South Asia’s Media Viability and Trust Issue

Journalists, media workers, and supporters hold placards during a candlelight vigil outside the Mumbai Press Club in Mumbai on October 5, 2023, condemning the arrests of NewsClick founder Prabir Purkayastha and HR head Amir Chakraborty on October 3, raids on the outlet’s offices, and the questioning of a further 46 journalists. Their arrests under the notorious Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act represent one of the latest punitive crackdowns on free expression and critical voices online. Credit: Indranil Mukherjee / AFP

What does the media in South Asia comprise of today? Paid content masquerading as reportage. Social media posts masquerading as ‘real news’. Journalism decried as ‘fake news’. Press freedom as a window dressing, with media blackouts on issues like enforced disappearances and struggles for self-determination. Social media blockades; laws weaponised against journalists. Troll armies attacking journalists on social media, with women particularly targeted. Journalists self-censoring or leaving the profession. Media outlets facing financial crises. Corporations buying up media houses. Journalists sent out to report with little or no training or editorial oversight. ‘Citizen journalists’ bearing witness without context or verification. Partisan journalists and social media users at loggerheads. Amidst this chaos, journalistic values, ethics and responsibility have never been as critically needed as they are today – globally and specifically in South Asia.

Viability and sustainability of the media are closely linked to the public’s trust and credibility of news. A prerequisite of viability is an economic and political environment that enables independent media to function. Such conditions are lacking in most parts of South Asia.

