SRI LANKA

Picking Up The Pieces

Protestors gather inside Sri Lanka’s Presidential Palace in Colombo on July 9, 2022, demanding the resignation of former-president Gotabaya Rajapaksa. Essential goods shortages, threats to journalists’ safety, and protest-inspired state repression of freedom of expression severely impacted Sri Lanka’s media sector in 2022-23. Credit: AFP

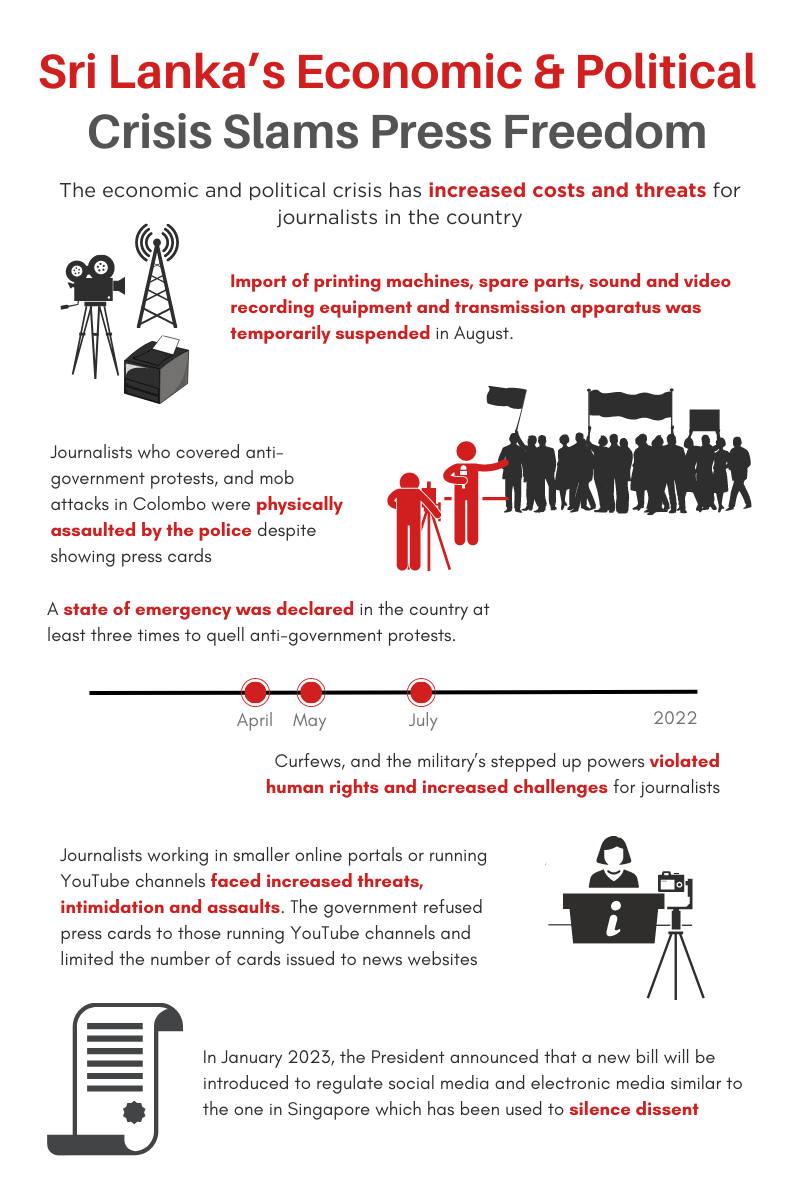

Sri Lanka’s economic crisis in 2022, with high inflation and shortages of fuel, domestic gas, medicine and other essential items, saw thousands of people take to the streets to protest. By mid-April, Sri Lanka defaulted on its external debt of more than USD 50 billion, and the shortage of foreign reserves led to several import restrictions. Reports say that around half the island’s population had to reduce their food intake and faced increased malnutrition.

A sea of protesters occupied the Galle Face Green at the centre of Colombo city, near the Presidential Secretariat and demanded the resignation of the government. After a large group of the government’s supporters assaulted peaceful protesters and destroyed their makeshift tents on May 9, large-scale violence erupted across the country.

