NEPAL

A Watchful Election Year

Children play in a chariot under construction for the Bisla Jatra, which begins the new year on April 6, 2023. Over the last year, Nepal’s media faced many of the same problems, with payment disputes still present for media workers and at least 55 media rights violations recorded across the country. Credit: Amit Machamasi / NurPhoto via AFP

Nepal witnessed yet another year of political upheaval with journalists continuing to face all the old problems as the nation emerged from the Covid pandemic. Journalists and unions continued their struggle for labour and media rights while also pushing governments toward press freedom-friendly laws and regulations. Added to the continuing threats and attacks on journalists were digital attacks and attempts to demean journalism and journalists by political leaders. As Nepal held two elections during the year, journalists also faced increased restrictions.

It was a politically charged year due to polls. Nepal held its Local Level Elections on May 13, 2022, in six metropolitan cities, 11 sub-metropolitan cities, 276 municipalities and 460 rural municipalities, and the general elections for federal and provincial parliaments on November 20, 2022. In the general elections, the Nepali Congress emerged as the largest party winning 89 seats in 275-member House of Representatives while CPN-UML was second with 78 seats and the Maoist party won 32 seats. The surprising outcome was the Rastriya Swotantra Party (RSP), formed six months before the general election by former journalist Rabi Lamichhane which won 20 seats to become the fourth-largest party (subsequently, Lamichhane lost his seat and other formal positions following the Supreme Court verdict on his citizenship case.)

After the general elections, Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba failed to hold together the pre-election coalition with the Maoists thus losing his premiership to Pushpa Kamal Dahal ‘Prachanda’ who garnered support from UML and RSP among others to form a new alliance. The alliance didn’t last long but Prachanda returned to the old alliance with Nepal Congress and others to continue as the Prime Minister and won a vote of confidence in the Parliament for the second time within the first three months of 2023.

