BANGLADESH

Quantity Over Quality

A young child dressed as the Hindu god Lord Krishna takes part in a celebration for the Janmashtami festival in Dhaka on August 19, 2022. Amid extreme religious polarisation, journalists and activists from Bangladesh’s minority Hindu community are disproportionately targeted by the draconian Digital Security Act. Credit: Syed Muhamudur Rahman / NurPhoto via AFP

As Bangladesh heads into a general election, likely to be held in January 2024, the atmosphere is heating up and presenting major challenges for the media. The good news is that both domestic and international stakeholders are now more vocal than ever before about protecting freedom of expression in this troubled, dynamic and complex space.

Bangladesh has achieved remarkable progress in a little over five decades since its bloody Liberation War of 1971. Since 2000, it has been among the fastest growing economies in the world. Yet, democracy and freedom of expression are being severely tested amid growing fanaticism, intolerance and political rivalry between the ruling and opposition parties.

Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, who survived harassment and attacks while in opposition, is now criticised for being too authoritarian and prioritising the consolidation of her power rather than fulfilling her obligations to democracy. She has been premier since 2009.

While the media is seemingly booming, the sharp spike in the number of media outlets presents a big challenge for the media industry, even as the government’s heavy-handed regulation of the rapidly mushrooming online portals, social media sites, newspapers and television channels adds to the challenge.

Bangladesh has 3,176 registered newspapers and magazines of which 1,279 are dailies, according to 2022 data from the government’s Department of Films and Publications. Currently the number of daily, weekly and monthly newspapers published from the capital city of Dhaka is 1,141. Of these, 509 are dailies, 345 are weeklies and 287 are monthlies. Industry insiders however say that these numbers do not represent credible media outlets. The number of authentic Bangla dailies published from Dhaka is more likely to be just 32, and fewer than 10 English dailies they say. These are publications that have offices and staff and are published every day. There are around 20 local dailies published from different districts, which maintain minimum journalistic requirements.

The mushrooming of media registered with the government website represents a spurt in quantity rather than in credible and ethical journalism.

International spotlight

The United States in its 2022 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices strongly criticised Bangladesh for “serious restrictions on free expression and media, including violence or threats of violence against journalists, unjustified arrests or prosecutions of journalists, censorship, and enforcement of or threat to enforce criminal libel laws to limit expression and serious restrictions on internet freedom”. It highlighted issues like “unlawful or arbitrary killings, including extrajudicial killings; forced disappearance; torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment by the government.”

On February 9, 2023, nine member countries of the Media Freedom Coalition (MFC), including the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Netherland, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland announced their decision to monitor freedom of press in Bangladesh. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina however announced on March 13 that she would never bow down to foreign pressure.

Media Rights Violations

Killings

Arrests

Bangladesh’s Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina inspects a guard of honour during a ceremonial reception at India’s presidential palace in New Delhi on September 6, 2022. In February 2023, Hasina refused to meet with a consortia of pro-press freedom diplomats, claiming this would compromise Bangladesh’s national autonomy. Credit: Money Sharma / AFP

Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, who survived harassment and attacks while in opposition, is now criticised for being too authoritarian and prioritising the consolidation of her power rather than fulfilling her obligations to democracy.

Unnatural deaths

Journalists in Dhaka demonstrate for justice every year on February 11, to mark the murders of journalists Sagar Sarowar and Meherun Runi on the same day in 2012. More than 11 years have passed since the ghastly double murders, but a court in Dhaka on March 5, 2023, granted – for the 96th time – the request of the country’s elite police force Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) for more time to complete the investigation.

According to the UNESCO Observatory of Killed Journalists, there are 11 unresolved cases of murdered journalists in Bangladesh. The list has a total of 26 journalists, including some bloggers, killed between 2004 and July 2022.

The year 2023 opened with the brutal killing of a journalist. Ashikul Islam, 27, district correspondent for the Daily Monitor and a reporter with local online newspaper Brahmanbaria Sangbad in Brahmanbaria district. He was hacked to death on January 9. The accused was arrested within hours, and the motive behind the murder is still being investigated.

Nine cases of unnatural deaths of journalists and media workers were registered in 2022, of which four were murders, and five were suicides according to police statements.