In mid-July 2022, protesters stormed the Presidential residence and Secretariat demanding the President’s resignation. President Gotabaya Rajapakse fled the country and his political ally in the Opposition Ranil Wickremasinghe was sworn in as Prime Minister shortly thereafter, and elected President by a Parliament vote in July.

After Wickremasinghe became president, a state of emergency was declared, curfew was imposed, and a wave of arrests of those who participated in anti-government protests followed. By August 10, 2022, 3,310 persons were arrested.

Sri Lanka’s media faced serious challenges, as journalists were assaulted by police and military, subjected to teargas and water cannon attacks while reporting protests, and faced increased surveillance, threats and intimidation. The economic crisis along with the global increase in the price of paper pushed the print media to the edge, while more restrictions and surveillance were imposed on online spaces.

Ailing media industry

To respond to the economic crisis within the media industry, newspapers reduced the number of pages, hiked prices, and suspended certain editions. The chief operating officer of Liberty Publishers said that newsprint had already doubled in cost, from around USD 600-700 per metric tonne in 2021 to USD 1,200 per metric tonne as of March 2022. Upali Newspapers Ltd was forced to suspend publication of The Islander and the Sinhalese Divaina because of newsprint shortage. In May 2022, state-owned Associated Newspapers of Ceylon Limited (ANCL) stopped publishing five periodicals. In the same month, three weeklies published by ANCL went monthly. The suspension in August of imported paper, printing machines, spare parts, sound and video recording equipment including cameras, and transmission apparatus for broadcasting made the hard times harder, though the restriction on cameras and transmission apparatus was lifted in December 2022.

There was an unprecedented hike in travel costs. According to the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, transport costs increased by 117 per cent from February 2022 to January 2023. The serpentine queues outside gas stations reduced only in August 2022 when the QR code-enabled fuel pass system was introduced. Many journalists attempted to minimise travel and depended on online news gathering and reporting. Even this became difficult as Sri Lanka also experienced regular power cuts.

Low pay and job insecurity, regular issues faced by Sri Lankan journalists, were compounded by the crisis. A survey of 200 journalists conducted by the Free Media Movement (FMM) published in November 2022 found that 50 per cent of the respondents earned less than LKR 15,000 (USD 41) per month. Only 11 per cent of the respondents earned more than LKR 50,000 (USD 137). Provincial journalists who usually work for several media institutions are especially vulnerable to low pay and job insecurity. The survey also found that only 26 per cent of respondents had social security such as Employees Provident Fund or pension. While 74 per cent of the respondents expressed insecurity about their future, 53 per cent said that they were insecure about their profession. Significantly, 13 per cent said they were not allowed to join a trade union, as their institutions had banned it, despite such membership being a fundamental right guaranteed by the Sri Lankan constitution.

The Department of Government Information, under the Ministry of Mass Media, issues identity cards to local and foreign journalists. Despite being a long-term practice since 1984, it is not legally mandated to be registered at a government institution to work as a journalist in Sri Lanka, but government-issued media identity cards are often requested by the military, police or other security officials at government institutions.

Some government institutions including the Sri Lankan parliament only allow government registered journalists to cover events. The FMM survey found that only 55 per cent of journalists had the government-issued media identity card, while 61 per cent had an identity card from their institution, and 23 per cent did not possess any media identity cards, as a result of which entry to certain events – particularly those organised by the government — is prohibited. In many cases journalists were subjected to harassment by military and police, even after they present government-issued press IDs, so the absence of an ID makes them more vulnerable.

Media Rights Violations

Killings

Arrests

There is a growing realisation about how disinformation is adversely impacting the country’s socio-political milieu and contributing to political conflicts and media crises.

Demonstrators outside the United Nations’ Sri Lanka office protest against the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) in 2022. The PTA’s proposed replacement, the Anti-Terrorism Act, has been widely condemned as having the potential to exacerbate state repression and human rights abuses. Credit: Ishara S. Kodikara / AFP

Under attack

Safety and security continue to be a concern for Sri Lankan journalists. More than half, or 58 per cent of the journalists who participated in the FMM survey said they had faced safety and security concerns during their work. Significantly, 71 per cent of them said that they were not satisfied with the way their media institution had intervened in such issues.