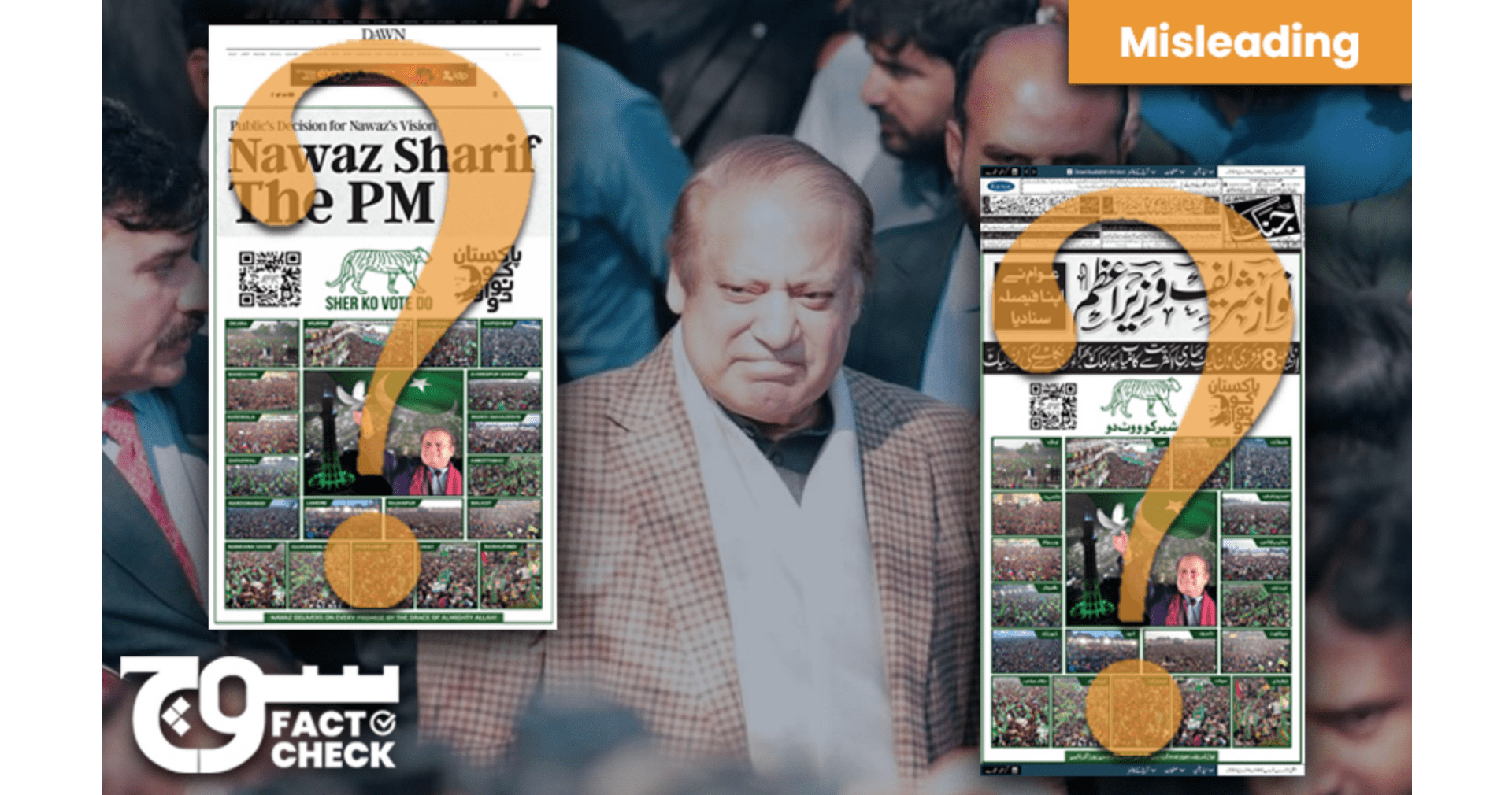

“Nawaz Sharif the PM” declared a front-page banner advertisement in both Urdu and English, of major legacy newspapers in Pakistan, a couple of days before the country’s general elections on February 8, 2024. Above the declaration of victory was the proclamation: “Public’s decision for Nawaz’s vision”. In the centre of the page, is a line drawing of a tiger with the following words below: ‘Sher ko vote do’ (Vote for the tiger). The ‘sher’, an Urdu word used interchangeably for lion and tiger, is the electoral symbol of the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz political party led by former twice-elected prime minister Nawaz Sharif. He was last ousted in a miliary coup of 1999 that gave Pakistan its third, over decade-long military dictatorship. To the left of the tiger is a QR code and to the right, another slogan: ‘Pakistan ko Nawaz do’ (Give Pakistan Nawaz). Sharif recently returned to a politically fraught Pakistan after four years in exile.

These headlines and more text with photos of political party leaders took up the entire front page of not one, but most of Pakistan’s leading legacy newspapers. These were advertisements, paid for by a political party. Resource-strapped newspapers, desperate for revenue, accepted the advertisement which landed with the marketing departments late at night.

English language newspapers tend to change the font of text-heavy ads to differentiate them from the paper’s own reporting. The only paper to carry the ad on its back page was the English-language daily Dawn, which has a policy barring front page advertisements larger than a quarter-page. But the paper violated other policies, like letting the advertisement go without an editorial overview. The political party had sent it late at night, and the marketing department pleaded not to hold it back since it adhered to Dawn’s policy of allowing political parties to praise themselves and their own performance, without attacking rivals.

Irate Pakistanis in the country and diaspora took to social media against the ‘fake news’ of Nawaz Sharif being declared prime minister even before the polls. Posts with photos and videos of the newspapers went viral, the outrage multiplying with each forward and re-share.

Few saw the distinction between a paid advertisement and genuinely reported news content. The legacy media in Pakistan, like media elsewhere which is already facing a credibility crisis, took another major hit.

The outrage, however, proves that Pakistan’s “newspapers are alive and kicking, and still have an impact,” said Sarmad Ali, managing director of the Jang Media Group in Pakistan, and also secretary general of the All Pakistan Newspaper Society (APNS).

Such full-page ads are not unique to Pakistan, according to Ali. The New York Times and International Herald Tribune have carried full front-page ads, as have papers in the Gulf states, United Kingdom, Malaysia and Bangladesh. It is particularly common in India, he added. Ali agrees that full disclosure would increase journalistic credibility “but why would an advertiser or political party pay for such content then?” he asks.

In Pakistan, online news traffic is increasingly taking the Facebook route, but local media are unable to tap the traffic for revenue generation. Various studies have found that social media algorithms disadvantage local channels or platforms, and Meta and Google algorithms prioritise international media. Thus the presence of “big tech” in the digital sphere tends to encroach on both audiences and ad revenue from local news organisations.

