PAKISTAN

Media Under Fire

A supporter of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party blocks Peshawar to Islamabad highway as she protests against the alleged skewing in Pakistan’s national election results, in Peshawar on February 11, 2024. Government instability and restrictions on PTI were a leading cause of unrest across Pakistan, with nation-wide, violent protests seen in the wake of former Prime Minister Imran Khan’s arrest in May 2023. Credit: Abdul Majeed / AFP

A messy political transition in Pakistan that saw three governments and a lengthy six-month constitutional limbo between an outgoing parliament and an incoming one, adversely and substantially affected media freedoms in the period under review.

Journalists and bloggers found themselves an easy punching bag for the security establishment in its confrontation with the party of former prime minister Imran Khan. As evidenced from their policy actions, none of the three governments in the period under review made a departure from recent years of often casual and sometimes wanton repression of freedom of expression in general and intimidation of journalists in particular.

Over 300 journalists and bloggers this year were affected by state coercion and targeted, including dozens of journalists arrested for durations between several hours to four weeks and nearly 60 served legal notices or summons for their journalism work or personal dissent online. At least eight were charged for alleged sedition, terrorism and incitement to violence – all serious charges carrying lengthy sentences and even the death penalty. In a majority of cases, these actions against journalists stemmed from their perceived and actual support for Imran Khan and his party. In this sense, the principal threat actor behind crimes against journalists and free speech practitioners was undoubtedly the state and its functionaries, though some regional sects, non-state actors and gangsters were also involved in some cases.

A repressive measure limiting freedom of expression and access to information this year was largescale restrictions on the internet and social media access. On February 8, 2024, the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) unexpectedly imposed a nationwide suspension of mobile internet services on election day discrediting the democratic exercise and impeding the right of journalists and civilians to free speech. In the same month, rolling restrictions on access to social media platform X were imposed – a closure that stretched to over four weeks.

In the context of combating high levels of impunity of crimes against journalists and other media practitioners legally and procedurally, Pakistan frittered away the advantage of two legislations on the safety of journalists it had enacted in 2021. Under the federal law on the safety of journalists, the government failed to establish a Safety Commission that could pursue cases of assistance. Under the Sindh provincial law on safety of journalists, while a Safety Commission was formed, it was made effectively dysfunctional by not being allocated a budget, an office, staff and technical assistance.

The silver lining was a growing incidence of courts intervening in favour of journalists to impede government attempts to entangling them in legal proceedings as a tool of deterring dissent. The Supreme Court, and three of four provincial high courts intervened to free arrested journalists or have some of the most serious and frivolous charges against them dropped.

Media at a crossroads

While precise data relating to the media industry’s economic health remains insufficient, issues such as wage cuts, job losses, slow technological growth and dwindling state and corporate advertising budgets continue to haunt journalists and legacy media houses across Pakistan.

The media landscape remains riddled with uncertainty, with journalists facing layoffs and prospects of future employment elusive. A ‘Decent Work Survey’ conducted by the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) in 2023 in Sindh revealed the extent of adverse labour conditions for media workers. Only 39 per cent were employed and just 28 per cent had fixed term contracts. About 59 per cent said that their contract was not renewed annually and just 29 per cent got opportunities for career advancement. Around 60 per cent of journalists interviewed earned less than PKR 35,000 (USD125) per month. A large number complained of wage payment arrears and delays, being overworked and under-compensated with few or no standard benefits.

Attributed in part to mounting advertising arrears, Pakistan’s conventional media sector is struggling. Despite repeated reassurances regarding settling overdue payments and an increase in advertising rates, the leverage enjoyed by government agencies has impeded efficient functioning of media outlets. In August 2023, the government announced a 35 per cent increase in government advertisement rates for the print media, accepting a demand from the All Pakistan Newspapers Society, the representative body for newspaper owners. In September, the authorities informed the Senate that they had released PKR. 9.6 billion (about USD 3.5 million) in advertisement arrears to various media houses in the preceding 18 months.

Despite challenges, there have been some efforts aimed at facilitating media workers. In June 2023, the federal government earmarked PKR 1 billion to insure journalists against health emergencies. Under this scheme, journalists would be able to access healthcare for up to PKR 1.5 million (over USD 5,000) per person at over 1,200 health facilities. In October 2023, the provincial Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government promised to amend endowment rules and increase financial assistance for the province’s media workers facing financial emergencies or those rendered jobless.

