INDIA

Unprecedented Challenges

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi waves to supporters as he arrives to attend a Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) campaign meeting ahead of the Telangana state elections at Lal Bahadur Stadium in Hyderabad on November 7, 2023. In India, 2023-2024 saw increasing attacks on journalists, human rights defenders, and political opposition. Credit: Noah Seelam / AFP

The media in India, especially over the past year, has been facing myriad challenges. While one aspect was negotiating for better conditions at the workplace, the bigger challenge was to do with clampdowns by agencies of the state. Alongside, there has been a growing realisation that democracy by itself is not a sufficient condition for guaranteeing media freedoms and that these freedoms have to be consistently defended.

If 2022 and the years before were bad for the Indian media, 2023 has been worse. Apart from the usual hurdles of toxic workplaces, sexual harassment and excessive workload, journalists and media houses had to comply with the narrative set by the government else face various forms of harassment. There was the constant reminder that the media could not be allowed to have a free run. The X (formerly Twitter) handles of many were suspended. Internet shutdowns were imposed during the conflict in the northeastern state of Manipur from May 2023 onward, as well as during the farmers’ protests in February 2024 and often in Jammu and Kashmir.

A private network tracker Top 10VPN estimated that globally, India had the longest internet shutdown in 2023 in terms of user hours. In Manipur alone, the internet shutdown was for almost 5000 hours according to the tracker. In total, the internet was shut down for 7956 hours in India, impacting 59.1 million users.

Precarious work

Despite journalists putting in more work hours, contributing to long form, digital and even ‘piece to camera’, cost-cutting was unrelenting. Journalists continued to be hired on short-term contracts, the extension of which continued to be dependent on subjective appraisals of immediate bosses. The Working Journalists and other Newspaper Employees (Conditions of Service) and Miscellaneous Provisions Act, 1955, is now to be replaced by the Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code, 2020 which removes significant protections for journalists.

The right to unilaterally terminate contracts is vested with the employers and joining unions is strongly discouraged. The tragic death in February 2024 of a resident editor at a leading media group in Mumbai following alleged mental harassment at the hands of his chief editor, became a talking point among journalist organisations about the need for a workplace code of behaviour that discourages power-play and toxic work environments. Many journalist bodies called out the chief editor, who happened to be a woman, by name. While it was accepted that toxic behaviour was not gender specific, the individualisation of the problem exposed its limitations. What did not receive adequate attention was that the pressure to ‘perform’ and grab more ‘eyeballs’ and therefore more revenue, was one exerted from the top, by the corporate owners of the media, dehumanising all positions below, including that of the editor. At a recent prestigious award ceremony for journalists, the chief editor of a paper openly expressed concern about the intimidation of the media by senior members of a right-wing ruling party and the atmosphere that fostered such intimidation.

Fearing reprisal, media houses have become circumspect in terms of the extent to which they critique government policy. This has in turn affected the selection of stories and has led to a kind of self-censorship. Issues that need to be projected in public interest find little space in the mainstream media whereas the independent digital media has been more forthcoming in its diversity of news and views. With digital access being more cost effective for the user, online news portals have been more accessible, with the smartphone serving as a conduit for news. But with legacy media also increasing its footprint online, the competition for advertisement revenue on the digital space has intensified.

Raids and arrests

But the larger attack on livelihoods has been in the form of raids and arrests by central investigating agencies in the offices and homes of owners of news portals. The pattern was clear: portals that had covered events critical of government policies were targeted.

Apart from arrests, other forms of pressure were used. A news magazine which carried a long feature article in February 2024 on the alleged torture and murder of civilians in Jammu was issued a notice by the Information and Broadcasting Ministry under 69 A (security of the state and public order) of the IT Act and the IT Rules, 2021. The story, the video report and the URL were taken down. Nine other URLs sharing the article were also taken down. The editor had to remove the story even though the facts were indisputable, given that the government itself, through its defence minister had assured the aggrieved families of a time-bound investigation and action against the guilty. The news magazine has challenged the notice in court.

The administration in Jammu and Kashmir over the years has stopped issuing advertisements to media which publishes news critical of the government, and the information department has also stopped issuing accreditation cards to journalists of Kashmir, thus making access to official sources extremely challenging.

On the social and economic front, many people’s protests emerged as a reaction to government policies. Farmers, industrial workers and agricultural workers took to non-violent democratic forms of protest. There were laws like the Citizenship Amendment Act that evoked strong emotions across the spectrum as many viewed it as unconstitutional and discriminatory. The media could not ignore these developments as they were important stories. Reports were carried by several media outlets but it was the reportage by independent web portals and YouTubers that came under the government’s scanner.