Repression of Dissent, the periodical human rights situation update published by INFORM Human Rights Documentation Centre, recorded 36 incidents of rights violations relating to media and social media from May 2022 to January 2023, in which at least 50 individuals including 37 journalists and nine social media content creators were victimised. At least 21 were subjected to physical violence, while eight were arrested, and 12 were summoned or visited by police or military, while two others were obstructed and threatened by the military. While more than 50 per cent of the incidents were reported around the country’s capital city of Colombo, around 28 per cent of incidents were reported from the former war-affected North and Eastern provinces.

Journalists who covered anti-government protests and mob attacks faced repression. On the morning of July 22, 2022, when the military took over the Presidential Secretariat and surrounding areas occupied by the protesters, at least five journalists were assaulted. Despite showing his Press Identity and foreign accreditation cards, the military assaulted BBC Tamil’s journalist Jereen Samuel and his team. The officers repeatedly slapped Samuel, pushed him to the ground, and kicked him several times in the abdomen, and forcefully took his mobile phone and deleted the videos he was recording.

Ten journalists reporting on the arson attack on then Prime Minister Ranil Wickremasinghe’s private residence on July 9, 2022, were also assaulted by the police. Pradeep Sanjeewa Wickramasinghe, reporting for Derana TV, was hospitalised after experiencing breathing difficulties due to repeated tear gas attacks while reporting on protesters taking over the Presidential residence that day. In addition, around 10 journalists in the former war-affected North and Eastern provinces also faced assaults, threats, and being obstructed, questioned, summoned or visited by the police or military. Between May and November 2022, the government imposed a social media ban on public officers, preventing them from expressing their opinions. A medical officer who spoke to the media on child malnutrition was suspended.

On January 5, 2023, YouTuber Sepal Amarasinghe was arrested for allegedly insulting the sacred tooth relic of Kandy. Before his arrest, several politicians speaking in parliament condemned his statement and demanded that the government take action, while the chief prelates of the Temple of Tooth Relic also wrote to the president. Though it was initially said that he would be charged under section 3 of the ICCPR Act for allegedly advocating “national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence”, as with Shakthika Sathkumara who was arrested in 2019, Amarasinghe was released in February 2023 after an unconditional apology.

In October 2022, the United Nations Human Rights Council adopted a resolution on promoting reconciliation, accountability and human rights in Sri Lanka (A/HRC/51/L.1/Rev.1). Sri Lanka’s Foreign Minister Ali Sabry stated that Sri Lanka categorically rejects the resolution, as it was allegedly presented without Sri Lanka’s consent, despite the efforts to engage with the main sponsors. The resolution expressed concern on the human rights impact of the economic crisis, and other developments since April 2022, including violence against peaceful protesters, and called for independent investigations into all the attacks. It also stressed the importance of protecting civilian government functions from militarisation, and ensuring independence of judiciary and key institutions, and addressing incidents of intimidation and harassment of journalists among a range of other issues.

Too few women

The percentage of female journalists in Sri Lanka is only 15 per cent of the total 5,936 journalists registered with the Department of Government Information. When it comes to provincial journalists, only 2.3 per cent are female. However, a recent survey conducted by the FMM has reported a relatively better picture. The survey found that around 25 per cent of female journalists were employed in Sinhala and Tamil language media, while 43 per cent of women journalists work in the English language media.

One of the reasons for the discrepancy in the data could be the difficulties faced by digital journalists in obtaining government registration and press IDs, while FMM has included digital journalists in its survey. Secondly, it is also possible that women journalists might not have obtained the government registration, especially if they only do desk work.

Low participation of women in the labour force is a general trend in Sri Lanka, with the national female labour force participation rate reported at 32 per cent, despite high levels of female education. Gender disparity becomes more obvious at senior level positions, as fewer women get to such positions. Many women journalists had spoken out about sexual harassment in newsrooms in a belated #MeToo movement in 2021. However, no investigations were conducted.

A popular television journalist at the state-run Independent Television Network was forced to resign due to undue sexual invitations and harassment from ‘elderly heads’ of the institute.

Sri Lankan women and the LGBTIQ+ community routinely experience online abuse, harassment and sexism. The incidence of sexual harassment in the workplace is higher in the Sinhala and Tamil language media as compared to the English Language media. The number of women who use social media is also low compared to men. This may be because they face more online harassment. A study conducted in 2022 by the Hashtag generation, an online movement in Sri Lanka, found that Muslim women and transgender persons are more vulnerable to digital threats.