Media Rights Violations

Killings

Arrests

The principal threat actor behind crimes against journalists and free speech practitioners was undoubtedly the state and its functionaries, though some regional sects, non-state actors and gangsters were also involved in some cases.

Paramilitary soldiers cordon off an area of the Islamabad High Court during the hearing of former Prime Minister Imran Khan on May 12, 2023. Journalists and bloggers faced arrests, assaults, and legal cases, as media personnel seen to align with Khan faced the judgement of authorities. Credit: Aamir Qureshi / AFP

Wrath of the state

In the period under review, four journalists were killed, two in Punjab (Imtiaz Baig of Samaa TV, Sagheer Ahmad Laar of Daily Khabrain) and two in Sindh (Ghulam Asghar Khand of Sobh newspaper and Jan Muhammad Mahar of Kawish TV). The highest number of violations was in the category of arrest or jailing. Dozens of journalists were arrested and around 250 faced intimidation related to their alleged support of the party of Imran Khan or for their coverage of the protests by his party supporters ensuing from the arrest of the former prime minister on May 9. Apart from these actions, at least eight other journalists were attacked non-fatally in different parts of the country. At least three journalists faced distinct significant threats of death, violence, home invasion or potential demolition of their home from various threat actors for their journalism work. There were also two instances of media houses – both government-owned – being attacked by supporters of former prime minster Imran Khan.

At least 59 journalists and bloggers were charged with sedition, terrorism, incitement to violence, defamation or contempt. Of these, 47 journalists were served legal summons to respond to allegations of targeted defamation and incitement against judges of the superior judiciary. The summons came after the government constituted an investigation team to ascertain critics of the judiciary.

Additionally, at least eight other journalists were attacked in different parts of the country. At least three journalists faced significant threats of death, violence, home invasion or potential demolition of their houses from various actors for their journalism work. There were also two instances of media houses – both government-owned – being attacked by supporters of former prime minster Imran Khan.

Restive provinces

Legal reforms aimed at integrating Pakistan’s tribal areas with the mainstream notwithstanding, anticipated relief for the region’s intimidated media and journalists remains elusive with cases of threats to free speech reported. At least two journalists were threatened by the Taliban and one abducted and tortured before being released. In May 2023, journalist Shams Mohmand raised the alarm regarding concerns for safety of journalists following the assumption of power by the Taliban in neighbouring Afghanistan. Another journalist, Miraj Khalid Wazir, reported being blackmailed by a local jirga – illegal self-styled court – to pay a fine or face demolition of his property for reporting about its activities.

The report ‘Saving Journalism in Pakistan’s Tribal Districts’, by Freedom Network, found unsatisfactory mental health resources available to tribal journalists. With only a single dedicated trauma centre in Peshawar, the region’s media practitioners were forced to leave their work-induced psychological concerns unattended.

Civil strife in Southern Balochistan and limited digital connectivity added to the woes of the province’s journalists already threatened by an unsafe media environment. Trauma counselling has been provided to over 200 Baloch journalists working in conflict zones by Individualland, a local NGO. Also documented was an advocacy campaign by the Balochistan Union of Journalists demanding reduced workloads, insurance schemes and increased remuneration for reporters working in the region’s conflict zones.

Sindh province has been ranked among the most dangerous regions to practice journalism in Pakistan, with at least 56 violations recorded between 2021 and 2023, coming second only to Islamabad, according to the Freedom Network. At least two journalists were killed, one harmed in an armed attack and two threatened with cases for their critical reporting.

Sindh province has been ranked among the most dangerous regions to practice journalism in Pakistan, with at least 56 violations recorded between 2021 and 2023, coming second only to Islamabad

