PAKISTAN

Broken Promises

Supporters gather around a car carrying former Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan as he arrives to appear before the high court for a protective bail in relation to two cases, in Lahore on March 21, 2023. After the former Prime Minister was ousted in 2022, the polarisation of Pakistani politics has been a key driver of violations against media. Credit: Arif Ali / AFP

The situation of media freedom in Pakistan is one of extreme concern. It has continued to deteriorate over the past few years and the change in government in 2022 did not provide the respite many had hoped it would.

In the period under review, over 90 separate cases of violations were recorded – murders, physical attacks, kidnappings, illegal detentions, aggressive harassment, intimidations, legal cases, bans and censorship. At least 75 journalists were the victims. Women and transgender journalists were among the media practitioners who bore the brunt. Independent media houses, digital journalism platforms, and social media giants all came in the crosshairs of a host of threat actors ranging from state actors, political parties, parliament, businesses, criminal gangs, and other intimidators. The numbers of actions and attacks increased, as did the impunity for crimes against journalists.

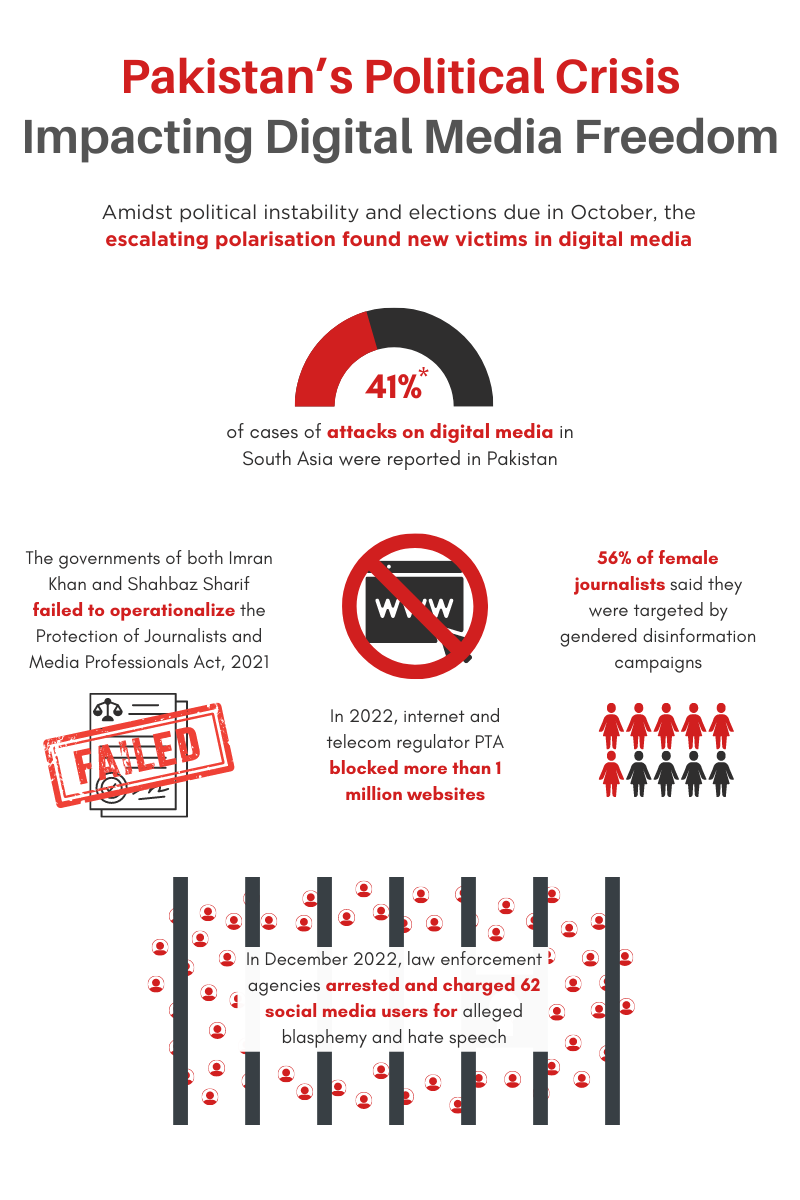

A key driver of violations against media was an escalating polarisation in politics, especially after former prime minister Imran Khan was ousted in 2022 by the incumbent ruling coalition. The growing criticism of the military establishment by Khan and the angry reactions against him were messy. There were bans, gag orders and censorship galore, with the most vocal political critics (politicians such as Imran Khan, Azam Swati, Shahbaz Gill and Fawad Chaudhry) and media critics (journalists Arshad Sharif, Sami Ibrahim, Sabir Shakir and Imran Riaz) of the military finding themselves charged with sedition, blasphemy and defamation. Being a politician or a party worker critical of the military often meant being banned from the media. The signature case related to attacks on media was that of Arshad Sharif whose assassination in 2022 in Kenya under mysterious circumstances shocked the country.

There were other key hits and misses. The big miss was the opportunity to build on Pakistan’s progressive act of becoming the first country in Asia to have legislated on guarantees of safety of journalists. The governments of both Imran Khan and Shahbaz Sharif failed in 2022 to operationalise the federal Protection of Journalists and Media Professionals Act, 2021. Despite a promise before an international conference in Islamabad in December 2022 on the safety of journalists, Prime Minister Sharif has failed to notify the safety commission under the law to start delivering safety and justice to journalists. The one bright spot was that a separate law, the Sindh Protection of Journalists and Other Media Practitioners Act, passed by the government of Bilawal Bhutto’s PPP party in 2021 was operationalised in 2022, instituting a safety commission that has started meetings to extend assistance to journalists in Sindh.

Precarious transition