The body of the acting editor of the daily Kushtiar Khabar, Hashibur Rahaman Rubel, was found in a pond in Kumarkhali Upazila (sub-district) of the Southern Kushtia district on July 7, a day after he disappeared. His family and colleagues alleged that had the law enforcement agencies acted immediately after he was reported missing, he could have been found alive. The police are yet to ascertain the motive behind the killing or bring the perpetrators to justice.

On August 4, 2022, the decomposed body of journalist Golam Rabbani Saiful was recovered from a pond in Sonargaon Upazila of Narayanganj district. He was suspected to have been murdered by narcotics dealers because of his reporting on drug trafficking and live telecasts on social media, according to a report posted on matrijagat.com, website of a small daily Matrijagat where Saiful worked as a reporter. Covering the narcotics trade can literally cost reporters their lives. Barely a year ago, on April 13, 2022, Mohiuddin Sarkar Nayeem, a reporter for the local newspaper Dainik Cumillar Dak in Cumilla district was murdered. Reports suggest that narcotics dealers shot and killed Nayeem as he had unveiled their narcotics business.

On June 8, the police recovered the mutilated body of Abdul Bari, a producer of private TV channel DBC News from Hatirjheel lake near Police Plaza in Dhaka. His throat had been slit and he had visible stab wounds. After investigations, the police declared that it was a suicide.

Police recovered the dead bodies of four other journalists – three of them women – and concluded that they were suicides.

Attacked with impunity

At least ten journalists were injured in police action at the Supreme Court in Bangladesh on March 15, 2023, while covering the Bar Association election. The attack was criticised as a trampling of the constitutionally recognised freedom of the press in Bangladesh.

Satkhira-based journalist Raghunath Kha, known for his writing about the rights of landless people, was blindfolded, tortured, and electrocuted in the custody of the Detective Branch on January 23, according to a report by New Age on January 29, 2023. Raghunath worked for Deepto Television and a Dhaka-based daily as a district correspondent. He was also a factfinder with two Dhaka-based rights groups.

Abu Azad, Chattogram staff correspondent of The Business Standard newspaper was beaten up after he tried to investigate illegal brick kilns in Rangunia sub-district in Chattogram on December 25. The daily reported that the journalist was held at gunpoint by a member of a Union Parishad (UP) or local government body, kept hostage for over an hour, and beaten repeatedly. The local UP chairman threatened him over the phone. No action has been taken against these individuals. Amid such a culture of impunity, the difference between life and death is often decided by criminals.

