MALDIVES

Riding the Waves

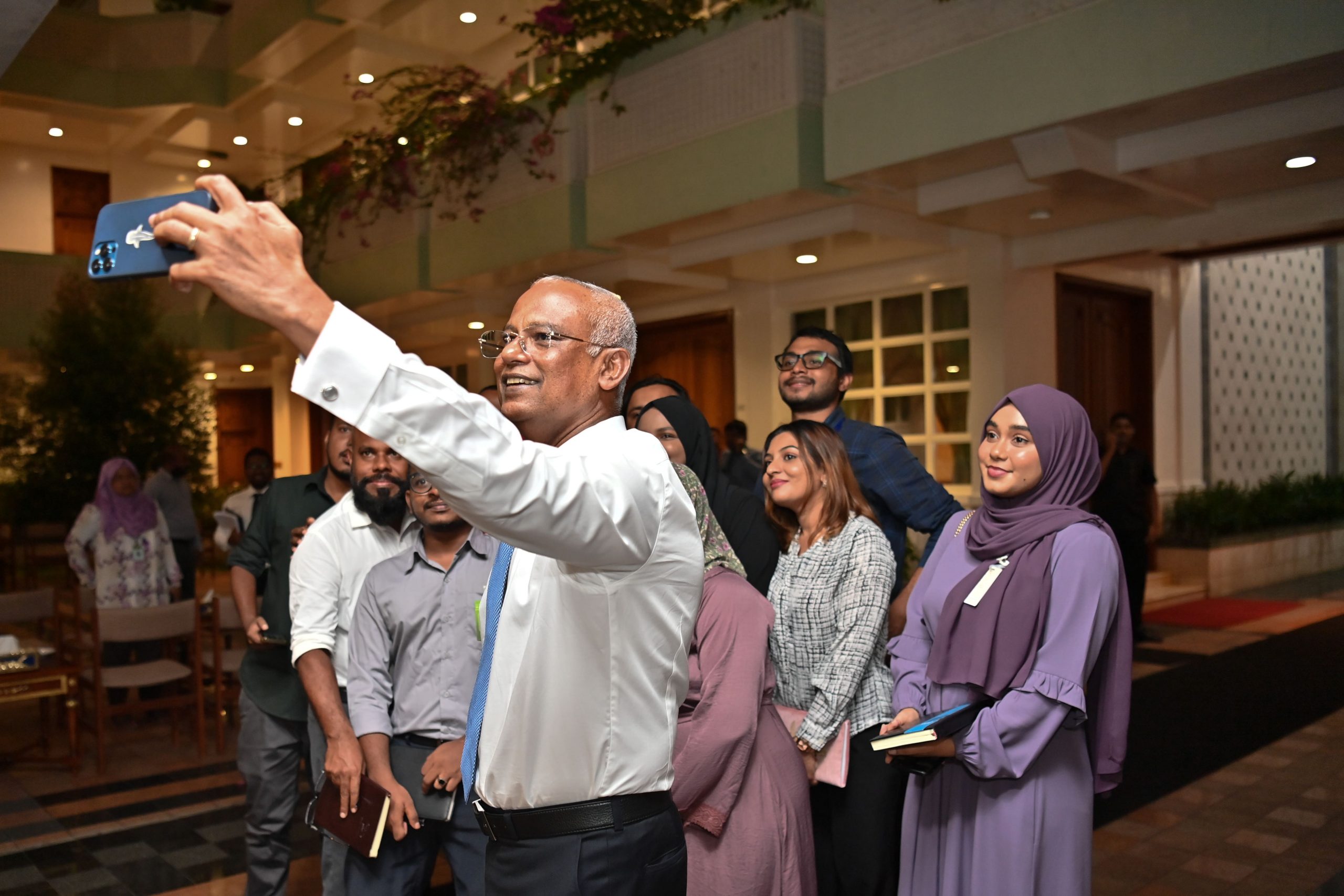

President Solih takes selfie with journalists after press conference on December 28, 2022. The Maldives’ small media sector has allowed government and business interests to flourish. President Solih’s office was revealed to have distributed over USD 64,000 for positive coverage of government projects in early 2022. Credit: MJA

As President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih’s five-year term draws to a close in November 2023, the media landscape in the Maldives remains politicised and encumbered by a lack of independence. Reliant on politicians and business magnates for funding, most news media are openly aligned with pro-government or opposition parties, often promoting their interests without a pretence of impartiality. This leads to biased coverage that changes with the shifting allegiances of benefactors.