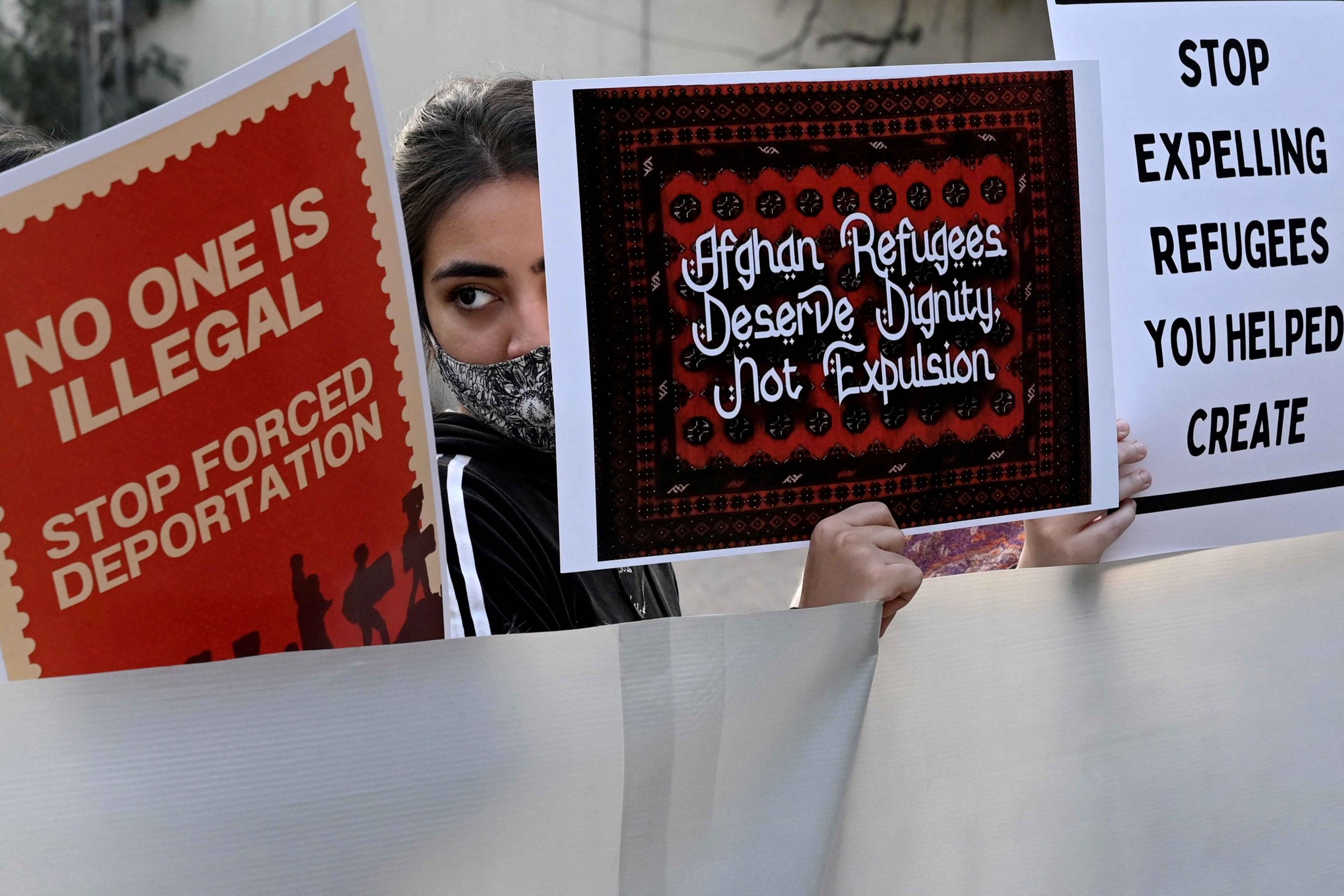

People protest against the deportation of Afghan refugees from Pakistan at a rally by the Women’s Movement ‘Aurat March’, in Lahore on November 18, 2023. At least 200 journalists fled to Pakistan, with many stuck for months awaiting visas and transit approvals to third countries. Credit: Arif Ali / AFP

Exhausted in exile

In October 2023, Pakistan’s government unilaterally demanded that Afghan refugees return to Afghanistan, setting a deadline of one month before authorities began forced deportations. Amongst the refugees were 200 journalists who had fled to Pakistan to escape stifling restrictions on free speech in Afghanistan. In June 2023, IFJ urged state-sponsored humanitarian assistance for Afghan journalists in Pakistan, a support they urgently required to continue as working professionals.

The IFJ initiated a support program for displaced Afghan journalists – both male and female – in collaboration with UNESCO and the PFUJ to provide accommodation in two safe houses in Islamabad, in July 2023. In addition, short-term financial assistance, food, medical, legal/immigration advice, and psychological support facilities were provided.

Freedom network in partnership with RSF, launched the ‘Advocacy Hub for Afghan Journalists’ project in December 2023. Under the project, over 100 exiled Afghan journalists will be provided with financial and legal assistance to support their sustenance and freedom to report. This will provide some relief to Afghan women journalists in particular, struggling with visa issues, lack of employment and out-of-school children.

