interests tied to extensive government advertising – more so since the pandemic – put themselves on mute or simply played along to enhance the government’s nationalist/majoritarian narrative, often targeting journalists, progressives, minorities, and independent thinkers.

This was particularly so with television news channels which, instead of holding power to account, have been used to intimidate, harangue and attack the opposition, liberals, and critics of the ruling party, as ‘traitors’, ‘anti-Hindu’ and ‘against national interests’. Only a few, especially digital news platforms, have tried to hold their own. Amid this polarisation, the credibility of the media among the people took a beating. In the milder first Covid-19 wave too, the 21-day lockdown from March 24 to April 14, 2020, without adequate prior notice resulted in immense trauma for thousands of daily-wage earning migrant workers, many of whom took the desperate step of trekking back to their homes on foot. Many did not make it alive. This lockdown was dovetailed by more and lasted till May 31, before phase wise unlocks began. However, the mismanagement of the devastating second Covid-19 wave, which ravaged India in April and May 2021, witnessed a larger section of the media playing its assigned role: speaking truth to power.

The mishandling of the pandemic was highlighted through social media which shared horrific stories – of overflowing hospitals, people scrambling for oxygen, scores of funeral pyres burning in parking lots and on riverbanks and even corpses floating in rivers – that even a pliant media could ill-afford to ignore.

However, the revival of independent journalism during this second wave was forgotten in the heat and dust of five State Assembly elections in Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Manipur, Goa and Punjab in early 2022. Media houses were easily identified as taking sides given the structure of corporate ownership, and the majority aiding the ruling party and those who did not fall in line were penalised, in many cases using the law.

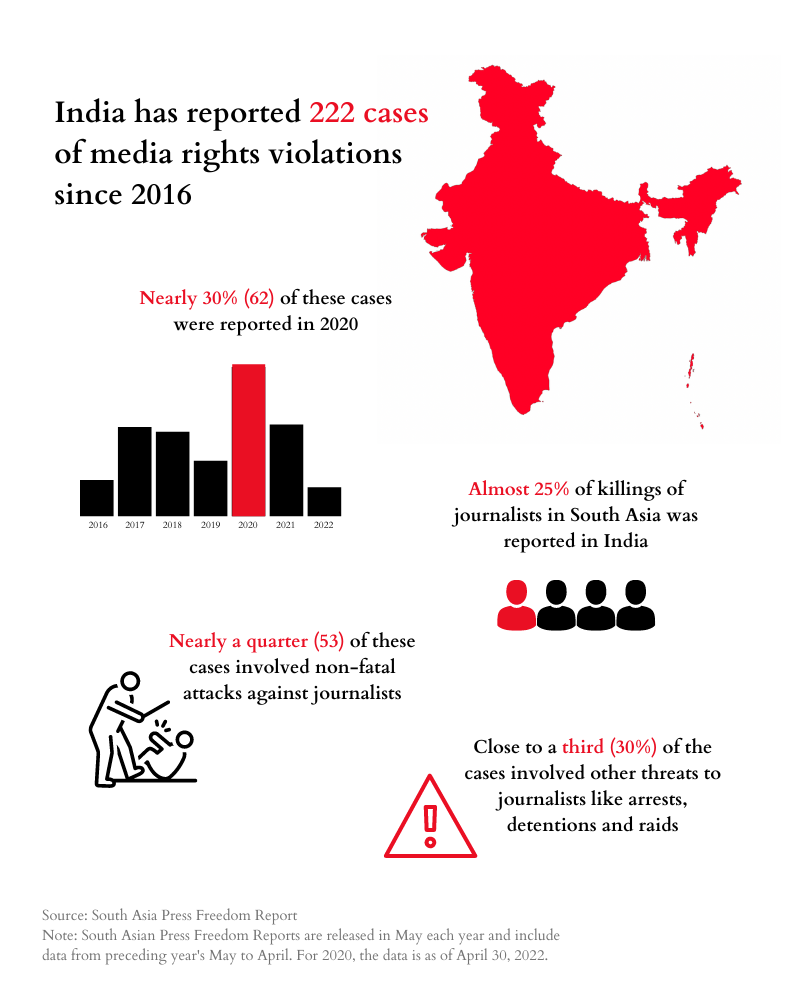

Media Rights Violations

Killings

Arrests

India is alleged to be among 50 countries that used Pegasus, the Israeli spyware, to snoop on over 50,000 people.