In the period under review, the health of the media industry in Pakistan continued to decline with a distinct shift in audiences from broadcast media – television and radio – to internet-based media. Both legacy media (print and electronic) and digital-only independent journalism platforms became a distinct sub-section of the digital media landscape. This has had consequences – shrinking of state and corporate sector advertising budgets for print and broadcast publications have led to a shrinking media economy with consequent job losses. While accurate data is difficult to come by, job losses for journalists and other media workers, non-payment of salaries, and wage cuts continued in the period under review, though the situation was an improvement from the previous year. The situation was exacerbated by a near economic meltdown in Pakistan, partly arising from a seemingly intractable political crisis.

While the shrinking of the formal media sector in Pakistan is partly due to a drastic squeeze on public sector advertising, the growth in online and social media has forced media organisations to adjust to alternative models that are changing news output, revenue generation, audience consumption, and employment volumes.

The biggest casualties are in the number of journalists and media workers. The former have shrunk by an estimated 45 per cent; from 20,000 three years ago to around 11,000 in 2023. With most news workers worried about keeping their jobs, there is widespread job uncertainty in Pakistani journalism. A number of journalists have shifted to social media sites like YouTube to carry on their journalism.

Media Rights Violations

Killings

Arrests

Camels walk down a road in Mehar city after heavy monsoon rains in Dadu district, Sindh province, on September 9, 2022. The past year has seen much change in Pakistan, and many industries, including the media, have faced significant challenges amid socio-political and environmental challenges. Credit: Aamir Qureshi / AFP

Bearing the brunt

In the period under review, at least 93 separate cases of violations were recorded against at least 75 journalists, including against at least five women and transgender journalists, and against several media establishments. These included the killing of five journalists; 19 attacks resulting in injuries against 26 journalists; five attacks against seven journalists; six incidents of threats against as many journalists; seven incidents of kidnapping of as many journalists; six arrests; four detainments without charges; 11 separate legal actions against 17 journalists and at least 16 instances in which 26 journalists were aggressively intimidated and stopped from their duties. In addition, two media establishments faced hostile actions and a blanket ban was placed by parliament against all journalists who operate on social media, such as YouTubers.

Also documented were at least 11 separate instances of action against media houses and social media platforms by the electronic and internet media regulators. In December 2022, Pakistani journalists and rights activists called for an urgent need to check organised trolling, which was gaining ground in the absence of effective laws to check the practice.

