BHUTAN

Hollowed Out Media

Women wait in a queue to cast their votes outside a polling station in Thimphu on January 9, 2024. Bhutan began voting on January 9 in general elections with parties vowing to tackle economic challenges, calling into question its longstanding policy of prioritising “Gross National Happiness” over growth. Credit: Money Sharma / AFP

Since the advent of democracy in 2008, every institution in Bhutan has grown stronger and more mature, but the Bhutanese media has been hollowing out year by year. This has led to a gradual deterioration in the substance, strength and effectiveness of the media in Bhutan.

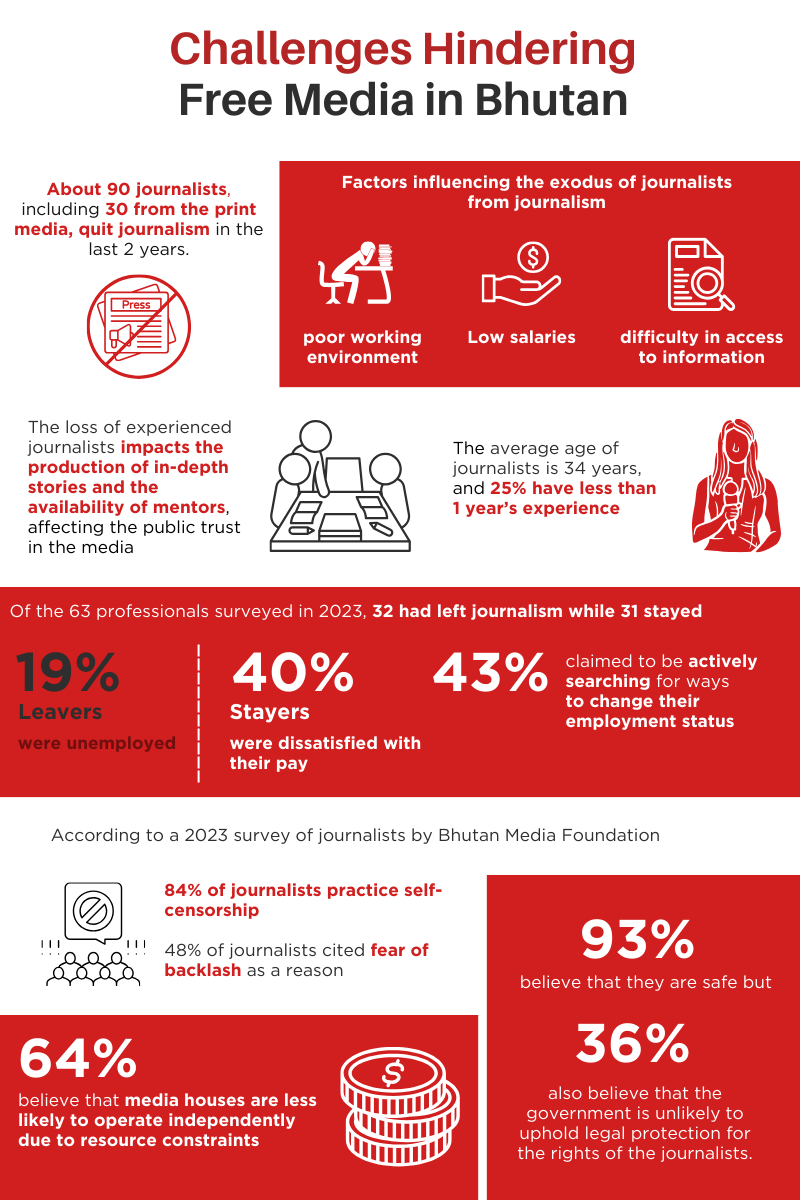

Low salaries, a poor working environment and difficulty in access to information are seen as factors influencing the exodus of journalists from journalism. Bhutan’s top daily, the state-owned Kuensel, lost two senior editors between October 2023 and February 2024. According to Kuensel, the number of working journalists fell by 37 per cent from 2021 to 2023, with only four out of 15 vacancies filled over the past two years. About 90 journalists, including 30 from the print media, quit journalism in the last two years. The Bhutan Broadcasting Service (BBS) alone lost 60 employees, with news reporters, producers, camerapersons, and editors leaving en masse.