“It is time we define the limits of sedition…particularly in the context of the right of the electronic and print media to communicate news, information and the rights, even those that may be critical of the prevailing regime in any part of the nation.”

Afghan nationals residing in India and supporters of the Afghan Refugee Women’s Association demand better rights for women in Afghanistan in New Delhi on October 30, 2021. Credit: Sajjad HUSSAIN / AFP

Judicial checks

The IT (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021, put in place in February 2021, seem to have done more harm than good. Not only on the home front has there been an outcry, but three UN special rapporteurs on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association, and on the right to privacy have firmly said that the Rules in their current form, do not conform with international human rights norms.

In a report in June 2021, they further noted: “We would like to recall that restrictions to freedom of expression must never be invoked as a justification for the muzzling of any advocacy of multiparty democracy, democratic tenets and human rights.” The government through its permanent mission to the UN in Geneva responded: “The concerns alleging potential implications for freedom of expression that the new IT Rules will entail are highly misplaced,” and these are “designed to empower ordinary users” of social media.

On August 14, 2021, the Bombay High Court stayed the operation of Rules 9(1) and 9(3) dealing with an adherence to a Code of Ethics as ‘prima facie the Code is an intrusion of the petitioners’ rights of freedom of speech and expression.’ Rule 9(3) explains The Quint: creates a three-tier grievance redressal mechanism to deal with complaints that a digital media publisher has violated the Code of Ethics: the publisher themselves, a self-regulatory body of digital media publishers, and an inter-ministerial committee set up by the Centre. Any person can file such a complaint and can take it up the tiers if dissatisfied with the response received. This “effectively gives the central government, through the inter-ministerial committee in tier 3, oversight over all material published by digital media houses, and allows it to impose sanctions on media houses which it believes to have violated the Code of Ethics.”

The case is one of many filed by several digital media organisations and journalists across the country. It is being viewed as a major victory for digital news media, given that these appear to be on the government’s target list of ‘censorship’. Four months later, the Madras High Court restrained the Union government from taking any coercive action against digital media firms under the code of ethics. The Kerala High Court too passed a similar order.

While on the one hand the government is finding ways to check critical digital news media, on the other it seeks monopolies of Facebook, Twitter, and Google to be supportive of the ruling dispensation. According to a four-part series of articles reported by The Reporters Collective and Ad Watch, published by Al Jazeera in March 2022, the Facebook advertising platform “systematically undercut political competition” in India, giving the BJP an “unfair advantage” over other political competitors in the elections. The stories examined 500,000 political advertisements placed on Facebook and Instagram between February 2019 and November 2020 — a time when India’s 2019 General Elections and nine State Assembly elections were held – and found how these boosted the BJP’s campaigns.

Digital Growth

India has the second largest number of internet users behind China, numbering 600 million. Many journalists are using YouTube and Facebook to build their own audiences, and the numbers using social media platforms have risen since the onset of Covid-19. The pandemic hit the employment market, like all the other sectors. Hundreds of journalists faced job losses, salary cuts, and furloughs, etc. Media houses lost the traditional revenue of private advertisements and were wholly dependent on government advertisements and were thus under pressure. Many legacy media houses shut down editions, pruned staff, and chose to stay on its right side. In this scenario, digital media saw a steady rise.

In its December 2021 report on the media and entertainment industry, the Confederation of Indian Industry and Boston Consulting Group (BCG) pointed out: “The share of traditional media is slowly declining with increased digital adoption.” But there is still high headroom for penetration with only 54 per cent of Indian households with a paid television connection and for many households, television continues to be the centre of the home and a significant part of family time. Marketing spends moved towards digital media and away from traditional segments like print, radio and to some extent television. A greater reliance on subscription and other paid options as well as the development of a credible digital business model is going to be inevitable for these traditional media segments.”

The writing is on the wall. A shift from an advertisement-based revenue model to a subscription-based model is necessary. And though these are difficult times, and India has started its journey late, the subscription-based model is evolving, with the pandemic forcing a change in business strategy.