When the military took over the Presidential Secretariat and surrounding areas occupied by the protesters, at least five journalists were assaulted.

A television in Sri Lanka shows colour bars after broadcaster Rupavihini was taken off the air in July 2022, after the state-run news outlet interviewed two protestors live on air. Widespread protests and the resulting government crackdown on dissent defined challenges to Press Freedom in Sri Lanka in 2022-23. Credit: Twitter

Digital divide

There are 14.58 million internet users in Sri Lanka, equal to 67 per cent of the Sri Lankan population, but there are wide disparities in usage. Though the start of the Covid19 pandemic saw a sharp increase in the number of internet users, by 2022 it was in step with the growth of population. Of the 7.2 million social media users in Sri Lanka; only 37.3 per cent are female. This gap can be attributed to gender-based violence, discrimination and misogyny, both online and offline. Facebook and YouTube are the most popular social media platforms, contributing to 76 per cent and 13 per cent social media web traffic each.

In 2022, Tharindu Jayawardena, a media rights activist and the chief editor of MediaLK website, made a complaint to the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka (HRCSL), saying that his fundamental right to freedom of expression, including freedom of publication, had been violated. He described the difficulties he faced while registering his website with the Department of Government Information, on the ground that the website was allegedly a “risk to national security”.

Though the registration of news websites is not mandatory, the Department of Government Information has been registering news websites since 2011, and government media identity cards are only issued to journalists working with registered websites. According to Jayawardena, digital journalists are treated differently during the registration process and issued with only one or two media identity cards per website, while no such limit is imposed on legacy media institutions.

Following the inquiry, the HRCSL concluded that the Ministry of Mass Media had violated the fundamental rights of the journalist and recommended that the Ministry introduce a more transparent, collaborative and lawful mechanism to register the websites, with the collaboration of all the relevant stakeholders.

Social media platforms including Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, Viber and YouTube were temporarily restricted during anti-government protests on April 3, 2022. In July 2022, anti-government protesters at multiple times experienced internet and mobile signal jamming around the protest site in Colombo. This was especially noticeable when protesters took over the Presidential Secretariat and the President’s House in Colombo.

In January 2023, President Ranil Wickremesinghe said that a new bill would be introduced to regulate social media and electronic media, similar to Singapore’s Info-communications Media Development Authority (IMDA) Act 2016 and regulatory framework based on Singapore’s Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA). Human rights reports indicate that both POFMA and IMDA in Singapore have been used to silence dissent and restrict freedom of expression and must be viewed with concern.

IFJ and the FMM of Sri Lanka jointly issued a statement condemning the Circular dated September 27, 2022, issued by the Ministry of Public Administration restricting government servants from expressing their opinions on social media and warning that disciplinary action would be taken against errant public officers. In October 2022, a medical doctor, Chamal Sanjeewa, who spoke to the media about the alarming rates of child malnutrition in a village in Hambantota district, based on a study he had conducted, was suspended for violating the establishment code for public officers.

Earlier, in March 2022, Parami Nileptha Ranasinghe, a freelance female television presenter with Sri Lanka Rupavahini Corporation (SLRC) for 15 years, was banned from SLRC after her Facebook post critical of the administration. In April 2022, Anuruddha Bandara, a social media activist, and an admin of the GotaGoHome Facebook page, was arrested for allegedly “exciting or attempting to excite disaffection to the President or Government in Sri Lanka,” a colonial law that originally sought to restrict criticising the queen and her colonial government. Arrested by Colombo police at his home in Gampaha, more than 100 km from Colombo, Bandara’s whereabouts were unknown for around a day, until the National Human Rights Commission intervened and the police confirmed that he had been arrested. He was granted bail and released in June 2022 He filed a fundamental rights petition in April 2022 against the state for violating his freedom of expression and right to equality before law, for which leave to proceed was granted in January 2023.