With over-dependence on government advertising, it is apparent that it is a challenge to uphold one of the first conditions for a viable media eco-system. What UNESCO terms a “political and social environment that enables journalism to perform its role as a public good” under its “media viability indicators” does not exist in Pakistan and most of its neighbours. Indeed, the indicators of viability are precarious at best and non-existent at worst across South Asia.

Various factors that indicate healthy media-economy-politics relations are largely absent in most parts of the region. According to UNESCO, these include a supportive economic and business environment; the structure and scope of the media economy; the media labour market; the financial health of media operations including advertising revenue; the capital environment for media operations; organisational structures and resources supporting financial and market sustainability and the media’s contribution to the national economy. The Media Development Investment Fund (MDIF) media viability survey put success along six key strategies: putting the business of media as high as editorial; a lean or flat organisational structure ie no waste; a clearly defined brand and audience; diversified revenue; finding new and creative ways to connect; and being open to change.

The crisis of viability and sustainability in legacy media across South Asia has seen many media houses pivot to digital-only publications, and even print publications move towards ‘digital-first’ editions – an acknowledgement of the sea change brought about by the rise in online platforms and digital media.

A pre-requisite of viability is an economic and political environment that enables independent media to function. Such conditions are lacking in most parts of South Asia.

Various studies have found that social media algorithms disadvantage local channels or platforms, and Meta and Google algorithms prioritise international media.

A graphic displays former Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif interlaid with full, front-page advertisements for the Pakistan Muslim National League-Nawaz in leading domestic newspapers, with text claiming that the public had chosen Nawaz’s ‘vision’. The layouts were criticised for failing to distinguish between paid and regular content, demonstrating struggles in Pakistan’s media balancing sustainability and ethical concerns. Credit: Soch Fact Check

Going digital

Digital media has changed the media landscape across the world at bewildering speed. There has been a largescale move away from print publications, broadcast and radio to the online space. This digital disruption has majorly changed the production of news, its filters and editorial oversight, as well as how audiences access content and how revenue is generated.

While digitisation has “democratised” the media, says senior Indian journalist Tarun Basu in New Delhi, it has also “killed the old model – everyone has access to the news at the same time”.

This is far from the years when legacy media outlets and terrestrial television channels were the only game in town for news consumers.

Today there are even fake pages impersonating legacy media outlets. And they have thousands of followers. For instance, a Facebook page calling itself Dawndigital.tv uses the same font as the Dawn media group, one of Pakistan’s most credible media outlets. The fake page has 15,000 followers and promotes a particular political party.

In India, legacy publications have also gone digital, entering the arena of several digital-only publications. In Jammu and Kashmir, which has witnessed a decades’ long separatist movement, “journalism is all but dead”, says Anuradha Bhasin, managing editor of the Kashmir Times, Jammu and Kashmir’s oldest newspaper. In November 2023, the editor shut down its print edition and the paper is now only available online. Currently on a journalism fellowship in the US, Anuradha Bhasin has been experimenting with different formats for the Kashmir Times, finding “new ways of storytelling” and no longer focusing on the 24/7 breaking news model.

While journalism has long been difficult in Jammu and Kashmir and the situation continued after August 2019, when the Indian government abrogated Article 370 of the Indian Constitution, stripping the state of its special status.

A BBC report in August 2023 analysed how dozens of papers in Kashmir published a daily government press release. “Nearly all had the release on their front pages, some had edited it, others carried it verbatim. The rest of the front pages were covered with statements from the government or security forces. There were many feature stories but barely any journalism holding the government to account.”

Dynamic independent media start-ups in India launched in the past decade or so are small ships with professional crews, bravely navigating repressive governments, precarious economies and challenging markets. In India, Newslaundry, The Wire, Scroll, The News Minute and subject-specific portals such as Live Law, fact-checking portals such as Boom Live and Alt News are doing cutting-edge journalism on shoe-string budgets, depending on small grants, subscriptions, donations and brand management.

