BHUTAN

Information Blockade

Bhutan’s Prime Minister Lotay Tshering and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz hold a press conference in Berlin on March 23, 2023. Despite a lack of transparency from public institutions, Prime Minister Tshering has reiterated his commitment to freedom of information in Bhutan. Credit: John Macdougall / AFP

For journalists in Bhutan, access to information has never been as challenging as over the last few years. The shifting media landscape coupled with the high turnover of journalists is compounded by shrinking access to information, all of which is impacting news coverage and people’s access to information.

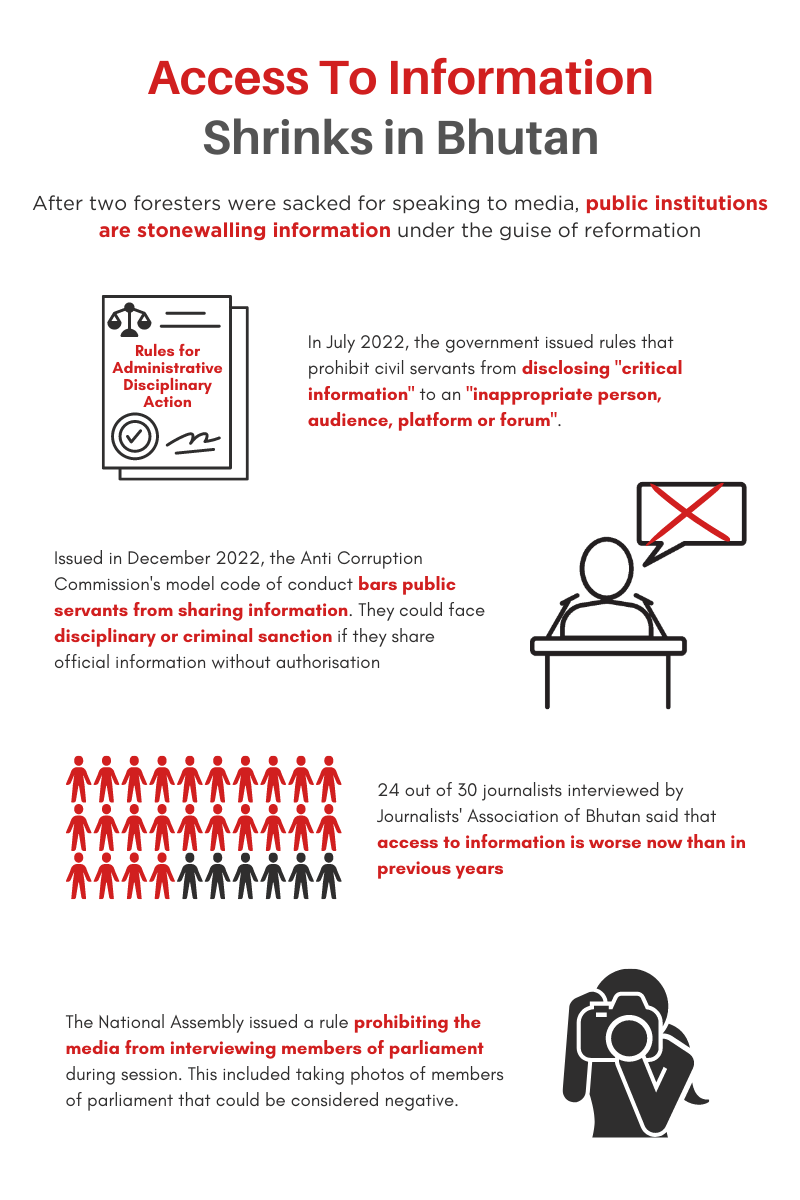

In April 2022, public institutions used the guise of a reformation process to begin stonewalling information, after two female foresters who spoke to the media were forced to retire by their parent agency, the Ministry of Agriculture and Forests. They had alleged that the ministry issued transfer orders based on favouritism and nepotism.

