IFJ-SAMSN Kashmir Campaign 2020

Access Denied

Access Denied

An introduction into the world longest communications shutdown. #JournalismMatters #KeepItOn

It has been 245 days since the start of the complete communications blockade in the Kashmir Valley. As the world goes increasingly online in an every tightening lockdown and stringent physical distancing to combat the deadly novel coronavirus or COVID19 sweeping across the globe, a glimpse into the world’s longest Internet shutdown in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) might offer some lessons in adversity and innovation, led by Kashmiri journalists.

This extraordinary internet shutdown began on the night of August 4, 2019, on the eve of the abrogation of Article 370 of the Constitution of India which granted special status to the state of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). The days before this momentous step were marked by unease and suspicion triggered by thousands of security forces being marched into the Kashmir Valley, already one of the most militarized zones in the world. Rumours of cross-border clashes and terror strikes were rife, and verifiable facts were few on the ground. On the morning of August 5, the few that had access to dish TV watched in shock the proceedings of the Indian Parliament which not only abrogated the special status of J&K and stripped it of even its limited autonomy, but also rendered inoperative Article 35(A) which allowed the State Assembly to define ‘permanent residents’ and confer upon them certain rights, including that of land ownership and access to government jobs. The same day saw the downgrading of the state of J&K into two union territories: Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh.

Why we are campaigning for Kashmir’s media?

When the Indian government imposed the internet shutdown in Kashmir on August 5, 2019 revoking Article 370 of the Constitution of India, journalists in Kashmir struggled with their work and lives. The problems they faced were numerous; ranging from not being able to gather information or to write, publish, print or broadcast news, ultimately leading to job losses and salary cuts, in addition to harassment, controls on movement and the necessity to file stories from a designated media centre.

In January, India’s Supreme Court ordered the government to review all restrictions in Indian-administered Kashmir within a week, saying the indefinite suspension of people’s rights amounted to an abuse of power. While some communications have been gradually restored, the block on high speed mobile 4G internet in Kashmir still remains in place. On April 3, this ban was again extended to April 15. This continues to deny more than seven million people living in Kashmir to access reliable health information about COVID-19 in a situation where every day counts.

April 5 marks 245 days – eight months – since the initial shutdown began in Kashmir. Even before some communications were restored, the blockout was already the world’s longest communication shutdown in a democracy. India continues to lead the world in the number of shutdowns enforced on its people.

Kashmir: Access Denied

Eight months after the switches were turned off on August 4, 2019, Moazum Mohammad provides an intimate glimpse into the world’s longest communication blockade.

Rumours flew thick and fast, triggering widespread anxiety in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) during a sweltering week at the end of July 2019, when the Kashmir Valley was witnessing a relatively peaceful summer. But the whisper network, rife with rumours about impending doom was active in personal networks and the ubiquitous social media. It triggered wild guesses and speculation, ranging from possibilities of war between the two South Asian nuclear-armed rivals India and Pakistan to a possible massive offensive against militants in the conflict-torn Kashmir Valley. This put the entire Valley on edge as residents resorted to panic buying to stock up on basic staples, baby food and medicine. There was a five-fold increase in sale of fuel as snaky lines of vehicles covering almost a kilometre waited patiently for hours to fill their tanks; many collected fuel in jerry cans. Equally, there was no let-up in the long lines outside banks and ATM kiosks.

It was a frenzied atmosphere as worry multiplied with every fresh official order. The clutch of official orders about shipping an additional 100 companies of troops (10,000 personnel) comprising the Central Reserve Police Force and Border Security Force– started doing rounds on social media platforms including WhatsApp, Facebook, Twitter, thereby amplifying panic.

The J&K government’s advisory on August 2 asking Hindu pilgrims visiting the cave-shrine of Amarnath in the mountains of Pirpanjal to leave immediately citing “intelligence inputs of terror threat” in Kashmir caused great alarm. This sudden move came in the face of a more than 30 per cent surge in Hindu pilgrims as more than 350,000 devotees had visited the Amarnath that year amid massive security. Tourists were evicted from hotels in hill stations and bundled into vehicles to return them to their homes.

It spurred panic among the non-local workforce, estimated to be around a million, to leave the Valley. This brought about an abrupt halt to construction and development work, both private and government. Alongside, J&K Governor Satya Pal Malik attempted to dispel rumours by terming the reaction “exaggerated” and asked residents to maintain calm.

But as midnight struck on August 4, everything became clear in black and white as assurances fell flat. Suddenly, phones lines and Internet connections were snapped in the middle of conversations. Amid darkness and silence, people tried in vain to find answers.

The journalist in me tried desperately to make sense of the ominous developments, and I peered out of my window. In the darkness, all I could see were street dogs patrolling the road under fluorescent lights. The wait for dawn was endless as time stood still. It was a long and lonely night.