Demeaning the media

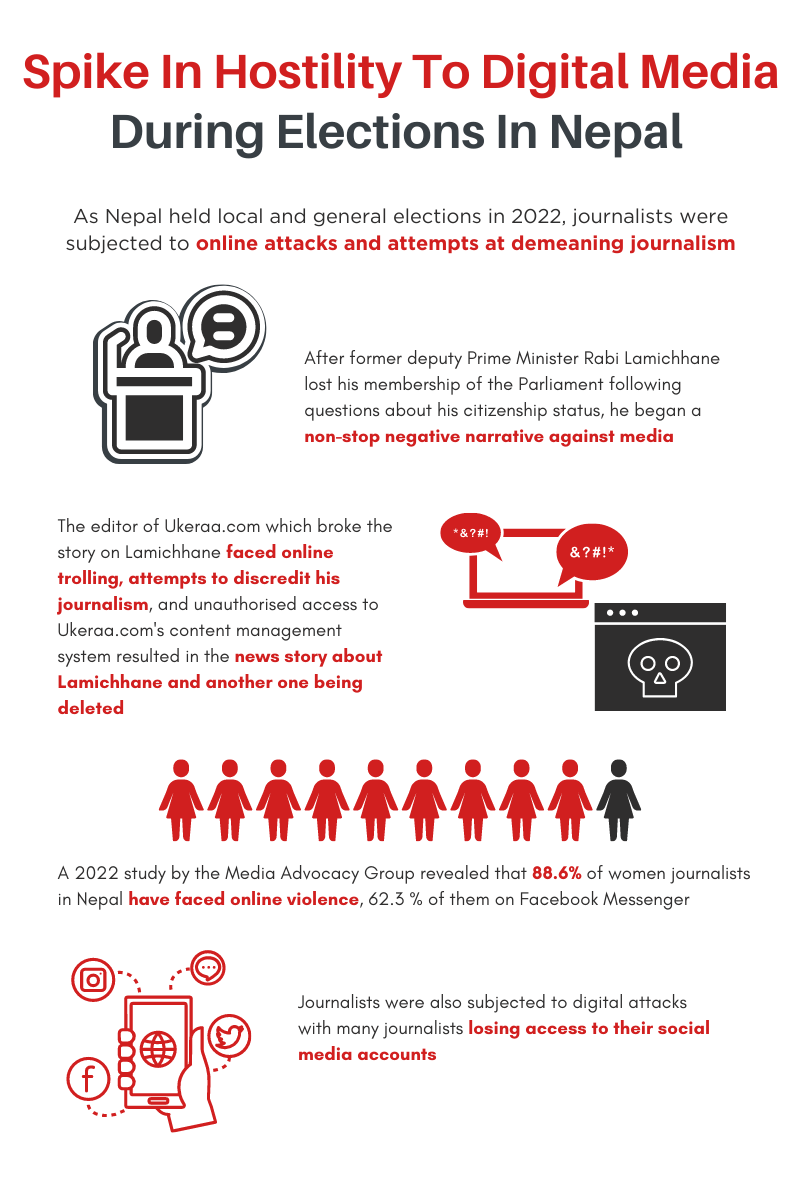

Journalist-turned-politician Lamichhane become the Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister in the government formed after the election. He lost membership of Parliament and resigned from the government after the Supreme Court decided he had not followed due process to re-obtain Nepali citizenship thereby nullifying his election victory. He re-obtained citizenship within a couple of days and organised a press conference on February 5, 2023, during which he named a few media and a dozen editors for collectively targeting him and accused them of publishing misinformation. Most of the media and journalists – through official or personal channels – refuted his accusations and challenged him to prove them wrong. Nevertheless, his accusations prompted a non-stop smear campaign against the media by cadres of his party and his supporters.

Lamichhane was not alone in running down the media. Newly elected Speaker of the House Devraj Ghimire met a delegation of the Federation of Nepali Journalists (FNJ). After the FNJ delegation briefed him, Ghimire claimed that journalists were on sale and that yellow journalism was increasing at an alarming rate. His statement drew flak from media and rights advocates, and he subsequently retracted his ‘accidental comment’ and restated his commitment to the freedom of press and expression.

Similarly in July 2022, Provincial Minister of Internal Affairs and Law Kedar Karki threatened journalists during an interview after critical news about misuse of the budget was published. He threated journalists saying he could frame journalists for rape.

Media Rights Violations

Killings

Arrests

Nepal’s president elect Ram Chandra Paudel arrives at the Federal Parliament in Kathmandu on March 9, 2023. Nepal held provincial and national elections in 2022, with political discourse and state restrictions impacting press freedom throughout the year. Credit: Sanjit Pariyar / NurPhoto via AFP

The surprising outcome was the Rastriya Swotantra Party (RSP), formed six months before the general election by former journalist Rabi Lamichhane which won 20 seats to become the fourth-largest party.

Online attacks and digital threats

Online attacks against journalists were at a high during the tenure of Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli. He urged the supporters to attack “like wasps” all critics the government. IT cell members then started attacking journalists critical of the government. Some of the IT cell members were later publicly known for their journalist bashing. Alongside, Oli’s close aide Gokul Prasad Banskota, the then-minister of communications and information technology brought in several bills in parliament which are harmful for press freedom.

Online portals were often at the frontline of reporting, a phenomenon that has prompted attempts to control them. In fact, Lamichhane’s citizenship was first questioned by an online media portal. Ukeraa.com’s editor KP Dhungana relentlessly followed the issue, unearthing proof. He was targeted by trolls and attempts were made to discredit his journalism by Lamichhane’s supporters. The trolling against Dhungana and his work continued for months. Although Lamichhane made no comment on it initially, during a February 5, 2023, news conference he admitted that it was good journalism.