Another key highlight was the government proclivity to register cases against journalists for free speech. In one instance alone, in May 2022, authorities registered multiple cases against several journalists including Arshad Sharif (who was later murdered in Kenya), Sabir Shakir, Sami Ibrahim and Imran Riaz Khan – all military critics and close to Imran Khan – for allegedly posting ‘anti-state’ comments.

On the positive side, the Sindh provincial government officially notified the formation of a special commission for the protection of journalists in December 2022. This raised hopes that journalists in Sindh could finally use the law to file complaints about threats to their safety. Media rights watchdog Freedom Network and the Sindh chapter of the Pakistan Journalist Safety Coalition plan to work with the commission in 2023 to build its capacity to reduce the impunity for crimes against journalists. Additionally, Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif promised journalists in a tweet that his government would “fully implement” the federal law for the protection of journalists. Passed in late 2021, it has not been enforced.

Personal security concerns were fore fronted during trainings on journalist safety conducted by the IFJ in several press clubs across the country over the year.

The writ filed by PFUJ Secretary General Rana Muhammad Azeem to review laws relating to journalists pertaining to job security, irregular wages, personal security, illegal terminations etc. continues to be heard in the Islamabad High Court.

No place for women

In the period under review, there was little to cheer about the status of women in Pakistani media and prospects of an enabling environment remained distant. In October 2022, Sadaf Naeem, reporter of Channel 5 News, was killed while covering the political rally of former prime minister Imran Khan in Punjab. She was crushed under the truck carrying Khan while trying to climb up for a live report. Naeem’s death highlights the need for safety training and should serve as a wake-up call for the media, political parties, and officials on the arrangements needed to ensure the safety of journalists on the field.

Days later Khan made widely censured remarks about journalist Gharida Farooqi saying she should “expect to be harassed online” as she was working in a “male-dominated” environment and had “forced her way into male-dominated spaces”. Khan made the remarks when questioned at a meeting by journalists about the rampant harassment of female journalists at his party PTI’s rallies. In recent years, PTI supporters have been involved in an increasing number of harassment and assault incidents against women journalists.

In May 2022, two Samaa TV media practitioners were attacked while covering a PTI rally. TV reporter Zamzam Saeed had her clothes ripped, while her cameraperson Imran Khan was attacked with rocks and had his equipment broken. Senior journalist Asma Sherazi was the victim of online harassment and trolling by PTI and its social media team after she published an article for BBC Urdu. In 2023, a group of 30 men at a PTI rally attacked and sexually harassed prominent journalist Quatrina Hosain and her team in Wah, Punjab, leaving one person hurt and equipment destroyed. Anchors and reporters Sana Mirza and Maria Memon were attacked while covering a PTI gathering. Both incidents were captured on video, with PTI supporters seen hurling missiles and shouting abuse.

A study in January 2023 by non-profit media literacy organisation Media Matters examined key challenges for women in Pakistani media spaces, including labour rights and dealing with a stubborn glass ceiling, and why many of them have recently been quitting their careers. It found that of the over 100 women journalists surveyed only 3 per cent were able to reach leadership roles; more than 60 per cent did not get annual pay raises; 89 per cent said their male counterparts got better salaries for the same work; 88 per cent said there were no equal opportunities for career growth; 82 per cent said women journalists faced gender discrimination; 69 per cent said the lack of women decision makers compounded discrimination in newsrooms; 33 per cent said there was no gender inclusion policy in their newsrooms; 56 per cent reported having faced workplace harassment; 68 per cent said they were not members of any press club body while 62 per cent did not belong to any journalists’ union.

A report of mapping of gender disparity in the media in 2022 by Islamabad-based NGO Individualland with the support of International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) found that gender discrimination in the media began at the time of recruitment itself. As many as 75 per cent of the respondents said that women faced difficulty in getting jobs in the media. As for wage equality, 35 per cent said there was a gender-pay gap, despite laws against discrimination. About 43 per cent reported having faced sexual harassment at the workplace. A woman journalist quoted in the study said that a male colleague had slapped her, saying; “My honour does not allow a girl to work among men without covering her head”. The photojournalist was only given a formal warning, but no action was taken against him, pointing once more to the lack of redress or a will to create a conducive workplace for women.