More encouraging are the YouTube channels in India run by respected journalists from broadcast media. Prominent broadcast journalists like Ravish Kumar and Barkha Dutt formerly with NDTV, Abhisar Sharma and Bhasha Singh have a faithful following that also allows some degree of monetisation. In Pakistan, Naya Daur TV launched by senior journalist Raza Rumi, and in Nepal, Setopati launched by Ameet Dhakal and Barakhari by Prateek Pradhan – both former newspaper editors – with dedicated audiences are emerging as credible sources for news as well as long form, investigative stories.

Social media has become a major channel to receive news, with ‘WhatsApp University’ as Ravish Kumar pejoratively terms it, becoming a significant player in public discourse in South Asia, home to a quarter of the world’s population.

Yet, regulation of social media is a double-edged sword in the hands of authoritarian governments and “big tech” platforms.

Today there are even fake pages impersonating legacy media outlets. And they have thousands of followers. For instance, a Facebook page calling itself Dawndigital.tv uses the same font as the Dawn media group, one of Pakistan’s most credible media outlets.

A BBC report in August 2023 analysed how dozens of papers in Kashmir published a daily government press release. “Nearly all had the release on their front pages, some had edited it, others carried it verbatim.

Indian paramilitary troopers patrol past a cut-out of India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Srinagar on December 11, 2023, after India’s Supreme Court upheld an order abolishing Jammu and Kashmir’s (J&K) special status within the Union’s constitution. Since the revocation of J&K’s special status in 2019, independent journalism has been made near-impossible, with several legacy and emerging news outlets shuttering or rolling back operations. Credit: Sajjam Qayyum / AFP

New media under fire

But being digital is no safeguard, even in mainland India, where digital portals face take-down notices and others forms of censorship. Most recently, the independent news portal NewsClick, which has stood tall in covering issues ignored by the mainstream media, such as protests by farmers, Dalits or indigenous people, has been the target of raids, by the Enforcement Directorate for alleged economic offences, and its editor and another staff member detained under the draconian anti-terror law, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. NewsClick and its funders have refuted the allegation of accepting funding for pro-China coverage, charges based on a thinly-researched article in the New York Times.

Journalists and editors from The Wire, Scroll and Alt News have been subjected to raids by various government agencies, criminal charges, defamation cases, and surveillance. In April 2023, the Government of India notified amendments to the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 meant to tackle ‘fake news’ is being seen as a form of censorship, with the government assigning to itself the power to decide what is ‘fake’. Social media companies are obliged to take down content thus identified or risk losing their “safe harbour” protections in Section 79 of the IT Act, which permits intermediaries to avoid liabilities for what third parties post on their websites. Evidently, the account blocking and take down requests have been numerous enough for the social platform X (formerly Twitter) to publicly differ with the Indian Government. The accounts and posts were withheld as ordered, but the platform said, “we disagree with these actions and maintain that freedom of expression should extend to these posts”.

Similar patterns are evident in Bangladesh, where the Digital Security Act of 2018, later replaced by the Cyber Security Act, is being weaponised against journalists. In Sri Lanka, a similarly ‘draconian’ Online Safety Act was enacted in January 2024. Analysts believe it is aimed at ensuring that the kind of protest movement that toppled the government in 2022 does not arise again.

Crackdowns also affect non-journalistic users in the digital sphere, who often share material without filters or verification as governments across the region also register cases against Facebook or Twitter (now X) posts that allegedly go against the ‘national interest’ or a religious ideology.

The independent news portal NewsClick, which has stood tall in covering issues ignored by the mainstream media, such as protests by farmers, Dalits or indigenous people, has been the target of raids, and its editor and another staff member detained under the draconian anti-terror law.

Hindi-language journalist Ravish Kumar, shown in documentary While We Watched, resigned as an anchor from NDTV to start a successful YouTube channel, following the station’s ‘hostile’ takeover. Credit: Britdoc Films

Fragile freedom

At present, Nepal is “a beacon of hope in the region” in terms of press freedom, said Kunda Dixit, publisher of weekly English language Nepali Times that he launched in 2000. He was among those who had to flee the country to avoid arrest in 2016-18 during politically motivated attacks. “It’s a fragile freedom… there’s always a danger that the dark times could return.”

Currently the press in Nepal is relatively free. There are investigative stories in the mainstream media in Nepal exposing major scandals, but “the politicians know that the mainstream media don’t matter so much. The real worry is social media. The danger, as elsewhere, is the dire financial crisis, publishers not paying salaries, and media being vulnerable to corporate control.”