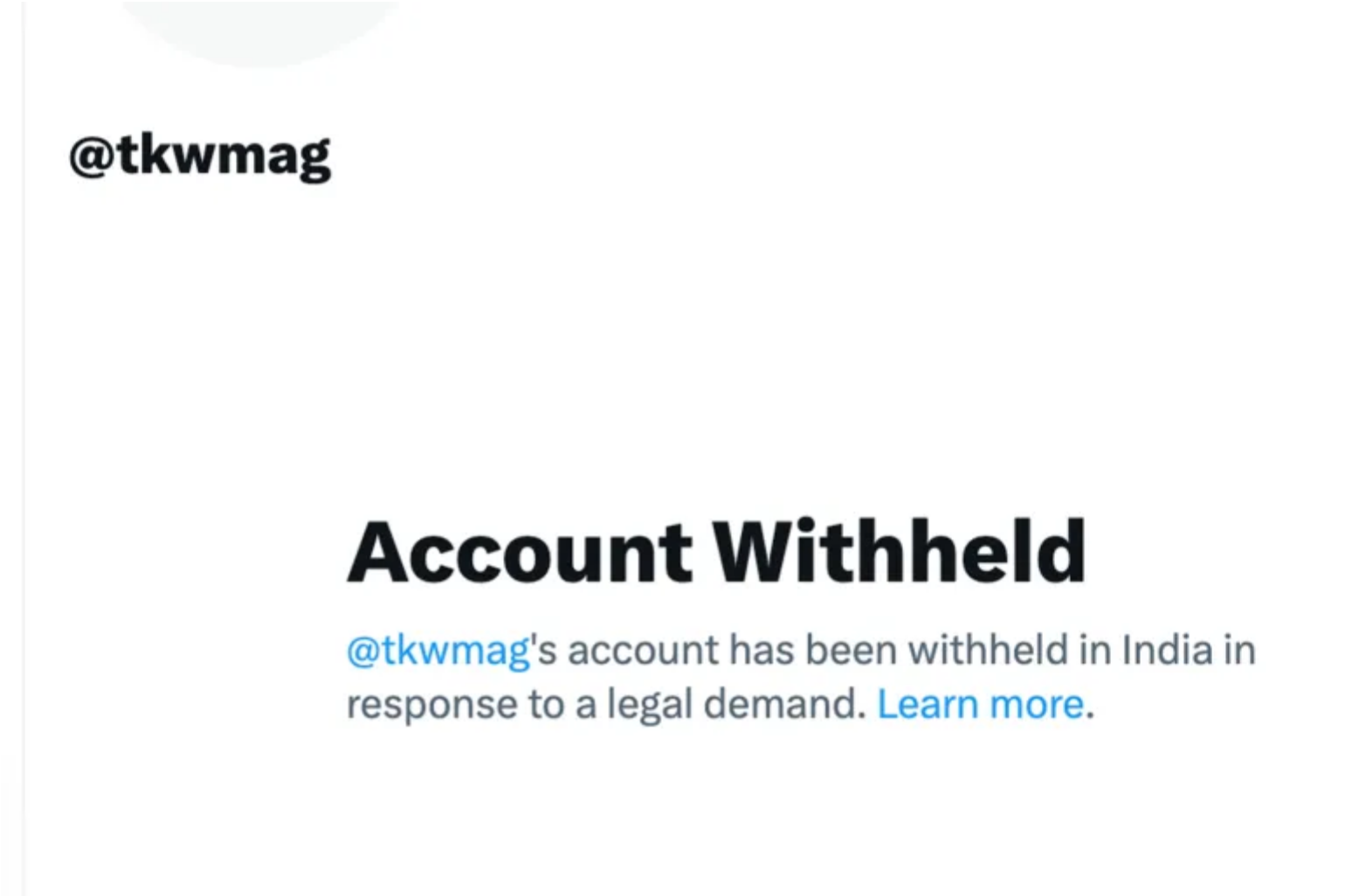

The Ministry of Electronics and IT ordered social media platforms to temporarily block 177 accounts that were linked to farmers’ protests, Elon Musk-led X (formerly Twitter) said it has received executive orders to act against some accounts and posts, “subject to potential penalties including significant fines and imprisonment.”

On February 22, 2024, a post on the X official handle read: “The Indian government has issued executive orders requiring X to act on specific accounts and posts, subject to potential penalties including significant fines and imprisonment. In compliance with the orders, we will withhold these accounts and posts in India alone; however, we disagree with these actions and maintain that freedom of expression should extend to these posts. Consistent with our position, a writ appeal challenging the Indian government’s blocking orders remains pending. We have also provided the impacted users with notice of these actions in accordance with our policies. Due to legal restrictions, we are unable to publish the executive orders, but we believe that making them public is essential for transparency. This lack of disclosure can lead to a lack of accountability and arbitrary decision-making.”