Apprehensive about my safety, my family tried – unsuccessfully – to dissuade me from leaving home in the morning. Hundreds of thousands of armed forces clutching assault rifles were positioned on all roads, across which they had erected iron barricades and laid razor wires to prevent public movement. Shops were shuttered, markets were closed and transport was off the roads, except for armoured vehicles cruising the streets round the clock. It was a veritable war zone with schools, colleges and universities closed and little access to healthcare.

Amid a sense looming fear, I cautiously walked past several barricades and razor wires with gun-toting uniformed men stopping, frisking and checking identity cards of passers-by. At several places I furtively managed to circumvent checkpoints by walking through interior roads. When I entered the news outlet’s office, there were five or six office staff glued to the television, watching the cluttered screen splashed with announcements about the scrapping of Jammu and Kashmir’s semi-autonomous status and downgrading the erstwhile state into a union territory.

There was a strange feeling in the room as the men, who worked as watchmen, were feeling emotionally distraught watching the region being stripped of its special status. Inside, the newsroom was empty and so were the advertising and marketing departments as staffers were not allowed to move on streets. Even hawkers could not collect and distribute newspapers. A newspaper vendor in south Kashmir’s Shopian later told me that he resumed his work only 20 days after the August 5 shutdown.

I walked back under the noon sun and started moving towards home to make my family aware of the momentous decision that had been taken in New Delhi. Only a small section of the population that was connected to Dish TV was able to watch news channels, since cable TV too had been suspended. On the way, a few people sitting in front of shuttered shopfronts inquisitively asked me the reason for the clampdown. When I entered my neighbourhood, which also houses senior government officers, people walked toward me to hear news about the world outside, as people were barricaded in their homes.

In the evening, the buzz at news offices was missing. Newsrooms were empty, bereft of reporters and editors as stringent restrictions prevented them from venturing out. A few who were able to reach their offices watched news channels and listened to the radio and transcribed the bulletins for the next day’s truncated edition of just four pages. In the morning, there was huge demand for newspapers as people were anxiously waiting for news about the happenings unfolding around them. A hawker outside Srinagar’s Shri Maharaja Hari Singh Hospital was surprised to sell 100 papers within an hour on the morning of August 6. A paper, which costs a mere 3 rupees, was sold for Rs 10 in the face of public thirst for information.

“On August 4, our paper was printed but the next day there was a complete blackout and distribution got disrupted. We did not know if our distributor could distribute the paper. But later we came to know, all the 1500 copies were sold in a day,” says Fahad Shah, editor The Kashmir Walla.

As with the seven million civilians in the Valley, the ban did not spare news organisations and journalists. It had a crippling impact on the entire media community as there was no access to information, news gathering, verifying, research or communicating with sources.

Besides the heavy deployment of troops, mass arrests of more than 5000 people, including three former chief ministers and dozens of legislators, politicians and lawyers caused a sense of foreboding among journalists.

But they were as helpless as rest of the population. The communications blackout spurred apprehensions among journalists when they did not see their colleagues for a day or two. Who knew what fate might have befallen them? There was no way to find out.

Under Pressure

Under Pressure

When a reporter Irfan Malik working with a daily Greater Kashmir from south Kashmir’s Tral was picked from his residence in a midnight raid on August 14, nobody in the media community was aware about his detention until his parents travelled more than 40 kilometres to convey the news to journalists in Srinagar. He was released from custody after journalists lodged a protest with government officials during a presser, but no reason was given for his arrest.

Senior journalist Peerzada Ashiq who reports from Kashmir for The Hindu was summoned by the Jammu and Kashmir police on September 1 to Srinagar’s Kothibagh police station. He was questioned and pressurised to reveal the source of his story about the mass arrests in the Valley. Quoting official documents, he had reported that a total of 3,200 persons including 1500 youth were arrested in the first three weeks of August.

Senior journalist and political commentator Gowhar Geelani was stopped from travelling to Germany at the International airport in New Delhi in August. He was to attend an eight-day programme with Deutsche Welle in Bonn. “The officers at the immigration counter at New Delhi’s Indira Gandhi International Airport did not give any specific reason — neither verbally nor in any written communication. They just said they were following ‘orders from seniors’. The decision to stop me from attending my training programme is also an assault on my right to travel and right to free speech,” said Geelani.

In November, the authorities barricaded entry routes towards one of the Valley’s renowned shrines Hazrat Naqashband Sahib in Srinagar’s downtown area and denied permission to devotees to offer annual traditional mass prayer (Khojje Digar) there. When journalists reached at the spot, a police official held a freelance photojournalist Muzamil Mattoo by his neck and assaulted him.