The ministry justified its actions on the grounds that the two foresters had breached Section 3.3.16.2 of the Bhutan Civil Service Rules (BCSR), which restricts civil servants from criticising or undermining government policies, programs and actions in public and/or through the media. The rules restrict civil servants from communicating, transmitting or posting hate messages or any content with the intent to defame a person or government agencies.

In July 2022, the Royal Civil Service Commission (RCSC), which is the central personnel agency of the government, introduced the Administrative Disciplinary Actions (RADA). RADA is now tasked with dealing with civil servants who disclose critical information to an unauthorised person, audience, platform or forum and those who use official information for personal gains. These are classified as major offences.

The price of speech

The strict enforcement of these new rules has further discouraged civil servants and officials from talking to the media even when they are only sharing “necessary information to keep the public informed”. “We don’t want to talk to the media; there will be repercussions,” one senior civil servant said.

Another senior official confirmed that the RCSC had tightened the law. “We can never predict the consequences of talking to the media,” he said.

Lawyer Sonam Tshering, in an opinion piece in Kuensel, stated that the action of compulsorily retiring two foresters for merely speaking to the media and the Ministry issuing a notice barring employees from expressing themselves in the media, showed the extent to which public authorities were using indirect methods to silence or suppress public criticism.

Tshering also said that the curtailment of information from public institutions is on the rise. Following the RADA, the National Assembly came up with a rule prohibiting the media from interviewing members of parliament during session. This included taking photos of members of parliament that could be considered negative. “The institutions failed to realise that such measures are counterproductive and undemocratic and contribute significantly to the loss of confidence in these public institutions,” Tshering wrote.

Article 7 (Section 2 and 3) of the Constitution guarantees the right to freedom of speech, opinion and expression, as well as the right to information. “These rights are guaranteed because the public institutions are accountable to the public,” he stated.

A journalist working for a private newspaper said that his sources among civil servants were not as open as they used to be. “It takes a long time to get information and permissions from the heads of agencies and ministries,” he said.

In 2022, the National Referral Hospital in Thimphu issued a notification cautioning civil servants about sharing information with the media without following due process. Officials from RCSC said that it was common practice for any agency, both public and private, to expect its staff to abide by a code of conduct. “The code of conduct and values reflected in the BCSR 2018 is to ensure integrity, discipline, accountability and effectiveness of the civil servants, which has been diminishing in recent years leading to systemic weakening of the civil service,” they claimed.

A newspaper editor wrote in a column that government officials use or misuse provisions of the civil service rule to hide information and their lapses: “Transparency is one of the pillars of good governance but gagging the media has meant that our officials are unaware of the good governance that they are trying to promote,” he said.

The piece went on to say that the Bhutanese media was not as mature or critical as other media in the region. Only a few journalists ask hard questions. When answers are delayed because of bureaucratic procedures or due to fear of repercussions, it does not help anyone. “Social media is thriving because citizens resort to it when they are restrained through rules,” he wrote.

Today, social media has become an alternative platform for information for many Bhutanese people. Since access to information for mainstream media journalists is being limited, social media gives the possibility of a plurality of voices, which is critical for democracy. People also rely on social media to break news and other developments, although the fact remains that it lacks editorial filters.

Media Rights Violations

Killings

Arrests

The shifting media landscape coupled with the high turnover of journalists is compounded by shrinking access to information, all of which is impacting news coverage and people’s access to information.

Bjabcho Aumtsu Detshen, a parent and member of a community-based organisation empowering single mothers through mushroom farming, is interviewed on July 21, 2022. As more and more journalists, media workers and everyday Bhutanese leave the country, newsrooms are facing a staffing crisis as outlets attempt to fill industry-wide vacancies. Credit: Bhutan Media Foundation

Codes that gag

The Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) has also come up with a model code controlling public servants, which means they could face disciplinary action or criminal sanctions if they share official information, including non-confidential information, without authorisation.

