AFGHANISTAN

Standing Strong

Lima Spesaly, a 1TV presenter wears a veil during a live broadcast on May 28, 2022. Women in Afghanistan’s media face ongoing restrictions, with Taliban spokesperson Mohammad Akif Sadeq Mohajir threatening on May 29, 2022, that any female journalists appearing on television without a face-covering would be removed from work. Credit: Wakil Kohsar / AFP

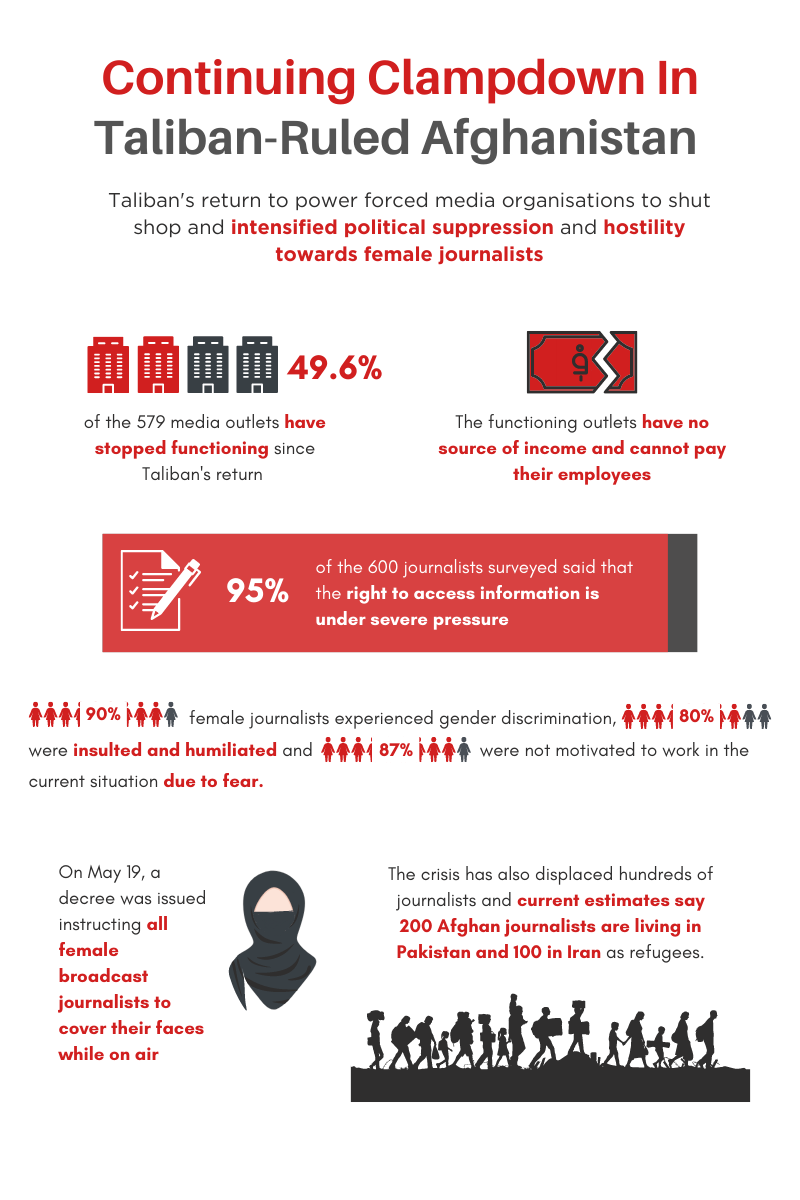

Freedom of the press and the right to access information in Afghanistan saw its darkest days in 2022. With the violent return of the Taliban to power in Afghanistan in August 2021 and the imposition of unprecedented restrictions on journalists and media, the quality and quantity of media reports and access to information fell significantly. Across the country, many media outlets became dysfunctional as they failed to attract advertisements from local businesses which remained the only potential source of revenue after the collapse of international financial support.