Reporters Anees Zargar and Azaan Javaid were roughed up on December 7 by the police when they went to a neighbourhood in Srinagar to cover stone-throwing protests. Police and paramilitary forces were deployed around the protest site and as the reporters were leaving, the police snatched their phones and beat them up. The police ordered an inquiry into the assault and the reporters submitted their testimonies, but no action has followed so far.

On March 4, two video journalists Qayoom Khan and Qisar Mir were stopped from carrying out their professional duties in south Kashmir’s Pulwama. Their camera and mobile phones were snatched by a police official and returned only after five hours. The journalists said their work stored in their equipment was erased by the police.

Besides brute force, intimidation and pressure tactics were also used. Basharat Masood Srinagar bureau chief at Indian Express and Hakeem Irfan who reports from Kashmir for the Economic Times were summoned to the counterinsurgency headquarters of the police in Srinagar on November 30. They were grilled by police officials about their stories and asked to divulge their sources. They were also asked how they got the official document about the Internet shutdown in the Valley.

On December 23, Basharat Masood and Safwat Zargar of news website Scroll were stopped by the police at Handwara in Kupwara district of Kashmir, while they were on assignment. They were taken to the office of the Superintendent of Police, Handwara where they were questioned and even accused of increasing provocation through their reporting.

Senior journalist Naseer Ganai, with the Outlook magazine along with journalist Haroon Nabi were summoned to the police’s counterinsurgency headquarters in Srinagar on February 8. They were grilled for reporting a statement issued by the separatist group the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front, on the death anniversaries of their founder Maqbool Bhat and Indian Parliament attack convict Afzal Guru. “I was asked to reveal the email ID from which I had received the statement. My phone and laptop were seized. Seizing a phone at a place where they have all of kinds of technological prowess is a worrying sign. It continues to be on the back of my mind,” said Ganai.

Given the enormous pressure and mindful of their personal safety, journalists have sometimes given up that most precious aspect of their profession: the byline. This is but one of the unfortunate consequences of being a journalist in Kashmir at a time when the local media itself is under siege.

“It is a struggle every day and you don’t get to know about playbacks or queries on your stories unless you physically reach the internet facility. The government’s purpose behind this is to limit information flow and to keep a check. For sure, journalism has taken a hit and is one of the most prominent casualties of the clampdown imposed by the government.”

Anees Zargar, reporter, Newsclick.

“There is fear among reporters. Journalists reporting from a conflict zone live on the razor's edge and are sitting ducks for the state actors as well as non-state actors. A journalist by the very nature of the job cannot please anyone.”

Gowhar Geelani, senior journalist and political commentator.

Assault on independent media

Since its emergence as a force to reckon with in Kashmir about three decades ago, the independent media has had to tread the thin line between survival and compromise, autonomy and financial viability.

In early 2019, the J&K Government tactically mounted pressure on local newspapers by eroding their financial viability. Two English dailies Greater Kashmir and the Kashmir Reader and an Urdu daily Kashmir Uzma were stripped of government advertisements. Since Kashmir is bereft of corporates and major private advertisers, revenue generated from government advertisements forms a major component for sustaining papers. While the ban on advertisements to Greater Kashmir and Kashmir Uzma was lifted after August, the Kashmir Reader continues to be banned from getting government advertisements.

The pressure on media was intensified when the owners and a publisher of prominent publications (Fayaz Kaloo of English daily Greater Kashmir and the Urdu Kashmir Uzma, Haji Mohammad Hayat Bhat of Kashmir Reader and Rashid Makdoomi of Greater Kashmir) were summoned by India’s counter-terror National Investigation Agency for questioning to its headquarters in New Delhi in July for a week. This was preceded by the arrest on June 24, of a 62-year-old editor of Urdu daily Afaaq, Ghulam Jeelani Qadri. He was arrested by the Jammu and Kashmir Police in a midnight raid from his home after returning from the office located in Srinagar’s Press Enclave, which houses offices of majority of newspapers. Qadri, a prominent editor, was falsely shown as absconding in a 28-year-old case registered under Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act. He was granted bail by the court. Likewise, pending cases against editors and owners of publications were excavated post August apparently aimed at sustaining pressure on media. Another editor was surprised when he was told about an old case prompting him to immediately approach a court for bail.

The cumulative effect of these coercive acts in addition to the complete communications ban on August 5 completely throttled an enabling atmosphere for media to operate. Its fallout is reflected in over 100 newspapers published from Srinagar without any variety of news and ground reporting.

“This appears to be a deliberate attempt to muzzle the press in Kashmir. Else, why would they ban the internet, which is our lifeline for newsgathering, research, background or reaching out to sources on messaging applications?”

Ishfaq Tantry, General Secretary, Kashmir Press Club.

The hidden stories

The severe humanitarian crisis emerging out of the communications ban and restriction on public movement, the enormous economic losses, lack of access to medical care and schooling, as well as reports of torture, found little or almost no space in local media. While local media could not tell the biggest story of their careers, journalists working for selected Indian electronic, print and online media, as well as international media reported these issues. Foreign journalists are not allowed to enter the region unless they have permission from the Indian government.