Now used to an independent media, “the Nepali people will push back” against any crackdown, Dixit predicted. “We have to remain vigilant. Press freedom is like a rubber band. You have to use it and stretch it to make it work.”

The country has seen a rapid rise and an equally rapid fall in digital start-ups, with sustainability being a major factor. In October 2023, a dozen digital media portal publishers came together to form a Digital Media Society to work towards more professionalism and sustainability of online media in Nepal.

The influx of technology and the scramble to convert media into paying enterprises are global phenomena that also impact the media in South Asia.

Many newspaper owners in India have other business interests, and editorial independence is fragile, factors that influence press freedom. There is also the sociological bias of those in leadership positions in media houses, says Sushant Singh, currently a consulting editor with The Caravan and a teaching fellow at Yale University. Most are male, belong to the upper castes, and buy into the idea of a ‘strong Indian state’ which leads to an “unnatural support for ideology”.

Journalists, particularly those working with smaller local language media houses in small towns, are also vulnerable to intimidation by draconian laws for national security. The resulting self-censorship is another factor that contributes to distrust in the media.

“Everyone speaking out in India knows the consequences. They are aware of risks to their safety and security that their journalism can attract. At one level, it is madness to speak out in this situation, but many do,” says Singh.

Another threat to media credibility is that business enterprises in India are buying up media outlets. And when those enterprises are close to the government, it leads to even more mistrust.

In January this year, Adani Enterprises, owned by Gautam Adani raised its stake in the Indo-Asian News Service (IANS) to 76 per cent (INR 50 million) having acquired it in December 2023. In December 2022, the group had taken over the pioneering news broadcaster NDTV, and before that, Quintillion Business Media.

The ‘hostile takeover’ of NDTV prompted one of station’s star anchors, the widely watched Hindi-language journalist Ravish Kumar, to resign and start his own YouTube channel, which now has over nine million subscribers. His story is now the subject of a documentary, While We Watched, which backdrops on the “existential crisis in truth-telling worldwide”, according to The Guardian. Kumar is just one of the many broadcast journalists around South Asia who were pushed out of television channels and launched their own YouTube channels. With proper ‘monetisation’ this is emerging as an alternate way of earning a livelihood and also reaching audiences. But it is “precarious” as Kumar pointed out during his speaking tour at American universities last year. Governments can shut down YouTube or block Internet sites at will.

Television may be dying, but there’s a surge in digital media. In India, the world’s biggest media market, digital is set to overtake TV in revenues by the end of 2024, according to a report by the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry (FICCI). India’s media and entertainment sector grew by 8 per cent in 2023, reaching INR 2.3 trillion (USD 27.9 billion), 21 per cent above its pre-pandemic levels in 2019, says the report: “70 per cent of this growth stemmed from new media, which now constitutes 38 per cent of the sector”.

In order to buck the trend of digital start-ups riding the wave but fast vanishing, digital news media portals that are here to stay have realised that collaboration is the key to sustainability. The DIGIPUB in India and DigiMAP in Pakistan have merged out of a felt need for joint action against government high-handedness and over-regulation.

The real worry is social media. The danger, as elsewhere, is the dire financial crisis, publishers not paying salaries, and media being vulnerable to corporate control.”

In order to buck the trend of digital start-ups riding the wave but fast vanishing, digital news media portals that are here to stay have realised that collaboration is the key to sustainability.

Incoming Maldivian president Mohammed Muizzu speaks during an interview with AFP in Male on November 13, 2023. IFJ research revealed that a majority of survey respondents found that the media had contributed to political polarisation. Credit: Ishara S. Kodikara / AFP

Declining trust

The media face a “trust issue” because they’ve been weakened economically by “the theft of advertising” by Google and other platforms, said Kanak Mani Dixit, founder of Himal Southasian magazine. He outlines how “advertising is down to a pittance, hence power brokers who have the money call the shots.”