According to a survey by the Afghan National Journalists Union (ANJU) published in January 2023, of 579 media outlets previously operating in the country, only 292 remained functional by the end of 2022. In the period after August 2021, as many as 99 radio stations stopped operating. Another study by Pajhwok Afghan News (Afghanistan’s largest independent news agency) revealed that less than half, or 203 of 476 radio networks (43 per cent) were still functioning. Alongside this countless journalists, who were the main bread winners for their families, lost their jobs. Media offices currently still operating in the country are struggling, but don’t pay employees regularly; and most journalists work without a salary.

Women journalists have been especially hard hit in the period in review. The ANJU survey, supported by UNESCO, revealed that 80 per cent of women journalists lost their jobs in Afghanistan’s radio sector alone and 91 per cent of those surveyed were in need of financial support.

Media companies and journalists alike in Afghanistan today face the double challenge of political repression and economic hardship in the current climate. Though no strangers to hostile political leaders or shoestring budgets, Afghanistan’s media and its workers are now in desperate straits and need help to survive.

Two steps back

The right to freedom of expression, approved in Article 34 of the Constitution of Afghanistan in 2003, was once regarded as one of the greatest achievements of the former government. Despite ups and downs, it meant that citizens, journalists and the media could express opinions without fear of harassment or interference from government agencies. However, when the Taliban took over, the constitutional values of freedom of expression, the right to access information, and the right to pursue journalistic work also lost all meaning.

In today’s Afghanistan, journalists say they cannot freely follow news subjects or write critical reports against the Taliban. In one case, a journalist in Kabul was arrested merely for using the words “Taliban” and “supervisory government” in a story. French-Afghan journalist Mortaza Behboudi was arrested in January soon after he landed in Kabul, and remaining in jail despite mounting international pressure demanding his release.

The Taliban’s attitude toward the press is both ideological and pragmatic. From 1996 to 2001, the group outlawed all media platforms except its own Voice of Sharia Radio. During this period, targeted bombings and assassinations saw many journalists killed. However, some Taliban representatives in recent years have seemed more conciliatory to the new independent media, recognising that they do inform public opinion.

Yet, despite distinctions between “Taliban 1.0” and “Taliban 2.0,” the movement’s fundamental stance towards independent media has been consistent. The Taliban expect media to support their mission of creating a society in accordance with their interpretation of Islam. Independent media are inherently suspected of sedition against state and religion. Entertainment, including music and TV serials, according to them, promote immorality and threaten their vision of society. Family honour and religious virtue are closely connected to female seclusion, and women are not encouraged to be visible in public life. The Taliban have been more liberal in Kabul and northern cities but more aggressive in Kandahar and the south. As a result, half the country’s provinces no longer have any women working in the media.

Media Rights Violations

Killings

Arrests

The Taliban expect media to support their mission of creating a society in accordance with their interpretation of Islam. Independent media are inherently suspected of sedition against state and religion.

Afghan journalists attend a press conference on May 24, 2022, in Kabul. The Taliban’s restrictions on access to information have reduced the capacity for journalists to produce stories outside of official narratives. Credit: Wakil Kohsar / AFP

Cracking the whip

Numerous players within the Taliban regularly intervene in media affairs. The Ministry of Information and Culture (MoIC), the Government Media Information Center (GMIC), and the Ministry for the Prevention of Vice and Promotion of Virtue (MPVV) have all issued vague rules with unclear legal bases or consequences for the media.

The MPVV has banned programs with women actors and requires women news presenters to cover their faces. Other rules call on media to refer to the “Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,” respect Islamic values, and coordinate reporting with state overseers. Meanwhile, the General Directorate of Intelligence (GDI) operatives have cracked down on the press, by watching, detaining, and beating journalists and visiting newsrooms to threaten workers and complain about coverage.

The various restrictions have evolved over time and vary by region. At the provincial level, intelligence departments, GMIC directorates, individual commanders and governors all enforce their own redlines, demands and bans. The “no-go” topics include anything perceived to be against Islam, against “national interest and unity”, any focus on attacks by the ISIS (Daesh) and reporting on casualties of these attacks.

Notwithstanding regional variations and differences in tone between the media savvy MoIC and the hard-line MPVV, there is a unity of direction among the Taliban. They constrain independent journalism, cultural programs that do not serve their agenda, and in general restrict women.