The launch in December 2022 of the Women’s Media Forum, Pakistan (WMFP) comprising women leaders in media organisations, unions and press clubs, was an outcome of consistent mentoring and gender mapping by IFJ partners in the country. The WFMP aims to be dynamic, diverse and representative network of women in media to act as an advocacy group to raise concerns of gender inequity in the media and seek resolution from relevant institutions.

In May 2022, authorities registered multiple cases against several journalists including Arshad Sharif (who was later murdered in Kenya), Sabir Shakir, Sami Ibrahim and Imran Riaz Khan – all military critics and close to Imran Khan – for allegedly posting ‘anti-state’ comments.

Women wait for food aid from the Pakistani government during Ramadan in Peshawar on March 29. Women in media faced harassment, discrimination, online abuse, and one death while on the job. Credit: Abdul Majeed / AFP

Shadow of extremism

Right-wing extremism in Pakistan has had a serious impact on media’s ability to report freely, especially when it comes to blasphemy issues. Extremists have used threats and attacks to intimidate and silence journalists, as well as to pressure media outlets into censoring content related to blasphemy. In recent years these threats have resulted in self-censorship and the widespread under-reporting of blasphemy issues leading to a chilling effect on the press. This has majorly impacted the freedom of expression and resulted, in general, in a decrease in the diversity and quality of reporting.

Some of the most notable cases of media-related right-wing extremism include the murder of journalist Saleem Shahzad in 2011, the assassination of prominent human rights activist Sabeen Mahmud in 2015, and the kidnapping of journalist Zeenat Shahzadi in 2015. In 2016, journalist Shama Junejo was attacked and threatened with death for her coverage of blasphemy cases. In the same year, journalist Taha Siddiqui was attacked and threatened with death for reporting on religious minorities. In 2018, prominent journalist Gul Bukhari was abducted in Lahore on her way to the Waqt TV studio and released after pressure from human rights groups.

In August 2022, journalist Waqar Satti was booked under the blasphemy law for allegedly defaming Islam by reporting remarks ascribed to former prime minister Imran Khan. He was later exonerated after a vigorous campaign by the PFUJ, which was also supported by civil rights groups. In February 2023, journalist Sabookh Syed, the president of Pakistan Digital Media Alliance, faced death threats and was hounded on Twitter by Islamist party Tehrik Labaik Pakistan for defending the rights of religious minorities.

In December 2022, law enforcement agencies arrested and charged 62 social media users with posting ‘blasphemous’ material and propagating alleged hate speech. Of the arrested, nine were initially awarded capital punishment by trial courts and two by high courts. In May 2022, the Federal Investigation Authority arrested two people in Lahore for uploading and sharing blasphemous content on their social media accounts. In May 2022, the Islamabad High Court ordered the Ministry of Information Technology and internet regulator Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) to take measures against blasphemous tweets by Scandinavian politician Geert Wilders to ‘protect the religious emotions of Muslims’.

Controlling the airwaves

The Pakistan government’s obsession with controlling free speech and access to plural sources of information continued in the period under review. Various contentious regulations continued to be used to curb free expression, as did attempts to introduce a new regulatory framework.

In February 2023 reports emerged of the federal cabinet mulling new legislation amounting to a crackdown on social media activists involved in “defaming the armed forces and judiciary”. The cabinet eventually backed off after a split in opinion and agreed that existing laws should be invoked rather than bringing a new bill. In May 2022, the Islamabad High Court thwarted an attempt to bring in social media rules that impinged on civil liberties.

Other attempts at curbing free speech continued. Internet and telecom regulator PTA said in January 2023 that it had blocked more than one million websites in 2022 alone. This is in addition to the fact that Pakistan has in the past few years figured among the top five requesters to Twitter and Facebook for content removal. In October 2022, TikTok said it had removed more than 15 million videos posted from Pakistan.

In May 2022, the Lahore High Court warned Imran Khan’s party PTI to desist from uploading videos and opinion critical of the judiciary. In the same month, the government of Sindh province ordered a scrutiny of social media users who are overtly critical of state institutions. In October 2022, there was outrage after it appeared that federal investigation agencies had compiled a list of 814 national and international social media activists, including journalists and bloggers, engaged in “propagating against state institutions, political governments and sensitive personalities.”