Lives lost

Other than the economic brunt, hundreds of journalists across the country died and suffered multiple cases of post-pandemic challenges resulting in medical, social, and financial losses. The work pressure, with a number of media houses and offices in districts preferring staff to come to the office rather than working from home, neither providing protective kits nor insurance coverage, saw too many journalists risk their lives in the line of duty.

Estimates of the number of media workers who lost their lives differ. According to a study by the Delhi-based Institute of Perception Studies, over 300 journalists lost their lives due to the virus since the pandemic started. On average, three journalists died every day in April 2021. In May, this average climbed to four per day. The second wave not only claimed the lives of several senior journalists but also killed many others working in districts, towns, and villages across the different Indian States. The Network of Women in Media, India says it has documented more than 600 covid-related deaths since the second wave engulfed India in April 2021.

The Indian Journalists Union (IJU), an affiliate of the IFJ and The Editors Guild of India (EGI), among other associations had written to the Union government demanding that as the journalists were carrying out their duties for a better-informed public, they too be declared ‘frontline workers’ and be given the Covid-19 vaccination on priority basis. This demand was not met at the central level. However, as the pandemic raged, several states declared journalists as frontline workers to be prioritised for vaccinations on World Press Freedom Day, May 3, 2021. These were Bihar, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Punjab, Tamil Nadu, Uttarakhand, West Bengal, and several states in the Northeast including Arunachal Pradesh and Tripura. Some also announced financial aid to families of journalists who died due to Covid-19.

At the same time, the state machinery misused the Disaster Management Act to monitor the media and mute critical voices. Fear of reprisal has forced media houses and journalists to impose self-censorship. As a result, investigative journalism too took a beating. Consequences of disobeying would add to the hardship as the authorities equipped themselves with tools to book a journalist for ‘fake news’ or disinformation.

While on the one hand the government is finding ways to check critical digital news media on the other, it seeks monopolies of Facebook, Twitter, and Google to be supportive of the ruling dispensation.

Many legacy media houses shut down editions, pruned staff, and choose to stay on its right side. In this scenario, digital media saw a steady rise.

Supporters of India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) celebrate outside the party office in Lucknow on March 10, 2022, as votes are counted for the Uttar Pradesh state assembly elections. Credit: Sanjay Kanojia / AFP

Attacking dissent

The cases of intimidation and harassment of the journalists across the country reveal that the BJP-ruled States were front-runners in their attempts to silence dissent and independent reportage.

The state of Uttar Pradesh was a particularly difficult one for journalists. On June 16, 2021, Ghaziabad police filed First Information Reports (FIRs) against three journalists – Washington Post columnist Rana Ayyub; freelance journalist Saba Naqvi; co-founder of fact-checking website Alt News, Mohammed Zubair; and news Website The Wire for ‘provoking communal sentiment’ by tweeting a video showing an elderly Muslim-man being beaten up by a group of men. The EGI, IJU and the association of digital news media, DIGIPUB condemned the police action and demanded the withdrawal of cases.

In the same month journalist Pateshwari Singh, Bureau Chief of Bharat Connect and city reporter for Jan Sandesh Times in Ayodhya was beaten by unidentified men for writing an article against a local BJP MLA. The men in an SUV rammed into his two-wheeler and then thrashed him. The IJU and NUJ(I) demanded that an FIR be lodged against the men as well as the MLA. On July 5, Shajahanpur district police filed an FIR against three journalists for reportage on a woman petitioning the Delhi High Court that she was being harassed by the media after converting to Islam.

Physical assaults were also rife. Krishna Tiwari, a local journalist from Unnao district was beaten by the chief development officer as well as by some ‘BJP workers’ and journalist Raman Kashyap was among five persons mowed down by the convoy of Ashish Mishra, the son of the Minister of State of Home, Ajay Mishra Teni. The convoy drove through a crowd of farmers protesting against the three contentious agriculture laws in October 2021. Though Ashish Mishra was released on bail in February 2022, the Supreme Court appointed Special Investigation Team (SIT) challenged the bail, calling it a ‘planned conspiracy’.