After a long history of autocratic rule, a free media emerged in the Maldives as the former strongman relented in the face of an irrepressible pro-democracy movement. The first independent media outlets were registered in 2005, along with the first political parties. The new-found space for free speech expanded after the first democratically elected president assumed office in November 2008. Defamation was soon decriminalised. Critical and hostile coverage of the new administration became normalised.

Press freedom has since been inextricably tied to the country’s democratic fortunes. An authoritarian reversal loomed after former president Abdulla Yameen’s administration came to power in November 2013. Raajje TV’s studio was torched during the presidential election campaign in October 2013. Defamation was re-criminalised in 2016, after which the broadcasting regulator slapped crippling fines on private stations, including USD 230,000 on Raajje TV for allegedly defaming the president. Haveeru, the country’s oldest newspaper, was shut down amid a dubious dispute over ownership. After exposing government corruption, online publication CNM was forced to close when its sponsor withdrew funding. Three Raajje TV journalists were found guilty of obstructing police duty during anti-government demonstrations, becoming the first journalists to be convicted in more than a decade.

Hopes for a democratic revival were rekindled by the election of President Solih in September 2018. As pledged during his campaign, the incumbent repealed the draconian defamation law. A presidential commission was established to independently investigate the unresolved abduction of journalist Ahmed Rilwan in August 2014 and the murder of blogger Yameen Rasheed in April 2017.

The need for vigilance on various fronts continued in the period under review, particularly with regard to financial autonomy of the media.

Follow the money

For the government, advertising by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) – a crucial source of income for the media – has become a useful tool for leverage. The placements of ads by SOEs in new websites without readership begged questions about fairness and the lack of transparency and oversight. Identical advertorials and glowing write-ups were found in multiple outlets. In some cases, editors were allegedly instructed to remove articles or not cover sensitive subjects.

In early 2022, the president’s office was revealed to have distributed more than MVR 1 million (USD 64,000) for positive coverage of government projects.

As more legitimate advertising revenue returned with the recovery of the Maldivian economy from the Covid-19 pandemic, larger mainstream outlets were able to restore deducted salaries. But smaller newsrooms continued to struggle. Despite severe financial losses across the spectrum, there were no forced closures of media houses. The number of registered newspapers and magazines in fact increased from 219 in 2020 to 268 in 2021. The new startups were predominantly news websites in the local Dhivehi language. But not all registered outlets publish regularly, and 47 inactive outlets were dissolved in March 2022. Popular proposals to ensure financial sustainability include government subsidies, low-cost internet packages, and a merit-based process for securing advertising from SOEs.

Nine years after the passage of the Right to Information (RTI) Act, a culture of secrecy persists. Most appeals to the Information Commissioner’s office involved failure of information officers to respond within the mandatory 21-day period. Government ministries and SOEs also mounted legal challenges against the commissioner’s orders for compliance. In February 2023, an RTI activist scored a significant victory when the High Court upheld an order for the Bank of Maldives to disclose staff remuneration. The bank contended that it did not fall within the law’s purview. But the ruling laid out a precedent to bring SOEs in line with the 2014 law, which ranks 16th out of 128 RTI laws in the world. An online portal introduced in May 2022 can now be used to submit requests to 267 state institutions.

Media Rights Violations

Killings

Arrests

For the government, advertising by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) – a crucial source of income for the media – has become a useful tool for leverage.