Media Rights Violations

Killings

Arrests

The Ministry of Electronics and IT ordered social media platforms to temporarily block 177 accounts that were linked to farmers’ protests.

People queue at a polling station in local elections in West Bengal on the outskirts of Kolkata on July 8, 2023. With elections held across India through 2023 and 2024, political polarisation , fear of repression, and coverage guided by corporate interest have and will likely contribute to further divisions. Credit: Dibyangshu Sarkar / AFP

Poles apart

The polarisation of the media became sharper in the year under review. This trend began with the change of government at the centre in 2014, with its underpinnings in cultural nationalism. However, the divisions became more pronounced in the subsequent elections as corporate control and cross-media ownership strengthened, and independent voices within the media got stifled or side-lined. The media by and large, took sides, with many in the mainstream aligning with the government at the centre, many out of a shared commitment to the nationalist project, and others due to the perceived threat of persecution or potential loss of advertisement revenue. With more and more media owners preferring compliance, many prominent faces left these mainstream platforms and launched their own news portals on the web.

Financing and funding were a big challenge as their revenue model was contingent on viewership and subscribership and YouTube’s own monopoly on the content and revenue. For the mainstream media, the revenue model was a combination of subscription and advertisements where government advertisements contributed a substantial proportion of the revenue. This became more pronounced during election time.

Due to the polarised atmosphere, a fall-out of right-wing majoritarian politics, journalists covering sensitive subjects were either targeted or told to be careful while covering inter-faith conflicts. In February 2024, violence broke out in Haldwani district, Uttarakhand state after certain structures were demolished. Protests ensued and the administration, led by a right-wing government came down heavily on the protestors. Five people were killed.

A Muslim woman freelancer wrote in her report for the online portal Article 14 how she was advised by her local source to ‘wear shoes’ and run fast if needed. She was also advised to reveal her full name and surname if the police questioned her but to use only her first name among locals, to make her religious identity less obvious. She wrote that another journalist reported that the police were using communal slurs for the minority community. While journalists were mostly prevented from entering the area, some others were given a guided tour by the district administration under the ‘watchful eye of the police’. At least four journalists went public with their ordeal.

‘Advisories’

In the last one year, the government issued significant advisories to the media as well and enacted legislation to regulate digital and broadcast media.

On January 20 2024, the Union Ministry of Information and Broadcasting issued an advisory to the media cautioning it to refrain from publishing/telecasting any content that may be false or manipulated or has the potential to disturb communal harmony or public order in the country. Social media platforms were advised to make ‘reasonable efforts to not host, display or publish information of the nature mentioned above.’ The advisory was issued ahead of the ceremony to consecrate the deity in the Ram temple in Ayodhya in Uttar Pradesh, built on the site of the Babri Masjid demolished in 1992 by members of the Hindu far-right. The high profile religious event scheduled for January 22, 2024 was a matter of much discussion because of the involvement of the Indian prime minister. It was also critiqued by the political class and sections within the media due to the apparent disregard for the secular principles of governance and the alleged politicisation of a religious event. The advisory was effective as a tool of self-censorship, and most TV channels beamed the inauguration live, without any comment, let alone critical reporting.

About a month earlier, on December 26, 2023, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology issued an advisory to all intermediaries to ensure compliance within the existing IT rules. The directive was to address concerns of ‘misinformation powered by AI-Deepfakes’. Intermediaries were told to communicate clearly content that was prohibited under Rule 3(1)(b) of the IT rules.

The digital intermediaries were expected to inform users of penal provisions in the Indian Penal Code and the Information Technology Act. Platforms were required to ‘identify and promptly remove misinformation, false and misleading content and material impersonating others, including deepfakes.’ The advisory quoted the prime minister as expressing concern about the ‘dangers of deep fakes.’

Due to the polarised atmosphere, a fall-out of right-wing majoritarian politics, journalists covering sensitive subjects were either targeted or told to be careful while covering inter-faith conflicts.

The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology issued an advisory to all intermediaries to address concerns of ‘misinformation powered by AI-Deepfakes’.

People stand in front of posters advertising “Namma Wi-fi”, or “Our Wi-fi”, during the launch of free public internet access hotspots in Bengaluru on March 24, 2023. 2023 amendments to the IT Rules hopes to establishing a controversial online Fact Checking Unit, granting authorities ultimate power in deeming online content fake or misleading. Credit: Manjunath Kiran / AFP

Legal ‘nightmare’

The IT Amendment Rules are a nightmare, stated the Internet Freedom Foundation (IFF), an organisation working towards internet freedom and the right to free software. On April 6, 2023, the government notified the amendments to the IT (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics) Rules 2021. According to the IFF, the most alarming feature of the IT Amendment Rules was the provision of a Fact Checking Unit (FCU) aimed at checking fake, false or misleading information pertaining to the central government. The Union Electronics and IT Ministry had notified the FCU on March 20, 2024, as a statutory body under the Press Information Bureau (PIB).