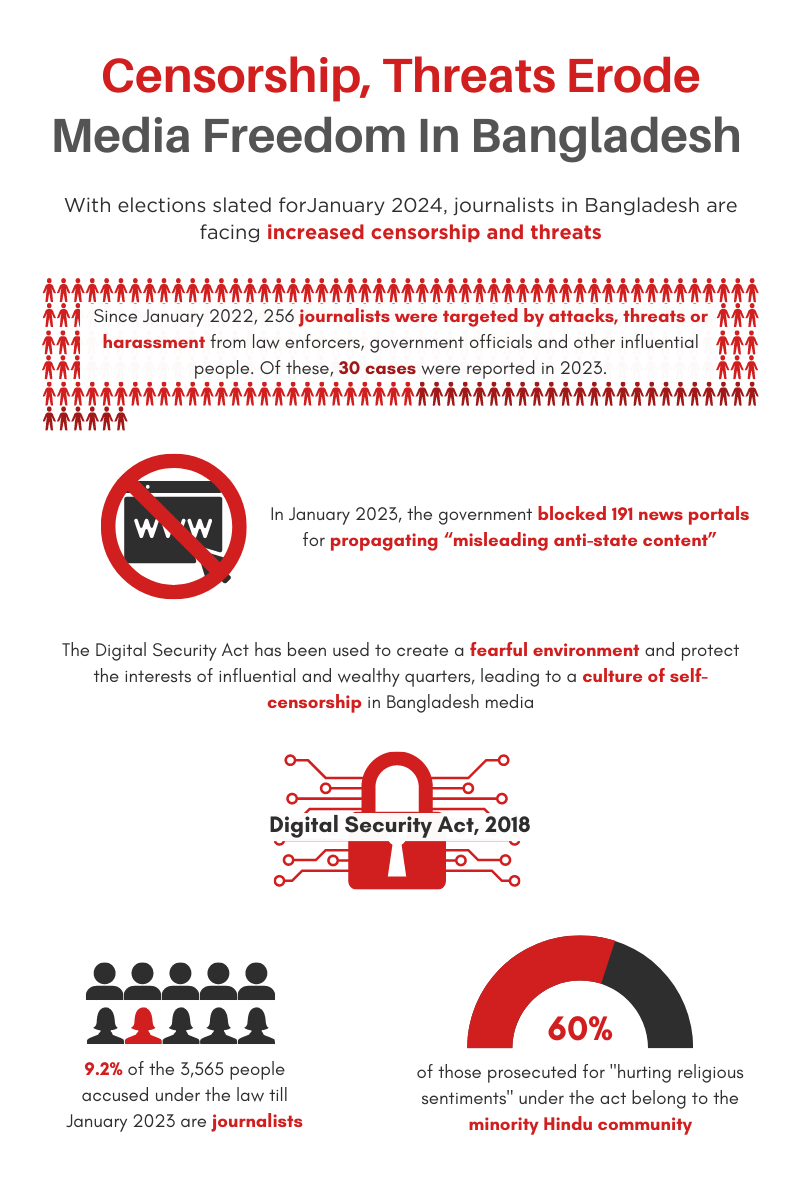

At least 226 journalists were targeted in attacks, threats or harassment from law enforcers, government officials and other influential people from January 2022 to December in 2022, according to the human rights group Ain O Salish Kendra (ASK). During the first two months of 2023, ASK compiled, based on newspaper reports, 30 incidents of harassment of journalists. These include two incidents of physical assault while performing professional duties, nine cases filed against published news and 20 cases of torture or threat by different quarters including by law enforcement agencies. (This may not be the accurate figure, as the murder of Ashikul Islam in Brahmanbaria on January 9 is missing.) Bangladesh does not have an agency to impartially monitor incidents of harassment of journalists and attacks on press freedom.

Nine cases of unnatural deaths of journalists and media workers were registered in 2022, of which four were murders, and five were suicides according to police statements.

Garments workers of Achieve Fashion Ltd stage a demonstration demanding to reopen the garments factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh, on February 27, 2023. Freedom of expression and democracy in Bangladesh continues to be challenged, particularly with the upcoming general election, set to be held in January 2024. Credit: Mamunur Rashid / NurPhoto / AFP

Forced shutdown

Information Minister Hasan Mahmud told Parliament on January 30, 2023, that the government would block 191 news portals for their role in propagating “misleading anti-state content”.

Currently, four state-owned, and 34 private broadcasters operate in the country. There are 346 online newspapers registered with the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, including 162 online news portals, 169 online portals of daily newspapers and 15 online portals of TV channels. “The 191 online portals, which are going to be blocked, are not registered. Most of them neither have an office, nor have they employed any journalist or other workers. They are operated by some groups to spread false propaganda,” said the minister.

The shutdown of Dainik Dinkal, the newspaper of Bangladesh’s main opposition party, on December 26, 2022, has been criticised as a “blatant attack on the press” ahead of the upcoming elections.

Bangladesh Press Council, a quasi-judicial body headed by a former High Court judge, rejected the daily’s appeal against the government’s shutdown order on the grounds that its publisher, Tarique Rahman, was a convicted criminal. But Shimul Biswas, the acting publisher of the daily, said that it was shut down despite the resignation of Rahman, who is also the acting chief of the opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party.

Draconian DSA

Digital Security Act (DSA) 2018, the successor of the Information and Communication Technology Act (ICT) 2006, has been consistently criticised as ‘draconian’ and a ‘weapon to muzzle political dissent, freedom of expression and press freedom.’ Although officials have claimed on several occasions that its provisions will not be used to limit freedom of expression or political dissent, cases filed so far and the treatment of the accused in the cases establish that it has been so used. The law has successfully created a culture of self-censorship in Bangladesh.

Since the law was enacted, at least 3,565 were accused in 1257 cases filed till January 28 this year. Of them 9.2 per cent accused are journalists, according to DSA Tracker, a project of Dhaka-based Centre for Governance Studies (CGS). Many of the cases filed under the DSA are politically motivated and against those holding ideologies different from the ruling establishment. Recent research by the CGS shows that the law has been used to create a fearful environment and protect the interests of influential and wealthy. A detailed study of 1,109 cases filed under the law between October 2018 and August 2022 showed that 2,889 persons had been charged, of whom 26 were minors. Of the total number of accused, 38.74 per cent were detained. Activists, members of different political parties, and journalists are mostly the defendants in these cases while it is members of the ruling Awami League and its affiliated organisations who have filed most of the cases.