The Covid-19 pandemic worsened an already dire situation for many media outlets as cash-strapped companies cancelled advertisements and readers no longer wanted physical copies of printed publications. The biggest challenge is survival. In post pandemic Pakistan, with two-fifths of media jobs lost, unemployment, under-employment and non-payment of wages stalk the media industry which continues to face dire straits. Meanwhile, attacks from all sides of the political spectrum are another challenge that legacy media outlets and journalists face in this age of ‘outrage culture’.

In this situation, there is an even greater need to contextualise the impact of increasing sensationalist news, images and videos being spread on social media and through WhatsApp. Many of these are doctored clips or propaganda from one side or another. As for the ‘trust deficit’, legacy media are perhaps no longer as “independent” as readers would like them to be, says Zaffar Abbas, editor of the Pakistan daily Dawn. People get a lot of instant news from social media posts and WhatsApp forwards, but there is hardly any cross-checking of the veracity of such posts, shares and forwards.

A 2019 study by global market research company IPSOS found that trust in traditional media declined over the previous five years. Two factors were found important: rampant fake news and doubts about media sources’ good intentions. India was found to have a high degree of trust in newspaper sources.

Other studies, such as by the Reuters Institute’s Trust in News Project (2023) also found that of the four countries surveyed for the report, the Indian public has the highest trust in the media: 65.6 per cent of Indians said they trust news ‘somewhat’ or ‘completely’, followed by USA (47.1 per cent), then Brazil (39.8 per cent) and UK (38.3 per cent). Interestingly, the level of trust decreases further down the social hierarchy with the “upper castes being the most trusting of information from the news media”. Socially marginalised ‘Other Backward Classes’ are three percentage points lower and the former untouchables the ‘Scheduled Castes’ and Indigenous Scheduled Tribes are each “more than ten percentage points less trusting”.

Data from Statista in 2023 found that the share of adults who trust news media most was 38 per cent in India, as compared to 69 per cent in Finland and 63 per cent in Kenya. Globally, social media was seen as a less reliable source of news. The Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2023 found that young people show a “weaker connection with news brands’ websites and apps – instead coming to news via search, social media or aggregators.”

Ideally, media everywhere should have editorial processes, even if rudimentary, for verification and accountability. The reality is that this in effect can delay publication of news, by which time fake news and information without context has already made the rounds on social media, without filters. Those sharing misinformation have no obligation to self-correct or issue a correction. In comparison, newspapers are duty-bound to do this if there are errors in the information they put out.

So it is the professional journalists, with editorial oversight, who can provide the context that is crucially required. Those who most need this context often no longer read the newspapers and rely instead on social media posts and WhatsApp forwards.

But trained journalists – and their editors – are also susceptible to pressure from the noise on social media and digital platforms. And even major legacy media outlets pander to ‘clickbait’ pressure, with headlines that often don’t reflect the nuance and context that an otherwise reasonable story may contain.

An interesting correlation emerges between the Reuters report on trust in the media and the recent report, compiled by the FICCI, India’s largest and oldest non-governmental trade association and advocacy group, and Ernst and Young, India. The FICCI report finds that contrary to the global trend, the print media are still thriving in India. Advertising revenues in India grew by 4 per cent in 2023 with a significant growth in premium ad formats, “as print remained a preferred medium for affluent metro and non-metro audiences. Subscription revenues also grew by 3 per cent due to rising cover prices,” according to the FICCI press report.

Newspapers in India remain heavily subsidised by government and private advertising, with consumers paying only 20 per cent of the cost of production, according to estimates. Award-winning reporter Sushant Singh, notes that this makes the papers heavily dependent on government advertisements and vulnerable to political and other pressures.

In the Maldives, the 2023 IFJ report, “Unveiling Public Trust in the Maldivian Media” found that digital media or online news portals were the leading source of “daily” news for 67 per cent of respondents, followed by television with 53 per cent. The study, which was jointly launched by IFJ and its Maldivian affiliate the Maldives Journalists Association (MJA) found Facebook was the dominant choice of social media platforms, publishing what Maldivian people understood as “news content”. As many as 64 per cent use the platform as their primary medium to access news online.

Significantly, a key finding was related to political divisions, with the majority of respondents (87 per cent) agreeing that the media should be held accountable for political divisions in the country. According to the MJA, “Editorial independence and transparency is the biggest challenge journalists and the media face – the key to solving this is directly tied to strengthening journalists and helping organize media workers unions in the country.”