In a letter to the Indian envoy to the United States, Harsh Vardhan Shringla, dated October 24, 2019, US Congressmen raised the issue of allowing free access to both journalists and members of Congress in a letter: “We encourage India to open Jammu and Kashmir to both domestic and foreign journalists, and other international visitors, in the interest of open media and increased communication.”

Faced with criticism, Indian External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar defended denying permission for international journalists to enter Kashmir as their presence could provoke unrest. “I can’t commit to a deadline, but as soon as it is safe, they can go. We don’t want their presence to provoke problems – from people who would take advantage of it to show that there is unrest,” he told Le Monde.

Editions were truncated from 20 pages to 4 pages with prominent newspapers refraining from publishing editorials and opinion pieces. Op-ed pages were filled with health bulletins on diabetes, cholesterol etc. The local publications were completely at the beck and call of the government. Of those newspapers that were not blacklisted for receiving advertisements, entire front pages were splashed with government advertisements pronouncing ‘benefits of abrogating Article 370’. At places, these front pages were stuck on walls to ‘create awareness among people’, who were deeply mourning the loss of the special status.

“Media institutions were quite vibrant in Kashmir until the abrogation of August 5. But since then, they have been throttled. We may have to work collectively and it may take some time to fill the gap. Newspapers in Srinagar were published without edit pages, comment sections were missing and papers were reduced to mockery. The reports published were sketchy, briefly giving a one-sided story. There was a sense of fear as media persons had to operate from media centre. That was a major concern for us as we couldn’t reduce Kashmir Times to a pamphlet.”

Anuradha Bhasin, executive editor, Kashmir Times.

Unkind byte: Impact on digital media

Fledgling news websites functioning out of Kashmir were forced to completely suspend their operations as the region reeled under an Internet blackout with no end date. This led to a loss of revenue and drastically dipped their online rankings. Many journalists, especially those working in digital portals of their newspapers lost their jobs and their salaries reduced by local publications. To cite an example, Greater Kashmir, Rising Kashmir and Kashmir Reader were among the prominent local papers which laid off staff and also reduced salaries of journalists working amid this frustrating situation. Salary cuts ranging from 20 to 40 per cent were arbitrarily made across the board.

The Kashmir Walla, freepresskashmir, thekashmirpress suspended their operations for months together as the region reeled under Internet shutdown. While The Kashmir Walla, which has both a print as well online presence, missed publishing two weekly print editions in August and resumed publication in third week of August, the rest have not resumed operations till date.

Wasim Khalid, editor of thekashmirpress, which was launched in May 2018, says that he will start resuming his news website in the coming days as broadband and low speed mobile Internet has resumed. He rued that the last seven months shattered his business plans and delayed pending payments.

“When people can’t access and read it, why run the website? How would we have updated websites? I would have had to travel 10 km to reach the media centre and update website,” he said. After seven months, when the broadband Internet and social media ban was lifted on March 4, he could not even remember the passwords of his social media handles to get them reactivated.

His counterpart, Fahad Shah, editor of The Kashmir Walla has a team of 14 people including a graphic designer, marketing staff and administration. The publication started a weekly edition (print) in June 2019 and though they missed two editions in August, publication resumed in the third week of August and the website resumed after mobile Internet 2G services were restored on January 25.

“If we look at losses incurred in these months, we lost almost Rs 20 lakh for advertisements alone. We did not lay off staff members. We resorted to salary cuts decided by the entire team based on consensus. The team was supportive and it was a democratic decision,” says Shah.

“It took us back several years. What we built in the past year got wasted. Finances, revenue, advertisements, audience vanished. Our ranking has gone. We are quite behind and SEO faced problems and now stories are not appearing in peoples feed. It wasted not just six months but more than that. It will take a lot of time to build an audience now.”

Fahad Shah, editor, The Kashmir Walla.

Reporting from a zone of silence

Initially, many newspapers could not publish their editions and a few who published had to do a herculean task by watching news channels or listening to radio stations for hours and transcribing the news for the papers next day. Newsgathering was almost impossible as reporters, editors and other staff were unable to reach or contact their offices.

When history was made by removing the semi-autonomous status of J&K, local journalists were left idle. The communications ban and massive military crackdown left them without work. There were no movement or curfew passes for media persons and they had to struggle by navigating and circumventing the streets under the control of armed forces as Kashmir was virtually turned into a garrison. But an army of journalists mainly associated with news channels from outside Kashmir was given free access to every part of the city.

Just outside Srinagar’s Rajbagh police station, I encountered a woman reporter working with an Indian news channel showing “normalcy” by claiming that there were no protests and killings. This was emulated by almost all news channels who played out the government’s normalcy narrative instead of questioning the unprecedented clampdown and crackdown.