In October 2022, internet regulator PTA issued a notice requiring all VPN users to register with the authorities or risk punitive action. In September 2022, PTA intermittently blacked out YouTube services to prevent Imran Khan’s party followers from circulating videos critical of the government, military and judiciary.

In November 2022, the website of FactFocus, known for its investigative journalism, was censored after a report detailing alleged corruption by army chief General Qamar Bajwa.

In January 2023, the secretariat of the National Assembly banned the entry of YouTubers, TikTokers and other social media influencers into parliament to cover proceedings or talk to parliamentarians.

The 2022 State of Digital Journalism report, produced by the Institute for Research, Advocacy and Development (IRADA), examining the state of digital journalism in Pakistan over the past one year, revealed that independent online journalism in Pakistan faces a host of challenges including financial issues, safety risks and disinformation campaigns. It said Pakistani digital news outlets were fighting an existential battle due to lack of resources, financial insecurity, and safety risks but, at the same time, they were also exploring avenues of audience development, factchecking, and social media monetisation to win the trust of online audiences and ensure viability for their operations.

In February 2023, acting on court orders, PTA asked Wikipedia to remove some content alleged to be blasphemous and then banned it altogether. The platform was restored two days later after a public outcry.

There were also some affirmative policy actions and positive developments in the period under review for independent digital media and internet-based journalists in Pakistan. In August 2022, Pakistan successfully trialled one terabit per second internet speed and three months later, Punjab became the first Pakistani province to achieve Web 3.0 status. The same month the government announced that Pakistan would launch 5G services in 2023. Also in November 2022, Google reported that Pakistan was one of its fastest growing global markets and announced that it would be opening an in-country office.

There is a growing realisation about how disinformation is adversely impacting the country’s socio-political milieu and contributing to political conflicts and media crises.

Supporters of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf leader and former Prime Minister Imran Khan gather outside his house after he was deposed through a parliamentary non-confidence motion on May 8, 2022. Political polarisation has directly endangered journalists and press freedom, resulting in the censorship of news outlets, harassment and arrests. Credit: AFP

Death of justice

The impunity for crimes against media practitioners continued. The mysterious and brutal murder of senior journalist Arshad Sharif embroiled the parliament, the judiciary and the military.

Shot dead on October 23, 2022, while driving to Nairobi in Kenya, there has been no clarity on what really happened, who was to blame, and how his family can get justice. While initial accounts from Kenyan police appeared to show that Arshad was fatally shot when allegedly refusing to stop at a security roadblock, a whisper campaign insinuated that since he was a sharp critic of both the Shahbaz Sharif (no relation of Arshad) government and army chief General Qamar Bajwa, either could have been allegedly involved in his assassination. Both the military and the government rubbished the claims.

The government-established investigation committee was rejected by Arshad’s family. Ultimately the Supreme Court took suo moto action and established an investigation team that has since produced two progress reports, including one in March 2023, but which has drawn a blank on both the motive and identity of Arshad’s assassins. In November 2022, on the eve of a nationwide protest by PFUJ against Arshad’s killing, the IFJ noted, “Transparent and thorough investigations into crimes against journalists are unfortunately rare in Pakistan. The IFJ urges the authorities in Pakistan and Kenya to complete an immediate and thorough investigation into Arshad Sharif’s murder, so impunity is not permitted to run rife for this crime.”

The Freedom Network’s Annual Impunity 2022 report released in November revealed that 53 Pakistani journalists were killed between 2012 and 2022 but the perpetrators were convicted in only two of these cases.

The report states that “due to poor investigation, the police fail to produce charge sheets in many cases, killing the chances of justice at an early stage of the legal system” and “due to the poor quality of prosecution, most cases never complete the trial process in the courts”.

The data showed that around one in every five murdered journalists failed to get justice because police apparently did not complete investigations, which prevented the cases from going to trial. Less than half the murder cases reached the court and were declared fit for trial, which indicates that for every second journalist murdered, the race for justice ends at this early stage. For nearly all journalists murdered (51, or 96 per cent), either First Information Reports (FIRs) were not registered, police investigations were not completed, cases were not fit for trial, trials not completed, or alleged killers were not convicted or punished.