Cash-strapped

Compounding problems, the pillars of financial support for journalism have collapsed. From 2001 to 2021, Afghanistan’s economy was largely dependent on foreign aid, all of which was suspended following the Taliban takeover. Sanctions were imposed, Afghan foreign exchange reserves were frozen, and the banking system continues to be largely paralysed. The country is now also witnessing a severe humanitarian crisis.

Unsurprisingly, the international withdrawal has severely affected the media. Though some media aid implementers are finding ways to continue working in Afghanistan, the overall system for news organisations to solicit support from donors and implementers has broken down. Donor governments are focused on diplomacy and humanitarian relief rather than media development.

Governments and development agencies exit from the advertisement market, combined with Afghan businesses’ tightening budgets, has caused the loss of most advertisement revenue for media operations. The situation is even more bleak for newspapers; which have shifted to web-only publishing and are struggling to monetise online content.

Provincial media have experienced extreme revenue erosion; dozens of outlets have closed. Some larger media outlets that do remain operational inside Afghanistan rely heavily on affiliated businesses such as logistics and telecoms, but which ultimately could damage their journalistic independence credentials.

According to a media owner who preferred to remain anonymous, “A major part of our income was commercials, and by imposing restrictions and banning the broadcast of various films, music and entertainment programs, we have lost most of our viewers. Our broadcasts are limited to Islamic programs and documentaries, so businesses no longer trust us to advertise their products because it is clear that such programs do not have viewers to attract the advertised product.”

The weak economy has caused a significant decrease in advertisements on television. For example, during the republic years, various foreign institutions supported the income of this sector by launching programs for women, youth and children through the media. But all this has dried up under the Taliban.

Freelance journalist Somaiya Nosrati says that the economic situation of journalists was so dire that they had to sell home appliances to buy food. As per data from Nai-Supporting Open Media in Afghanistan, many journalists currently receive only about 30-40 per cent of their salaries.

According to the Union of Independent Journalists of Afghanistan (AIJU), when the Taliban arrived, there were 601 media outlets including radio, television, news sites, newspapers and magazines with about 12,000 media employees, 2,800 of whom were women. After the Taliban takeover, about 224 media outlets stopped operating due to economic problems and a few due to the imposition of restrictions, and 8,000 media workers, 230 of whom were women, also lost their jobs.

Though some media aid implementers are finding ways to continue working in Afghanistan, the overall system for news organisations to solicit support from donors and implementers has broken down.

A member of the Taliban stands guard along a road as Taliban fighters arrive at a military street parade in Herat on April 19, 2022. Since taking over Afghanistan in August, 2021, The Taliban has restricted independent journalism and content that does not serve its agenda. Credit: Mohsen Karimi / AFP

Right to access information

Before the Taliban’s return to power, the right to access information was codified by a law enacted in 2014 and amended in 2018. Currently, access to government information is one of the biggest problems for the media in Afghanistan.

The Taliban has since blocked access to information and invalidated the law allowing the right to access information and the only information available to journalists is that which shows the Taliban government in good light. The problem is magnified for female journalists because women’s requests for interviews and obtaining information are directly rejected by the authorities, and women find it very difficult to participate in news conferences.

In the past, all government offices had a department of public relations, but the Taliban government does not follow that practice, and none of their officials responds to reporters. According to a survey of 600 Afghan journalists conducted on December 20, 2022, by NAI-Supporting Open Media in Afghanistan, more than 95 per cent of journalists believe the right to access information has been severely restricted or censored, and is under severe pressure.

New media era

The local, hybrid, and international media experience different levels of Taliban oversight. That impacts their capacity to operate effectively within the country and obtain access to financial support. It is no surprise that there has been a great amount of adaptation to face these new challenges.

A SWOT analysis of Afghan media conducted by IPS Academy in February 2023 showed that its weaknesses were: lack of revenue generation; decreasing quality of human resources; disengagement of females – as both audience and workforce; withdrawal of agency funding; and a lack of media literacy within the administration and among the public. The role of the media was unclear, as there was a lack of awareness about which media houses were now actually independent and which ones were carrying out the propaganda remit.

Threats identified were the lack of a working legal framework (or constitutional vacuum); lack of an independent commission for media issues; lack of a single point of contact for official guidance; decreased revenue due to shrinking market size; and an administration suspicious of the media’s past Western connections, agenda and values.