The government had given itself the unilateral powers to identify and decide what was fake, misleading or false. The concept of being a “judge in their own cause” stated the IFF, violated the principles of natural justice.

Under the IT Amendment Rules 2023, intermediaries were required to make reasonable efforts to ensure their users did not post any information related to the business of the Union government which could be false or misleading. The rules do not define what was the “business of the government” or what could be defined as “fake”.

The FCU was given powers to flag what it deemed to be ‘false’ information related to the central government and its agencies on social media sites. Social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and X were legally obliged to take down content identified as misinformation by the FCU, failing which they would be liable to legal action.

The Editors Guild of India and some media organisations had approached the court for a stay, which was denied. However, the Bombay high Court had given a split verdict with one judge pointing out that the setting up the FCU would have a “chilling effect” on the right to free speech and freedom of the press. Many Opposition parties expressed concerns about the FCU. Not only would social media platforms have to take down content flagged by the FCU, internet and telecom service providers too would have to block information. In a significant judgement, on March 21, 2024, the Supreme Court stayed the setting up of the FCU. Both the IT Rules 2021 as well as the amendments to it in 2023 have been challenged in court, one of the main pleas being that the internet was unduly controlled by the executive.

The draft Broadcasting (Services) Regulation Bill, 2023 is another piece of legislation that has elicited concern across broadcasters, journalist bodies and digital news media. The bill that seeks to replace the 30-year-old Cable Television Networks (Regulation) Act, 1995 aims to provide a comprehensive set of norms for all kinds of broadcasting content, from television to streaming platforms. It requires every broadcaster and broadcasting network operator to constitute Content Evaluation Committees (CEC), which would grant certification. The central government may prescribe the members of this committee and also prescribe programs, for which a prior certification from the CEC was not required.

The central government or any agency authorised by it had the absolute right to inspect broadcasting networks and services, with no prior permission or intimation required. Section 31 gives powers to seize and confiscate equipment, if the authorised officer has reason to believe that provisions under the Act, Rules or guidelines were being contravened by the operator.

In streamlining the regulatory framework, the bill extends its purview to Over the Top (OTT) content and digital news. It claims to introduce “contemporary provisions and definition for emerging technologies.” The IFF has warned that under the bill, failure to comply with its provisions may lead to penalties ranging from censorship of content and having to air an apology to the broadcaster, being kept off-air for some hours or days, in addition to a fine. Repeated instances of non-compliance could lead to the broadcaster’s registration being cancelled.

If the bill were to become law, it could alter the media landscape in the country. Apprehensions have been expressed across a wide spectrum, that the proposed bill may affect news and encourage censorship. Over 300 citizens, journalists and civil society organisations wrote to the government demanding that the draft bill should be made available in all languages in order to have meaningful consultations. They highlighted the need for an “open, inclusive, and comprehensive consultation” on the bill due to its far-reaching consequences.

The most alarming feature of the IT Amendment Rules was the provision of a Fact Checking Unit (FCU) aimed at checking fake, false or misleading information pertaining to the central government.

Members of student organisations shout slogans as they hold placards during a protest along a street in New Delhi on October 04, 2023, to condemn the recent arrest of NewsClick founder Prabir Purkayastha and administrative officer Amit Chakraborty on October 3. Over 46 current and former staff members and media personnel were questioned after police initatied action in response to a controversial New York Times report. Credit: Arun Sankar / AFP

Digital doom

Concerns were also expressed on the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 (DPDP). In a letter to the government, the Editors’ Guild of India said that the DPDP Act, if applied indiscriminately to the processing of personal data, would bring journalism to a standstill. It would impact freedom of the press and the dissemination of information not just in reporting in print, TV and the internet but also the issuance of press releases by political parties. The Act is aimed at regulating the collection, use and storage of personal data. The Act before being legislated, had included certain amendments to the Right to Information Act, 2005. One crucial amendment to the RTI Act made through the DPDP Act was the exemption of all personal information from the purview of the RTI Act. Earlier, there were certain exemptions based on which personal information could be given.

The digital news media was hit hard in the last one year. On October 3, 2023, six months before the announcement of general elections in the country, a posse of officers of the Special Cell of the Delhi police raided the office and home of the founder of web news portal NewsClick, Prabir Purkayastha who, along with his physically challenged Administrative Officer Amit Chakraborty was arrested and booked under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA).