A case, for instance, was filed against Pulack Ghatack, journalist and general secretary of Bangladesh Hindu Law Reform Council (BHLRC) under the DSA on October 27, 2022, for his work to ensure equal rights for Hindu women in Bangladesh.

From January 1, 2022, to March 26, 2023, data shows that cases against journalists have decreased, with only 2.1 per cent of the accused being journalists, and most cases being filed for Facebook posts.

A Cyber Tribunal in the Northern Rangpur district on February 8, 2023, sentenced Paritosh Sarkar, a teenager belonging to the minority Hindu community, to 11 years of imprisonment under four sections of the DSA and fined BDT 30,000 (USD 285) fine for a Facebook post.

Paritosh was accused of hurting the religious sentiments of Muslims through a derogatory social media post due to which an entire fishing village in Rangpur’s Pirganj sub-district had been allegedly set ablaze on October 17, 2021. This is the first conviction for the communal violence that left over 60 Hindu homes, including that of Paritosh, razed. Paritosh was arrested on the day of violence and put into solitary confinement for eight months reportedly “for his safety.”

The trigger for the arson in Pirganj sub-district in October 2021, was a viral video that showed disrespect to the Holy Quran, allegedly by Hindus. However, analysis of CCTV footage revealed that it was one Iqbal Hossain, a 35-year-old Muslim man who had deliberately placed the copy of the Quran in the Hindu temple and Facebook had been used to spread the video and incite Muslims to riot. On March 2, 2023, Dhaka’s Cyber Tribunal sentenced Iqbal to 16 months in jail, or the period he had already spent in prison, after he pleaded guilty to the charge of orchestrating the violence. Earlier the same court sentenced Rokon Mia, another accused, to jail for the period he had been in prison. Rokon wrote a provocative Facebook post five days after the incident.

The verdicts in these cases, one against Paritosh Sarkar and the two others against Iqbal Hossain and Rokon Mia, show how the police and the judiciary are interpreting DSA in a selective manner.

Hindus, who make up 7.9 per cent of the country’s 165 million population, are a beleaguered minority community in Bangladesh. Facebook and YouTube are filled with derogatory posts on the Hindu faith, but the Hindus say that they are arrested frequently for defaming Islam. According to data published by Daily Star in February 2022, 60 per cent of those prosecuted for “hurting religious sentiments” under the DSA belong to the minority Hindu community.

Spreading hatred online and offline against the Ahmadiyya, a sect within Islam, is also common in Bangladesh.

Meanwhile, commentators such as Rana Dasgupta, general secretary of Hindu Buddhist Christian Unity Council, the biggest interfaith platform of minorities in Bangladesh, and Shyamal Dutta, General Secretary of the National Press Club in Dhaka, both Hindus, have spoken up against unregulated social media. It has brought multiple challenges, they said, with which the country and the people are not ready to cope.

MA Aziz, a senior journalist and former secretary general of the Bangladesh Federal Union of Journalists said that most hate campaigns happen on Facebook and YouTube, platforms that do not have any editorial control. “But at the same time, we cannot seek to control the voice of the people on social media. We cannot support a draconian law like the DSA. We need responsible actions from all sides so that free speech is allowed in a better environment,” he said.

On February 28, a civil society platform with prominent rights activists and educationists, called for the DSA to be invoked against anyone found spreading false propaganda against science-based secular education. Earlier that month, faced with a flood of posts on YouTube and Facebook criticising two textbooks for explaining evolution in line with Charles Darwin’s theory, which the Islamists consider anti-religious, the government had withdrawn the textbooks. They were titled “History and Social Science: An Inquiry-based Reader” and were meant for classes 6 and 7.

Conducting academic discussions on scientific matters has become fraught in Bangladesh, given the need to tread carefully on religious feelings. On March 20, 2022, schoolteacher Hridoy Mandal’s science lesson in a Class 10 classroom was filmed by a student and soon went viral. Students and locals held protests outside the school demanding action against Mandal. Police forthwith arrested the teacher, who served 19 days in jail before being freed on April 10 after counter-protests by secular activists.