Strengths identified were public support based on past stories which reflected their issues (legacy reporting) and the sacrifices that continue to be made; the ground presence despite significant risks; geographical (34 provinces were covered in the study) and social reach of media; and media resilience reflected in their willingness to survive and continue.

The opportunities for independent media were identified as: making media presence a necessity for the new administration; packaging the message in ‘Islamic’ terms, if possible, in some cases; strengthening public support by continuing to reflect on genuine issues (sanitation, water, etc.); and media organisations/personnel being allowed to continue engaging with the public and the administration.

The problem is magnified for female journalists because women’s requests for interviews and obtaining information are directly rejected by the authorities, and women find it very difficult to participate in news conferences.

Television journalist and university student Farkhunda Muhibi is one of a few women journalists who have been able to continue work in the media sector. A decree enacted in May 2022, forced all women to cover their faces while on air, among other a number of suffocating restrictions on women’s work, travel and appearance. Credit: Lillian Suwanrumpha / AFP

Crackdown on women journalists

The destruction of the republican system by the Taliban has had devastating effects, especially on female journalists.

The Taliban has put increasing restrictions on women journalists. Following the issuance of “religious guidelines” regarding the role of women on television in November 2021, the first law restricting women journalists was enacted on May 7, 2022, which prohibited women journalists from appearing in front of the camera without long garments, hijabs, and face coverings.

Then, on May 19, 2022, Taliban’s Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice (MPVV), the new avatar of the previous Ministry of Women’s Affairs, issued a ‘final and non-negotiable’ decree instructing all women television anchors and broadcast journalists to cover their faces while on air. The International Federation of Journalists condemned the decree and went on to urge the Taliban to allow all women journalists to work independently and without interference.

Ministry spokesperson, Mohammad Akif Sadeq Mohajir, said that any female journalists appearing on screen without a face-covering would be forcibly removed from work, while Taliban spokesperson, Zabihullah Mujahid, argued that the new rules would help women journalists maintain their family’s modesty and honour.

Journalist Marwa Kohestani, who continues to work in Afghanistan, says that women rarely get permission to enter news conferences and government officials often refuse to be interviewed by women. Another active journalist Fatemeh Lashkari says that she was banned from participating in an exhibition in Herat because she was a woman. Women’s coverage of field reports is weak due to the imposition of restrictions, and critical perspectives are missing from field reportage.

Freelance journalist Rasool Shahzad says that women who continue their media work in the current situation are real heroes, particularly given their economic situation. According to a report published by Zan Times (Women’s Times), the small number of women journalists left are working without salaries. Marwa Jalil, a female journalist in Badakhshan province in northern Afghanistan, earned 17,000 Afghanis (USD 195) before the fall of the republican government, but she has now been working for more than a year without salary. Narges Ansari, another journalist, says that sometimes she doesn’t even have a taxi fare to get to work.

According to a survey conducted by the Afghan National Journalists Union (ANJU) in 2022, gender equity has taken a severe blow under the Taliban regime. It found that 87 per cent of women journalists reported gender discrimination; 79 per cent said they had been insulted and threatened, including with physical, written and verbal threats, by Taliban officials; while 87 per cent of women journalists said they were not motivated to work in the current situation due to fear and panic. Significantly, 91 per cent of working women journalists reported being the sole economic support of their families.

Attacking the messenger

A report by the Afghan Journalists Center recorded 260 cases of media freedom violations and threats, arrests and violent treatment of journalists in 2022. Except for a few cases, most of the arrests, threats and torture were carried out by the Taliban, especially the security forces and employees of the Intelligence Department.

In 2021, during the fall of the republican government and the return of the Taliban, 109 cases of violence against journalists, including the murder of eight journalists, were recorded. But 2022 statistics show that the level of violence against the media and journalists increased by 138 per cent.

AIJU confirms 85 cases of violence and detention of journalists during 2022 and says that the two sides have different interpretations. The journalists call it temporary detention, but the Taliban intelligence group calls it a “discussion” on violations by the journalist and their unprofessional and unbalanced reports.