On December 30, 2022, the ACC issued an executive order requiring public agencies to develop and implement an agency-specific code of conduct based on the commission’s model public service code of conduct. The ACC model, which came into force on December 31, 2022, requires a public servant to maintain confidentiality regarding any matter, document, report and other information related to the official function that is in their knowledge. The ACC’s code of conduct will be part of the employment terms and conditions of a public servant and any breach will result in disciplinary or criminal sanction.

ACC officials said that the model code is aimed at ensuring accessibility to official information and responsible public reporting through proper mechanisms. “The requirement of sharing information through authorised persons is to ensure quality reporting with accurate, authentic, and complete information for meaningful civic engagement in the governance system,” ACC Commissioner Jamtsho said. “Any engagement based on inaccurate, false, and incomplete information would only promote mistrust and compromise the rule of law and public order.”

In other countries, he said, access to official information is regulated by law on the citizen’s right to information and secrecy. “There is no such law in Bhutan.”

The commissioner said the model code was not intended to impair the constitutional right to freedom of speech. “It is, rather, intended to complement the duty to exercise freedom of speech responsibly,” he said. “No constitutional rights are absolute. All the fundamental rights are accorded with limitations.”

However, such a code coming from a constitutional office mandated to promote transparency and accountability has caused concern. Media professionals say this worrying trend violates the right to freedom of speech, opinion and expression as well as the right to information enshrined in the Constitution of Bhutan. Such a rule aggravates the already poor access to information, they say.

Tenzing Lamsang, the editor-in-chief of The Bhutanese, said that the model code should not stop public agencies and officials from sharing public information. “Be it any codes, regulations, or acts, if it is not in keeping with the Constitution, it is null and void. All of these should not be ultra vires to the Constitution,” he told Kuensel. “The right to information is not about state secrets, but about public information which is needed for the public,” Lamsang said, adding that the government should share it since the media works to advance the public interest.

This would only impede journalists from covering investigative stories against corruption, he said. “If only authorised civil servants are allowed to talk, how will they expose corruption?”

The editor of Business Bhutan, Kinley Yonten, said such red tape and formalities are unhealthy for democracy and that media has a pivotal role to ensure that a democratic government upholds transparency, sincerity, and accountability. Strengthening free media will ultimately strengthen democracy and promote liberty, he added. “If democracy allows people to determine their own future, that choice or determination must be based on factual and accurate information.”

Another senior journalist said that from now on, the media will struggle to perform its duties. “Such a rule would promote corruption, nepotism, and favouritism in the country with people disallowed to share information,” he said. “This indirectly means that the system does not require media, and it is a really dangerous trend.”

Transparency please

Deeply concerned that the people and agencies holding information or expertise are becoming increasingly cocooned, editors, publishers, the media community and the Journalists’ Association of Bhutan (JAB) appealed to the Media Council of Bhutan to help facilitate better access to information from public institutions.

In their appeal letter, the group stated that access to information had become restricted by “red tapism” and bureaucracy, leading to journalists’ inability to write stories of public interest with adequate clarity and depth. Now even getting basic information meant having to go through several layers of bureaucratic procedures.

The chairperson of the Bhutan Media Council, a statutory body set up by an act of Parliament in 2018, wrote to organisations such as the RCSC, the judiciary, the ACC, and the Office of the Attorney General urging the agencies to respect their mandates and protect freedom and independence of the media. “We would like to request the concerned agencies to kindly facilitate easy access to public information for the media so that they can play their role to inform and educate the people for our shared national goal of an informed citizenry,” the letter stated.

“We share no misconception that any public information made accessible to the media is ultimately not for the media, but for the public,” the Council’s chair stated in the letter. “The media is a critical conduit. For all their limitations, the media share your good intentions for public service in the spirit of transparency and accountability stressed by His Majesty The King.”

“We hope that the concerned agencies will be in a position to support our media by granting freer access to public information…On our part, we will be pleased to facilitate better communication between your institution or organisation and the media.”