Bhutanese journalism is characterised by relatively younger journalists with mixed experience and greater gender parity. The average age of journalists is 34 years, and 25 per cent have less than one year’s experience. The loss of experienced journalists impacts the production of in-depth stories and availability of mentors for young journalists, with a detrimental effect on public trust in the media.

Jumping ship

To understand the issues driving journalists out of the profession, the Centre for Bhutan & GNH Studies (CBS) in 2023 conducted a survey of professionals who had worked as journalists in the past five years. Of the 63 professionals surveyed, 32 had left the profession (“leavers”), while 31 stayed in the media (“stayers”). There was no difference between stayers and leavers in terms of gender, age (mostly 31-40 years old), marital status (mostly married), number of children and years of journalism experience. Most of them self-reported as being passionate about journalism.

Of those who left the profession, 66 per cent left in the past two years, and 44 per cent left the country (mostly for Australia). The rest remained in Bhutan but were no longer working as journalists. Of the leavers, 19 per cent are now unemployed, while the other 81 per cent have moved on to new jobs, including teaching in Bhutan and elder care in Australia. When asked about reasons for leaving the profession, low salary and lack of professional development emerged as the most common factors.

Of the stayers, 40 per cent expressed dissatisfaction with their pay, and 43 per cent claimed to be actively searching for ways to change their employment status. Lack of access to information was a common concern, with nearly two-thirds of the 63 respondents identifying this as the main challenge for journalists working in Bhutan.

Past glory

It was not always like this, however. The advent of democracy in 2008 heralded a period of rapid growth for privately-owned media, which thrived under constitutional guarantees of freedom of expression, press freedom and the right to information. A foundation was laid for a robust media environment which saw the launch of ten newspapers, including four Dzongkha language publications, during its golden phase from 2006 to 2010.

However, this period of prosperity was short-lived, as economic challenges began to erode the media’s newfound vibrancy. The first democratically elected government resorted to austerity measures as the country faced a major economic crisis in 2010. Consequently, five newspapers, three radio stations, and two magazines closed down, leaving a smaller, albeit resilient, media landscape.

The Bhutan Media Foundation (BMF) conducted a nation-wide survey in September 2023 to generate data on the current state of journalism in Bhutan with a focus on three basic issues – safety and security of journalists, rights of journalists, and access to information. Thirteen media houses and freelancers served as clusters that included seven newspapers, one TV station, three radio stations, two OTT platforms, and one separate category – freelancers. Ninety-eight of the total number of 136 journalists in Bhutan responded to the survey.

The BMF survey highlighted a decline in newspaper circulation since 2013. Despite this, newspapers remain the primary medium for journalists in Bhutan employing 41 per cent of the total media workforce, followed by television with 27 per cent, radio and online platforms (13 per cent each), and OTT, the youngest medium, holding a 6 per cent share. However, the small market necessitates government subsidies for private media survival, creating dependencies that impact editorial independence. Presently, Bhutan’s population of 750,000 is served by seven newspapers, one government-owned TV station, four radio stations, and two OTT platforms.

The BMF study also found that media houses are not able to provide adequate compensation to their journalists who work for longer hours. More experienced journalists caught in this situation continue to look for greener pastures, contributing to a higher attrition rate. As a fallout of this process, media houses end up exhausting their professional development funds just to provide basic journalism training to larger numbers of new entrants. Consequently, higher level training takes a backseat. Financial constraints have also prevented media houses from undertaking technological upgrades.

Media Rights Violations

Killings

Arrests

The loss of experienced journalists impacts the production of in-depth stories and availability of mentors for young journalists, with a detrimental effect on public trust in the media.