Women journalists in Nepal are particularly prone to being abused online. A study by the Media Advocacy Group released in December 2022 revealed that “an overwhelming majority” or 89 per cent of women journalists in Nepal have faced online violence. Disturbingly, 53 per cent faced violence perpetrated by their own colleagues in the media. According to the study, the most common platform for online abuse was Facebook Messenger: 62.3 per cent respondents reported facing online violence on Messenger, while 15.3 per cent faced such abuse on Twitter, 12.8 per cent on WhatsApp, 11.7 per cent on Viber, 6 per cent on email and 4.6 per cent on Instagram.

Significantly, lack of redress can be correlated with the reluctance of the police to investigate the complaints. Participants in the study said that the cyber bureau of the Nepal Police was reluctant to register cases due to a lack of clear and specific laws to address such online violence.

In December 2022, a few weeks after the report about Lamichhane was published, the news about him and another critical report about the son of the vice-president was replaced by irrelevant content by some unknown people who had hacked into the news portal’s content management system.

Co-ordinated online attacks on media and journalists were on rise during the year. Media and ‘the dozen editors’ accused by Lamichhane faced trolling on social media. An example of coordinated online discrediting was seen in May 2022 before the local level elections, when OnlineKhabar.com – one of the most popular online news portals of Nepal – published an op-ed on Balendra Shah, the independent mayoral candidate of Kathmandu Metropolitan. Popularly known as Balen, the singer-turned-politician was using the national flag during his election campaign and the op-ed questioned whether such use was in accordance with the law. Supporters of Balen, who went on to win the election and become the capital’s mayor, called for a boycott of the news portal and campaigned to ‘unlike’ its Facebook page. The portal lost thousands of ‘likes’ within days. OnlineKhabar.com to prove that they were not anti-Balen, posted links to old news reports that portrayed him positively.

Journalists were also subjected to digital attacks with many journalists reporting that they lost access to their social media accounts. A case that was widely reported was that of senior editor Kishore Nepal, who said he gradually lost access to his social media and email accounts. He went to the police, but the police did not investigate properly, he claimed.

Struggle for wages

Non-payment of wages has been a long-standing issue in Nepal’s media sector – and an issue that journalist unions have always been dealing with. The FNJ, which has a system of complaints and takes union actions, received more than 64 complaints in the last year and a half. Journalists working in mainstream media have filed complaints and FNJ organised protests and sit-ins, and many of these actions resulted in agreement with the management. Some of these agreements were not implemented, forcing journalists to resort to protests again.

According to FNJ data, more than ten journalists working in Image Channel television, Nagarik daily, Rajdhani Daily, Annapurna Post daily, Nice TV, Janata TV, Galaxy 4K TV, state-owned Gorkhapatra daily and National News Agency, and Kantipur television have filed complaints related to labour rights, especially wages.

An example is that of journalist Dipa Dahal, who was handpicked by Kantipur TV while she was working with an online media portal. She said that while offering her the job, the chief editor of the channel asked for a minimum two-year commitment. With more than a decade of experience in journalism, Dahal joined Kantipur TV and was given an initial contract of six-months. Two months before its expiry, she was told by the Human Resource department that her contract would not be renewed. She wrote in an article that it was surprising, because she was always praised for her work in the newsroom meetings and had performed all her duties without facing any complaint from the editor. She claimed that she was unlawfully and unprofessionally treated because of her conflict with someone in the human resources department more than a decade ago. She filed a complaint to FNJ. After going public, and journalists standing in solidarity with her, Kantipur TV reinstated her and paid her a compensation. This victory is significant, in a scenario where there are only 2,408 women journalists of the total 13,077 registered with the FNJ.

Non-payment of pending wages is a big issue. In first few months of 2023, the media sector saw an order by the Labour Court to freeze all accounts of Kantipur Media Group, the biggest publication house while deciding on a case filed by staffer Yadu Prasad Pokharel and three others. Police arrested the owner of Nice TV after the cheques he gave to the journalists bounced and later released him after he committed to pay up within a few days.

A study by the Media Advocacy Group released in December 2022 revealed that “an overwhelming majority” or 89 per cent of women journalists in Nepal have faced online violence.