Siddique Kappan, a Delhi-based journalist with Malayalam news portal Azhimukham and the secretary of the Kerala Union of Journalists languishes in jail since he was arrested by the Mathura police on October 5, 2020, and charged later under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act. His fault — he had like other journalists gone to cover the Hathras tragedy of alleged gang rape and murder of a young Dalit woman.

The Tripura police in November 2021 booked 102 social media account holders under the stringent UAPA for protesting against communal violence after a mosque and a few houses and shops were reportedly vandalised in Panisagar district. Journalist Shyam Meera Singh was booked under the Act just for tweeting ‘Tripura is burning’. The Supreme Court on February 7, 2022, asked the State Government to stop harassing people for their tweets. The EGI sent a three-member fact-finding team from November 28 to 1 December 2022. The EGI concluded: “The Tripura Police and the administration have displayed a lack of professionalism and integrity in dealing with the communal conflict and with those reporting on the issue. This makes them complicit in the growth of muscular majoritarianism that subverts democratic institutions”.

In Manipur, this systematic intimidation of the media has been no different. The arrest of an outspoken journalist Kishorechand Wangkhem on two occasions is a case in point. The first was in 2018 for criticising the BJP government which had controversially come to power even though it was not the single largest party in a hung Assembly. The second time was in 2021 after the state BJP president, Saikhom Tikendra Singh, succumbed to Covid and Wangkhem remarked that the man ought to have known that cow dung and urine are not remedies for Covid. He was arrested under sedition charge and spent three months in prison before a court order freed him.

On November 14 and 15, 2021, two Delhi-based women journalists of HW News Network, Samriddhi Sakunia and Swarna Jha were detained at the Assam border at the request of the Tripura police for their reportage and tweets on the communal friction in Tripura. They were charged under various sections of the Indian Penal Code on the complaint of the member of the Visha Hindu Parishad (VHP) a local Hindu organisation for allegedly ‘maligning’ the image of Tripura government and VHP.” After being arrested in Tripura, the two were released on bail.

On September 9, 2021, miscreants ransacked the office of Pratibadi Kalam, in the state capital Agartala, and three journalists were injured. It turned out that the newspaper’s editor and publisher lodged an FIR alleging that after a BJP rally, its workers attacked and ransacked his office and burnt cars and two-wheelers parked outside.

Assam too had its share of violations. On December 4, 2021, Silchar-based journalist Anirban Roy Choudhury who runs Barak Bulletin, a news portal in the Cachar district of Bengali-speaking Barak Valley, was booked under the sedition law over an alleged “objectionable” article. Journalist and RTI activist Avinash Jha was found dead on November 12, 2021, his body burnt and thrown on the roadside near his village in Bihar’s Madhubani district. Associated with a local news portal, Jha exposed many illegal medical clinics being run in the district and the misdeeds of contractors and others.

In Haryana, journalists who were reporting and filming a demolition drive in Khori Gaon in July 2022, in Faridabad district, were threatened and manhandled by the police.

States ruled by Opposition parties also witnessed violations of journalists’ rights. In Andhra Pradesh, Chennakeshavalu, of local TV news channel EV5, was stabbed to death in Nandyal, allegedly by a suspended police constable about whose illegal activities the journalist was doing a story. On March 2, 2022, the Raipur police in Chhattisgarh arrested journalist Nilesh Sharma of magazine and web portal India Writers for allegedly breaching pace and “promoting enmity or hatred between classes” and immoral trafficking for his satirical criticism of the Congress government.

In Odisha, on February 18, 2022, four journalists were attacked during elections at Binjharour area when reporting on booth capturing. Rohit Biswal was killed by an improvised explosive device, allegedly planted by Maoist insurgents on February 5, 2022, while covering the polls.

Trickle down

Not only individual journalists, but media houses too came under the scanner. Raids by Enforcement Directorate or Income Tax authorities on critical media groups seemed aimed at intimidation: fear psychosis from the top will trickle down to the bottom.