When the media facilitation centre was established, it was largely meant to facilitate reporters who had come from outside the Valley. They were moving in and around Srinagar in hired cabs seemingly with the sole purpose of lapping up the government narrative. When a massive rally estimating 10,000 people chanting slogans and carrying anti-abrogation flags and Pakistan flags moved from Soura through the streets of Srinagar in the afternoon of August 9, government forces stopped it on way by firing live ammunition and teargas shells. The Government of India’s home ministry denied the BBC and Reuters reports calling them “fabricated and incorrect” and many social media netizens including journalists in India sided with the government. But the BBC stood by its reportage.

Even when this was happening, many media outlets including state-owned Prasar Bharati news service, Doordarshan News apart from few others were unquestionably bolstering the government narrative by showing people offering Friday prayers and queuing up outside ATMs. As reported by Indian magazine Caravan, four of the largest circulating English-language dailies—the Times of India, the Hindustan Times, The Hindu and the Indian Express —either did not cover the incident, or drastically played down its importance. “The Hindu, on 10 August, mentioned the incident in a small story headlined, “Friday prayers are peaceful.” Another report, on the front page, at least twice as long, had Kashmiris lining up in queues to make a phone call, in which the reporter saw “tears of both anger and relief.” The Indian Express used a government statement chiding Pakistan as the lead headline of its front page, which also had a story about the struggle of ailing Kashmiris trying to access government hospitals.

Ground reports of local journalists travelled amid the blackout through various innovative means. Journalists would travel to Srinagar airport and plead with flyers to carry the USB drives and would give them numbers of the concerned persons in Delhi. From then onwards, they would not know whether or not their despatches were published. It was a risk. A few, like young reporter Saqib Mugloo travelled 200 km from Srinagar to reach Kargil in Ladakh where broadband Internet was functioning and sent their despatches from there.