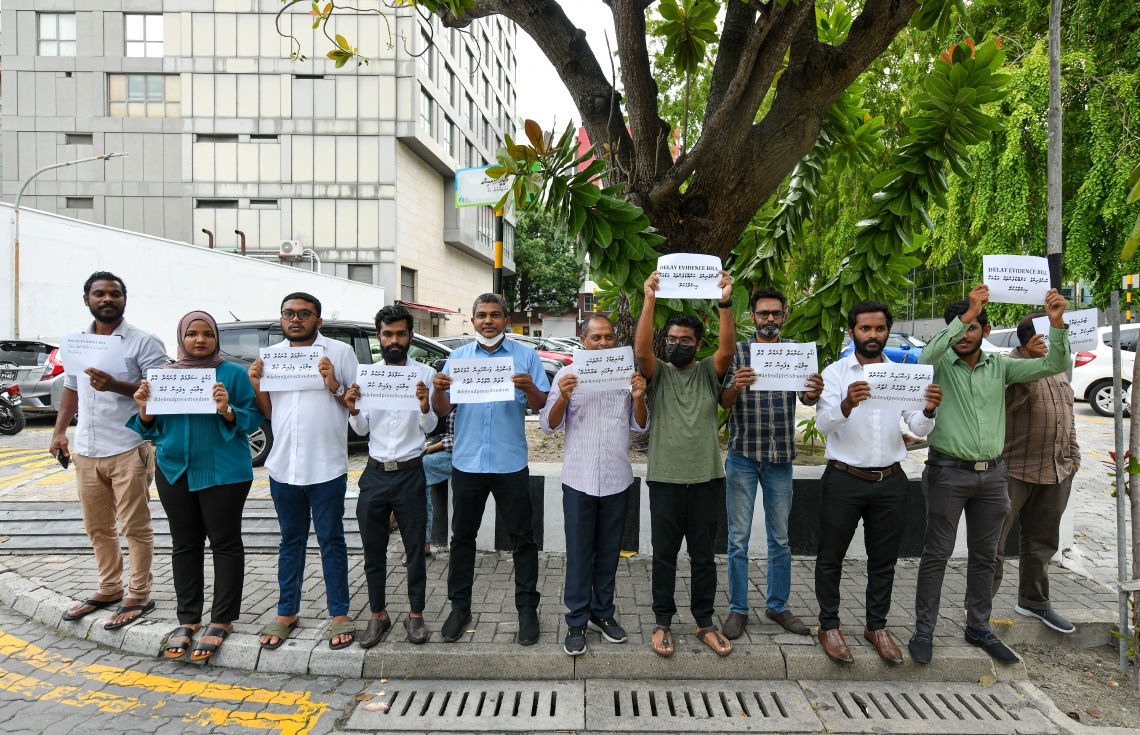

Journalists protest outside Parliament against the passage of the proposed Maldivian evidence bill in June 2022. The ambiguous law allows courts to compel disclosure of anonymous sources for cases involving acts of terrorism or offences related to national security. Credit: Nishan Ali / Mihaaru News

There is a growing realisation about how disinformation is adversely impacting the country’s socio-political milieu and contributing to political conflicts and media crises.

Targeted harassment

Whilst murder, physical assault and abduction of journalists by non-state actors have not occurred in the recent past, media workers continue to face harassment and threats of violence both online and offline. On May 29, 2022, a group of people barged into the Mihaaru newsroom and harassed and threatened staff, alleging misinformation in several articles. A reporter that the group targeted was not in office at the time. Through the year, the newspaper’s journalists faced defamatory personal attacks on social media platforms, which are used by more than 70 per cent of the Maldivian population. In one instance on December 16, 2022, an opposition politician, who previously served as a state minister and customs chief, railed at an award-winning Mihaaru journalist for “prostituting” herself to the government.

In July 2022, a video was circulated on TikTok with the photo and mobile number of Dhiyares journalist Hathima Yoousuf, who faced harassment from numerous phone calls. According to Dhiyares, the harassment came after a defamation lawsuit was filed by a lawmaker against the online portal. All the phone numbers were registered to the MP’s constituents.

On several occasions over the past year, journalists wearing official press passes were subjected to police brutality while reporting on street protests.

A police officer threatened and harassed journalists and camera crew who were covering an opposition protest on May 18, 2022. On June 1, 2022, a police officer pepper-sprayed a Vnews journalist in the face as he tried to film the arrest of a protester. Mohamed Samah, CEO of the opposition-aligned Channel 13, was arrested while covering an opposition protest on January 7, 2023. He was accused of bringing more people to the protest and blocking traffic. But according to Samah, he went to the protest to solve a technical problem with the TV station’s live coverage. The criminal court released Samah but imposed a night-time curfew, prohibiting him from leaving home between 6 pm and 6 am for 30 days.

Channel 13 accused police of singling out its journalists for discriminatory treatment. On February 6, 2023, Channel 13 videographer Hassan Shaheed and cameraman Ahmed Misbah were pepper-sprayed and injured while covering an opposition protest outside parliament. Shaheed suffered a concussion after he was hit by a shield as riot police charged the protesters. Later in the day, Shaheed was flown to Sri Lanka for further treatment.

On March 16, 2023, Avas video journalist Hussain Juman was arrested while covering an opposition protest. A video of the incident showed a policeman pushing him to the ground and throwing his phone away. The police accused Juman of assaulting an officer and sought to keep him in custody, but the criminal court ordered his release.