In June 2022, journalist and former president of Sri Lanka Young Journalist Association (SLYJA), Tharindu Uduwaragedara, was summoned to appear before the Sri Lanka Computer Crimes Division of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) of Police in Colombo following a complaint made by the intelligence unit of Sri Lanka Air Force for alleged “contradictions between the headings and the content in his videos” published on his YouTube Channel.

In November 2022, Uduwaragedara and the current president of SLYJA, Tharindu Iranga Jayawardana, were summoned and interrogated by the CID for publishing a Facebook post seeking public support to identify the police officers who had assaulted the participants of an event held in October 2022 at Galle Face Green to remember those lost during the anti-government protests.

Digital journalists are treated differently during the registration process and issued with only one or two media identity cards per website, while no such limit is imposed on legacy media institutions.

SLWJA members, and Sri Lankan human rights activist Sandya Ekneligoda, commemorate Black January on January 27 in Colombo, remembering the journalists and civil society actors who have been killed, assaulted or disappeared in Januarys past. Despite international pressure, killers of journalists often escape with impunity, with some cases spanning decades without substantial or definitive police investigations. Credit: SLWJA

Justice for Slain Colleagues: The Legal Saga

The murder of Lasantha Wickrematunge and the enforced disappearance of Prageeth Ekneligoda are two emblematic cases that remain judicially unresolved despite strong evidence to suggest the involvement of the Sri Lankan military and political leaders of the time. Both cases are still pending in the courts, more than a decade on.

Lasantha Wickrematunge case: The case of senior journalist Lasantha Wickrematunge who was murdered in January 2009 was heard at the People’s Tribunal in Hague on May 12-13, 2022. The tribunal found the Government of Sri Lanka responsible for grave violations of rights of Lasantha Wickrematunge, more specifically violating the right to life, the right to freedom of expression, and the right to an effective remedy. Witness testimonies were provided by activist Sandya Ekneligoda, the wife of disappeared journalist Prageeth Ekneligoda; by journalist Dilrukshi Handunnetti; by the exiled investigator and former Inspector of Police Nishantha De Silva, who had conducted investigations into the murder of Lasantha Wickrematunge; and by several other experts including a civil society activist and an exiled journalist. De Silva in his testimony presented a detailed analysis on the findings of the investigations that were conducted, and how a military intelligence unit named Tripoli Platoon carried out multiple attacks on journalists in Sri Lanka’s post-war period.

Prageeth Ekneligoda case: Journalist Prageeth Ekneligoda was reported missing since January 24, 2010, after allegedly being abducted by the Sri Lankan military. The nine military officers charged with abducting and murdering Prageeth Ekneligoda were granted bail on June 17, 2022. On March 1, 2023, the court again postponed the hearing of the case to May 4, as the prosecutor requested more time to tabulate analysed reports of mobile phone communication details of two suspects.

On November 3, 2022, Sandya Ekneligoda had written to the Chief Justice, saying that entry into the court premises had been barred for civilians after the Covid19 outbreak. She requested that the chief justice allow the public to attend the court hearings.

When the fundamental rights petition filed by Sandya Ekneligoda against the Political Victimization Commission was taken up for hearing on October 25, it was scheduled for further hearing on November 18. However, in February 2023, the cabinet stated that it would not implement the recommendation of the said commission. The commission report that was handed over to the President in 2020 included many problematic recommendations including the acquittal of suspects in several emblematic cases, including that of Prageeth Ekneligoda.

Caricatures of former Sri Lankan prime minister Mahinda Rajapaksa are displayed at the Galle Face protest area near the Presidential Secretariat in Colombo on July 17, 2022. The country’s economic and social turmoil brought significant challenges to human rights, freedom of expression and the media industry across the island. Credit: Arun Sankar / AFP

July attack on journalists

The Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka (HRCSL) conducted an inquiry into the attack on a group of Sirasa TV journalists, who were reporting the entry of protesters into then Prime Minister Ranil Wickremasinghe’s private residence in Colombo on July 9, 2022. HRCSL summoned the Commandant of the Special Task Force (STF) of Police, DIG Waruna Jayasundera, and Director STF, SSP Romesh Liyanage, and SSP DS Wickremasinghe of the Special Investigation Unit (SIU) of Police for the inquiry.