Gender equality still a dream

In the period under review, the safety of women journalists in Pakistan’s online and offline spaces remained a persistent challenge. They continued to face gender-based discrimination, journalism work-related intimidation and under-representation in the industry.

In 2021, a safety inquiry conducted by UNESCO-affiliate International Centre for Journalists among women journalists across 215 countries found every three in four reporting online abuse stemming from fulfilment of their work commitments. The trend observed in Pakistan mirrors these results. In February 2023, news show host Gharida Farooqui reported being threatened with sexual assault and murder by anonymous social media users. Independent journalist Laiba Zainab communicated instances of cyber harassment in October 2023, wherein trolls demanding she censor her political views online. In February 2024, supporters of current ruling party directed online abuse towards anchorperson Meher Bokhari for her alleged tilt towards an opposing political faction.

Subjected to illegal detention and harassment by law enforcement authorities in December 2023, journalists Somaiyah Hafeez and Fatima Razzak found it difficult to cover protests led by Baloch women activists in Islamabad.

There was a small judicial reprieve when in December 2023, a TV channel was directed by the Islamabad High Court to issue a formal apology and submit PKR 50,000 (USD180) as compensation to journalist Asma Sherazi for airing baseless and defamatory content against her.

A surge of independent women journalists and multimedia content creators was recorded in Balochistan, a region marked by destabilisation and limited digital connectivity. Women journalists have been starting channels on YouTube, all the while navigating through an environment generally adverse to media attention.

In December 2023, IFJ-supported Women’s Media Forum Pakistan (WMFP), established in early 2023, launched a rolling campaign to advocate gender inclusivity in the media industry. Titled ‘Pakistan’s Media Needs Women’, the campaign supports conversations relating to labour laws, gender sensitive newsrooms and the acceptance of women journalists in senior leadership roles. In January 2024, media stakeholders, including IFJ and the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ), reiterated their support to WMFP’s campaign, pledging to proactively tackle underlying issues such as inclusivity, equal representation, and fair wages. The Forum used its dedicated WhatsApp group to host frequent online meetings, along with Twitter spaces and webinars and continued to sensitise various stakeholders and foster discourse on inclusive media spaces.

Likewise, a gender audit of Islamabad-based news media organisations by Freedom Network and the Women Journalists Association of Pakistan revealed concerning statistics. Among 15 Islamabad-based media news outlets, the average representation of women staffers did not exceed 11 per cent while at least nine outlets afforded no senior management position to a woman journalist. It urged media outlets to adopt a consolidated gender strategy, including a commitment to complying with gender-based laws, improving their gender ratio among staff employed and to follow fair wage guidelines put forth by IFJ-affiliate PFUJ.

In the period in review, the National Press Club announced a ‘Women Journalists Caucus’ and set up a working committee to strategise the initiative aimed at improving the professional competence of women journalists. In June 2023, the IFJ conducted a series of workshops to train women journalists to conduct a mapping of pre-selected press clubs, unions and media outlets across the country. The resulting report, ‘Mapping Women and Gender in Pakistan’s Media’ revealed low numbers of women working in media, especially in remote areas. Despite women comprising between 5-30 per cent of media workforces in mapped areas, women in decision-making roles was often less than 10 per cent or none at all. Media house unions are either non-existent or ineffective in addressing workplace issues, particularly for women journalists. Despite a massive growth in press club memberships over the past two decades, this has not translated to greater entry for women journalists.

Drawing heavy criticism from home and abroad, the government replaced the Digital Security Act (DSA) with another law, the Cyber Security Act (CSA).

Drawing heavy criticism from home and abroad, the government replaced the Digital Security Act (DSA) with another law, the Cyber Security Act (CSA).

Pakistan’s former prime minister Imran Khan’s supporter listens to a virtual election campaign on a phone at the offices of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party in Islamabad on February 3, 2024. Authorities in Pakistan have been responsible for wide-reaching and prolonged internet censorship and surveillance, impacting free expression and the media. Credit: Aamir Qureshi / AFP

Extremism’s ominous presence

Another year has passed with little relief in constraints to freedom of expression influenced by right-wing extremism in Pakistan. If anything, the state apparatus continues to entertain often unsubstantiated general complaints of alleged blasphemy online, putting citizens and sometimes journalists in potentially serious trouble. An air of palpable self-censorship is practiced by journalists and media outlets on topics concerning law and religion, afraid as they are of attracting blasphemy allegations. This atmosphere of intimidation has eroded the quality and quantity of independent reporting on sensitive issues.