The offices of Dainik Jagran, one of the largest Hindi media groups, were raided at around 30 locations on July 22, 2021, for alleged ‘tax evasion’, but the targeting seemed more linked to the media house highlighting Covid-19 mismanagement. Critical media, particularly during the second wave of Covid, was increasingly coming under attack by the government. This trend follows raids on other media outfits such as The Quint in October 2018 and NewsClick in February 2021 and again on September 10, 2021, A similar raid was carried out at the offices of news portal Newslaundry, with an earlier visit having been paid in June 2021. These websites are known to be critical of the central government.

Likewise, on January 31, the Information & Broadcasting Ministry revoked the Malayalam news channel MediaOne’s licence and banned its telecast on the basis of an intelligence report asking the Ministry of Home to deny ‘security’ clearance, without giving reasons. However, the Supreme Court on March 15, 2022, stayed the Ministry’s directive “till further orders.”

The Information & Broadcasting Ministry in another controversial decision tweaked the Accreditation Guidelines for Central Accreditation (2022) issued by the Press Information Bureau. Accreditation can be revoked if a journalist is “charged with a serious cognizable offence”, or “acts in a manner which is prejudicial to sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of State, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency or morality or in relation to contempt of court, defamation or incitement to an offence”.

The EGI, Press Club of India, IJU and Indian Women’s Press Corps, among others, protested against the changes made. The EGI termed ‘bizarre’ the provision that merely being charged was a ground for the cancellation of accreditation. It added that apart from it being vague, there was also no adjudicating authority in case of revocation and furthermore, changes, if any, should have been made only after consultations with stakeholders.

On November 14 and 15, 2021, two Delhi-based women journalists of HW News Network, Samriddhi Sakunia and Swarna Jha were detained at the Assam border at the request of the Tripura police for their reportage and tweet on the communal friction in Tripura.

Raids by Enforcement Directorate or Income Tax authorities on critical media groups seemed aimed at intimidation: fear psychosis from the top will trickle down to the bottom.

Student activists march in Kolkata on January 31, 2022, demanding the re-opening of education institutions across the state of West Bengal, closed to curb a rise in Covid-19 infections. Credit: Dibyangshu Sarkar / AFP

Institutions undermined

The steady erosion of democratic institutions during the year represented another attack on press freedom.

The Press Council of India, mandated to safeguard press freedom and uphold the best standards of journalism in print media, has had no head since November 2021 and since the government has not moved on the process of appointment. The work of the quasi-judicial body to hear grievances against the press and by the press is at a standstill.

In another setback to media’s watchdog role, journalists’ entry into Parliament House and its press galleries restricted due to the Covid pandemic has not been restored to previous levels. The Press Club of India, the Editor’s Guild of India, the Indian Journalists Union, and Indian Women’s Press Corp were among others who protested on December 24, 2021, demanding that the government remove the restrictions and allow Parliament proceedings to be scrutinised by the media to ensure accountability.

The fight back

While struggles to reduce the gender gap are ongoing, women journalists are engaged in a huge battle online. The attempt to silence them has viciously grown – from trolling, branding them as ‘anti-national’, and spewing sexist remarks and morphed photos, to putting them on online ‘auction.’

Online apps such as ‘Bulli Bai’ and ‘SulliDeals’ on the Github platform, that profiled Muslim women activists, journalists, analysts, artists and researchers were taken down after vigorous protests. These cases test the tricky balance between free expression online, government regulation and the ‘freedom’ to bully and abuse vulnerable sections of society.

‘Bulli Bai’ came up in January 2022 and appears to be an offshoot of ‘SulliDeals’, which first surfaced in July 2021. (Bulli/Sulli is derogatory slang for Muslim women). The Internet Freedom Foundation called the fake online auction of almost 100 Muslim women a “blatant violation of their data security and privacy rights.”

The Print quoted political analyst Zainab Sikandar Siddiqui, whose picture was on ‘SulliDeals’, saying: “Unfortunately cyberbullying is so common that it has become a “norm…. Sexualisation and targeting of women happen across the board, but it is definitely disproportionate for Muslim women. Especially more so in these politically polarised times in the country when ‘Hindu vs Muslims’ is a common theme.”