In a major indictment of media employers as well as an indication of the state of the rights of media workers, the same report reveals that in over two-thirds of the cases, the process of invoking the legal system was left to bereaved families, making the matter of seeking justice a private family affair. The media organisations or employers, on whose behalf the journalists had taken on safety risks, were not party to the process of getting justice for their killed employees.

Judicial reprieves

In March 2023, the Islamabad High Court, hearing a petition seeking protection of and legislation on the rights of journalists and media workers filed by several media stakeholders, including the IFJ, ordered the government to form a five-member committee to drive the process. The committee includes ministers and secretaries of the federal ministries for law and justice, and information and broadcasting, as well as senior anchor Hamid Mir representing the petitioners. The order came after the court was informed by the government and the petitioners that they had produced separate legislative drafts. The court said a final single draft should be produced in consultation between the two sides.

In 2022, the Islamabad High Court struck down a controversial ordinance that had extended the scope of online defamation and increased the prison term for this offence. The court also struck down the criminal offence and punishment clause for online defamation (Section 20) from the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act (PECA) 2016. The court order was a big win for press freedom and freedom of expression in Pakistan. There have been civil society campaigns to repeal the ordinance and remove the criminal defamation clause from PECA.

The Federal Investigation Agency appealed the High Court’s decision in the Supreme Court but withdrew the appeal after civil society stakeholders protested strongly. Subsequently, the FIA closed 7,000 cases related to criminal defamation under the now-defunct PECA Section 20. In July 2022, a study outlined in detail the history of the Pakistani state’s efforts in recent years to criminalise defamation and erode media freedoms.

In another significant ruling, the Lahore High Court on March 30, 2023 struck down the colonial era Section 124-A of the Pakistan Penal Code, more commonly known as the “sedition law”. This was widely hailed as a major step towards loosening the state’s grip on the freedom of expression. In the period under review, several opposition politicians and media practitioners were charged under Section 124-A for alleged treason, which carries jail terms and fines.

A new report commissioned by PFUJ, “An analysis of legal framework for media workers in Pakistan”, provided proposals and suggestions for reforms in legislation. With an overview of laws regulating the rights of women working in media in Pakistan, the report offers suggestions for changing legislation to enhance the rights and facilities of media employees, with an emphasis on female media workers. The report also fed into an advocacy effort to lobby with political leaders, media houses and ministries.

New face of media

In the past few years Pakistan’s media landscape has been transforming in line with global trends, where an ecosystem of independent digital media start-ups has become the face of ‘new journalism’ in the country. This is characterised by a focus on public interest journalism and taking up community issues that the legacy mainstream media has almost given up under corporate and state pressure. This hyperlocal sub-sector of the media is represented in the Digital Media Alliance of Pakistan (DigiMAP) that groups urban, rural, and periphery media. Founded in 2021 by 13 members, its ranks doubled to 26 by the end of 2022. This hyperlocal Pakistani media is being recognised for its focus on social groups marginalised by mainstream media, including women and religious minorities.

A report by DigiMAP said its platforms in 2022 published 100 pieces on the rights of religious minorities, a 92 per cent increase from the previous year. This increased the visibility of unique minority groups by 80 per cent. The content was generated by 140 per cent more sources from local communities (204 in 2022 compared to 85 in 2021). Women’s representation in the content also increased: 84 per cent more women sources were recorded in 2022 compared to 2021.

In terms of impact, in August 2022, an administrator in Chakesar area of district Shangla in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, used local government funds for the renovation and maintenance of a crematorium used by the small Sikh community residing in the area. Crematoriums are rare in Pakistan because Muslims bury their dead, and the few crematoriums are only used by religious minorities such as Hindus and Sikhs. The administrator was motivated to spend the funds after The Pen PK, a member of DigiMAP, published a report on the unprecedent social relations between different faith communities in Shangla.

The biggest challenge for this media community is business viability, as it is increasingly becoming a home for content produced by freelancers sacked from their jobs, and comprising platforms often run by a few journalists driven by passion rather than adequate financial resources.