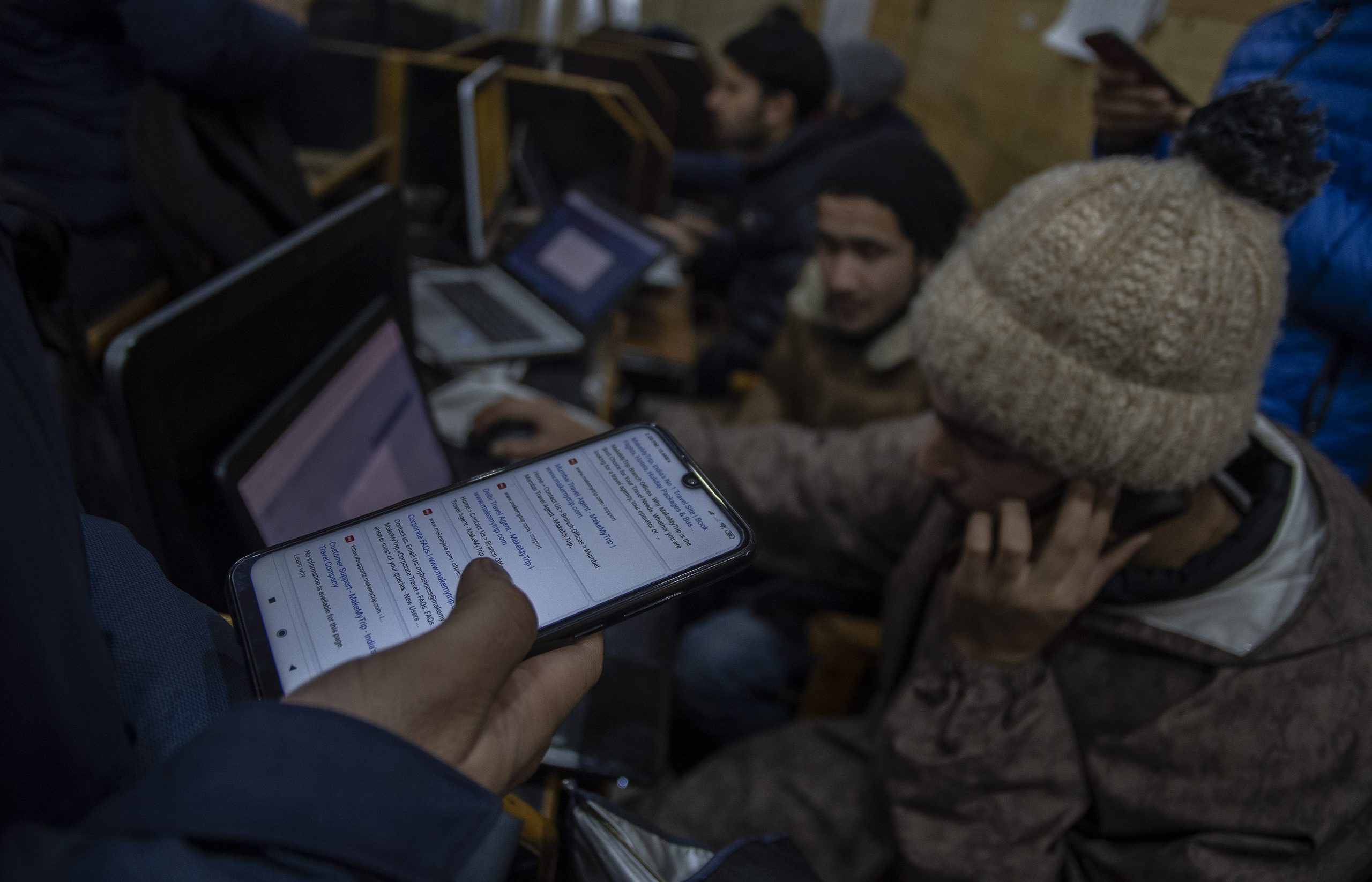

Long queues of people waited outside district magistrates and police stations to call their kin and friends outside the Valley. Emotional scenes were on display after mothers would register the numbers with officials on their turn and then be allowed to talk to their kin in India and abroad. This was a dream come true to get a chance to dial a number. And same was the case with journalists who were given access to a single mobile phone at the media facilitation centre. Journalists wishing to make a phone call had to note down their numbers and other personal particulars including name and organisation and wait for their turn. This was a new normal for more than two months until post-paid mobile phones were restored on October 14.

But it could not end the daily suffering of the media community as Internet was not restored. In both summer as well as in freezing sub-zero temperatures, through rain and snow, journalists had to rush towards the centre for doing their work from sending mails to receiving playbacks or queries from their respective organisations.

It resulted in a loss of opportunity as well because many were unable to access mail in time. Like senior journalist Majid Maqbool says, “By the time, I could respond [to queries from my editor], the story had lost its shelf-life. In fact, it was miracle to get access to mail in time and respond to mails,” he said. Many a journalist said they saw playbacks after their stories were published.

Amid this, the most challenging thing was getting the official version. For more than two months, there was no way to contact officials or verify information. Initially, government officials would address pressers and they were mostly monologues.

“Mobile phones, landlines and Internet were not working. The government was making different claims but there was no way to verify them. There was no way to check background details or do research on the Internet. Going to the media centre means the waste of an entire day as it takes hours to access the Internet there.”

Senior journalist Naseer Ganai.

“In the initial days after August 5, I would send my photos in USB sticks with name and number of a person to contact and hand it over to strangers flying to Delhi from Srinagar. The only mode of communication was trusting a stranger’s face and hope that my photos would reach its destination.”

Photojournalist Umar Ganai.

Life in the ‘sub-jail’

While local journalists were crippled by the clampdown and unable to move, an army of reporters from Indian news channels descended from New Delhi to cover the big story. It seemed as though the government-run media centre was set up mainly to facilitate journalists coming from outside was established at a starred hotel in Srinagar on August 10.