Online abuse of women journalists from marginalised sections was especially severe. Dalit Meena Kotwal, founder of online news channel The Mooknayak was mercilessly trolled since December 2021. Rape threats and death threats over the phone from men who claimed to belong to Hindu nationalist outfits such as Bajrang Dal, Karni Sena and Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) reportedly told her that she would meet the same fate as murdered journalist Gauri Lankesh. On February 3, 2022, the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders and other UN experts expressed their concern to the Government of India over the inaction in this serious case.

Likewise, Washington Post columnist Rana Ayyub who has been repeatedly trolled and labelled ‘anti-national,’ has been battling with the Enforcement Directorate in a money laundering case. After she was prevented from leaving the country, she approached the Delhi High Court on April 4, 2022, which upheld her petition and allowed her to travel abroad. The UN Special Rapporteurs on right to freedom of opinion and expression Irene Khan, and Mary Lawlor, on the situation of human rights defenders, have written to the Indian authorities saying: “Relentless misogynistic and sectarian attacks online’ against Rana must be promptly and thoroughly investigated by the Indian authorities and the ‘judicial harassment against her brought to an end at once.’

In regard to making media workplaces safe for women, a trial court in Goa on May 21, 2021, acquitted then editor-in-chief of Tehelka, Tarun Tejpal of all charges levelled against him including wrongful confinement, sexual harassment and rape against his female colleague. Even as the case has gone on appeal to a higher court, the case has triggered important conversations on workplace safety.

Keep us online

India continued to hold the dubious reputation of being what the Software Freedom Law Center, India termed the ‘internet shutdown capital’ of the world, as per its tracking of shutdowns.

In the period under review, internet services were restricted, among others, in all districts of Kashmir on January 26 (Republic Day) and in September following the death of separatist leader Ali Shah Geelani. There was a two-day shutdown in Itanagar district of Arunachal Pradesh following a call by a youth organisation declaring a State-wide bandh against the government not fulfilling its electoral promises; in December 2021, mobile internet and bulk SMS were shut down for 12 hours in Mon district of Nagaland after violence broke out in protest against the botched up Army raid in which eight civilians were killed; and in October 2021, the Uttar Pradesh government shut down internet services in Lakhimpur Kheri and Sitapur districts after violence broke out following the mowing down of four people by Union Minister of Home’s son cavalcade during a farmers protest against controversial agriculture laws. Then in September 2021, the Rajasthan government suspended internet and SMS services in five districts as a means to curb cheating during the Rajasthan Teacher Eligibility Test.

Shutdowns were used supposedly to maintain law and order. However, in December 2021, the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Information Technology in its report “Suspension of Telecom and Internet Services and its Impact”, said that while there is a thrust on digitisation, frequent suspension of the internet on flimsy grounds ‘is uncalled for and must be avoided’.

The committee, headed by Congress MP Shashi Tharoor, was of the firm opinion that it was imperative to define the ‘parameters and a robust mechanism is put in place at the earliest to decide on the merit or appropriateness of telecom/internet shutdowns” Moreso, as frequent internet shutdowns and suspension of telecom services did impact ‘life and liberty’ of the citizens.

Suspension of telecom services/internet greatly affects the local economy, healthcare services, and freedom of press and education, among others it said and added that internet is of immense importance in the present digital era… it’s the lifeline which is propelling businesses and services, permitting students to enrol for an important examination, and enabling home delivery of essentials and aiding freedom of the press.”

The committee also drew the government’s attention to the fact that as per the Cellular Operators Association of India (COAI), telecom operators reportedly lose IDR 24.5 million (more than USD 300,000) per hour in every Circle Area where there is a shutdown or throttling. Thus, other businesses which rely on the internet could lose up to 50 per cent of the aforementioned amount, adding that as per newspaper reports, India lost USD 2.8 billion in 2020 to internet shutdowns.

In its response to the committee, the Ministry of Home Affairs has explained that public safety and public emergency, which are often used to justify the suspension of such services in an area are not defined under Section 5(2) of the Indian Telegraph Act, and thus it is left to the “appropriate authority to form an opinion” on whether an event threatens public safety and emergency warranting an internet ban in an area.