Despite video evidence of the assault on media personnel by the STF, Liyanage denied any knowledge of the assault, and even denied his presence during the assault. HRCSL in a public statement said they had serious doubts regarding the credibility of the evidence given by SSP Liyanage and concluded that he was unequivocally responsible for the attack on media personnel. Subsequently, SSP Liyanage was suspended on July 11, 2022, for allegedly assaulting the Sirasa TV journalists. Ten days later, he was reinstated after he was found not guilty based on a confidential, internal inquiry conducted by the SIU of the police.

The legal environment

Emergency was declared in Sri Lanka in April, May and July 2022, during the anti-government protests. At least 10 orders declaring curfew were issued during the state of emergency period, which also saw the armed forces being called out. In September 2022, Sri Lanka declared eight high security zones, under the Official Secrets Act, covering a long list of key government buildings and surrounding areas including public roads, which were closed to public gatherings and processions in an attempt to prevent a repeat of the protests. On September 27, HRCSL issued a press statement saying that the declaration of high security zones grossly violates the fundamental rights of the people and noted that the Official Secrets Act cannot be adopted to declare High Security Zones. The chief opposition party filed a fundamental rights petition against the gazette, and civil society organisations held that it was illegal. Following this pushback, the gazette was revoked on October 1.

The state of emergency, curfews, and increased powers granted to the military and the declaration of high security zones resulted in restricting the exercise of rights and increasing challenges for journalists, protesters and the public. Large teams of riot police and military were deployed to prevent protests, while court orders often prevented protesters from entering certain roads or areas.

At the same time, the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) was used to arrest protesters and activists in 2022. The PTA has been used for more than four decades to arrest and detain journalists, civil society activists, protesters, and other dissenters, enabling prolonged arbitrary detention, extracting false confessions through torture, and targeting minority communities and civil society groups. The amendments to the Act in January 2022 were grossly inadequate and failed to address critical gaps, including problems in the definition of terrorism, admissibility of confessions, the 72-hour detention period before production before a magistrate, the lack of judicial oversight during investigations, legal representation, informing the cause of arrest when arresting etc. The amendments seemed tokenistic, and an attempt to address international pressure, rather than a genuine willingness to overcome long existing issues.

On September 6, 2022, 13 detainees held under the draconian PTA began a hunger strike demanding their release. An island-wide signature campaign demanding the repeal of PTA was launched by a group of civil society organisations, trade unions, and the youth wing of a Tamil political party, and received wide support. Alongside, university students also conducted protests. On January 16, seven international organisations issued a letter demanding the release of student activist Wasantha Mudalige, who had been detained for 150 days under the PTA. On January 30, 2023, over 12,000 affidavits requesting the release of student activist Mudalige were handed over to the Department of Attorney General. A day later, the PTA charges against Mudalige were dropped.

According to the annual report of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR) published in October 2022, 47 persons remained in long-term detention under PTA. Of these, 22 are serving sentences and 25 are at various stages of appeal. They also noted that large numbers were detained after the Easter Sunday Bombings in 2019. While the police have often been reluctant to release information on PTA detainees, the RTI commission recently instructed the police to provide details on PTA detainees to a lawyer who made a RTI request. In August 2022, Sri Lanka delisted six organisations and 316 individuals listed under counter-terrorism regulations, while three organisations and 55 individuals were added to the list. This included the poet Ahnaf Jazeem who was detained for 18 months under the PTA and released on bail in December 2021.

The government proposes to introduce a new Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA) to replace the PTA, and other draft laws to regulate cybersecurity, including an online safety bill to “combat online falsehood and manipulation”. Civil society groups and media rights groups have not been consulted. Attempts by previous governments to introduce such laws have often been met with strong criticism and suspicion from media rights groups and rights activists, as such laws with vague definitions and sweeping powers, are likely to introduce new restrictions and regulations on freedom of expression and other fundamental freedoms.

Since its enactment in 2017, Sri Lanka’s Right to Information Act has allowed journalists to access verified information from official agencies. However, the path has not always been smooth. The court of appeal, in a landmark judgment ordered the release of information on Members of Parliament who have submitted asset declarations, based on a Right to Information request made by a journalist in June 2018. After Parliament officials denied the request, the applicant journalist Chamara Sampath appealed to the Right to Information (RTI) Commission. The RTI commission ordered Parliament officials to release the relevant information in February 2021. However, the Secretary General of Parliament appealed against the order. In March 2023, almost five years after the request was first made, the Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal made by the Secretary General of Parliament and affirmed the previous order issued by the RTI Commission, allowing the release of the requested information.