While there has been little action on hate speech against journalists, civil society and activists, the government is spending considerable effort in controlling social media expression. Sometimes the scale of official response to perceived ‘extremism’ online, particularly free speech, can be staggering. In July 2023, the Federal Investigation Agency acknowledged monitoring over 400,000 social media accounts accused of allegedly uploading blasphemous content on social media. In March 2024, a student was sentenced to death and a minor handed life imprisonment for allegedly sending blasphemous pictures and videos through WhatsApp messages.

Deterrents online

In the period under review, Pakistan’s government imposed unprecedented restrictions on free speech and access to online spaces. These measures, in contravention of rights ensured under the constitution, raise serious concerns regarding safety of free speech practitioners, including journalists, and also about data privacy.

In January 2023, internet regulator PTA admitted it had made unavailable more than one million websites for containing allegedly ‘unlawful content.’ In May 2023, the government enforced a four-day internet blackout in several regions to suppress violent protests following the arrest of prime minister Imran Khan. In July 2023, Pakistan was ranked third in the world by VPN services provider Surfshark for imposition of restrictions on the internet.

In January 2024, the Telecom Operators Association wrote to the PTA, seeking clarity on recurring internet restrictions impacting digital businesses and the free exchange of information. On election day, February 8, 2024, PTA unexpectedly imposed a nationwide suspension of mobile internet services, contrary to prior promises made before a court. In the same month the authorities shut down access to social media platform X (formerly Twitter). Despite directions issued by the Sindh High Court to lift restrictions, access to the platform remained interrupted for weeks. According to internet rights group Bytes for All, separate incidents of internet shutdowns in Pakistan exceeded 15 in number during 2023. Dozens of Pakistani media support groups, digital rights organisations and media rights activists issued a joint statement criticising continued disruption of media platforms across the country.

In July 2023, TikTok said it had taken down over 11 million videos originating from Pakistan, as a response to government requests and incompatibility with its community guidelines.

Digital journalism

The 2023 Annual State of Digital Journalism report, produced by the Institute for Research, Advocacy and Development (IRADA), said that the independence of digital journalism in Pakistan is challenged by recurrent governmental overreach, internet shutdowns, financial viability and freedom to express. It said that despite challenges, Pakistan’s digital media players were adopting indigenous fact-checking mechanisms, exploring additional revenue streams and becoming members of unions to further their interests in a consolidated manner.

Pakistan’s digital media landscape also experienced some positive developments in the period under review. In January 2024, the government announced it would launch 5G connectivity and its affiliated services in the same year. In March 2024, Pakistan’s growing IT prowess was at display at LEAP 2024 in Saudi Arabia, where the country’s contingent of 74 companies was among the largest.

An audience survey of religious minority communities by IRADA, released in late 2023, revealed that the internet is the most used medium amongst religious minorities with 76 per cent respondents using it several times a day. Television is the second most popular choice with at least 48 per cent respondents viewing it once a day. One-third of respondents said media does not adequately represent their community interests and 63 per cent said that the media did provide information that is relevant to them. ‘News and current affairs’ was the most popular media subject consumed by religious minorities (90 per cent), followed by news about their community (53 per cent).

In January 2024, the government constituted a joint investigation team to identify those behind an alleged organised online campaign targeting members of Pakistan’s judiciary. Following its constitution, the FIA summoned 47 journalists and YouTubers to explain publication of their views on digital platforms ‘targeting’ the judiciary.

Drawing heavy criticism from home and abroad, the government replaced the Digital Security Act (DSA) with another law, the Cyber Security Act (CSA).

Members of the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ) hold a protest commemorating World Press Freedom Day outside the Karachi Press Club on May 3, 2023. Four journalists were killed over the past 12 months, with dozens more detained , assaulted, or harassed for their work. Credit: PFUJ

Journalists targeted

Pakistan’s media safety landscape, in the period under review, was blotted by a series of challenges, including impunity for crimes against journalists, targeted killings, government heavy-handedness, legal cases, unlawful detentions, and online attacks.