With recommendations from editors, JAB conducted a survey in August 2022 on access to information and its findings speak volumes about how difficult it is to get basic information today.

JAB asked journalists to rate various government agencies based on access to information. Of the 30 respondents, 24 said that access to information was worse than in previous years. The survey found that the Prime Minister’s Office received the highest rating, while RCSC and Thimphu Municipal Office shared the worst.

“The right to information is not about state secrets, but about public information which is needed for the public.”

Foreign cadets from Bhutan line up during their graduation ceremony at Chennai’s Officers Training Academy on October 29, 2022 in India. While journalists in Bhutan have managed to largely avoid repression from law enforcement, access to information remains a pressing concerns for journalists and outlets. Credit: Arun Sankar / AFP

Tripping over red tape

The bureaucracy has been the biggest stumbling block for journalists in Bhutan. Interestingly, many media professionals agreed that the elected government is more open than bureaucrats when it comes to sharing information.

Any reporter or editor can call up the prime minister or his cabinet ministers at odd hours for information or clarifications. Such access is impossible in many countries. Prime Minister Dr Lotay Tshering at a “meet-the-press” session in January 2023 reiterated that public servants have a responsibility to share information with the media.

“By sharing the information with the media, they are not doing any favours, they are doing what they are mandated to do and they are doing what they are paid to do.”

“Whatever we do, if it is for public benefit, the public must know. For this important information to go to the public, the media is the only thing that we can ride on,” he said.

In 2022, Bhutan jumped to the 33rd place in the global press freedom rankings from the previous year’s position of 65 out of 180 countries. The outside world is likely to see this ranking as a significant achievement for the tiny Himalayan kingdom with a population of just 700,000. However, despite the improvement in ranking, there continue to be many challenges that journalists in Bhutan face in terms of access to information.

Abandoning ship

There are seven newspapers in the country today: Bhutan Times, Bhutan Today, Business Bhutan, Gyalchi Sarshog, Kuensel, The Bhutanese, and The Journalist. The only television broadcasting station is Bhutan Broadcasting Service (BBS). There are five FM radio stations (BBS Radio, Centennial Radio, Kuzoo FM, Radio Valley, and Yiga Radio).

More than 80 journalists, including 20 from the print media, quit journalism in the past year. In a country the size of Bhutan, with a relatively small industry, the departures represent a significant blow. BBS alone lost 60 employees with news reporters, producers, camerapersons, and editors resigning from their jobs. BBS’ chief executive officer, Kaka Tshering, said that the management is recruiting to endeavour to fill the human resource gap.

A total of 12 newsroom employees, both new recruits and experienced journalists, resigned from Kuensel in the past 12 months also.

Business Bhutan’s editor Ugyen Tenzin said that the number of journalists leaving Bhutan is higher than ever before. Another newspaper editor said that that many are choosing to leave for better opportunities. “Reporters look for better pay and a good working environment,” he said.

Today, newsrooms are stretched to their limits with only a few seniors or experienced journalists, and new recruits frequently leave the profession.

Low salaries, a poor working environment and difficulty in getting information are seen as factors influencing journalists to seek other careers or leave the profession for opportunities overseas.

The way forward

Despite repeated editorials and stories on the lack of access to information published by different newspapers, the situation in Bhutan’s media continues to deteriorate. For years, journalists have been encouraging the public to be active in media and to involve citizens to operationalise democracy, but the media itself is hitting a wall when attempting to access credible information.

Government institutions and ministries have a responsibility to appoint media spokespersons and conduct regular press briefings. They should also relax restrictions on official communications and set a timeline to share public information.

Past attempts to appoint spokespersons in ministries and organisations hasn’t worked because they still had to seek permission to talk to the media. Since time and information is vital, the system of dissemination needs to be made more efficient and transparent.

Public institutions must uphold the supreme law of the country, the Constitution, which explicitly states that power belongs to the people and not to the authorities. The media is merely an information facilitator, and citizens use such verified information to hold the government accountable.