While Mandal’s acquittal was a relief for science teachers, it prompted secular activists to demand using the DSA against those spreading rumours against science teaching. This strong contradiction in the response to the DSA arises many times in Bangladesh and creates sharp political divisions.

There is a growing realisation about how disinformation is adversely impacting the country’s socio-political milieu and contributing to political conflicts and media crises.

A protest over the election of the Bar Association at the Supreme Court area in Dhaka, Bangladesh on April 2, 2023. Sharp political divisions in Bangladesh continue to manifest, particularly against the draconian Digital Security Act. Credit: Syed Mahamudur Rahman / NurPhoto

Attack on Prothom Alo

A group of youth barged into the Kawran Bazaar office of prominent independent Bangla daily Prothom Alo on April 10. They hurled abuses at the editor and wrote the word ‘boycott’ on the glass inside the reception. The incident happened within two hours of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s declaration in parliament: “Prothom Alo is the enemy of Awami League (ruling party), the enemy of democracy, and the enemy of the country’s people.” The new volley of attacks on the newspaper began on the country’s Independence Day on March 26, 2023, when an online report quoted a citizen saying, “What will we do with independence if there’s no food to fill our stomachs?” The report reflected the government’s failures in economic management amidst growing inflation. The leaders of the ruling party and its followers interpreted it as a mockery of the country’s hard-earned independence and as an assault on their nationalistic sentiment and let loose a barrage of criticism against the paper.

In the early hours of March 29, Criminal Investigation Department personnel in plain clothes picked up Prothom Alo reporter Samsuzzaman Shams from his home in suburban Dhaka. The court sent the reporter to jail the next day, in a case filed on the midnight of March 30 under the draconian Digital Security Act 2018, in which the newspaper’s editor was named as the main accused. The High Court granted Prothom Alo editor Motiur Rahman anticipatory bail for six weeks on April 2. The reporter was released from Dhaka Central Jail in Keraniganj on April 3, 2023, after obtaining bail in two cases filed against him over the issue.

The newspaper has since faced smear campaigns with diverse groups, including the Dhaka University Teachers’ Association, siding with the government. However, the opposition parties and their followers stood with the daily against the attempt to intimidate the management.

Shrinking labour rights

On January 8, 2023, the Parliamentary Standing Committee in the Information and Broadcast Ministry was granted another 90 days to examine the Mass Media Employees (Services Conditions) Bill 2022. The Bill had been placed before Parliament in March 2022.

Once the new law is passed, jobs of media employees will no longer be regulated under existing labour law. The wages and benefits of journalists, employees and press workers, artists of broadcast, online, and print media outlets would be fixed under the proposed law, a prospect that has been opposed by both trade unions and media owners’ associations.

As per the bill, journalists will be regarded as “media professionals”, and not as workers. The bill incorporated a provision of forming “mass media worker’s welfare samitis” (committees) curtailing journalists’ rights to union activities. It has been made a punishable offence to participate in any protest program without the media owner’s permission.

Section 12 of the proposed law gives media owners the right to terminate a journalist deemed surplus. The retrenched journalist would get one month’s salary under the proposed law while in the existing law a journalist was entitled to a salary for four months in case of termination.

Section 14 contains a dangerous provision to dismiss workers for misconduct, without providing any definition. Service benefits have been axed to half in the proposed bill. While the proposed bill increases maternity leave to six months from the existing eight weeks, the current entitlement to two gratuities for one-year of service will be cut to one gratuity, while leave has been cut to 15 days from 30 days after every three years in service.

Article 25 does not make the formation of a minimum-wage board compulsory but leaves it to the government’s discretion. Similarly, formation of future funds has been left to the owners’ discretion.

“If enacted, this law would plunge the journalist community into deep crisis and uncertainty,” Bangladesh Federal Union of Journalists (BFUJ) said in a statement on April 3, 2022. At least 37 sections out of 54 of the proposed law are believed to be against the interests of journalists.

President of another faction of BFUJ M Abdullah said that journalist’s working hours were legally fixed at 48 hours per week while for government employees it was 40 hours a week.

Violation of the Bill will attract a fine, and the government could cancel the licence or registration of the media outlet.

The Editors’ Council has said that the space for independent media will shrink further if the proposed bill is enacted. While union leaders said that the proposed law would go against the interests of journalists and protect media outlet owners, it seems that the bill will adversely impact owners as well. The Newspaper Owners’ Association of Bangladesh (NOAB) in a statement on April 24, 2022, said that newspapers would suffer and that freedom of the press would be impacted.