More than a hundred locations were searched and electronic devices like phones and laptops seized from the homes of employees, ex-employees, consultants and contributors. A total of 46 people were questioned for hours and some repeatedly. Some were interrogated by the Central Bureau of Investigation. No seizure memorandum was issued or hash values given of the seized data. The Indian Journalists’ Union (IJU) said, “the seizure of mobile phones and laptops of journalists without due process puts their sources of information, which at all costs must be protected, at great risk.”

The Enforcement Directorate registered a case against the NewsClick founder, alleging that the portal had received foreign funds in violation of the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act. These raids followed a report in the New York Times (NYT) that had alleged that NewsClick had received funds from an American millionaire for carrying out pro-China propaganda in India. In short, he was accused of anti-national activity. Senior Indian journalists as well as media organisations were critical of the NYT report which they felt was based on speculation without any evidence.

The repeated hounding of the news portal has been ongoing since 2021, with multiple central agencies raiding and searching the offices of NewsClick and Purkayastha’s home, and seizing equipment. Several journalist organisations, unions condemned the raids on the web portal and demanded Purkayastha’s release. The IJU and the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) condemned the raids and the arrests. They said that while due process should be applied, the government should desist from a witch-hunt. In a joint statement, the Press Club of India, Press Association, Indian Women’s Press Corps, Delhi Union of Journalists, Kerala Union of Working Journalists and The Working News Cameramen’s Association (WNCA) condemned the use of the draconian UAPA. The seizure of equipment sans any guidelines, they said, was a direct attack on the right to livelihood.

In October 2024, 18 press bodies wrote to Chief Justice DY Chandrachud, raising concerns about the shrinking media freedom in the country, following the raids on NewsClick. The letter said that confiscating mobile phones and computers of journalists without ensuring the integrity of their data violates the basic protocol and that subjecting journalists to a “concentrated criminal process” only because the government does not approve their reportage, is a threat to freedom of the press.

NewsClick, like several other media outlets, had reported on important developments in recent years like the year-long historic farmers’ protest, uncounted deaths due to Covid-19, protests against the controversial Citizenship Amendment Act and other people’s movements. Its contents covered a wide gamut of issues, national and international, including foreign policy. In short, there was nothing that NewsClick alone was exclusively covering. During the raids and searches, reporters and contributors were asked why they were critical of the government and its policies or why they were critical of the prime minister and so on.

More reprisal was to follow. In November, NewsClick’s bank account was frozen, thereby hindering the disbursement of salaries to the staff. Many of the staff and administrative members were single earners from middle class backgrounds. The Delhi police after seeking repeated extensions from the court filed an 8000-page charge-sheet on March 30 naming Purkayastha and the company PPK NewsClick Studio Limited as accused. Meanwhile the employees of NewsClick continue to be largely unemployed with some of them looking for options even outside journalism. Purkayastha and Chakraborty continue to be in jail.

“The seizure of mobile phones and laptops of journalists without due process puts their sources of information, which at all costs must be protected, at great risk.”

Indian Army personnel patrol near Imphal in Manipur on June 20, 2023, during ongoing ethnic violence in the north-eastern Indian state. Journalists and media workers have faced detention, assault and harassment from both security personnel and civilians, with internet blockages and restrictions to information seen throughout the clashes. Credit: AFP

Use of spyware

If raids and ‘searches’ were not enough, some journalists in India found that their equipment was infiltrated by spyware. A new investigation by Amnesty International and Washington Post in June 2023 said that the Indian government had renewed the use of the invasive Pegasus spyware to target the i-phones of high-profile journalists. Among them were founder editor of the Wire, Siddharth Varadarajan and Anand Mangnale, South Asia editor of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project.

The head of Amnesty’s Security Lab noted that “increasingly journalists in India face the threat of unlawful surveillance simply for doing their jobs, alongside other tools of repression including imprisonment under draconian laws, smear campaigns, harassment and intimidation…despite repeated revelations, there has been a shameful lack of accountability about the use of Pegasus spyware in India which only intensifies the sense of impunity over these human right violations.”

Reporting conflict

Manipur in northeastern India, a state of many ethnicities and several decades-long armed conflict, saw a peak in armed violence in May 2023. The trigger, a court order that paved the way for quotas for the dominant Meitei community residing in the plains, set off a violent confrontation with the hill-dwelling Kuki-Chin tribes. Amidst the killing, rioting, sexual violence and forcible evictions, the governments of both the centre and state stood by, blocking access to information, shutting down the internet and curbing free movement of journalists. Journalists became polarised on ethnic lines, and reporting was not without bias. There was a concerted effort by the government in power at the centre and the state to control the narrative. A team of the Editors’ Guild of India which prepared a fact-finding report, was criticised for being partisan, and not following the tenets of journalism. The government filed a First Information Report (FIR, or police complaint) against the fact-finding team of the Editors’ Guild. Brooking no ‘outside’ interventions and investigations, it had previously filed FIRs against members of a women’s fact-finding team.