A man sits on a roadside as he ask for alms near a market in Bhutan’s capital Thimphu on January 10, 2024. Many journalists have recorded practicing self-censorship, with a majority identifying a fear of backlash and ‘small society syndrome’ as ke reasons behind the practice. Credit: Money Sharma / AFP

Small society syndrome

Bhutan’s press freedom faced a setback in 2023, as reflected in the World Press Freedom Index by the Reporters Without Borders (RSF). The country’s ranking plummeted from 33rd to 90th place. Experts attribute this decline to the information blockade, media hollowing, sustainability challenges and self-censorship.

Self-censorship results in reporters not covering sensitive issues. According to the BMF survey, a very high number – 84 per cent – of journalists practice self-censorship. Of these, about 59 per cent practice self-censorship sometimes, while 25 per cent practice it often. Interestingly, male journalists are one and a half times more likely to practice self-censorship as compared to their female counterparts. Mid-level journalists tend to practice self-censorship less frequently than entry-level and senior journalists.

Fifty-three per cent of journalists stated that “small society syndrome,” a term used to describe a well-knit society where everybody knows everyone else, and the fear of backlash are the two major reasons for self-censorship. The fear of backlash is found to be the second most important reason for self-censorship, with 48 per cent of journalists citing it as a reason. Other reasons such as external regulations and fear of losing a job, were almost equally rated.

The survey also reveals that the issue of safety and security of journalists is associated with the kind of stories they cover. Most journalists in Bhutan focus on non-controversial stories; consequently, they do not face threats to personal safety and security. However, investigative stories or opinion pieces may be subjected to online harassment owing to social media’s development in Bhutan.

BMF’s media survey also found that those who cover investigative/analytical stories tend to have psychological fears and face safety and security challenges. The survey found that only 10 per cent of the journalists who responded felt comfortable pursuing investigative stories. “TV journalists reported that social media had become very critical and has trolled/abused them,” the report stated.

Fifty-three per cent of journalists stated that “small society syndrome,” a term used to describe a well-knit society where everybody knows everyone else, and the fear of backlash are the two major reasons for self-censorship.

Information blockade

Bhutan lacks a law that ensures the media’s right to access information. The Bhutan InfoComm and Media Authority (BICMA) regulates the media sector in Bhutan through the Information, Communication and Media Act of Bhutan 2018. This Act provides procedures and criteria for accrediting media in Bhutan and outlines a detailed code of conduct for journalists.

The enactment of the Right to Information Act is considered vital for vibrant journalism in Bhutan. Successive governments have shelved the right to information legislation, leaving it in cold storage. With no systematic or institutional mechanism in place to facilitate access to information, bureaucracies such as the Royal Civil Service Commission (RCSC), Anti-Corruption Commission, Office of the Attorney General, Thimphu Municipality, and even the Parliament have devised their own model codes and rules to restrict the sharing of public information.

Further, the scrapping of the autonomous Media Council with membership of industry representatives to oversee media content and its transfer back to BICMA does not bode well for access to information.

A series of rules and notifications from various agencies have effectively silenced civil servants, with agencies seemingly competing to withhold access to information. The BMF survey noted that 84 per cent of Bhutanese journalists reported various degrees of difficulty in obtaining information from bureaucracies. Additionally, 64 per cent of journalists believe that public officials are unlikely to talk to them, while 82 per cent believe that their stories are subject to censorship. Only 10 per cent of the journalists surveyed feel comfortable pursuing investigative stories.

The BMF’s survey also reveals that two-thirds of Bhutanese journalists report having their requests for information often refused by authorities. Reasons cited for refusal include being “not authorized to share information,” “information under process,” or simply claiming “do not have information,” according to the survey.

The Code of Conduct issued in 2023 by the RCSC restrained civil servants from speaking to the media and mandated disciplinary actions for speaking to the media. Given these restrictions, it is not surprising that the BMF survey found that personal contacts, anonymity, and discretion dominate the system of accessing information, affecting its validity and reliability.