The recommendations to increase trust in media included: Increased support to ensure stronger, more sustainable media in the Maldives; efforts to strengthen editorial independence in media outlets, particularly relating to media ownership and establishing a mechanism to ensure transparency in funding for media outlets.

The biggest challenge is survival. In post pandemic Pakistan, with two-fifths of media jobs being lost, unemployment, under-employment and non-payment of wages stalk the media industry which continues to face dire straits.

Newspapers in India remain heavily subsidised, with consumers paying only 20 per cent of the cost of production, according to estimates. Award-winning reporter Sushant Singh, notes that this makes the papers heavily dependent on government advertisements and vulnerable to political and other pressures.

Supporters of India’s Congress party hold signs and symbols during a roadshow for Mansoor Ali Khan, an election candidate for Bengaluru central on April 3, 2024. Increasing threats to the world’s largest democracy by the Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party have made opposition parties, civil society and independent observers sceptical of the process’ impartiality. Credit: Idrees Mohammed / AFP

Attacking credibility

Assaults on journalists, including reputational harm, have seriously impacted how journalists work, and in turn journalistic credibility, finds a study conducted by the University of British Columbia’s School of Writing, Journalism, and Media in collaboration with the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). The findings of the 2023 study, based on the testimonies of 645 journalists in 87 countries, found that attacks included “public messages intended to discredit, delegitimize, or dehumanize journalists.” Such attacks are also launched in politicians’ speeches (reported by 72 per cent of respondents), news broadcasts, and courtrooms, the study found.

The report notes that globally, press freedom and trust in journalism appear to be on the decline, while threats to journalists’ safety – particularly women and those belonging to marginalised ethnic, racial or religious groups – are on the rise. “Journalists who faced frequent reputational attacks were more likely to have experienced harm to their mental and physical health, to have seriously considered quitting journalism, and to have relocated from their city or country to avoid or mitigate threats” found the study. Self-censorship was one of the fallouts of the attacks.

Manimugdha Sharma, one of the researchers and a former journalist with the Times of India, notes that India has the worst showing on all the parameters, and some of the respondents from India exhibited unprecedent levels of fear.

Several recommendations are put forward including the suggestion that “newsrooms, press freedom bodies and civil society organizations develop monitoring systems to identify reputational attacks and harassment targeting journalists.”

Expressions of public support and legal action against those who defame or threaten journalists are also essential. Preventive measures like cyber-security training, as well as legal and psychological assistance for journalists would also be useful. Another recommendation was for social media companies to improve their anti-abuse tools, content moderation, and capacity to assist targeted journalists.

Overall, concluded the Report, the systemic and ongoing damage to journalism and public discourse needed to be addressed in the interests of journalists’ safety and ability to promote accountability, truth-telling, and most importantly, democracy.

“However, even in these difficult times, there are few media – they tend to be online, but exceptionally some print – that have not succumbed,” says Kanak Mani Dixit in Kathmandu.

Many citizen journalists and social media users have played important roles in bringing critical issues to the attention of the legacy media. Few have the training or ability to provide the required context and nuance.

If there is an agreement that journalism is about bearing witness, providing news and information in context, being fair, and giving voice to underprivileged communities, this is a task that even non-professional or citizen journalists can participate in, Many are doing this, but often without intentionally adhering to these basic principles which professional journalists also need to keep in sight.

Towards viability

Given the struggle to survive in a harsh economic and political environment, independent digital portals are pushing the envelope and redefining viability itself. Collaboration over competition seems more workable than competing for scarce resources. In India, digital portals pooled resources to offer election coverage in May 2023, during the crucial hotly contested state elections in Karnataka. Pooling in financial resources as well as reportage, the audiences were offered real-time updates as well as informed commentary, unlike the rabble rousing that passes for ‘journalism’ in news shows on mainstream television. A similar collaboration by The NewsMinute, Scroll, Newslaundry and several independent journalists, broke some of the most significant stories in recent times, as part of ‘Project Electoral Bond” in March 2024 – an expose on the funding of political parties deemed illegal by the Supreme Court. Collaboration also offers some protection from the risk of being slapped with cases and hauled to court.