The IFJ urged the local authorities to withdraw the charges. The Press Club of India (PCI) and the Indian Women’s Press Corps (IWPC) too issued separate statements of support to the Guild as an apology had been issued by the authors of the report for an inaccuracy. None other than the Manipur chief minister alleged at a press conference that the Editors’ Guild report would “provoke clashes.’ The allegations from Imphal-based media against national or metro-based media of publishing/ airing one-sided news and counter-allegations by the outside media against Imphal-based local media of publishing biased news shows how the media was divided.

On May 22, 2023, three Manipuri journalists despite presenting their media credentials, were physically assaulted by security forces while covering unrest in New Checkon, Imphal. The IJU, All Manipur Working Journalists’ Union (AMWJU), Editors’ Guild (Manipur) and the Manipur Hill Journalists Union condemned the incident. An apology was issued to the journalists.

On October 11, 2023, the government issued an order restraining the sharing or videos and images of acts of violence in Manipur. Even being in possession of such videos was deemed to be an offence. The IFF wrote to the Commissioner (Home) Manipur stating that it was unconstitutional to do so as it not only limited freedom of expression but prevented citizens from being aware of potentially dangerous situations. Amidst the circulation of morphed and inflammatory videos, it became impossible to sift fact from disinformation due to the clampdown and lack of connectivity, as well as prohibitions on travelling on the ground. The internet was shut down from May 3, 2023, until December, and lifted in selected districts thereafter.

Manipuri journalists continued to be targeted. On December 29, 2023 Wangkhemcha Shyamjai, chief editor of an eveninger was arrested for publishing an article on December 12 that was “likely to cause communal disharmony and tension.” Shyamjai was a former president of the AMWJU, and his arrest was condemned by the union, as well as other journalist bodies. He got bail on December 31. In January 2024, Dhanabir Maibam, editor of Imphal’s Hueiyen Lanpao was accused of criminal conspiracy and violating various clauses of the Official Secrets Act.

The government filed a First Information Report against the fact-finding team of the Editors’ Guild. Brooking no ‘outside’ interventions and investigations, it had previously filed FIRs against members of a women’s fact-finding team.

A screenshot from Social Media Platform ‘X’, formerly known as Twitter, displays a message indicating that access to the account of Kashmiri publication Kashmir Walla has been restricted in India in response to a legal demand. Indian authorities frequently employed restriction and blocking orders on social media platforms over the past 12 months. Credit: X / Twitter

Online platforms face pressure

In August 2023, days before the Kashmir Walla’s editor Fahad Shah’s bail application was coming up for hearing, the news portal’s website was blocked and all social media sites blanked out. Their service provider informed them that the website had been blocked by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology. Websites can be blocked under 69 A of the IT Act on grounds of security of state, friendly relations with foreign states, public order or prevention of incitement to offence etc. The Kashmir Walla’s Facebook and Twitter pages were also blocked. Journalist organisations like the PCI, Press Association, the Indian Women’s Press Corps (IWPC), and the Network of Women in Media, India (NWMI) demanded the restoration of all the social media handles of the news portal.

The Kashmir Walla describes itself as a Srinagar based independent news site covering developments in Jammu and Kashmir for the last 12 years. Their founder editor Fahad Shah was arrested February 2022 for the allegedly incorrect reporting of an ‘encounter’ involving the security forces and booked under the draconian UAPA and Public Safety Act. Sajad Gul, a trainee reporter from the same organisation was also arrested. Both Gul and Shah were given bail after almost two years in jail. In November 2023, Fahad Shad walked out of jail after 600 days of incarceration.

On February 27, 2024, YouTube terminated the rights of Media Star World, a popular channel. After the DUJ appealed to YouTube to restore the channel, it complied. The DUJ also requested YouTube to be transparent as arbitrary closure of a channel was a blow to both ‘democracy and free speech.’ In January 2024, a Delhi High Court allowed a blogger-journalist Shyam Meera Singh to upload his video (after it was taken down from all social media platforms) on a controversial godman along with a disclaimer. Another news portal called Bolta Hindustan was taken off YouTube in the first week of April after the Information and Broadcasting ministry raised objections citing the IT Act and Rules. Earlier, the portal’s Instagram account was also taken down. The Facebook page of Article 19, another news portal, was restricted in February this year on grounds that it did not follow “community standards.” Most of these news portals have been critical of the central government.