While civil servants are not permitted to talk directly to the media, all offices are mandated to appoint a focal person to facilitate communication between the media and the respective office. However, significant loopholes persist as some offices still lack a designated media focal person, and even where appointments have been made, officials are not always effective in ensuring the free flow of information.

In some offices, the media is required to obtain permission from the head of the agency to engage with their subordinates. Unfortunately, accessing these higher authorities proves challenging, as they are often unavailable or reluctant to grant media interactions with relevant officials. This practice not only impedes the dissemination of information but also creates delays as inquiries must navigate multiple layers within the agency, depriving reporters of firsthand, timely information.

A series of rules and notifications from various agencies have effectively silenced civil servants, with agencies seemingly competing to withhold access to information.

India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi (C) holds hands with Bhutan’s King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck (R) and His Majesty Jigme Singye Wangchuck, the Fourth King of Bhutan, during a ceremony in Thimphu on March 22, 2024. Freedom of information in Bhutan is strained, with the nation’s civil servants restricting from speaking directly to the media. Credit: Upasana Dahal / AFP

Unsustainable industry

The media industry is also confronted with a high turnover of journalists which impacts the quality of news reporting as well as creates sustainability issues. Private media depends on advertising which is 80 per cent generated by the government, which has an inevitable impact on the editorial decision.

The government provides annual subsidies to private media houses. The subsidy is equally divided among all the private media houses irrespective of their market share. This system has not only protected the inefficient media houses, but also prevented greater gains for the more viable ones.

According to BMF’s survey, 64 per cent of the journalists believe that media houses are less likely to operate independently due to resource constraints. The small market, declining readership/viewership and limited private advertisements impose limitations on the capacity of the media houses to generate adequate revenue and achieve financial sustainability. “The financial status of the media houses is unlikely to change over the next three to five years,” it stated.

The government subsidy to the media is an important source of financial resources and keeps them afloat. Only 24 per cent of journalists believe that the government subsidy is not adequate, 31 per cent believe that it is highly adequate, and 45 per cent think it is moderately adequate.

Experts believe that the market can sustain only up to three newspapers in Bhutan. Newspapers are most likely to shift towards online versions with improved and non-shareable features of subscription. The viability of these digital platforms will be a challenge, given the limited revenue available.

Safe haven

Despite being a nascent democracy with limited access to information, Bhutan provides a relatively safe working environment for journalists. There has not been a single incident of killing or physical assault of journalists in the country. Journalists are not subject to persecution and arbitrary detention by the state. Ninety-three per cent of the Bhutanese journalists believe that they are safe as per the BMF survey.

According to the BMF survey, journalists self-censor and avoid controversial stories in order to reduce risk to their personal safety and security. “Higher levels of self-censorship are probably a reason why journalism in Bhutan is a less risky profession compared to other parts of the world. Journalists refrain from publishing stories that are controversial and politically and socially risky,” said the report.

However, verbal intimidation, insult/ abuse/hate speech, online intimidation, and trolling on social media adversely affect the safety perception of journalists in Bhutan. Cases of harassment, physical intimidation, and defamation charges have also been experienced by one in every six or seven journalists in the country. Journalists working on online platforms are more likely to face negative consequences o their work.

Despite being relatively safer for journalism than most of its neighbours, the majority of media organisations in Bhutan do not have a safety policy, as reported by 60 per cent of journalists. Of those who have a safety policy, 59 per cent have a clear procedure to report the cases, and only 31 per cent effectively implement the safety policy. Organisational support to victim journalists is not holistic, and is limited to reporting of cases, legal support and paid leave.

The BMF report also stated that the legal, political and economic environment is not conducive to the protection of the rights of journalists. The composite indices show that online journalists, freelancers, and print media are the most vulnerable groups. Sixty-one per cent of journalists believe that the constitution and other rules and regulations protect the rights of journalists in Bhutan. Thirty-six per cent of journalists believe that the government is unlikely to uphold legal protection for the rights of the journalists.

Bhutanese journalists face a moderately risky environment in terms of protection of their rights. Though gender-based differences are not observed, online and freelance journalists face the greatest risk to their rights.