Four journalists paid the ultimate price for their work. In August 2023, journalist Jan Mohammad Mahar was killed after unknown assailants shot at his vehicle minutes after he left his workplace in Sukkur. His murder sent a wave of anger amongst journalists and civil society members. Despite three suspects in custody, authorities have been unable to provide a conclusive explanation for this brutal murder. Other journalists who paid the ultimate price for their public interest journalism were Imtiaz Baig who was clubbed to death in Jhelum in May 2023 and Ghulam Asghar Khand and Jan Mohammad Mahar who were assassinated in armed attacks in Khairpur and Sukkur in August 2023. Sagheer Ahmad Laar was murdered in an armed attack in Khanpur on March 14, 2024.

In May 2023, anchor Imran Riaz Khan went untraceable following his arrest from Sialkot. While the Lahore High Court issued consecutive directions for his recovery, law enforcement and armed forces denied having him in custody. In September 2023, Imran returned home after four months in frail health after the courts threatened action. In February 2024, he faced yet another arrest, this time on allegations of corruption. After his legal team posted bail in this case, he was placed under judicial remand in another terrorism-related case.

On February 6, 2024, YouTuber Asad Ali Toor was arrested by the Federal Investigation Agency. This action followed a gruelling interrogation on accusations of maligning the judiciary on social media. In March 2024, the Islamabad High Court ordered him freed on bail, responding to the Supreme Court chief justice’s rebuke of the government’s harassment of journalists critical of judicial rulings. Asad was granted bail on March 16, 2024.

On May 9, 2023, following the arrest of former prime minister Imran Khan on charges of corruption, violent protests erupted across Pakistan, primarily led by supporters of his party. These protests resulted in widespread damage to both public and private property. In response, the government imposed cellular and broadband shutdowns in several regions for four days, detaining thousands of political leaders and activists. These actions strikingly did not distinguish between its recipients as dozens of journalists were arrested, attacked and manhandled. At least three journalists, including Imran Riaz Khan and Sami Abraham, went missing, with others – notably Moeed Pirzada and Sabir Shakir – fleeing the country to evade arrest. Media bodies, including their international partners, strongly criticised this high-handedness towards journalists.

Impunity for crimes against journalists continued, a notable unsolved case being that of Pakistani journalist Arshad Sharif who was shot dead in October 2022 by police personnel as he drove to Nairobi in Kenya, sparking widespread public outcry. Arshad’s family rejected a government-appointed investigation committee. The Supreme Court intervened and appointed a specialised investigation team. While the team released two progress reports, the latest in March 2023, both failed to identify a motive or the perpetrators of the assassination. Arshad’s wife pursues cases in both Kenya and Pakistan seeking justice for her husband. The IFJ noted in October 2023, “The fact that proceedings have failed to progress… is a gross miscarriage of justice.”

Legal squeeze

During the period under review, there was a notable escalation in efforts by the previous parliament (whose tenure ended in August 2023) to restrict free speech and intensify digital surveillance. This trend worried journalists, who viewed hastily approved legislations as an indication of collusion between the government and the security establishment to suppress dissent, harass critical journalists, and manipulate the flow of information in its favour.

In May 2023, the parliament passed the Contempt of Parliament Bill, 2023, allowing lawmakers to hold civilians, including journalists and critics, under contempt, imposing penalties of six-month jail or a fine of PKR1 million (USD3,500) for those found guilty. The Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ) demanded that, “The government should ensure that [the bill] is not used against journalists.”

In July 2023, the parliament passed amendments to the broadcast media law Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (PEMRA) Act, 2007, after it was earlier withdrawn by the government following criticism by journalists and media bodies. Key changes to the act included enhanced wage protection for media workers (Section 20-A), expansion of definitions relating to misinformation and disinformation, a ten-fold increase in punishment from PKR1 million (USD3,500) for outlets ‘deliberately’ broadcasting false news and inclusion of PFUJ and Pakistan Broadcasters Association as non-voting members of the PEMRA Authority. PFUJ welcomed the wage protection efforts of the bill.

There was an attempt at increased digital patrolling through two controversial pieces of legislation: the E-Safety Bill and the Personal Data Protection Bill passed in July 2023. Digital rights activists decried these as another attempt by the state to heighten its self-assumed surveillance mandate.

In August 2023, the Senate passed the Official Secrets (Amendment) Act, 2023, after an uproar in parliament forced the government to withdraw a controversial clause which would have allowed intelligence agencies warrantless search and seizures, including those of journalists.

Drawing heavy criticism from home and abroad, the government replaced the Digital Security Act (DSA) with another law, the Cyber Security Act (CSA).

Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party activists and supporters of former Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan clash with police outside the police headquarters where Khan is kept in custody in Islamabad on May 10, 2023, a day after he was arrested. Violent protests following Khan’s arrest resulted in the targeting of journalists and internet personalities, many of which were seen to hold pro-Khan views. Credit: Farooq Naeem / AFP

Spunky local media

Independent digital media outlets in Pakistan face their share of challenges, grappling with financial instability and constraints for expansion. But in recent years, a vibrant league of independent digital media start-ups has been shaking up Pakistan’s prosaic media landscape. Their emphasis on public interest and community reporting has appealed to consumers, with their viewership witnessing an encouraging growth. Viewers are resonating with the appealing production overlay of content published by these outlets. The gradual consolidation of such outlets, for instance those represented by the 26-member Digital Media Alliance of Pakistan (DigiMAP), is enabling relative growth in business and sway within the media industry’s umbrella and posing a healthy challenge for Pakistan’s legacy media.

In 2023, a survey conducted by International Media Support of DigiMAP members that had received trainings on public interest journalism from various capacity building organisations, showed 88 per cent experienced positive outcomes. These trainings allowed the platforms to refine their trade and amplify exposure for Pakistan’s side-lined and under-reported communities. In terms of impact, renowned media outlets such as BBC and Dawn picked up a story by one of the platforms shining a light on the sporting achievements of young Ms Tulsi Meghwar, a member of Sindh’s marginalised Dalit community.

The Search for Common Ground completed an initiative in 2023 aimed at the capacity building of women and youth-led media in under-served regions of Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. The project conducted training sessions and mentored over 60 journalists in conflict-sensitive reporting and building professional networks. Consequently, these journalists produced over 100 small media projects.

In October 2023, Daaman TV, an independent news platform dedicated to providing coverage on human rights and climate issues to residents of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa was selected as one of twelve global outlets for International Press Institute’s prestigious Local News Accelerator programme.

Poor international compliance

Actions contrary to international obligations remained a hallmark in the period under review. In May 2023, IFJ denounced high-handedness by law enforcement authorities towards journalists covering protests following former prime minister Imran Khan’s arrest in Islamabad. The same month, the withdrawal of the Contempt of Parliament Bill was urged, with the fear that it would be used to restrict free speech and critical reporting contrary to international standards of media independence.

The unprecedented promulgation of two landmark pieces of legislation in 2021 – the Sindh Protection of Journalists and Other Media Practitioners and the Protection of Journalists and Media Professionals Act – was aimed at safeguarding media practitioners in Pakistan. The functionality of the Sindh Commission for Protection of Journalists and Other Media Practitioners remained paralysed due to inadequate funding and the absence of dedicated office space and staff. This has increased uncertainty in Pakistan’s ability to comply with objectives outlined under SDG’s target 16.10.

In November 2023, the European External Action Service released its Fourth GSP Report, intended to analyse implementation of 27 international conventions in recipient states, including Pakistan on freedom of expression. Although the report appreciated Pakistan’s legislative progress despite it being a dualist state, it questioned the prevalence of impunity against restrictions on free speech and forced disappearances of civilians, including journalists. The report labelled these hindrances as violations of international commitments, counterproductive to Pakistan’s concessions under the EU’s GSP-Plus trade mechanism.

Disarming disinformation

In the period under review, Pakistan faced the spread of disinformation afflicting its media environment. Journalists and civil society struggled to stem the tide, exacerbated by polarised political campaigns during national elections. A Freedom Network study in partnership with the Coalition Against Disinformation released in early 2024 showed how university students believed social media to be the most popular carrier of fake news, with the majority agreeing that exposure to increased online disinformation posed a threat to Pakistan’s democratic structure and processes.

However, the growing realisation of disinformation’s adverse effects on Pakistan’s socio-political milieu generated some hopeful prospects, with independent organisations introducing innovative fact-checking mechanisms for media stakeholders and social media end-users. In January 2024, the Centre for Excellence in Journalism launched iVerify, a non-partisan online tool to support independent exchange of information. Short-video platform TikTok announced its policy to identify and remove disinformation on its platform during Pakistan elections. In February 2024, Media Matters for Democracy, an NGO, introduced Factor, a collaborative tool for newsrooms to counter disinformation. These indigenous digital resources were aimed at helping journalists and media practitioners to understand and identify disinformation better, thereby deterring sensationalism and biased opinion.