Globally too there has been new thinking around viability. Internews, Microsoft and the US Agency for International Development (USAID) have launched a new public-private partnership to develop a Media Viability Accelerator to help independent news outlets become more financially sustainable. The announcement, made ahead of the 2023 Summit for Democracy, demonstrates a cross-stakeholder commitment among government, business and civil society to support media viability.

Additionally, what if concerned institutions and individuals come together to formulate and agree on a global minimal code of ethics around basic journalistic principles like ensuring two-source verification from diverse sources, context, fairness, and non-partisanship? If this is something that professional journalists as well as social media users voluntarily endorse in large numbers, it would also help educate news consumers – many of whom are also news producers – and perhaps help correct the course of journalism today.

Several recommendations are put forward including the suggestion that “newsrooms, press freedom bodies and civil society organizations develop monitoring systems to identify reputational attacks and harassment targeting journalists.”

Globally too there has been new thinking around viability. Internews, Microsoft and the US Agency for International Development (USAID) have launched a new public-private partnership to develop a Media Viability Accelerator to help independent news outlets become more financially sustainable.

Headlines from non-profit independent digital news outlet Sapan News focusing on democratic values, human rights, and under-reported issues from across the region and the diaspora. Run by volunteers, recent efforts to fundraise may help increase the outlets sustainability long term. Credit: Sapan News

The Thought Behind the Dream

In August 2021, Pakistani journalist Beena Sarwar sent out a feature she had written to several editors she personally knew around South Asia and called it a syndicated feature from a media outlet she invented at that moment – Sapan News. Sapan was originally the acronym for a peace movement she had been involved in since March 2021 – the Southasia Peace Action Network. This in turn was built upon decades of work around human rights, dignity, and peace issues with a focus on Pakistan, India and South Asia. (Southasia as a single word is borrowed from the style book of Himal Southasian magazine, to emphasise regional togetherness).

Originally shortened as SAPAN, it began to be written as Sapan, which means dream in many South Asian languages. The dream is one of peace, cooperation, collaboration, and dialogue across regional and other divides. The Southasia Peace Network holds regular monthly online public discussions furthering this cause with area experts from around the region and the diaspora and expatriate communities.

Working with a small team of volunteers, Sarwar would send out press releases about these events that media outlets across the region regularly published. She then began sending out stories aimed at amplifying the ideas shared during these discussions. It soon became apparent that Sapan News was providing features on issues that the mainstream media tend to sideline, due to lack of human and financial resources. Sapan News has developed into an independent, syndicated media service that covers and connects South Asia, the Indian Ocean and the diaspora. Its slogan: ‘It’s all connected’.

Sapan News as a small, digital, volunteer-run, non-profit newsroom that is local, regional and global, is driven by a spirit of fairness, upholding democratic values and human dignity. Given the polarisation in societies everywhere, Sapan News tries to present different perspectives, across binaries, with well-researched, contextualised information, explainers and backgrounders and voices from the community and on the ground. An intergenerational, international and local pool of writers including industry leaders, experts, analysts, academics, activists, editors, reporters, students and multimedia journalists make up the team.

Sapan News stories connect the dots and go into the why and how of issues that tend to be overshadowed by the rush of daily news stories and mainstream narrative. They highlight the peripheries, art, culture and sports in the context of politics and produce stories that go behind the headlines with deep dives and the kind of nuance that media outlets often don’t have the time, capacity or resources to work on. Sapan News focuses on the process and context behind the news and takes the long view. Sapan News features are currently published by over 30 media outlets, including some leading digital publications around South Asia as well as in Australia and North America.

The viability of this tiny enterprise as well as its future impact is yet unknown. The crowd-funded volunteer-powered work got a boost in December 2023, after successful fundraising through NewsMatch, a philanthropic fund administered by the Institute for Nonprofit News, INN, a professional body of which Sapan News is a member. On the cards now is hiring part-time editors, paying the chief editor, covering some expenses, paying modest honoraria to some freelance contributors and training interns along the way. The journey to making a positive contribution to the media landscape has gone into second gear.