The attack on March 11, 2023, in Balkh in the north of Afghanistan, showed the insecurity with which journalists in Afghanistan operate. The explosion in Tabian Cultural Center, in a gathering of journalists where many were supposed to be honoured for their work, killed two journalists and injured 14 others. Hossein Naderi, a reporter, and Akmal, a journalist student, lost their lives in the attack later claimed by ISIS.

Two Afghan journalists, Ali Akbar Khairkhwa, a reporter for local newspaper Subh-e-Kabul, and Jamaluddin Deldar, head of Gardiz Voice Radio in Afghanistan’s Paktia province, both reportedly disappeared from Kabul and their whereabouts remain unknown since May 24, 2022. In separate incidents in late May 2022, Taliban intelligence agencies detained three media workers in Kabul and Herat for their reporting.

On May 29, 2022, journalist Roman Karimi and his driver, Samiullah, were detained and beaten by a Taliban intelligence agent while covering a women’s protest at the Haji Yaqub roundabout in Kabul District 10 for Salam Watandar radio station.

Ministry spokesperson, Mohammad Akif Sadeq Mohajir, said that any female journalists appearing on screen without a face-covering would be forcibly removed from work.

A wounded journalist covered in debris holds a tripod near the site of an explosion in the northern Afghan city of Mazar-i-Sharif on March 11, 2023. According to the AIJU, Media rights violations in Afghanistan, including assault, detention, and harassment, have significantly increased since 2021. Credit: Atif Aryan / AFP

Adapt or die

Media with accreditation and offices in Afghanistan must now follow the new rules. Talk shows now feature Taliban spokesmen; reports are increasingly sourced from Taliban channels and the owners of some major media outlets are getting closer to the Taliban to advance their business interests, for example, ownership of mobile networks.

Local media have learned to avoid reporting directly on sensitive issues, whether women’s rights or the anti-Taliban insurgency in Panjshir in north-eastern Afghanistan. There is space for public service reporting; content about health, agriculture, and the economy; educational programs; and stenography of press conferences. Within these constraints, journalists are finding space for free expression. While reporting acceptable topics, framing arguments in Islamic terms, or citing UN reports, local media offer subtle criticism and information undermining Taliban narratives.

Local journalists are now using the gaps in Taliban surveillance to continue reporting. While the Taliban have stepped up policing of social media, they do not comprehensively monitor broadcasts. Radio and television programs sometimes feature content that crosses Taliban redlines and goes under the radar of the censors. It is terrestrial broadcasts that reach most Afghan citizens, given the low literacy levels and internet penetration in the country.

The few women journalists who remain must contend with restrictions on how their faces and voices will go on air, not to mention the extra challenges of reporting in the field or even reaching workplaces. The Taliban also require that male relatives escort women when travelling, and women journalists say that their families are reluctant to let them leave the house for fear of violence.

Many prominent national media outlets have adopted hybrid local-international models of reporting and some have restructured the process so that anonymous in-country contributors feed information to journalists abroad who author the stories. Pajhwok Afghan News has adopted a learning model in which senior journalists abroad mentor less-experienced in-country colleagues.

Survival tactics

Given the current situation, some media are revisiting their business model and gradually moving towards hybrid models where their domestic presence and work is supplemented with overseas media supporting activities.

Hybrid media outlets that have closed their offices in Afghanistan, but still rely on contributors within the country, also face trade-offs in editorial control and safety. On the one hand, the Taliban have less power to direct the content and style of their reporting and reporters contributing to their coverage manage to work without Taliban permission. But on the other hand, these reporters can’t attend public events, interview Taliban face-to-face, or report in rural areas or crime scenes where they face suspicion and they risk being reported to authorities.

Data safety and internet access are major concerns for these emerging hybrid outlets. As a result, they are adopting secure communication practices between contributors inside and outside the country.

The Taliban have a history of targeting telecommunications infrastructure and have repeatedly shut down the internet, during the 2021 protests and in Panjshir during the fighting there. Internet is slow and inaccessible outside major cities, restricting the newsgathering capacity of reporters as well as the reach of news published online. But the Taliban are not systematically filtering the internet or surveilling private communications.