Curbing disinformation

Currently there is no law that tackles fake news and misinformation. However, arrests are made under penal code provisions and PTA.

During a meeting with media heads in Sri Lanka on March 6, 2023, President Ranil Wickramasinghe stated that the government was working to introduce new laws to regulate social media, similar to Singapore’s. This, as discussed above, has been met with strong misgivings by civil society and media.

On April 19, 2021, the cabinet of ministers approved a joint proposal by the then Minister of Justice and Minister of Mass Media to draft a Bill to regulate online falsehoods. In March 2023, a group of activists, including some journalists, issued a letter in response to the President’s statement, and noted that they are concerned whether the move might be used to advance ongoing efforts of surveillance and curtail the freedom of expression in the country.

There is a growing realisation about how disinformation is adversely impacting the country’s socio-political milieu and contributing to political conflicts and media crises.

Lawyers hold signs at a protest against Sri Lanka’s Prevention of Terrorism Act in Colombo on September 23, 2022. The PTA has been used to silence dissent for over four decades, with broad ‘terrorist’ definitions allowing the state to proscript organisations, extract false confessions, and enable arbitrary detentions, all of which often target minority groups and civil society organisations. Credit: Ishara S. Kodikara / AFP

Small is vulnerable

A significant number of journalists working in smaller media organisations, running websites or YouTube channels, were subjected to increased threats, intimidation and assaults. On July 22, three journalists working for Xposure News website were assaulted and tortured when reporting a military raid on protesters in the main protest site in Colombo. Five days later, their office was visited by police in civilian clothing, asking them to identify some photos and give access to their CCTV footage. They left the premises after monitoring the entrance of the premises for around an hour.

Several journalists working for the Tamil Guardian website that covers regional news in the North and East were subjected to threats and intimidation as in previous years. Three YouTubers were summoned and questioned by the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) of the police on the content of their channels. One YouTuber was arrested for allegedly insulting the temple of the tooth relic in Kandy. Another YouTuber Rathindu Senaratne was questioned multiple times and arrested for taking part in protests. Media activists said that the Department of Government Information has refused to issue press identity cards to journalists running news YouTube channels. Shortages of paper and materials have made it almost impossible for hyperlocal media to use the print media.

Collective resistance

Responding to the economic and political crisis has also shown the need to build professional capacity in the media. Providing more training and other opportunities, including trade union leadership, for women and young journalists is essential to build gender and youth inclusive media workplaces. It is also important that media institutions have effective workplace policies to address gender-based violence and sexual harassment. Existing difficulties with media identity cards, news website registrations, and surveillance on journalists must be addressed, with policy actions taken to ensure safety and protection of journalists while addressing specific challenges faced by youth, digital journalists, and provincial journalists.

Lack of formal training and physical danger are just some of the downsides in this field. From the data gathered by the Federation of Media Employees’ Trade Unions (FMETU), it is evident that journalists in Sri Lanka are grappling with myriad challenges with little prospects for the future, whilst they report from the ground. There is concern that these problems may tempt vulnerable journalists to indulge in unethical practices, compromising on ethical journalism.

The period under review saw civil society and the media struggling to rise after a battering by the economic crisis and a government-declared Emergency. Journalists and media rights activists in Batticaloa and Colombo participated in the annual Black January event demanding justice for journalists who were murdered, forcibly disappeared, assaulted, or threatened in Sri Lanka. The FMM organised an event in Colombo under the theme ‘Moving Forward Together to Save Media Professionals,’ which included a candlelight vigil, a panel discussion by a group of journalists, and a speech on press freedom delivered by a former President of the Bar Association. Separately, Sri Lanka Working Journalists Association (SLWJA) also organised a protest and a candlelight vigil in Colombo. The Union of Professional People’s Journalists of Sri Lanka and the Eastern Mridhya Samaj jointly organised a protest and a candlelight vigil in Batticaloa.

Despite being subjected to frequent assaults, repression and shortages, pay cuts, curbs on information gathering, and online abuse, faith in the power of resistance was evergreen.