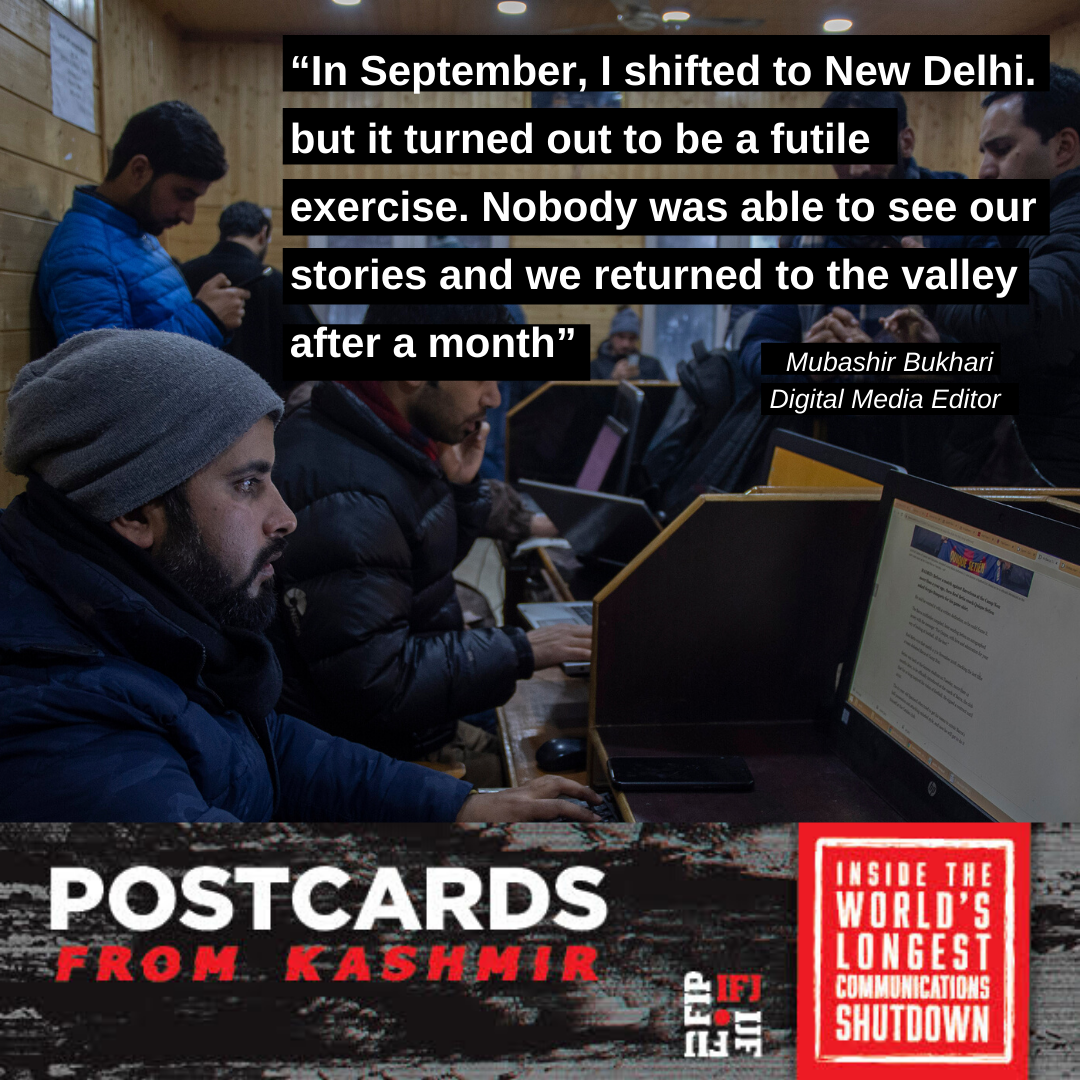

Infamously known among media persons as the ‘sub jail’, the carpeted hall fitted with surveillance cameras became an oasis for hundreds of journalists every day to see each other and access one telephone and slow Internet on four desktop computers. Journalists waited for hours for their turn and at times would remain disappointed due to the long rush and low speed. This harassment and humiliation caused huge distress to entire media fraternity. Three months after, the only change the media community saw was a change in location of media centre from the hotel to the government owned office and additional extension of six more computers apart from wifi connections which was strictly prohibited at the previous place.

“There is no privacy. We access our mails, accounts on public systems and it is risky because it is a government run facility and everything is under vigil. We are living in a stone age and these five months have disturbed our professional as well as personal lives.”

Mubashir Bukhari, digital media editor.

While telephone lines and mobile phones were gradually restored, the Internet shutdown is longest ever in a democracy surpassing the previous record 133 mobile Internet shutdowns in Kashmir in 2016. On October 14, only post-paid mobile phones of 40 lakh subscribers were restored while connections of 25 lakh prepaid mobile users were banned.

Prepaid mobile phone services were restored only on January 18, 2020 allowing journalists to heave a sigh of relief. The government initially ‘whitelisted’ only 153 websites and extended the ban on social media platforms. In the meantime, people were accessing the Internet through Virtual Proxy Networks (VPN) to circumvent the ban, but subsequently, the VPNs too were banned. At many places especially in rural areas, government authorities would check and search mobile phones of people for VPN applications. They were allegations of thrashing if VPN applications were found on phones. To add to the intimidation, the Jammu and Kashmir Police was closely monitoring social media activities and on February 17 filed a case against people under stringent Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), mainly used for militants, for “misuse” of social media users in Kashmir.

On March 4, the government lifted the ban on social media as well as broadband internet.

Legal challenge

Ironically, the Supreme Court of India took five long months to decide on a petition filed on August 10, 2019, by Kashmir Times executive editor Anuradha Bhasin on the Internet ban and restrictions hampering journalists in the Valley. The judgement, however, did not provide any relief to people in Kashmir or to the media as the court did not explicitly order restoration of the Internet. It instead asked the government to review the ban within seven days. Predictably, the government after a review “in the interest of the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of state and for maintaining public order” continued the prolonged ban.

In an order passed on January 10, 2020, the Supreme Court said that an “order suspending Internet services indefinitely is impermissible under the Temporary Suspension of Telecom Services (Public Emergency or Public Service) Rules, 2017”. Any suspension can be “temporary in duration, must adhere to the principle of proportionality, must not extend beyond necessary duration and is subject to review”. Pointing out that the State must produce the orders by which communication was blocked, the apex court said that a review committee must conduct a periodic review within seven days of the previous review, a time frame missing from the existing Suspension Rules.