Hybrid media with foreign bank accounts are better positioned than purely local media to receive international support. This means they can transfer funds to in-country contributors using a combination of the informal hawala system of money transfers through agents, which circumvents problems of sanctions and Taliban tracking of formal banking transactions. But Hawala dealers charge steep transaction fees and do not provide records that satisfy donors’ reporting requirements.

These hybrid media outlets must also contend with higher costs of living for their contributors outside of Afghanistan and higher operating costs abroad. In some cases, they need legal assistance to register as businesses and set up accounts in those countries.

So too, journalists seeking to independently cover Afghanistan have become more reliant on social media and information from activists and citizen journalists in the country. Traditional investigative journalism within Afghanistan has all but disappeared. These limitations are especially acute for media-in-exile like Afghanistan International TV which does not have on- ground operations.

Paradoxically, foreign media such as the BBC, VOA and Al Jazeera have more freedom to report within Afghanistan than their local counterparts. Their visiting journalists enjoy relative immunity as the Taliban attempt a charm offensive with the international community. Foreign outlets have been able to negotiate permission to report on sensitive topics like drug addiction and trafficking.

Even as foreign outlets have been allowed to carry news from Afghanistan to the outside world, the Taliban have blocked Persian and Pashto language services from the same outlets from reaching Afghans. The Taliban banned terrestrial television and radio stations from rebroadcasting foreign-produced programs in March 2022. This measure not only struck a blow to foreign channels, but also cut off a revenue stream for local media which is paid to rebroadcast that content.

Media support institutions

From 2001 to 2021, several civil society organisations (CSOs) emerged to support media: The Afghanistan Journalists Federation (AJF) as an umbrella professional association; the Afghan Journalists Safety Committee (AJSC) to monitor press freedom violations and aid journalists under threat; Nai-Supporting Open Media in Afghanistan (Nai-SOMA) to train journalists and coordinate investigations; the Free Speech Hub (FSH), a member-based network of journalists that also served as a coordinating body for leading journalists and media leaders.

These bodies worked with existing unions such as AIJU and ANJU to further freedom of expression. CSOs monitored and protested rights violations and advocated for legal reform. Even under the new regime, CSOs have had success in negotiating the release of arrested journalists and appealing local policies to the Taliban central leadership.

However, the Taliban have taken steps to censor and co-opt CSOs. The Taliban stopped AJSC from publishing reports about attacks on the press; the committee continues to compile data privately. The General Directorate of Intelligence (GDI) cancelled a January 2022 press conference of the AJF, Nai-SOMA, and FSH, detaining speakers and organisers. The Taliban supports the newly launched Afghanistan’s Journalists and Media Organizations Federation, which promotes the Taliban regime’s agenda while creating the appearance of civil society engagement.

Afghan media professionals and observers anticipate that the Taliban will further clamp down on media if they remain in power. Journalists and their supporters must therefore prepare for the worst even as they make the most of what space remains.

The Taliban have long spread their message through magazines, open letters, radio transmissions, and more recently websites and social media. The Taliban might create more state-run media outlets and support nominally private media companies to create the outward appearance of media pluralism. Individual Taliban leaders might sponsor their own outlets, following the 2001-2021 pattern of political leaders and parties launching and controlling their own media outlets.

The Taliban is also taking to social media to spread their message. In January 2023, using the new Twitter Blue Service, the Taliban purchased verified accounts whereas earlier the blue tick used to indicate “active, notable, and authentic accounts of public interest” verified by Twitter, and could not be purchased. After outrage from several quarters, the blue ticks were removed, but quietly reinstated later.

The government might also use registration, accreditation, and taxation processes to systematically marginalise and pressurise the rivals of their favoured media outlets. The Taliban might also expand and tighten rules on the terminology and Islamic orientation of media content, as well as further restrict the role of women, for example by segregating newsrooms by gender.

Taliban fighters have publicly shared footage of their actions, providing a record of their atrocities, but the collective has learned to restrict its fighters’ use of social media. Greater discipline among the Taliban and more policing of phone filming and social media sharing may dry up the supply of eyewitness footage on which independent journalists increasingly rely.

Local journalists are now using the gaps in Taliban surveillance to continue reporting. While the Taliban have stepped up policing of social media, they do not comprehensively monitor broadcasts.