Documentary filmmakers also faced similar pressures. The screening of a documentary titled ‘Kisan Satyagraha’ on the year-long farmers’ protest held at the borders of Delhi in 2020-21 was not permitted at the last minute at the 15th edition of the Bangalore International Film Festival allegedly following instructions from the Union Information and Broadcasting Ministry.

Less free and unemployed

In July 2023, the Delhi-based Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) and its research unit Lokniti released a report titled ‘Media in India: Trends and Patterns’. The Lokniti-CSDS report was based on a survey involving 206 journalist-respondents representative of gender, language background, print, digital and electronic media. The survey revealed that three out of four journalists believed that news channels were less free to do their jobs in the current climate. Fifty-five per cent of journalists expressed a similar sentiment about newspapers. Nearly 82 per cent believed that the media favoured the ruling party. The survey revealed the adverse impact of media jobs on the mental and physical health of journalists. Seven out of ten journalists experienced mental stress due to the demanding nature of the profession. Women journalists were found to be more mentally affected due to work-related stress as compared to their male counterparts.

The large number of media persons who were laid off during and in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic were either pushed into freelance or lesser-paying work and even non-journalistic forms of work. Many continue to be out of work, though there is little assessment of the extent of the crisis. There were some who challenged their unlawful termination after the pandemic in Indian courts. Some mainstream media groups too, under the pretext of restructuring the management and division of responsibilities used the occasion to lay off employees.

In December 2023, a major media house with cross media ownership laid off 120 employees from its digital division. The terminations happened on the heels of the division of assets of the company. The unit heads were told that they had performed ‘badly’. Employees learned by word of mouth that their name was on a list. The news web portal Newslaundry that keeps track of developments in the Indian media spoke to some employees of the media house and gave details in a report titled ‘Your name is on the list’.

Seven out of ten journalists experienced mental stress due to the demanding nature of the profession. Women journalists were found to be more mentally affected due to work-related stress as compared to their male counterparts.

Rahul Gandhi, leader of the opposition Congress party speaks as he displays a foreign newspaper report on the alleged Adani Coal scam during a media briefing at the party headquarters in New Delhi on October 18, 2023. Corporate interests, political polarisation, and economic struggles have greatly impacted the capacity of independent and critical journalism. Credit: Arun Sankar / AFP

Toll on mental health

In the Lokniti-CSDS survey, when asked how their media jobs had affected their mental health, 15 per cent of respondents said they were ‘highly affected’; 33 per cent were ‘moderately affected’; 21 per cent said they were ‘slightly affected’ and less than a third, 31 per cent, said they were ‘not at all affected’. Compared to their male counterparts, only 15 per cent women journalists reported being unaffected. When asked about how the work affected their physical well-being, only 27 per cent said they were unaffected. On job security, three in five respondents said that people in their organisations were told to leave their jobs to reduce costs and maintain economic stability. The English media seemed to be more adversely affected. Three out of four respondents said that people were asked to quit their jobs. To a question whether people had been asked to leave on grounds of cost-cutting and whether there had been job lay-offs or job cuts in their organisation, 61 per cent replied in the affirmative. Nearly half of the respondents especially mid-level career journalists revealed that they were more anxious about losing their jobs with women among them expressing a greater level of anxiety.

Job losses could also happen due to political leanings, ideology and opinions of journalists. Sixteen per cent revealed that they were highly anxious about losing their jobs due to their political leanings. One journalist working in a channel was sacked by the management of the TV channel for asking critical question during a press meet with the chief minister of Assam. In another case the same chief minister warned a journalist who was questioning him by threatening: “Should I call your employer to take action against you?”

Three fourths of the respondents also revealed that media houses favoured one particular political party and the ruling government. Only eight per cent believed that the opposition parties received favourable coverage and only 13 per cent believed that news was balanced.

The skew in news coverage has been growing, with more space and content allocated to the ruling party, across the media. Three out of four journalists said that ‘news channels’ were ‘less free’ to do their jobs whereas 55 per cent believed it to be so in the print media. Comparatively, only 36 per cent felt this about the online news media.

In September, 2023, the opposition INDIA alliance blacklisted 14 TV news anchors as ‘partisan’ and selected on basis of their “hateful” debates, anti-opposition narratives, attempts to black out issues of public interest, and even their social media profiles. The alliance coordination committee decided that no ban would be imposed on news channels, but the bloc’s representatives would not appear on the “hate-filled” shows of the 14 news anchors across nine channels.

While 35 per cent believed that social media was bad for journalism, television journalists more than print or digital media journalists felt that their organisations were more likely to report on trends in the social media while preparing their news content.