As per the Supreme Court order: “freedom of speech and expression and the freedom to practice any profession or carry on any trade, business or occupation over the medium of Internet enjoys constitutional protection under Article 19(1)(a) and Article 19(1)(g). The restriction upon such fundamental rights should be in consonance with the mandate under Article 19 (2) and (6) of the Constitution, inclusive of the test of proportionality.”

Following the Supreme Court order, leased-line Internet to tour and travel agencies, hospitals, banks, government offices was restored, but with restrictions, and no social media access was permitted.

Further, four days after the Supreme Court decision, the J&K government restored limited 2G mobile internet in five districts of Jammu and broadband for essential services such as hospitals, banks and government offices. Initially, the government ‘whitelisted’ only 153 websites for access and gradually extended it to 1400 websites till Internet was restored on March 4. But media organisations and journalists were not included in the priority list for allowing Internet access. Later, they were made to sign an undertaking agreeing to six points: there will be no social networking, proxies, VPNs and wifi from the permitted IP; no encrypted file containing any sort of video/photo will be uploaded; MAC binding in place to restrict Internet access to registered devices through single PC; all USB ports will be disabled on the network; the company will be responsible for any kind of breach and misuse of Internet; the company will provide complete access to all its content and infrastructure as and when requested by the security agencies.

“I filed the petition in Supreme Court to challenge the communications ban that affected the media. The court verdict after five months is very significant and will have long term impact. Though immediate relief has not come as it has not ordered restoration of Internet, but the court has asked the government to set up review committee and look into the issue. But the government order restoring internet offers very limited connectivity, which too so far exists only on paper and completely subverts the spirit of the verdict.”

Anuradha Bhasin, executive editor, Kashmir Times.

An ongoing challenge

High-speed 4G internet has not been restored, on April 3, once again the suspension was extended by the Jammu and Kashmir government until April 15. Challenges and risks for journalists have not reduced. In fact, fear looms, as every fresh incident of harassment is reported. Journalists, however, are organising and putting up a resistance despite the pressures. The Kashmir Press Club has responded to the threats and harassment faced by journalists. Besides issuing statements, they staged sit-ins, meetings and seminar to narrate their harrowing experiences. Simultaneously, they engaged with the concerned authorities to throw light on the increasing harassment. Amid this, the last seven months during which journalists faced immense humiliation and harassment has instilled fear, resulting in a self-censorship. Many journalists are reluctant to do stories which might invite trouble by annoying the government. The local media especially has turned quite bland. As a veteran editor repeatedly lamented on the state of local dailies said they are not doing journalism but publishing ishtihaar (advertisements). This is a sorry comment on journalism that was once diverse, vibrant and committed to speaking truth to power. It will take a while before the media in Kashmir recovers from this body blow.

Timeline

- August 4, 2019: A massive internet shutdown is imposed on the eve of abrogation of Article 370 of the Indian Constitution by the Parliament of India. All communication including telecommunications and internet are shut down.

April 3, 2020: The ban on 4G mobile internet is extended till April 15 by the J&K government

Click here for complete timelineBlogs

- Connectivity in times of Coronaby Dr Suhail Naik

News

- Kashmir survived without 4G internet for months, with coronavirus, it really needs it

by Moazum Mohammad in India TodayKashmir in lockdown after autonomy scrapped

by BBC100 days of Internet shutdown

by Asmita Bakshi in Live Mint145 days of internet shutdown in Kashmir, no words on service restoration

by TheHindiIndia’s Supreme Court Orders a Review of Internet Shutdown in Kashmir. But For Now, It Continues

by Billy Perrigo in Time6 months on, IOK still under India’s clampdown

by DawnMedia wants 4G Net restored in J&K to fight COVID-19

by Krishnadas Rajagopal in The HinduResolutions and statements

- South Asia: Media unions and advocates calls for urgent end to Kashmir blockade

South Asia: IFJ campaign highlights Kashmir’s ongoing internet controlsIndia: Kashmir unable to access COVID-19 information onlineIndia: Kashmiri journalist detained in nocturnal raidIndia: Kashmir police interrogate journalists for publishing banned outfit’s statementIndia: Despite Court order, government remains apathetic to restore internetIndian Journalists Union: Restore Internet access to Kashmir media

International Federation of Journalists,

Asia Pacific Office,

C/- Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance

245 Chalmers Street

Redfern, Sydney, NSW 2016, Australia.

Telephone: 61-29-333-0999

Tele fax: 61-29-333-0923

Quick Navigation

Partners Organizations

Opportunities

© 2025. SAMSN Digital Hub. All Rights Reserved. Site by: SoftNEP

- South Asia: Media unions and advocates calls for urgent end to Kashmir blockade