Former television host and Independent Party’s candidate in Nepal’s general election, Rabi Lamichhane, speaks in an interview with AFP in Padampur. As Nepal held two elections during the year, the media industry faced increased restrictions to freedom of the media. Credit: Prakash Mathema / AFP

Corporate control

Given the precarious economy still struggling with the Covid effect, the role of big business in media ownership and functioning is a growing concern. Inevitably, certain corporate houses are dangerous to freedom of the press. Any coverage perceived as “negative” could lead to a blockade of advertisements and thus affect the very survival of the media. When Nepali daily Nagarik published a news report about NCell, Nepal’s largest private telecom service provider, advertisements stopped. Other newspapers went on to condemn Nagarik’s news report. With threats of withholding advertising revenue, media outlets practice a self-censorship of sorts by refraining from reporting on the doings of corporate houses.

Attacks and threats

The FNJ has recorded 56 cases of press freedom violations since May 3, 2022. Although the number of physical attacks and violations has diminished, there are still concerning trends and incidents. According to record, 25 cases of misconduct with journalists were recorded in the period while 14 incidents of physical attacks and 13 incidents of threats were recorded.

Kantipur daily’s journalist in Saptari, Abdesh Kumar Jha faced threats on social media after publication of a news report in September 2022. His photo with a cross was shared on social media in Facebook indicating that he would be killed. A team of journalists filed a complaint with the police, but the police remained inactive although the Facebook IDs of those posting the photos were included in the complaint.

Similarly in September 2022, journalist Binu Subedi was threatened with physical attack by the chairperson of the CPN-UML student union Sunita Baral. Retweeting a comment by a union cadre that said, ‘Binu Subedi will someday be badly beaten’, Baral added a comment: ‘Looks like it’s needed.’

During the Local Level Elections in May 2022, many journalists faced misconduct by election officials or security agencies while covering the elections. Many journalists were denied entry to voting booths and the vote count area, while some were given entry without permission for a camera or mobile phone. Although there were no major events of violation, there were sporadic incidents all around the nation with journalists’ rights not respected.

These are just a few examples of what Nepali journalists are facing. While many of the threats on journalists were issued by political leaders and most of the attacks were carried out by unknown groups, there were also incidents where state agencies meant to protect journalists misbehaved with journalists. In most such cases, the perpetrators remain unpunished.

Nepal’s media content regulator – the Press Council of Nepal – faces criticism for being politically motivated. It was evident in at least one case in October 2022 when it issued a 24-hour clarification notice to Nagarik daily for publishing a satirical cartoon on the former Prime Minister and CPN-UML chair KP Sharma Oli. The Council’s move was called a ‘politically motivated statement and against the constitutional rights’ by Freedom Forum Nepal.

Misinformation and elections

Misinformation is already hurting the public trust of citizens in media as many of them are not able to differentiate between journalistically produced content, blogs, social media posts, television reports or YouTube videos. During the elections, some misinformation was produced to mimic news reports. There were fake screenshots of online media or fake frontpages of newspaper circulated. They contained news the media hadn’t published.

Although misinformation did not have a significant impact on the outcome or the integrity of the elections, as concluded by a report on misinformation monitoring from the Center for Media Research, Nepal, there was a sizable number of instances of misinformation. The emerging trends are likely to threaten public trust in the media in future.

The FNJ during the elections also issued a statement urging media to follow the code of conduct while covering elections indicating that some media reports were questionable. Over the last few years, some YouTube videos were promoted as news but have been either misinformation or exaggerated versions of news. While some of the YouTube channels have formed an association and committed themselves to follow self-imposed ethical guidelines, many channels continue to produce content lacking in credibility. This prompted the Press Council of Nepal, the media content regulatory body, to recommend action against 34 YouTube channels in July 2022 for violating the code of conduct. The Council claimed that it recommended action against the YouTube channels because they were responsible for incitement, spreading misleading information and fake news, disrupting social harmony, and disseminating information that strains international goodwill and brotherhood among countries.