The proposed law calls for the establishment of media courts consisting of a working district judge, a media owner and a media worker to settle disputes over arrears. NOAB opposed this proposal on grounds that there is already a labour court for the settlement of arrears of journalists and any other dispute. In addition, the Bangladesh Press Council, formed by a retired judge of the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh, has been working to control the newspaper and protect the freedom of speech in Bangladesh. It also works to maintain and revise the standards of newspapers and news agencies and for the protection of press freedom.

Article 25 does not make the formation of a minimum-wage board compulsory but leaves it to the government’s discretion. Similarly, formation of future funds has been left to the owners’ discretion.

Journalists from the Dainik Dinkal, the opposition of Bangladesh’s main opposition party, hold a protest on February 20 in Dhaka against a government to order its forced shuttering on December 26, 2022. Just over a month later, over 191 online news portals were blocked for allegedly ‘misleading anti-state content’ on January 30. Credit: Munir Uz Zaman / AFP

Unsafe private data

The draft Data Protection Act 2022 (DPA), the first law for data protection in the country, has engendered new fears. Critics at home and abroad say that the draft law poorly defines the classification of data and does not follow international definitions of privacy. It does not mandate that privacy-related data fields be removed from telecom voice and data call records, broadband internet packets, intercepting sources, financial sources, and smartphone app crowdsourcing data.

The United Nations has shared observations and objections regarding potential human rights violations through the DPA. The UN pointed out that the definition of “sensitive data” in the draft DPA was limited – it does not include disclosure of information related to race or colour, political opinion, trade association membership, religious or other beliefs, sexual orientation, etc. The draft does not clearly define personal data and the principles of data protection stated in the fifth article are insufficient.

Section 33 of the DPA empowers the government to exempt law enforcement and intelligence agencies from the Act, which may allow surveillance of data centres and servers in Bangladesh. These provisions raise apprehensions that such a weak data protection law will protect the government’s interests and not those of the citizens.

Women in media

The media in Bangladesh is still largely male dominated. Women still must work hard to gain acceptance as professionals in the news media, although social taboos and conservative values confining women within the four walls are gradually loosening. A study published in November 2022 by Dhaka-based Management and Resources Development Initiative (MRDI), covering 18 media outlets found that 15 of the outlets offered maternity leave, nighttime transport and separate sanitation facilities for women.

However, gender imbalance in the media in Bangladesh continues. Women’s representation in newsroom leadership is poor. The study found that only two of the editors of over 500 Dhaka newspapers are women. Only two women hold top positions – as executive editor and chief news editor – at private TV channels.

The study also found that only 8 per cent of stories had bylines by women. The scenario is slightly better in electronic media. The South Asia Center for Media in Development (SACMID) monitored news reports of two television channels from April to June of 2022 and found that 71.29 per cent news presenters were women. But this appears to be a cosmetic change, not reflected in genuine gender perspectives in media coverage. The SACMID study found that the media featured women as the first character in only 20.57 per cent of the total 1122 news reports.

A long struggle

The media in Bangladesh is today confronted by complex challenges to the practice of ethical journalism ranging from obstacles to the flow of information; the lack of government will; misinformation and inadequate fact-checking; self-censorship and fear of the DSA; ineffective implementation of the Right to Information Act and the prevalence of paid content creators who circulate fake news on social media. There is unhealthy competition among media outlets, and excessive work pressure on reporters which impacts professional journalism.

One of the main contradictions in Bangladesh is that press freedom means freedom of the owners of media outlets who are corporate houses who are in turn governed by their business interests and political affiliations. Journalists are not free; they are bound to serve the interests of media owners, work for precarious pay and in insecure working conditions. Given the stupendous challenges, it is only unity among media unions and associations overcoming political polarisation, that can reinstate professional and independent journalism.

One of the main contradictions in Bangladesh is that press freedom means freedom of the owners of media outlets who are corporate houses who are in turn governed by their business interests and political affiliations.

Students hold a protest on March 30, 2023 in Dhaka demanding the release of Prothom Alo journalist Shamuzzaman Shams, charged under the Digital Security Act. Media workers at Prothom Alo have faced harassment, violence, and legal threats after Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina named the outlet an ‘enemy’ of the ruling Awami League party. Credit: Rehman Asad / AFP