In terms of regulation and action against disinformation, state authorities demonstrated a tilt towards censoring critical voices and overreaching their mandate to protect the freedom to publish on digital platforms.

For instance, the National Assembly, in August 2023, passed an amendment to the broadcast law PEMRA expanding the definitions and scope of disinformation and misinformation. Media representatives called the move an attempt to increase overreach and hound critics. In February 2024, the Sindh High Court accepted a plea submitted by some YouTubers and directed the telecom regulator to ensure filtration of “objectionable and obscene” content from the social media platform, without clarification on what could legally be categorised as ‘objectionable’ content.

Drawing heavy criticism from home and abroad, the government replaced the Digital Security Act (DSA) with another law, the Cyber Security Act (CSA).

Drawing heavy criticism from home and abroad, the government replaced the Digital Security Act (DSA) with another law, the Cyber Security Act (CSA).

IFJ Pakistan Coordinator Ghulam Mustafa (L) and Women’s Media Forum Pakistan (WMFP) Islamabad Coordinator Rashia Shoaib (R) meet with Nayer Ali (C), the newly elected secretary of the National Press Club in Islamabad on March 11, the first woman elected to that position. Her election came following a groundbreaking WMFP campaign, urging unions, press clubs and news outlets to increase the representation of women in the positions of leadership. Credit: IFJ

United for reform

In the period under review, media practitioners and activists undertook various initiatives aimed at bolstering an inclusive and safe environment for journalists and greater solidarity among media workers.

In August 2023, in collaboration with the Digital Media Alliance of Pakistan, the IFJ undertook an initiative on mobilising support for the unionisation of digital journalists. This included development of a working paper on a strategy for the establishment of a labour union for digital journalists. This working paper was used to conduct a series of consultations – supported by awareness campaigns, networking, online engagement, and advocacy – with over 50 digital journalists based in Islamabad, Karachi, Lahore and Quetta. They endorsed the strategy for such a union for the growing ranks of digital journalists who often face challenges of acceptability as equals in other representative platforms. The campaign culminated in an application for registration of a trade union with the National Industrial Relations Commission.

In December 2023, the Women’s Media Forum Pakistan spearheaded a national reform and mobilisation campaign titled “Pakistan’s Media Needs Women” to urge unions, press clubs and media outlets to promote equitable representation for women in the media industry. This is a rolling campaign of awareness raising key issues affecting women and seeking more men to stand up and become ‘agents of change’ in heralding a new era for Pakistan’s media so it can better reflect the gender balance of society.

In August 2023, the Women Journalists Association of Pakistan (WJAP) initiated a campaign aimed at enhancing gender inclusivity in Pakistan’s newsrooms and amplifying awareness on the role of women as communicators of social and political information.

Between August and December 2023, the Digital Media Alliance of Pakistan launched a nationwide advocacy campaign, aiming to highlight the oft-ignored facilitative link between community development and the local digital media. Titled “Local Development is Possible with Local Digital Public Interest Journalism,” the campaign sought to foster local community partnerships with industry stakeholders and fortify Pakistan’s digital media landscape.

In September 2023, Freedom Network, in partnership with the Reporters Without Borders, launched its ‘Advocacy Hub for Afghan Journalists’ endeavour, extending support to journalists seeking refuge in Pakistan amid restrictions posted on freedom of expression by the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. In the same month, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor’s Media Forum unveiled a program to technically equip journalists in Balochistan’s underserved areas.

Way forward

Considering its serious problems of safety of journalists, rights of media workers and the viability of the media industry, especially an expanding digital media without sustainability strategies, stakeholders invested in professional journalism and an enabling environment for freedom of expression, some collaborative efforts are inevitable.

These included continued advocacy for and technical capacity building of public and private mechanisms that aid prevention, protection and legal support for journalists and other media workers targeted, or in distress. Additionally, this also included augmenting support and resources for expanding greater equality and gender equity within media industry, including media houses, unions and press clubs.

All stakeholders worked towards expanding representation, advocacy and protection capacities of the growing ecosystem of digital and freelance journalists who continue to remain under-represented and generally unheard within existing structures. Importantly, advocacy efforts included building legal literacy and legal strategies of journalists and other media practitioners to defend themselves against state targeting and apathy. Strengthening solidarity and professionalism capacities of representative associations of working journalists such as unions and press clubs was also prioritised, to build a unified front against violations of press freedom and journalists’ rights.