On March 20, 2023, Adhadhu editor Hussain Fiyaz Moosa received a death threat via text message hours after the publication of an article about gangs and religious extremists.

Managing editor Ahmed Zahir (‘Hiriga’) and a senior reporter and secretary general of the Maldives Journalists’ Association (MJA), Ahmed Naaif from Dhauru were issued serious threats via phone and text on April 7 following the publication of an article about a high-profile arbitration case between a Maldivian tourism group and Hilton Worldwide.

The MJA expressed concern over journalists “constantly being harassed” by the police. Eight violations of media rights have been recorded so far this year, the MJA noted, which was up from six cases each in the past two years.

Whilst murder, physical assault and abduction of journalists by non-state actors have not occurred in the recent past, media workers continue to face harassment and threats of violence both online and offline.

Channel 13 media worker Mohamed Shaheem is tackled to the ground by police while covering an opposition rally in Malé on February 20. That same day, Channel 13 executive Mohamed Samah and the station deputy Hussain Ihsan were obstructed from live-streaming the event. Credit: MJA

Legacy of impunity

In June 2022, three suspects were arrested in connection with the abduction of journalist Ahmed Rilwan. The arrests came after a breakthrough by the presidential commission on deaths and disappearances. After a four-year investigation, the commission presented its final report to President Solih in December 2022. The missing journalist was taken out to sea, beheaded and his body sunk, the investigation concluded. Briefing the press on its findings, the commission accused the previous government of allowing six suspects to flee to Syria.

Four months before the enforced disappearance, the police had obtained a court warrant to intercept Rilwan’s phone conversations, the commission revealed. But despite the surveillance and intelligence information about threats to his life from Maldivian jihadis overseas and a local vigilante group that was targeting suspected atheists in the capital – the police failed to protect Rilwan or alert him to the imminent danger. The extremist group behind the abduction – an al-Qaeda affiliate – also “organised and financed” blogger Yameen Rasheed’s murder in April 2017 and the attempted murder of journalist Ismail Khilath Rasheed in June 2012. The group of radicalised young men believed that the victims deserved to be killed for apostasy or “insulting Islam.”