Afghan media professionals and observers anticipate that the Taliban will further clamp down on media if they remain in power. Journalists and their supporters must therefore prepare for the worst even as they make the most of what space remains for them.

The Head of the Taliban’s Ministry of Information and Culture, Khairullah Khairkhwa, attends the opening ceremony of a museum in Kabul. The Taliban have long spread their agenda through press conferences, magazines, open letters, radio transmissions and, more recently, social media. Credit: Benjamin Guillot-Moueix / Hans Lucas

Furthering the surveillance agenda

The Taliban have resorted to shutting down internet access temporarily at times of unrest. New economic and security ties with illiberal states may increase access to expertise, technology, and investments to enhance internet censorship and surveillance capacities.

The Taliban hope for international recognition, release of foreign exchange reserves, and sanctions relief. Liberal democratic states can currently pressure the Taliban on rights issues. But this détente may not last. The Taliban may abandon diplomatic outreach to the democratic world and adopt a survival strategy based on ties with illiberal states. Such a geopolitical turn would accompany a hardening of media policy and loss of leverage for the international community.

Taliban foreign relations might also influence hybrid and international media’s ability to operate out of other countries. Afghan satellite television is broadcasting out of the United Arab Emirates and Central Asia; some Afghan media outlets are setting up shop in Turkey. The future of these operations may be contingent upon Taliban making deals with these countries.

A problem for all media in need of international financial support is getting money into Afghanistan. Solutions might include waivers on sanctions to allow media access to the SWIFT payment system, or channelling money to the media through UN agencies with sanctions waivers.

Open internet access and secure communication with colleagues and sources are important to all journalists. Supporters can help Afghan journalists adopt appropriate technology and prepare backup communication systems in case of internet and mobile service blackouts.

What the future holds

International media support should be part of a holistic diplomatic and development strategy toward Afghanistan because of mutual dependence of media with human rights, education, democracy, and humanitarian efforts. Diplomats should raise press freedom issues when negotiating with the Taliban, specifically pressuring them to reduce restrictions on women in the media. Media and other aid should come with conditionalities of rights protections, independence of grantees from Taliban control, ethical standards, and inclusion of women.

The international community should not help the Taliban build a propaganda machine. Efforts to monitor Afghan media have been ad hoc and incomplete. Systematic monitoring is needed to track what media outlets are publishing, as well as the attacks and restrictions on the press. Aid can then more accurately be directed toward independent media.

International supporters can facilitate communication among Afghan media outlets and encourage the strengthening of inter-organisational associations. Though such groups, media and CSOs can form a united front to engage both the Taliban and international donor community.

Local, hybrid, and foreign media can also support each other’s journalism. A journalist accredited with local media might publish uncontroversial reports in their own name and contribute anonymously to hybrid media. A foreign reporter might use their privileged position to coordinate reporting with local partners. A transnational communication network might also include journalists from other countries with lessons from working in repressive environments.

As Afghan media outlets shift to social media as both a newsgathering channel and a channel for reaching audiences, they might learn from organisations experienced in online reporting and monetizing online content. Social media platforms and tech sector experts might also help them develop new revenue streams and ways of connecting with audiences.

Established journalists will benefit from training and technical support on using secure communication technology and safe reporting. Digital journalism training can support the shift to online reporting, open-source investigation, and data journalism. Within Afghanistan, CSOs can restart training programs, albeit under Taliban oversight.

The Taliban have taken over the education system and are revising curricula, including of journalism schools, to conform to their ideology. Programs are needed to train the next generation of Afghan journalists. Mentorship models where journalists abroad collaborate with young colleagues in Afghanistan can be expanded. Girls and women face a ban on education beyond primary school, creating a special need for media training oriented toward women.

Afghan journalism took a heavy blow in August 2021, and since then the Taliban has worked step by step to control the media and its citizens’ access to information. The spotlight of international attention and aid has meanwhile shifted away from Afghanistan, leaving Afghan journalists, especially women journalists, at home and abroad, without the support they need.

But all is not lost for the resilient Afghan media. International supporters can help ensure the survival of independent journalism through financial and diplomatic means and by facilitating communication among media organisations, CSOs, and other stakeholders.