The Election Commission created a ‘Press Office’ to monitor media and social media during the elections. However, the decision to include representatives of the Nepal Army and Nepal Police drew criticism with the FNJ stating that it was an attempt to restrict citizens’ right to free expression. When the Press Council of Nepal already existed to monitor media content, the formation of a unit by the Election Commission was seen as overreach. There were incidents during the elections when the Commission issued ‘press freedom violating directives’ directly to the media.

One example involved Nepali news portal Setopati.com. On November 5, the Commission ordered the portal to delete an article within 24 hours, deeming the story defamatory and violative of the electoral code of conduct. On November 4, Setopati had published news that Nishan Kharel, the son of former law minister and election candidate Agni Kharel, had retained Nepali citizenship and voting rights in Nepal despite active service in the United States Army. Setopati published a special editorial criticising the demand to take down the story, stood by its story as ethical and fact-based and refused to delete it. The Commission’s move invited criticism from media and media rights organisations. The Commission rescinded its order on November 7.

During the elections, some misinformation was produced to mimic news reports. There were fake screenshots of online media or fake frontpages of newspaper circulated.

While some of the YouTube channels have formed an association and committed themselves to follow self-imposed ethical guidelines, many channels continue to produce content lacking in credibility.

Police stand guard near ballot boxes as polling stations close during the general election in Kathmandu on November 20, 2022. The decision to include police and army representatives in official election fact-checking mechanisms was met with criticism from journalists and their representative groups. Credit: Prakash Mathema / AFP

Overstep and intrusion

The Constitution of Nepal 2015 guarantees “complete press freedom” in the preamble as well as ensuring press freedom, and freedom of expression and opinion as fundamental rights. However, the government has not been able to promulgate new press laws to effectively implement these constitutional rights.

Instead, the proposed laws have restrictive provisions that impinge on civil liberties. A recent example is a controversial bill to amend and unify various telecommunication laws. The bill has a provision that will allow the government to tap the phones and social media accounts of anyone without prior court approval. A similar bill was presented in Parliament a couple of years ago.

Section 77 (1) of the new bill states that the investigative body can record calls of anyone or get the details disclosing the identity or other details from the service provider if the person in question is believed to be engaged in activities against Nepal’s sovereignty, territorial integrity, national interest, treason, organised crime or criminal offence.

Section 79 states that an investigating officer can also deactivate a telephone, mobile or communication media. IFJ affiliate Nepal Press Union, protested the bill, stating that it restricts constitutional provision of rights to privacy and freedom of expression.

Many provincial and local level governments have implemented media laws that are restrictive and overreaching in many cases. A common trend in those laws, as well as in the draft bills of federal laws, are provisions allowing the provincial or local level governments to annul broadcasting licenses, suspend broadcasting, overreaching and vague definitions of reasonable restrictions of press freedom, the authority to direct broadcasting or stop broadcasting of certain materials, and punishments. Researchers and advocates have pointed out many provisions of the laws at the provincial and local level that are contrary to the constitution and press freedom.

Constant vigilance

Nepal entered 2023 with a new government and several laws needing to be promulgated. But early indications, based on what people in authority have expressed, as well as the state of press freedom violations, show that the new as well as older restrictive draft bills, cannot guarantee press freedom. The number of incidents of press freedom violations might have come down, the overall press freedom ranking may have improved, but the fight for press freedom and civil rights will continue in the coming year. The IFJ affiliates – the FNJ and the NPU – will have to continue to be ever vigilant and sharpen monitoring and advocacy work to ensure that the situation doesn’t deteriorate. A watchful eye must be kept on the new laws to ensure that they are not restrictive at a time when the mass media and journalists are fighting against misinformation and struggling with digital transformation. The year ahead doesn’t seem easy for Nepal’s journalists.

Members of the Federation of Nepali Journalists meet with Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal in January 2023. Credit: FNJ