In 2023, DigiMAP plans to conduct surveys and undertake collaborative business sustainability initiatives to help test various viability models.

Strengthening media institutions was also recognised as a much-needed intervention by IFJ’s national affiliate, Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ). Two financial strengthening projects were undertaken with the Khyber Union of Journalists (KHUJ) and the digital journalist media alliance DigiMAP and completed in the period under review. Digital organising initiatives with the Rawalpindi Islamabad Union of Journalists (RIUJ), the Young Journalist Forum Lahore (YJFL) and the Digital Media Alliance of Pakistan (DigiMAP) supported by the IFJ, highlighted the need for organising female and young digital journalists who are currently outside the union fold.

There is a growing realisation about how disinformation is adversely impacting the country’s socio-political milieu and contributing to political conflicts and media crises.

Journalists and employees from ARY News protest in Karachi on August 16, 2022, after the outlet was forced off air by the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulations Authority. ARY and Bol News were both subject to closures and censorship, with staff arrested or served legal notices on several occasions. Credit: Asif Hassan / AFP

International lens

In terms of meeting its international obligations specifically dealing with the safety of journalists, a report measuring Pakistan’s progress in implementing the UN Plan of Action on Safety of Journalists and Issues of Impunity, was launched by IRADA at an international conference in Islamabad in December 2022 attended by Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif. The report showed that Pakistan had partly delivered on promises to protect its journalist community, mostly through efforts by civil society, media and the UN since 2012, but emphasised the need to effectively implement new laws to ensure perpetrators of attacks on journalists were held to account.

The report’s findings show that various stakeholders of journalists’ safety in Pakistan have together produced significant actions with short to medium-term implications, giving the country an overall score of 1.64 on a scale of 0 to 3. However, the report notes that this performance has not been able to reduce or end the impunity for attacks on journalists, meaning the attackers and killers of journalists still go unpunished.

In January and February 2023, Pakistan was up for its UN Universal Periodic Review at its 42nd session. Key sections of the state of human rights that Pakistan had to answer for related to media freedoms and safety of journalists. In its National Report, Pakistan touted the promulgation of the landmark Protection of Journalists and Media Professionals Act, 2021. It claimed that provincial governments had taken a proactive approach to safeguard journalists and investigate cases pertaining to human rights defenders and journalists. It said the Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa adopted the Journalists Welfare Endowment Fund (Amendment) Act 2019 to provide for the welfare of veteran journalists aged 60 and above in case of, inter alia, death or injury. The Government of Punjab established a PKR 50 million (USD 180,000) fund to support affected journalists or their families with grants up to PKR 100,000 (USD 350). The Government of Balochistan established the Journalist Welfare Fund to compensate journalists for any serious injuries, and, in case of their death, to their family members.

Summarising the concerns of various stakeholders, including Pakistani civil society, the UN Office of the UNHCR indicated that the emphasis should be on media freedoms. Some of the demands from Pakistan included that the Protection of Journalists and Media Professionals Act be amended, in particular Section 6, to avoid broad and vague formulations that lack legal clarity and may be used to unlawfully restriction the right to freedom of expression.

The Digital Rights Foundation stressed that safeguards should be implemented for protected speech by journalists and human rights defenders in online and offline spaces, particularly their right to speak critically of public figures and institutions. Group Joint Submission urged Pakistan to establish without independent commissions for the protection of journalists and media professionals to tackle impunity in crimes against journalists as required under the Protection of Journalists and Media Professionals Bill, 2021, and the Sindh Protection of Journalists and Other Media Practitioners Bill, 2021, and to establish and strengthen mechanisms for ensuring the safety of journalists, particularly women journalists and those from minority communities.

Countering disinformation

In the period under review, Pakistan continued to grapple with the disinformation problem afflicting the media landscape. Media and civil society responses to counter disinformation have seen limited success in the face of conceptual, technical, and financial challenges. A Freedom Network study released in early 2023 examined how Pakistani journalists are negatively affected by online disinformation, which includes potential physical harm as well as psychological and reputational harm, especially to women journalists who are disproportionately targeted.