Online apps such as ‘Bulli Bai’ and ‘SulliDeals’ on the Github platform, that profiled Muslim women activists, journalists, analysts, artists and researchers were taken down after vigorous protests. These cases test the tricky balance between free expression online, government regulation and the ‘freedom’ to bully and abuse vulnerable sections of society.

A lock hangs at the gate of the closed Kashmir Press Club building in Srinagar on January 18, 2022, after it was forcibly shutdown following a raid by armed police. Credit: Tauseef Mustafa / AFP

Kashmir’s media crisis

The media in the Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir (J&K), especially in the Kashmir Valley is slowly being “choked” mainly because of “the extensive curbs imposed by the local administration”, concluded a three-member Fact Finding Committee of the Press Council of India (PCI). The report, handed over to the PCI on March 8, 2022, has neither been debated nor adopted in the Council due to lack of an official meeting.

The report enumerates the struggles and challenges faced by the journalists in J&K from various positions, despite the claim of the Union Home Ministry that Kashmir is on the ‘path of development’ after the abrogation of Article 370 in August 2019. Intimidation, harassment, detention by the police, manhandling by security forces during military operations, and unfriendly policies of the administration were rife.

Frustration and pain poured out before the PCI Committee: “The Police department is in overdrive mode to issue a summons, lookout notices for journalists, many are arrested, there is an atmosphere of fear.” “I was summoned by the state C.I.D. for some innocuous tweets. They told me the police were preparing a background note on all journalists. But the tactics were humiliating. I was summoned dozens of times, sometimes late at night. This created a social problem for me and my family in the locality I lived.” “In 2016, I had gone to visit my uncle in Pakistan. Can I not have relatives in Pakistan? But I am repeatedly questioned: Had you gone to Pakistan?” So severe has been the harassment that many journalists have felt compelled to leave J&K for safer havens

The authorities interviewed included: Inspector General of Police Vijay Kumar, Divisional Commissioner Pandurang Pole, Lieutenant Governor Manoj Sinha and former Chief Minister and PDP chief Mehbooba Mufti (on whose complaint “…the freedom of expression had been virtually guillotined”) the PCI committee was formed.

The PCI committee also said journalists it met, particularly in the Kashmir Valley, were sharply divided on their approach to government pressures. While most felt that the government and security agencies had trampled on the freedom of expression, some felt the government did not interfere with their rights so long as they kept away from reporting and commenting on ‘anti-national’ themes.

The new year began on a terribly wrong note for the journalist community. Their representative body, The Kashmir Press Club (KPC), with a membership of 300-odd, which has been vocal on media issues and harassment of journalists, was suddenly taken over by the J&K Estate department on January 15, 2022. Within 24 hours a group of journalists arrived at the KPC office during weekend curfew, took it over by appointing themselves as a ‘new body’, and locked the Club for a week in the presence of police and paramilitary personnel. Thereafter, the local administration issued a statement saying that considering the ‘de-registration’ of the KPC and the faction fight, the club premises had been taken over by the J&K Estates Department, the original owner of the property. The move led to outrage not just in the Valley but among national and international organisations, such as the International Federation of Journalists, the EGI, Press Club of India, IJU. Expressing solidarity with the KPC and 11 journalist organisations in the Valley, they condemned the takeover as it was yet another attempt to silence critical voices.

Harass and detain

The past year, scores of journalists have had to suffer detention and investigations: Fahad Shah, editor of The Kashmir Walla is languishing in jail since his arrest on March 14 this year – his fourth arrest in past 40 days since February 4. Sajad Gul, a freelance journalist who contributes to news online websites The Kashmir Walla and Mountain Ink, was arrested by police on January 5 for posting a video of women protesting against the killing of a Lashkar-e-Toiba (LET) commander. Earlier in October, he was among others who were questioned such as Majid Hyderi, another freelance journalist for his social media posts, including those related to separatist leader Syed Ali Shah Geelani and Muharram and further questioned on his source of income. Salman Shah, the editor of the weekly digital magazine Kashmir First, and Mukhtar Zahoor, a photojournalists and stringer for BBC, were respectively detained for questioning in police stations for their whereabouts on September 1, 2021 the day Geelani died. Suhail Dar, of The Kashmiriyat and Maktoob Media, was detained and moved to Anantnag jail on charges of disturbing public peace.