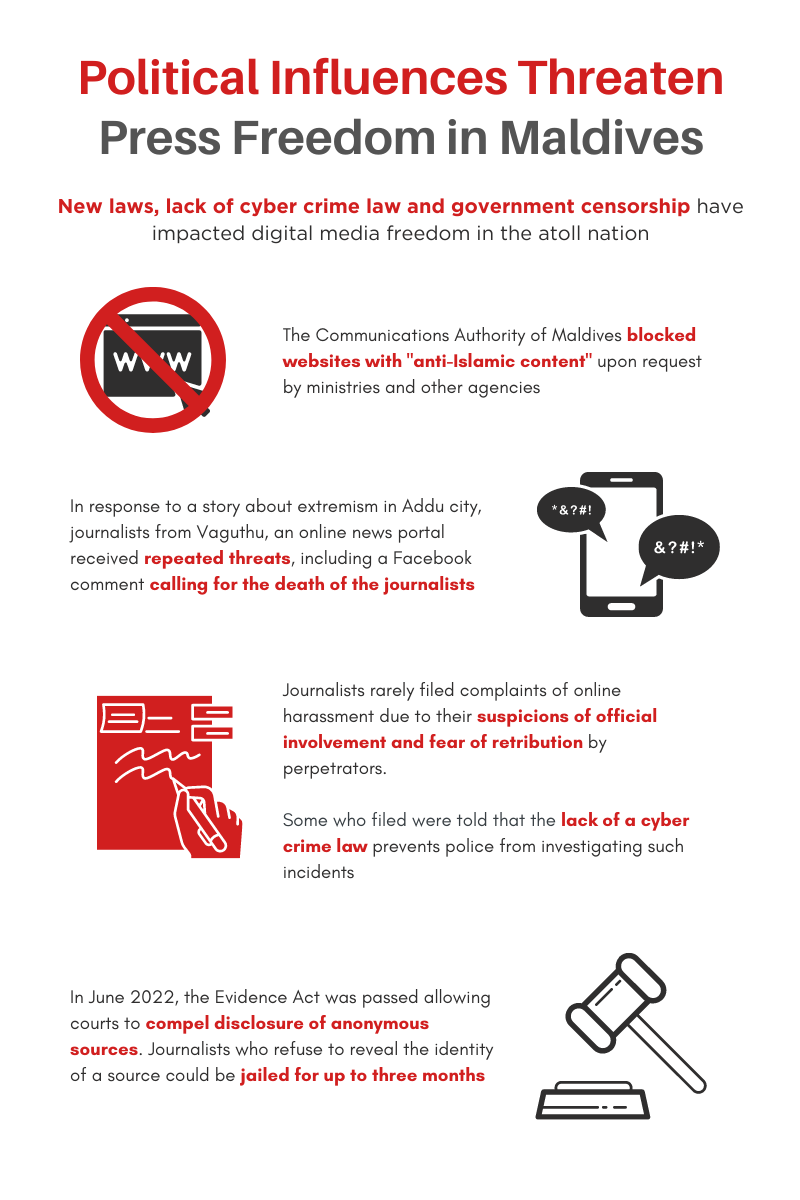

As the 2008 Maldives constitution outlaws speech “contrary to any tenet of Islam”, the country maintains reservations to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights’ article 18 on freedom of thought, conscience and religion. The Communications Authority of Maldives – which does not proactively monitor internet content – regularly blocks websites with anti-Islamic content upon request by ministries and other agencies, a power that is wielded on political direction in contravention of international standards. Details of blacklisted sites are not made public. But internet access is otherwise unrestricted and online content is not censored.

Nonetheless, the fear of being labelled “secularist” or “anti-Islamic” prompts journalists and editors to practice self-censorship. A reminder of the danger came in February 2023 as a comment posted on Facebook called for the death of Vaguthu journalists. The threat came in response to articles about extremism in Addu City. Vaguthu journalists faced repeated threats in the wake of their reporting. A case was lodged with the police amid concern over the failure to properly investigate such threats and bring perpetrators to justice.

Some journalists who reported online harassment were told that the lack of a cyber-crime law prevents police from investigating incidents. In one instance, a journalist who filed a case of harassment from phone calls was allegedly asked by the police if she wished to withdraw the complaint. “I didn’t withdraw it, but even months later the police didn’t share any information about the investigation’s progress with me,” she recalled.

“Due to their suspicions of direct or indirect official involvement and fear of retribution by perpetrators, journalists rarely filed complaints of online harassment with authorities,” according to the 2021 Maldives Human Rights Report by the U.S. State Department.

Gender in the newsroom

In a male-dominated workplace, women journalists in particular suffer from the consequences of impunity. In two high-profile cases of sexual harassment in 2020, neither of the alleged perpetrators – Avas Online’s veteran editor and the former communications secretary at the president’s office – faced any charges.

In October 2022, Mohamed Shafiu, a member of the Maldives Media Council (MMC), was accused of repeatedly messaging and harassing a Vaguthu journalist with questions about her private life. The unsolicited messages were allegedly sent after he accompanied a group of journalists including her on a training trip to India organised by the MMC. Shafiu – who denied any wrongdoing – was relieved of official duties pending an inquiry. But the suspension was soon lifted after the police dropped the case over “lack of evidence”.

More than a quarter of women journalists have faced sexual harassment, according to a report on gender equality in the media published by the Maldives Journalists Association. The findings of the report released in December 2022 paint a mixed picture.

Women accounted for about 30 per cent of staff in mainstream outlets with a very low proportion in leadership roles. But paid maternity leave was near universal, said the report, and some new mothers were offered flexible working options. There were several female editors and heads of newsrooms, including women in charge of two television stations. But the odds remain stacked against them. The employment law grants a 60-day maternity leave but women who take longer leave to start a family are at a disadvantage when it comes to career advancement.

In June 2022, three suspects were arrested in connection with the abduction of journalist Ahmed Rilwan. The arrests came after a breakthrough by the presidential commission on deaths and disappearances.

The Communications Authority of Maldives – which does not proactively monitor internet content – regularly blocks websites with anti-Islamic content upon request by ministries and other agencies, a power that is wielded on political direction in contravention of international standards.

Members of the MJA and Maldives Media Council express concerns over the proposed Evidence Act in the Judiciary Committee of the Parliament. Credit: Maldives Parliament

Source disclosure

On June 30, 2022, the Evidence Act was passed with provisions that allow courts to compel disclosure of anonymous sources. Notwithstanding a constitutional right to protect sources of information, the law introduced exceptions in cases involving acts of terrorism or offences related to national security. According to the ambiguous criteria, a court could order disclosure if it decides that there would be no negative impact either to the source or to the ability of journalists to find sources. Journalists who refuse to reveal the identity of a source could be found in contempt and jailed for up to three months.