The small market, declining readership/viewership and limited private advertisements impose limitations on the capacity of the media houses to generate adequate revenue and achieve financial sustainability.

“Higher levels of self-censorship are probably a reason why journalism in Bhutan is a less risky profession compared to other parts of the world. Journalists refrain from publishing stories that are controversial and politically and socially risky.”

Students at attend a Journalists Association of Bhutan workshop on the importance of fact-checking in combatting misinformation. A lack of economic resources has restricted outlet’s abilities to retain staff, improve equipment, or provide improving conditions and pay, requiring intervention from NGOs and international actors to secure he future of the industry. Credit: JAB

Women friendly space

Female journalists in Bhutan have a relatively friendly working environment, and they are confident enough to take on field-based work as they do not face significant sexual harassment or sexual violence. They also stated that female journalists are provided flexible working hours and can work from home.

The BMF survey reveals that the choice of stories reflects a common pattern between male and female journalists in Bhutan, news items are most preferred, investigative stories are least preferred and the rest are almost equally preferred. A larger percentage of female journalists opt to cover news items (62 per cent) as compared to male journalists (51 per cent). Only two per cent of female journalists pick up investigative stories as compared to four per cent of male journalists.

Campaign promises

Amidst media reports highlighting the challenges that Bhutanese journalists face in accessing information from authorities, the recent assurance of support by the newly elected government and its willingness to engage with the media is seen by many as a beacon of hope for Bhutanese journalism.

The fourth-elected government campaigned on a promise to champion free and independent media, streamline access to information and enhance the media landscape with new initiatives and incentives.

During his first meet-the-press session on February 29, 2024, Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay underscored the pivotal role of the media in upholding democratic principles, emphasising the accountability of the elected government to the people and urged the media not to shy away from critiquing and engaging in debates over government policies.

While challenges persist, Bhutanese journalists view the government’s overtures as a positive step towards fostering a vibrant and independent media landscape. “The prime minister’s commitment has instilled in us a sense of positivity and anticipation for a better future for journalism in the country,” said a senior journalist based in Thimphu. “However, translating rhetoric into tangible reforms will require sustained collaboration between stakeholders and a commitment to institutionalising media freedom,” he added.

Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay underscored the pivotal role of the media in upholding democratic principles, emphasising the accountability of the elected government to the people and urged the media not to shy away from critiquing and engaging in debates over government policies.

JAB President Rinzin Wangchuk (L), former Prime Minister Lotay Tshering, and Bhutan Media Foundation Executive Director Needrup Zangpo post for a photo at the newly-inaugurated Thimphu Press Club on July 15, 2023. Credit: BMF / Facebook

Way forward

To realise the promise of a free and robust media, Bhutan must prioritise legal reform to safeguard journalists’ rights and facilitate information access. Institutionalising media spokespersons and streamlining communication channels will enhance transparency and accountability.

Investments in professional development and technological infrastructure are essential to bolster media resilience and innovation. Collaborative efforts between government, media organisations and civil society are crucial to navigating Bhutan’s media landscape towards greater autonomy and effectiveness.

According to BMF, the media in Bhutan will have to shift from quantity to quality, moving towards the role of gatekeepers from its current narrative-driven approach. Media houses and the government will need to encourage innovation and foster flexibility to evolve with changing trends and technology.

It also stated that journalists in Bhutan will need to collaborate with international news agencies or global media houses to add to experience as well as earnings. “This will call for an appropriate supportive regulatory framework.” The report recommends that organisations like BMF and associations like the Journalists’ Association of Bhutan (JAB) establish better linkages with institutions of higher education to support the professional needs of new age media.

The Centre for Bhutan & GNH Studies survey provides some hints as to how journalist retention can be improved and the media industry itself can get a leg up. Fostering professional development seems to be key. This would include not only training and advancement opportunities but also building an enabling environment in which journalists can access the information they need to explore topics in public interest. Such investment will help ensure that the media continues to grow into serving a critical role in strengthening Bhutan’s democracy.