On the plus side there is a growing realisation about how disinformation is adversely impacting the country’s socio-political milieu and contributing to political conflicts and media crises. Journalistic and fact-checking responses to counter disinformation in Pakistan have struggled due to the lack of conceptual understanding of disinformation among journalists, monetisation trends that incentivise sensationalist news over accuracy, structural issues in the news industry that reduce impact of capacity building initiatives, the lack of financial sustainability of responses, and language barriers.

The study also confirmed previous research findings that disinformation is threatening the work and safety environment of Pakistani digital journalists. Around 60 per cent of the journalists surveyed said disinformation had increased their risk of getting deceived by fake social media posts during online newsgathering. In addition, most women journalists (56 per cent) surveyed said they were targeted with gendered disinformation campaigns, which caused them physical, psychological or reputational harm. A majority of the women (89 per cent) said that they face additional challenges to counter disinformation due to their gender identity. Over two-thirds of the digital journalists identified fact-checking training as their most urgent need to counter disinformation. The study also recommended the establishment of a ‘coalition against disinformation’ comprising journalist unions, academia, media houses and civil society to improve literacy on the subject.

In terms of regulation and action against disinformation, there were instances that demonstrated both a desire to counter the more adverse impact of disinformation as well as a proclivity to hound journalists in the name of countering defamation. For instance, amid a political conflict between Pakistan’s political parties and military establishment, a UK-based Pakistani YouTuber with a military background made startling claims regarding illicit relations between film actresses and military officials. This drew protests and an intervention from the courts. In January 2023, the Sindh High Court accepted the plea of some of the actresses and ordered telecom and internet regulator PTA to block any defamatory and scandalous content against the women on social media sites. In May 2022, the PTA blocked two fake Twitter handles associated with retired army officers promoting the narrative of a political party.

The nature of the challenge of countering disinformation for Pakistani journalists and newsrooms was highlighted in a late 2022 study in which 20 per cent of the journalists surveyed reported they had self-learnt fact-checking tools and skills, while 30 per cent indicated that they had self-learnt how to gather news through social media. Only 10 per cent reported they had been provided with digital tools by their newsrooms. At least 70 per cent journalists indicated that they fact-checked their stories independently. A majority indicated they have not had any formal training on using digital fact-checking tools or newsgathering on social media. Most newsrooms surveyed were found understaffed and lacking in financial resources, making it challenging to establish a dedicated fact-checking desk or team.

There is a growing realisation about how disinformation is adversely impacting the country’s socio-political milieu and contributing to political conflicts and media crises.

Members of the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists, meet during a focus group discussion with freelance journalists on October 18, 2022, in Thatta. Credit: PFUJ

Coalitions for change

In November 2022, the PFUJ launched a campaign demanding justice for senior journalist Arshad Sharif who was murdered in Kenya under mysterious circumstances.

In January 2023, PFUJ staged nationwide protests to demand several concessions, including the release of several detained journalists. Also in January 2023, PFUJ affiliates staged countrywide protests against the harassment of Rana Azeem, its secretary general, as well as against the registration of cases against several other journalists on different charges including defamation and sedition.

Walking the talk on inclusion, the FEC (Federal Executive Council) of the PFUJ accepted the membership of digital journalists and amended its constitution to allow working journalists who had lost their jobs to retain membership of the union or press club. Granting membership to young journalists and freelance journalists began, following a baseline survey of freelance journalists in Sindh province. A quarterly labour rights bulletin published by the IFJ was launched in 2022 to highlight success stories, communicate key developments in the media and review progress on labour rights reform action.

In February 2023, the Commission for the Protection of Journalists and Other Media Practitioners (CPJMP), established by the government of Sindh province, agreed to collaborate with the Pakistan Journalist Safety Coalition to build capacity and start taking up cases of attacks against journalists. The meeting agreed to adopt the UNESCO recommended “3P” approach of prevention, protection and prosecution to combat impunity.

Several advocacy efforts and campaigns for justice for journalists killed and for safety of media practitioners were undertaken in Pakistan in the period under review. Each small step towards enhancing safety for journalists sends across a loud message: media workers matter.