Concerns shared by the Maldives Journalists Association (MJA) and the media council went unheeded when parliament reviewed the government-sponsored legislation. Members of the MJA and the Editors Guild protested outside parliament as the Evidence Act was voted through. Their fears included potential abuse of the “overly broad” provisions to force journalists to disclose sources. The MJA warned of “a chilling effect on freedom of expression” even in the absence of enforcement in court or imprisonment of journalists. “Just the fear of being exposed – especially sources used by reporters to uncover corruption and abuse of power – is enough for these sources of information to dry up,” it explained.

A petition signed by 158 journalists calling for revisions before ratification was submitted to the offices of the president and attorney general. But the president signed the bill into law on July 18, 2022.

Following consultations with media rights organisations, the government proposed amendments in September 2022 to more clearly specify terrorism and national security-related offences and to determine factors that must be considered by a judge. The power to order disclosure was limited to the High Court. The MJA welcomed the proposed changes but opposed the exception for offences related to national security, “as there is a possibility of misusing the term in the absence of a law defining national security offences in the Maldives.”

The police’s summoning of a journalist on July 21, 2022, underscored the need for source protection. Ahmed Azaan, co-founder of pro-opposition Dhiyares, was questioned about alleged unauthorised access to a government hospital’s patient portal. In February 2022, citing an unnamed source, Azaan reported on a bug in the online database that allows anyone to access confidential health records. The police insisted that the summons was unrelated to his work as a reporter, accusing Azaan of leaking health information about senior government officials. He denied the allegations.

Media oversight

Regulatory bodies remain susceptible to government control through political appointees, who are nominated by the president and approved by parliament. The seven members of the Maldives Broadcasting Commission, which accredits journalists and regulates television and radio stations, can be dismissed and replaced at will when the president’s party has a parliamentary majority.

In contrast, eight of the 15 members of the Maldives Media Council (MMC) – which regulates print and online media – are elected by media organisations. A serious electoral flaw was remedied in October 2022 when inactive media outlets and publications registered by government agencies were barred from voting. In the past, “shell media companies” that did not regularly publish were able to influence the council’s composition.

Following the MMC’s most recent election in December 2022, the MJA expressed concern over the election of an official from the state broadcaster Public Service Media (PSM) as the council’s new president. Since members of the PSM’s board of directors are directly appointed by the president, a representative of state media chairing the oversight body “upends the existing system of media self-regulation and opens it to undue influence,” the MJA warned.

Members of the MJA and the Editors Guild protested outside parliament as the Evidence Act was voted through. Their fears included potential abuse of the “overly broad” provisions to force journalists to disclose sources.

Regulatory bodies remain susceptible to government control through political appointees, who are nominated by the president and approved by parliament.

The newly-elected Maldives Journalists Association (MJA) Executive Committee members pose for a photo in September 2022. The MJA have been an important voice for advocacy and media rights since its revival in 2020. Credit: MJA

Workers unite

During an evaluation mission in August 2022, the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) discovered a “widespread industry practice of ‘docking’ journalists’ salaries by media companies when journalists were deemed to be underperforming or not filing a set number of stories per day.” Some journalists also worked without an employment contract. The IFJ identified a “vital need for worker rights to be protected which can only happen by strengthening the labour rights framework.”

The IFJ’s local affiliate, the MJA, was revived in September 2020 after a six-year hiatus, during which the media community lacked a collective voice. In July 2022, the NGO amended its statutes after a nearly two-year review and consultation process, introducing measures to promote women’s participation, improve fiscal transparency and strengthen democratic governance and accountability.

The MJA signed a partnership agreement with the local chapter of Transparency International in October 2022 for collaboration in capacity building for journalists, organisational development, research and advocacy, and resource sharing. In August, the MJA decided to become a member of the Maldivian Trade Union Congress (MTUC), which represents more than 10,000 workers.

On March 3, 2023, speaking at the MTUC’s Workers’ Congress, President Solih pledged to submit an industrial relations bill to parliament. The long-awaited law would pave the way for collective bargaining and the formal registration and functioning of workers’ unions for the first time. Other overdue laws in the pipeline include legislation on privacy and data protection.

As with existing laws that guarantee safety, gender equality and other constitutional rights, effective implementation is key to addressing labour rights violations. With necessary legal safeguards in place, political will coupled with the goodwill of media management could steer journalism in the Maldives on the path to maturity, professionalism and independence.