The survey revealed disturbing facets of trolling on social media. Two-thirds of the respondents reported having experienced trolling and online harassment on social media for their posts. Women journalists faced more trolling than their male counterparts, with 75 per cent of women journalists in the sample reporting having experienced online abuse. They said they felt extremely unsafe on social media platforms. The survey revealed the immense job insecurity journalists face across the spectrum and the mental and physical stress associated with it. The reluctance of most of them to express their views on social media platforms for fear of losing their jobs is reflective of the general state of the Indian media today.

Fear of missing out

The growing influence of social media trends on news content puts pressure on journalists to constantly keep abreast of the latest news developments, many of which are also unverifiable. The ‘Fear of Missing Out’ pressure undoubtedly comes from the top by the media owners who exert pressure on editors to get their reporters to get that ‘exclusive’ on a daily basis.

Almost every television channel carries a ‘ticker’ that announces even the most mundane of happenings as ‘breaking news’. Even in print media, journalists are expected to have Twitter handles, tweet their stories, tweet breaking news – all in order to keep up with the trends and grab more eyeballs, for their organisation. Within the same pay packets, they are expected to multi-task on various fronts just so that they don’t miss out on the ‘big’ stories, ending up doing unpaid labour.

Nearly half of the respondents especially mid-level career journalists revealed that they were more anxious about losing their jobs with women among them expressing a greater level of anxiety.

Tamil Nadu journalist and publisher Badri Seshadri (C) stands outside a court surrounded by legal representatives and supporters in Junnam after attaining bail on August 1, 2023. Seshadri was arrested for his allegedly provocative remarks against the Chief Justice of India, and was one of dozens of journalists arrested in India for their comments and coverage. Credit: X / Twitter

Attacked and arrested

In May 2023, a freelance journalist Sakshi Joshi was assaulted and placed in detention while covering a wrestlers’ protest in Delhi. The IFJ, its affiliate IJU and Digipub, a coalition of digital news media organisations, condemned the incident. IFJ urged the Indian authorities to ‘swiftly investigate the harassment and ensure that journalists, particularly women journalists are able to work free of harassment and intimidation.”

Some journalists paid the ultimate price for their work. On June 27 2023, the body of Abdul Rauf Alamgir, an Assam-based journalist with TNL, a news portal, was found. On July 10 2023, Shivam Arya, a Madhya Pradesh based journalist was abducted, shot at and stabbed.

In August 2023, a journalist, Vimal Kumar Yadav was shot dead by four people in Raniganj district, Bihar. The reporter from Dainik Jagran, a popular Hindi daily, was a witness to his younger brother’s murder by the same people. Despite giving a written complaint of the threats issued to him, the state government did little by way of giving him protection. In December 2023, the DUJ expressed concern about threats to Ashutosh Chaturvedi, the editor of Prabhat Khabar, a prominent Hindi daily. The threats were apparently issued from jail.

On March 21, 2024, while covering the arrest of the Delhi chief minister, photojournalists were roughed up by senior police officers. There was video footage of one photo-journalist being grabbed by the throat. Another cameraman fractured his elbow. Media organisations condemned the behaviour of the police.

In July 2023, four media persons were arrested in Andhra Pradesh for airing investigative stories. The IFJ and its affiliate IJU condemned the arrests and demanded authorities to respect the freedom of the press. In the month of August 2023, a Tamil Nadu journalist and publisher Badri Seshadri was arrested for provocative remarks against the Chief Justice of India. In the same month, a Maharashtra based journalist was assaulted by a group of men owing allegiance to a local legislator. Eleven Mumbai journalist bodies petitioned the Governor demanding action against the legislator. Non-cognisable complaints were filed against the persons. In September, Debmalya Bagchi, an Ananda Bazaar Patrika journalist was arrested for reporting on illicit liquor trade. The IJU and the National Union of Journalists, India (NUJI) condemned the arrest.

In October 2023, after 15 years, the killers of journalist Soumya Vishwanathan were brought to justice. In 2008, Vishwanathan, a journalist with Headlines Today was shot dead on her way home in a suspected robbery. Her killing brought into sharp focus the insecurity that women journalists faced in even in the capital.

Coming together

Indian media is passing through a churn. The churn is happening in a very polarised atmosphere where freedom of thought itself is under the scanner. What provides a glimmer of hope is the coming together of journalist organisations to protest against attacks on journalists, subtle and overt forms of harassment and the hounding of the media community by agencies of the state.

Journalist organisations across the country firmly believe that new forms of regulations by the government under the pretext of curbing disinformation or protecting sovereign interests must not be used to muzzle the media. There is also the realisation that self-censorship is not healthy and if democracy has to be defended it can only be done if the media is protected and allowed to function independently by all the stakeholders.