Earlier in September, the houses of four journalists were searched and the journalists taken for questioning: Mir Halal, of TRT world; freelance journalist Shah Abbas; Azhar Qadrio, of Showkat Motta, former editor-in-chief of The Narrator; were searched by the J&K police and called to the Kothibagh, Srinagar for questioning on grounds of alleged involvement with ‘Kashmirfight Blog’. Photojournalists were thrashed by a J&K police officer in Srinagar while covering a Muharram procession on August 18, 2021. A week before, Aadil Farooq Bhat of CNS News Agency was detained in Makkah Market in a search operation near Lalchowk, Srinagar and freelance journalist Majeed Haidari was questioned after he tweeted it was a ‘fake encounter’.

The list is long. Concern over the situation in J&K was expressed by the UN Special rapporteur on promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, Irene Khan, and Elina Steinert, vice-chair of the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention. In a document dated June 3, 2021, they sought a response from the Centre about the measures taken to ensure that journalists were able to work in a safe environment in J&K and respond within two months. In the meantime, they urged “all necessary interim measures be taken to halt the alleged violations and prevent their re-occurrence and in the event that the investigations support or suggest the allegations to be correct, to ensure the accountability of any person(s) responsible for the alleged violations,” The report cited examples of The Kashmir Walla editor, Fahad Shah, independent journalists Auqib Javeed and Sajad Gul, and The Kashmiriyat editor Qazi Shibli. Aasif Sultan, of the Kashmir Narrator, arrested in August 2018 under the UAPA and other anti-terror laws, was finally granted bail on April 5, 2022, only to be rearrested under the Public Safety Act.

Inspector General of Police (Kashmir), Vijay Kumar, admitted to the Council team that from 2016 till mid-October 2021, 49 cases had been registered against journalists. Among these, eight journalists were charged under the stringent Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 17 registered as criminal intimidation, and 24 journalists were booked for extortion and other crimes.

Normal lines of communication between the local administration and media have been disrupted because of the former’s suspicion that a large number of local journalists are sympathizers of the militants’ cause. Additionally, the news media has been severely disrupted in the region due to the ongoing conflict, and sources of advertising are slowly withering away. Print media especially with its large overhead costs is barely sustainable anymore. The 2022 advertisement policy hammers another nail in its coffin by selectively giving advertisements based on the ‘line’ and nature of newspapers coverage.

The Valley is witnessing a steady growth of digital media, and the new media policy has earmarked 40 per cent of funds for it. However, there are ‘ifs and buts’. On the one hand, the policy says political affiliation or editorial policies of the newspaper, publications, and journals should not be taken into account while releasing ads, but on the other, “DIPR shall not release advertisements to such newspapers…which incite or tend to incite communal passions, preach violence, violate broad norms of public decency or carry out any acts of propagating any information prejudicial to the sovereignty and integrity of India.”

In recent months, the DIPR has suspended advertisements to 26 publications of the 259 in Jammu and 17 of the 166 in Kashmir, including Greater Kashmir, Kashmir Reader, and the Urdu Kashmir Uzma, known for their ‘anti-establishment’ stand. Additionally, issuing of accreditation cards to journalists stopped with effect from March 31, 2020, and no fresh IDs or any other form of press recognition have been issued. This is despite the fact that press accreditation in a conflict zone is critical for safe passage to carry out authentic reporting.

The administration is yet to recognise that a free and independent media in the Valley could aid in ushering in ‘normalcy’ that it has been striving for.

Course correction

In sum, the state’s actions are having a chilling effect on the fourth estate in the world’s largest democracy. The media is not the enemy of the state. Instead, it must be helped to grow. The Indian media is going through severe trials and tribulations, battling deep economic crises as well as political polarisation, all of which threaten media freedom. The deep divisions need to be addressed and institutions strengthened in order for media to play its assigned role in society.

The media in the Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir (J&K), especially in the Kashmir Valley is slowly being “choked” mainly because of “the extensive curbs imposed by the local administration”.

Normal lines of communication between the local administration and media in Jammu and Kashmir have been disrupted because of the former’s suspicion that a large number of local journalists are sympathizers of the militants’ cause.